Just hours into his second term, President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order called “Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential.” As its name implies, the directive aims to loosen wilderness protections that regulate mining, drilling, logging, and other forms of development on specific tracts of public land in the far-northern state. Specifically, it clears a path for controversial development projects like the Ambler Road (an industrial mining road proposed for the Brooks Range) and drilling activities in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). It also rescinds roadless protections from more than 9 million acres of rainforest in the Tongass National Forest of Southeast Alaska and expedites the construction of a road through a designated wilderness area in the Izembik National Wildlife Refuge.

A number of national conservation groups have expressed concern about Trump’s order in recent days—and the broad impacts it could have on hunting, fishing, and pristine wildlife habitat in the Last Frontier. Here’s what officials at Backcountry Hunters and Anglers (BHA), the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (TRCP), and Trout Unlimited (TU) are saying about the hunting and fishing grounds that would be affected by Trump's Executive Order.

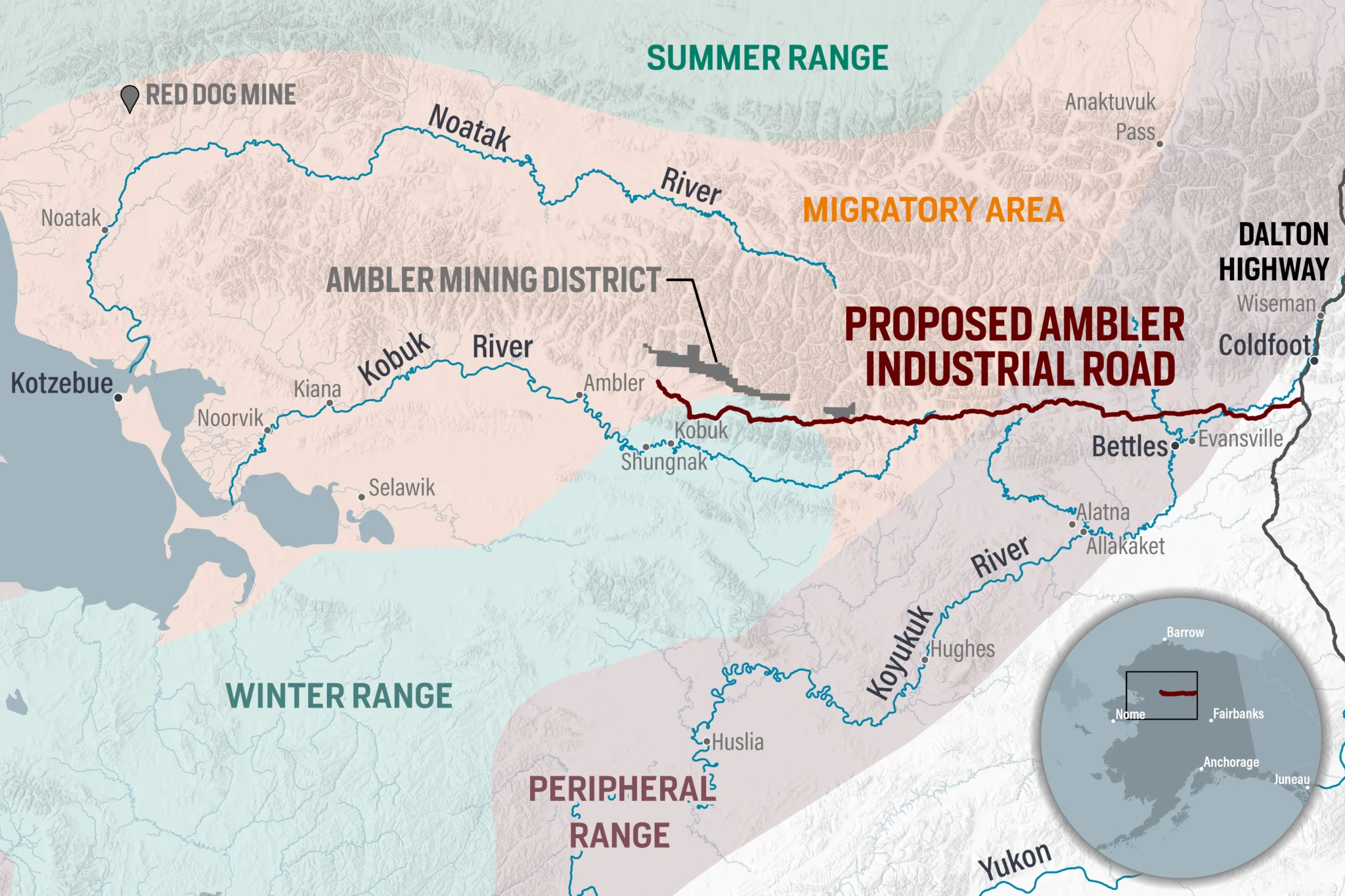

Ambler Road Reset

The Ambler Road is of particular concern to the TRCP. "The Brooks Range is one-of-a-kind," says the group's Chief Conservation Officer Joel Webster. "It's the wildest place left in North America. It really is a sportsmen's paradise."

The Bureau of Land Management denied a critical permit for the Ambler Road back in June 2024, a decision that the TRCP, BHA, and TU all applauded. In a statement issued at the time of its permit denial, the agency said that a completed Ambler Road would require 3,000 stream culverts while disrupting ancient caribou migration patterns. In the run-up to the BLM's permit denial, more than 14,000 hunters and anglers voiced opposition to the project, according to a coalition of outdoor non-profits and brands called Hunters and Anglers for the Brooks Range.

If constructed, the Ambler Road would be used by Canadian and Australian mining companies to extract copper and other minerals via large open pit mines in the foothills of the Brooks Range, north of the Kobuk River. It would stretch more than 200 miles and would be off limits to everyday travelers, according the BLM. Its course would stretch west from the Dalton Highway at the southern flanks of the Brooks Range to the south bank of the Ambler River.

