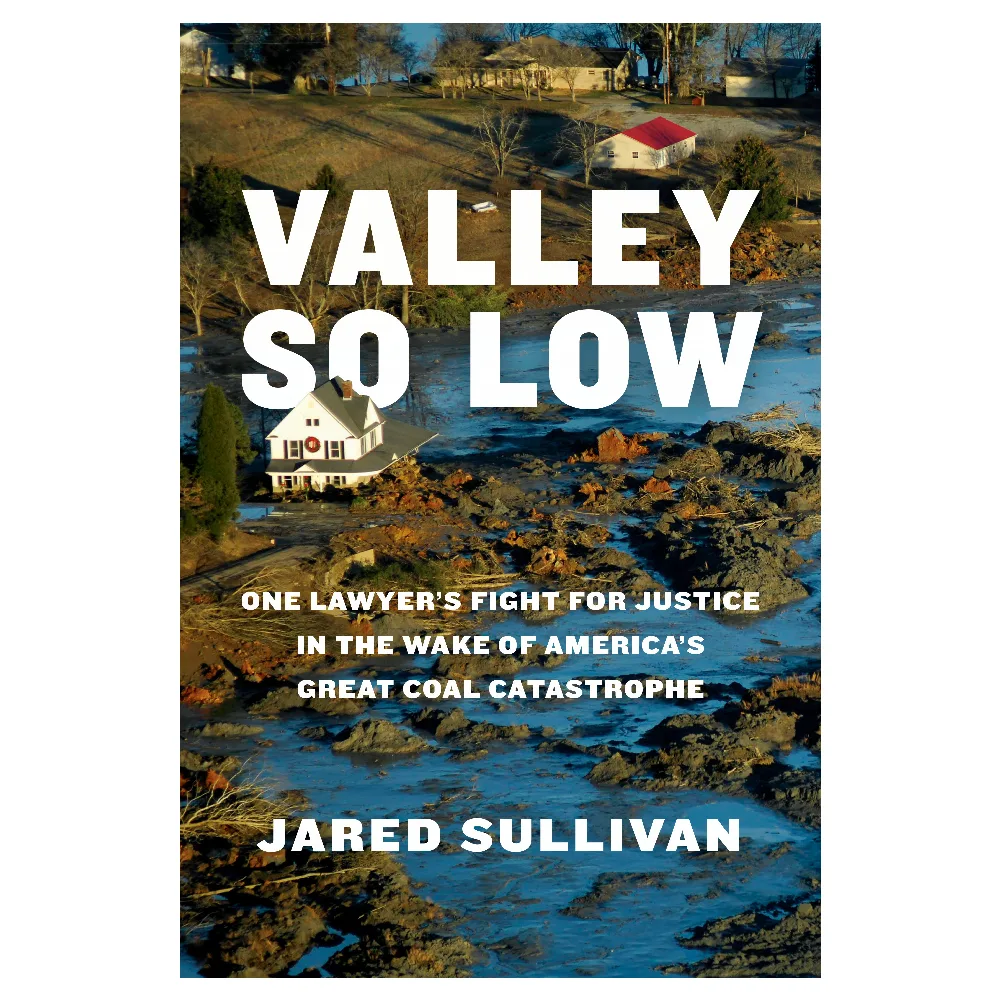

We don’t often cover books on F&S.com—but when we do, it’s about ones that we either love or ones written by an author we admire. Both of those criteria apply to Valley So Low: One Lawyer’s Fight for Justice in the Wake of America’s Great Coal Catastrophe.

Written by F&S contributor—and former F&S editor—Jared Sullivan, Valley So Low begins with a blockbuster reconstruction of a billion-gallon tidal wave of toxic coal-waste sludge that ripped through Kingston, Tennessee, in 2008, in what proved to be one of the largest environmental disasters in U.S. history. From there, the book tells the stories of the people who lost their homes, of the workers who fell gravely ill as a result of the cleanup effort, and of a local lawyer who agreed to take their cases in a legal battle against the Tennessee Valley Authority, a powerful federally owned utility.

I was lucky enough to get my hands on an early copy of Valley So Low this summer. Once I started it, I couldn’t put it down. This book is many things: a gripping disaster story; a David-vs-Goliath courtroom drama; and a conservationist’s call-to-action to protect our lands and waters.

Shortly after I finished the book, I called my pal and former coworker to chat with him about the writing of this book, its relevance to hunters and anglers, and what he hopes readers take away from the story.

CK: Congrats on the new book. How does it feel?

