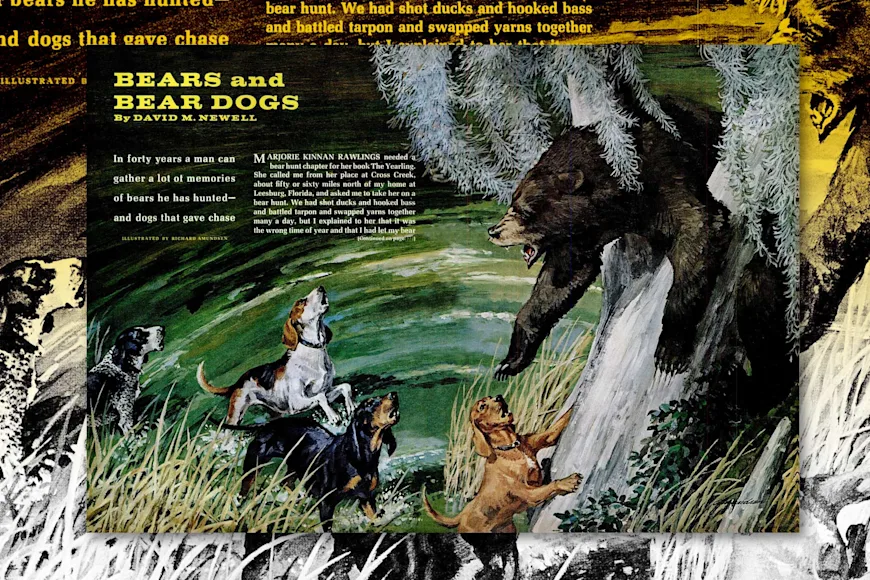

MARJORIE KINNAN RAWLINGS needed a bear hunt chapter for her book, The Yearling. She called me from her place at Cross Creek, about 50 or 60 miles north of my home at Leesburg, Florida, and asked me to take her on a bear hunt. We had shot ducks and hooked bass and battled tarpon

and swapped yarns together many a day, but I explained to her that it was the wrong time of year and that I had let my bear pack dwindle to three or four hounds and a couple of fighting dogs, which just wasn’t enough to hold up a big bear in these Florida swamps.

“But I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” I said. “You come down for a gamebird dinner next Tuesday night and I’ll take you on a bear hunt

.”

“Oh come now,” Marge said, “don’t give me any smart new version of the old snipe hunt gag. I just need some information and…”

“I’m serious,” I interrupted. “Come on down here and I’ll take you on a bear hunt that will make your hair stand straight up!”

“I’ll be there,” she said, “about 6 o’clock-but I’ll have to bring my baby brother.”

Well, this baby brother turned out to be 6 feet 3, very much of a man, and the dove-eating

champion of all the world. I can testify to this because with my own eyes I saw him down seven doves. I believe he ate one quail too, but he concentrated on the doves.

Afterward, we went in to the local theater where I had made arrangements to show a Paramount film I had recently completed with the old Grantland Rice Sportlight crew. It was called “The Aggravatin’ Bear,” and it was after seeing this film that Marge Rawlings wrote her chapter about “Old Slewfoot.”

As a matter of fact, she described my top fighting dog, Tough Bob, so perfectly that when N. C. Wyeth did the jacket design for her book, it could well have been a portrait of this white “catch dog.” A catch dog was a dog with a lot of bulldog or bull terrier blood—or both—and he was used in the old days to catch cattle and hogs. I had bought old Bob from a cattleman over near my bear-hunting camp on Blackwater Creek after the dog joined up with my hounds one morning and helped to make life so miserable for a big bear that it climbed to the top of a tall cypress.

“There ain’t no bear dares draw his button old Bob,” the boastful cattleman had told me. And he had been so right.

The Silver Grizzly

Of course, I couldn’t take my bear dogs to Alaska when Marjorie’s brother wired me to join him on a grizzly hunt a few weeks after he won the dove-eating championship, but I will say right here that things would have been different if I’d had old Bob and the rest of the pack along.