The road would harm wildlife and compromise hunting and fishing in the Brooks Range and could also pose national security risks, according to Webster. "Given his American-first policy agenda, I believe the President would be concerned if he knew that the Ambler Road proposal was intended to support a foreign company that would mine and ship minerals directly to China," he says. "This landscape is incredibly important for its fish and wildlife resources. It not only provides local communities with subsistence hunting, but it’s an awesome place for fly-in adventures for people who want to go caribou hunting, moose hunting, sheep hunting, or fishing for Dolly Varden or sheefish." The Ambler Road, Webster says, would change that.

Roadless Rule Reversal

Nelli Williams lives in Anchorage and works as the Alaska Director for Trout Unlimited. She tells Field & Stream that TU is taking a hard look at a section in Trump's Executive Order that would remove Roadless Rule protections for the Tongass National Forest.

The Tongass is the largest national forest in the United States. At approximately 17 million acres, it makes up most of the land mass in Southeast Alaska. It is known for premier mountain goat, sitka blacktail, and black bear hunting, and it's one of the best salmon and steelhead fisheries in the country.

In 2001, 9.4 million acres within the Tongass were given special protections under the so-called Roadless Rule, barring the acreage from new road construction and large-scale timber harvest with some exceptions. Roadless Rule protections for the Tongass were widely supported by Alaskans then, and though the protections have been challenged, they remained in tact until 2019 when Trump exempted the Tongass from Roadless Rule protections.

The issue ping-ponged again in January 2023, when the Biden Administration fully restored Clinton-era Roadless Rule protections. But Trump's latest EO instructs his incoming USDA Secretary to overturn the Biden decision, putting the Tongass' Roadless Rule protections in limbo once again.

"Alaska's most abundant natural resources are our fish and wildlife," Williams says. "They contribute so much to the lives of people who live here. When I read through this executive order, I don't see the things that make Alaska special to so many of the people living here being reflected as a priority."

"The Tongass is a salmon powerhouse," she continued. "It produces more fish than all the other National Forests in the country combined, and lifting of these widely-supported roadless protections would compromise the spawning habitat that makes that possible."