JS: Thank you. I’m super glad that it’s finished and that it’s out there. It consumed my life for years, and it’s been nice that readers have responded positively so far.

CK: You came to work at F&S full-time as an editor in 2015. Back then, when you were editing blog posts by David E. Petzal or Hal Herring or Phil Bourjaily, did you imagine that you’d be the author of a book one day? Was that something you aspired to?

JS: I came to Field & Stream because I wanted to do important work. But I was young—25 years old—so I didn’t know what I was doing. The job helped me earn my journalism chops, fast. I learned how to write clean, clear sentences by editing Petzal and Bourjaily. And later on, when I worked with Eddie Nickens, Bill Heavey, and Hal Herring, they really helped me understand storytelling—and helped me hone the tools I used when I eventually started writing my own longer pieces for Field & Stream, like a survival story about two fishermen off the coast of Texas or a feature about two lost hunters called “The Vanishing,” which I think is one of the better pieces I’ve written—

CK: It’s not just one of your better pieces, it’s one of the best pieces we’ve ever published, Jared. “The Vanishing” is a modern classic.

JS: Well, thank you. That assignment really opened up my universe, because it was the first time I spent months and months interviewing and building relationships with people in order to tell their story well. The story ran long—about 4,000 words—and after it was published, I was like, OK, I think I can write an even longer story now, if not a book.

CK: After your time at Field & Stream, you went to work at Men’s Journal. While you were there, you wrote a story about the coal-ash disaster in Tennessee—which then became the subject for your new book. How did this story appear on your radar?

JS: When I went to Men’s Journal, I was still the “outdoors guy,” so I kept a close eye on outdoor-environmental news, as well as news that was happening where I’m from in the South. I started reading daily newspaper reports about this trial that was happening in Knoxville. It seemed interesting—TVA was a cornerstone of the New Deal and is still a giant in the region—and, knowing that I’d be in Knoxville for Christmas break in 2018, I called one of the lawyers involved with the trial and asked what was going on. He told me there was going to be a ceremony at the coal-ash disaster site while I was in town, so I attended. There I met all these blue-collar workers, almost all of whom were sportsmen, and I realized that these were the exact kind of people I liked to write about—good, hardworking folks up against impossible odds. They were all incredibly compelling—but once I met the lawyers representing them, I thought, OK, now I actually have the full story. The article I eventually published about the coal-ash disaster and the trial for Men’s Journal ran at 7,000 words, which is very, very long—but I left so much material on the cutting-room floor. For example, there’s this catastrophic thing that happens to the lawyers’ office, and I didn’t even mention that in the magazine story. So, I knew there’d be enough material for a book.

CK: A lot of the characters in this book are described as people who love the outdoors. They’re hunters and anglers. Did your own background in the outdoors help you connect with them in your reporting?

JS: This book took me five years to write, and for the first two, I was living in New York City. So, even though I was raised in the South, near Nashville, when I flew to Tennessee to report and do interviews, some of the workers, understandably, still viewed me as this kid from New York. But I was able to quickly form a bond with them when I brought up that I hunt and fish and that I had worked at Field & Stream. People in the South don’t always have the most favorable view of the media. If you tell them you’re with The New Yorker, say, you might not always get a warm reception. But if you tell them you used to work at Field & Stream—and that you’ve fished the same streams they have—you’re usually going to be welcomed. I always was anyway.

CK: What’s next for you?

JS: Hopefully spending more time hunting and fishing. The Great Smoky Mountains are my escape. I had a full-time job while I was writing this book, so I was working nonstop—nights and weekends—for five years, while also trying to raise two little girls with my wife, Caroline. I didn’t hunt or fish much. Now I’m trying to make up for lost time. Maybe I can convince you to send me back to Alaska for Field & Stream.

CK: We can talk about Alaska offline. In the meantime, what do you hope readers take away from this book?

JS: That, as Americans, we’re better than this. These sorts of disasters—disasters that wreck a landscape and put toxins into our rivers—should not happen anywhere but especially not in this country. I’d like to think we’re better than this, as a people, and I’d encourage sportsmen to care about stuff like coal pollution, because it really does matter. I’m paraphrasing Hal Herring here, but these rivers and public wildernesses are our birthright as American citizens. We have to protect these places, because we can only mess them up once. That’s where environmental issues differ from policy issues. If you get a policy issue wrong, you can often go back and fix it. But with environmental issues, you only have one shot. And if you mess up that one shot at protecting a stream or wild place, it’s really hard to remediate it and make it as special as it once was.

This interview was edited and condensed for space and clarity.