In addition to this bear-dog tale, the February 1970 issue included stories about steelhead, surf fishing, and sunglasses. The cover painting is by Mort Rosenfeld. Field & Stream

There was a silver-tipped grizzly

way up on the Unuk River, Art Kinnan told me when I transferred my duffle to his cruiser in Ketchikan. According to all reports, he said, it was a world record for size.

“The Johnson boys have seen him several times from their river boat,” Art explained, and they say his coat is something to see—dark chocolate with a silvery frosting.”

I’d like to be able to tell you that I’m sitting here now with my feet stretched out on a magnificent silver-tip grizzly rug, but such is not the case. I gambled my whole trip on getting that one particular bear, passing up a couple of others, but I never so much as laid eyes on that beautiful critter. Or at least not in the daylight.

Once he came up and chased the cook out of camp while I was up on the salmon stream watching for him. It was November and there was a late run of coho salmon in this little creek. I didn’t see the big bear but I sure heard him roaring his displeasure at our presence in his bailiwick the very first night we were in camp. Actually, I did see the shadowy bulk of him one morning in the gray mist just before dawn as we were wading up a stream, but my guide urged me not to risk a crippling shot in the dark and I took that advice—perhaps wisely, for I’m still around to write my observations on bears and bear hunting. But I’m sure that if old Tough Bob and his gang had been handy, they’d have rousted that grizzly out of those devil’s-club thickets.

I’ve been bear hunting off and on for over 40 years, in various and sundry places and with numerous methods of operation. Alaska brown bear and grizzly hunting can be tough or easy, depending a good deal on the size of your bank account. Please don’t misunderstand me. There used to be a time when I didn’t think I was hunting, really hunting, unless I was sleeping on a pile of rocks under a wet saddle blanket. No more. I’ll take all the comfort I can get-or can afford to pay for.

During a good many years of hunting in eastern Canada, I’ve killed quite a few deer but never a bear. As a matter of fact, I haven’t spent much time bear hunting in any of the Maritimes, partly because I don’t see very much sport in shooting a bear which is just coming out to get an apple for supper, though I suppose it would be breakfast for him, since he’s been asleep all day. So I don’t sit around anymore in old orchards in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, or Maine, straining my eyes in the gathering dusk. I’ll do this to lay low a fat young buck, because I’m very fond of venison, but I prefer my bear hunting with some action and excitement along with it.

There’s always been quite a hassle between Northern and Southern deer hunters in regard to the use of dogs, and the same thing holds true, more or less, for bear hunters. Which is more sport? To shoot an animal when it is unsuspecting or when it is roused and running with the hounds in hot pursuit. I’ve shot many a fine buck when it was standing or walking entirely without suspicion, and I’ve shot many a fine buck that was fanning the high palmettos ahead of the hounds. I must confess that there is much more satisfaction and excitement for me in the latter. I know both sides of the argument and each side has its merits. I am just expressing my personal preference.

Southwest or Bust

There are many places where still-hunting for bears is a pretty hopeless operation and where the use of dogs is almost a necessity. The rugged, brushy mountain country, for example, can be just as tough as a Florida swamp. Forty-three years ago, I went out to the northern Apache Indian Reservation to go to work as a predatory animal hunter for the old Biological Survey. I am sure of the date because recently Charlie Gilham stopped to visit me, and we were looking at an old scrapbook containing some of the government newsletters, which listed both of us as being on the honor roll for certain months—Gilham with wolves and coyotes and Newell with lions and bears.

When I left Florida in a homebuilt camper to go to work as a predatory animal hunter in Arizona, I took along nine hounds and two Airedales with which I had been doing quite a bit of bear business in the Florida scrubs and swamps. I couldn’t have been classed as a tenderfoot, but I was certainly a greenhorn in those Arizona mountains until I found out how to get around in the canyons and rimrock, and my dogs’ feet toughened up to the rugged, rocky terrain and they got used to working in snow.