In Southeast Alaska, thriving fisheries are an integral part of the local culture and economy, says Williams. "Twenty-five percent of the jobs in Southeast Alaska are in fishing and tourism; it's a $2 billion annual industry," she says. "That's why there was overwhelming public support for the keeping the Roadless Rule intact. It's a common-sense safeguard for the natural resources that people in Southeast Alaska depend on."

According to Williams, Tongass' current protections under an intact Roadless Rule don't completely prohibit all forms of logging, road building, or energy development. "As it currently stands, if a community wants to build a road or transportation corridor to access minerals or hydropower, the Forest Service has a process for reviewing those exceptions to the Roadless Rule," she says. "Almost all of them in the history of the Tongass have been approved, so local communities already have the flexibility to responsibly develop."

Trump's Executive Order won't immediately overturn Roadless Rule protections in the Tongass. Instead, it directs the incoming Secretary of Agriculture, who is still awaiting confirmation, to suspend the current Roadless Rule and implement the revised Trump-era version. "We don't know yet how this is going to shake out on the ground, Williams says. "But we're going to keep monitoring both the Tongass and the Ambler Road issue to make sure that the people who weighed in in support of these protections aren't ignored."

Re-Opening ANWR

Trumps Alaska EO devotes a lot of ink to oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). The vast wildlife refuge, managed by the United State Fish and Wildlife Service (USFW), has been a target for oil and gas development since it was set aside by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1960. It was opened to drilling for the first time in 2017 during Trump's first term. Then, in 2023, Biden put a temporary moratorium on drilling and canceled existing leases in the 1.4-million-acre coastal plain area of the refuge, which serves as a critical calving ground for Arctic caribou.

The day after Trump signed his Executive Order, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers issued a statement that strongly condemned the directive, and the re-opening of ANWR's Coastal Plain for oil and gas drilling and exploration was on the top of their long list of concerns.

"America’s Arctic is our largest expanse of intact public lands, and wilderness quality landscapes such as the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge represent the most treasured of these. Whether it's the pursuit of caribou, casting a line for Arctic grayling, or hunting waterfowl across the continent that nest in the Arctic during the summer, the value of this landscape for wide-ranging wildlife, and the hunters and anglers who enjoy them, cannot be understated," said BHA's Director of Policy and Government Relations Kaden McArthur in a separate statement shared with Field & Stream. "Coupled with the fact that interest in leasing in the Arctic Refuge is nearly non-existent as evidenced by not one, but two failed lease sales, it is abundantly clear that further attempts to develop this crown jewel of the national wildlife refuge system should be abandoned not doubled down on.”

Trump's EO vows to "rescind the cancellation of any leases within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and initiate additional leasing through the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program." According to McArthur, ANWR became the only unit in the National Wildlife Refuge System to require oil and gas leasing by law during Trump's first term. This sets "a terrible precedent for lands managed by USFWS, he says, which are typically managed to prioritize fish and wildlife conservation.

Course Correction?

Concerns about Trump's recent Executive Order aside, Webster says he's optimistic about working with the incoming administration to keep on conserving the special places in Alaska that are important to hunters and anglers across the country, particularly those in the Brooks Range along the proposed Ambler Road corridor.

He points to Trump's willingness during his first term to kill the controversial Pebble Mine gold-mining project (proposed for Bristol Bay) as proof that he might be willing to reverse course here—at least on Ambler. Trump reportedly denied permitting for Pebble at the urging of his son Donald Trump Jr., a well-known sportsman who says he hunts and fishes in Alaska frequently.

"We’re going to move forward and role up our sleeves and educate them on the importance of this place and the need to conserve it, and I think if the President knew that the minerals from this mine were going to China, he might have a different opinion," Webster says. "We had a good working relationship with them under the first term on issues like Bristol Bay and migration corridors and public access.

I see this as an opportunity for President Trump to cement his legacy as a champion of sportsmen and of special places by conserving the Brooks Range. To that end, we're here to work for him and his administration to benefit the interest of hunters and anglers."