Predator Control

When I reported to Mr. M.E. Musgrave at Phoenix, he gave me thorough instructions on my first assignment, which was the northern Apache Indian Reservation in the area of Fort Apache and Whiteriver.

“Now young man,” he said, “I know that you’re a bear hunter, but you’re out here on a job and not just for fun. I want you to go to Tom Wansley’s ranch, near the juncture of Black River and White River, and see what you can do about some lions that have been killing his stock, particularly colts. Make your headquarters there at the Five-PSlash, but remember that this is on the Apache Reservation and Mr. Charles L. Davis, the superintendent at Whiteriver, is in full charge of everything on the reservation, so I’d suggest that you check in with him right away and do whatever he tells you.”

There’s always been quite a hassle between Northern and Southern deer hunters in regard to the use of dogs, and the same thing holds true, more or less, for bear hunters. Which is more sport? To shoot an animal when it is unsuspecting or when it is roused and running with the hounds in hot pursuit.

Well, I went on up to the Indian Agency at Whiteriver and reported in to Mr. Davis. “Now, young man,” he told me, “the first thing I want you to do is get up there on Cedar Creek and give those stock-killing bears a fit. They’re killing cattle and I’ve been promising to send a man in there for a long time. I hear you’ve got some good bear dogs, so fly to it!”

“Yes sir,” I told him and headed for Cedar Creek.

The government hunters all had to make out complete reports on the predators they took, including stomach contents. If a man looked hard enough, he could find a little bit of beef in the belly of just about any bear. I know I did!

After we’d thinned out the bears a little, we moved back down to Wansley’s 5P/ ranch to see what we could do about the lions. Mountain lion hunting is, in my experience, about 90 percent trailing. A hunter and his hounds may spend all day or a couple of days cold-trailing a lion on its itinerary—particularly an old male which travels a big circle. A lion, being short-winded, doesn’t usually make a long run after he’s jumped and generally comes to bay in the rocks or goes up a tree after a short chase.

Bears sometimes tree quickly but very often will run and fight and run again, especially our bears in the South. We found that the western bears treed more readily, and this was also true of bobcats. We also found several color phases of the black bear in Arizona, something which I have never observed in the East. Our Florida bears are black and their cubs are black. We got one old cattle-killer in Arizona that was a rich cinnamon. My partner shot one “black” bear that was almost cream color, and I let a big one get away from me that was very large and a rich coppery color—just the color of a Duroc hog. A shell misfired and jammed in my rifle.

The western bears generally are chunkier in build than our Florida bears, which are usually rangier and longer-legged. This is not to say, however, that Florida black bears don’t reach great size. The largest we killed with my pack of dogs weighed 424 pounds, but they have been reported in the state at over 600.

Back in the late ’20s, I camped for some time in the Blackwater and Seminole swamp areas, near the little settlement of Cassia, lying near the St. Johns River in Lake County, Florida. There were a good many bears in this area then and there are some now. I was engaged in trying out many hounds for their courage and endurance, and I can’t imagine any tougher test of a dog’s qualities than running and fighting a big bear in the Florida scrubs, bay heads, and swamps. I had told Sasha Siemel, famous jaguar hunter in the Mato Grosso of Brazil, that I would bring six good tiger dogs with me from

It has always been amazing to me to see the varied reactions of dogs when they scent or see their first bear. Some big, rough, tough, swaggering, quarrelsome bully will tuck his tail between his legs and his hair will turn the wrong way at the first whiff of a bear. On the other hand, some shy, gentle little bitch will take a bear trail with the greatest enthusiasm and show unlimited courage when the bear comes to bay.

A Different Breed

Over the years, I’ve experimented with various breeds and strains of hounds and fighting dogs—Walker, July, and Trigg foxhounds; foxhound-bloodhound cross; wirecoated Welsh foxhounds from the famous pack of Erastus T. Tefft; red hounds from Virginia from the pack of Joseph B. Thomas, and some from Paul J. Rainey’s Mississippi hounds. I have owned Airedales and Kerry blue terriers that were too brave, and all kinds of dogs that were not brave enough! I have had mongrels and fox terriers and bulldogs and even tried some Norwegian elkhounds.

There is a strain of hounds in the North Carolina mountains, the Plott hounds, that have been bred for generations for hunting bears and boars in the mountain laurel thickets. The brindle markings on many of them indicate bulldog blood in their lineage, and they are courageous and tenacious. There are a lot of bear hunters in those mountains. I remember a gathering years ago at Dr. Ed Angel’s camp at Franklin, North Carolina. During the course of a very convivial evening, Ed asked me to draw him a picture on the wall of the camp, so I made a sketch of a Plott hound gnawing on the hind end of a big bear which was in high gear. The hound was hanging on and the fur was flying and the drawing apparently pleased a local hunter considerably (which wasn’t strange since his name was Crockett), because a few days later Dr. Angel phoned me over in Asheville, where I was spending the summer, and said:

“Dave, you’ll have to come over and draw that picture back again on my wall. That dern Crockett went there with a keyhole saw while I was at the hospital and sawed that whole picture out of my wall and took it home with him. I’ve had the wall refinished and repainted and you’ve got to come and draw it back like it was.” So I did.

Jaguar Dogs

After the weeding-out trials for the Brazilian expedition, which involved a lot of dogs and extended over months of really rugged work, during which we accounted for quite a few bears, I finally had decided on six dogs which I thought would make the grade in South America. Two were Thomas hounds; one was a Welsh hound; one was a very gentle, shy, little July bitch about a year old who was absolutely fearless, very fast and possessed of unlimited determination and endurance; and one was her brother, a dog with almost as many good qualities. Finally, there was Old Red. He was 9 years old and had been a wonderful deer dog all his life. The man who sold him to me said he thought he’d run a bear, if given a chance. This was a mild understatement. Old Red was in on the kill of eight bears and, after he got to Brazil, the first few jaguars. Then a 300-pound male jaguar got him. A dog can be cuffed by a bear and still make it, but if a big jaguar gets hold of him, it’s all over. Three more of the dogs were also killed by jaguars, but the Welsh hound and the July bitch survived the trip because of their speed and agility.

The man who sold [Old Red] to me said he thought he’d run a bear, if given a chance. This was a mild understatement. Old Red was in on the kill of eight bears and, after he got to Brazil, the first few jaguars. Then a 300-pound male jaguar got him. A dog can be cuffed by a bear and still make it, but if a big jaguar gets hold of him, it’s all over.

Along with the six dogs we took to Brazil from my Florida pack, there were six others from the Lee Brothers of Arizona, most of them trained, experienced cougar dogs. Even so, the big spotted cats of Mato Grosso took their toll. One of the dogs that weathered the entire year in the Brazilian jungles was Jake, although he lost one toe to a piranha (one of the blood-thirsty little fish found in the Rio Paraguay) and one pendulous ear which I had to amputate after it was badly mangled by a big jaguar. It made old Jake look a little lopsided but didn’t affect his hunting. He was 8 years old when we started for Brazil and, as I remember, had already been in at the kill of 46 lions, cougars, panthers, pumas—or whatever you choose to call the big tawny cats—as well as 18 bears, including two grizzlies. During the Brazilian expedition, he was in at the kill of 18 jaguars, plus numerous pumas and ocelots. ¡Que perro!

We brought old Jake back to the U.S.A. and I told of his exploits on a radio show in Madison Square Garden. He was bought by a sportsman who said he just wanted to give him a home the rest of his life and be able to say that he had owned the greatest big-game hound that ever lived. And I wouldn’t be surprised if this was true.

The “Rat” Pack

The Lee Brothers, from whom we originally got old Jake, have owned and trained literally hundreds of hounds, including many great bear hounds, one of which they sent me as a present. He was a magnificent animal, a big, rangy black-and-tan, with a tremendous voice—a deep bass bellow that would almost shake the needles off the pines. He was one-quarter bloodhound and showed it in the long ears and floppy jowls. His name, for some strange reason, was “Rat.” He was literally crazy about the scent of bear and would not run deer or bobcats. In the Florida scrubs and swamps where I hunted him there were no panthers, so when old Rat sang out you could bet it was a bear.

When Rat arrived from Arizona, I rested him two or three days and then took him over to Sulphur Island scrub on Blackwater Creek to see what he thought of our Florida bears. First crack out of the box we found where a big bear had crossed the sand road. The big hound took the trail in full cry, for it was very fresh. I had left my other dogs in my trailer and we had walked the sand road just to see what Rat would do. While my hunting companion went back to let the pack out of the trailer, I lit out through the scrub after Rat and the bear.

To my astonishment, Rat came back to me in a couple of minutes, stopped and looked at me, threw his head straight up and bellowed, then whirled and took the bear’s trail again for 50 yards or so, then came tearing back to me, stopping again with his ears cocked up and his head on one side, as if asking a question. He kept doing this and I couldn’t understand why in the world he didn’t stay with that smoking-hot bear trail.

It didn’t dawn on me until after the rest of the pack fell in, at which point Rat joined them, that all of his previous hunting had been done by men on horseback. Apparently, he figured on running the bear all right, but he was waiting for me to get my horse! I know of no other explanation for his actions, and when I wrote Ernest Lee about it, he seemed to feel that I had been right in my reasoning.

But regardless of why he hesitated at the start, the big hound really distinguished himself in the chase that followed. His tremendous voice echoed through Sulphur Creek Swamp above the cry of the pack and was something to hear. I have owned and trained 300 or more hounds in my lifetime and hunted behind some fine packs across the country, but this dog Rat had the greatest voice I ever heard—sort of a cross between Enrico Caruso and Feodor Chaliapin, if such were possible.

The Bear-Dog Chorus

The bear had fed out through the scrub during the night, breaking off branches of scrub oaks as thick as your arm to get the acorns, and was lying up in the high palmettos at the edge of Sulphur Creek where the pack rousted him from his bed, or “jumped” him, as we southern hunters say. There were 11 dogs in the race, eight hounds (including Rat), two “catch dogs,” and one scrubby, frizzly-faced little bitch that looked to be half wire-haired fox terrier. But she’d take hold of a bear and knew which end to go to. I don’t believe a bear could have laid a foot on her if they’d been shut up in a phone booth.

It was a frosty morning and the baying of the pack rang through the swamp—a sound that is music to a hunter’s ears. It’s exciting enough when the quarry is a fox, but when the hunter knows his dogs are driving a big bear, he gets an added charge. This was certainly true for me when I heard the pack swing toward the old tram road that crosses a narrow neck of Sulphur Creek Swamp, shortly before it joins with big Seminole Swamp. When a bear gets into the main swamp, the going becomes very rugged for dogs and hunters, and the bear can put up a running fight for hours in the boggy willow and saw grass ponds, refusing to tree and eventually whipping out the dogs.

All these things I had in mind when I got to my car and hurried as fast as possible in the heavy sand road back toward the narrow neck of swamp where I thought he would cross. I beat him there by about three minutes. He was perhaps a hundred yards ahead of the pack, and the dogs were running a breast-high scent, baying every breath. The whole works was coming just as straight to me as a martin to his gourd, and my hair was standing straight up and my mouth was dry.

When a big, heavy bear runs before the hounds, he “hassles,” or “belches,” as the swamp hunters say, and when I heard this and the crash of a dry palm fan, I flipped the safety off my .30/06 and held where I thought he would run across the old tram road. Well, I guessed right and knocked him down when he jumped into the open. I think that fixed everything in the mind of old Rat, who decided I must be a bear hunter after all—even if I didn’t have a horse.

_Read more F&S+

stories._