_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

We’re both routinely asked: “Aren’t you offended when someone calls you a redneck?” And lately, we’ve gotten, “Will you have to schedule an apology tour once this book

is published?”

The answer to both questions is “no.” We aren’t planning apologies because we know what real rednecks are—male or female, knee-high or codger. You know them, too, if you’ve ever met them.

He’s the old man who can dig a lifeless outboard motor out of a junk pile and have it running in a few hours. Or the guy who can sight in his .22 with two shots, then go shoot a limit of squirrels—each behind the shoulder because the brains are the second-best part after the saddle. She’s the gal who figured out how to hook the disc to the tractor because no way in this world was she going to ask for help. Rednecks believe that a sucker, freshly gigged out of a cold Ozark stream, is the tastiest fish there is, and that a titty is the best way to quantify the size of a bream. For this book, we set out to capture the tips, advice, and hilarious stories from people just like that.

A redneck likes to look at life head-on, and so there’s a simple structure to this book. There’s hunting. There’s fishing. And there’s everything else. This is a selection of just a few of our favorite entries from The Total Redneck Manual

, some from each chapter. But if you really want to live large, you’ll need to buy the book.

Contents

Hunting

Fishing

Guns, Grub & Fun

Hunting

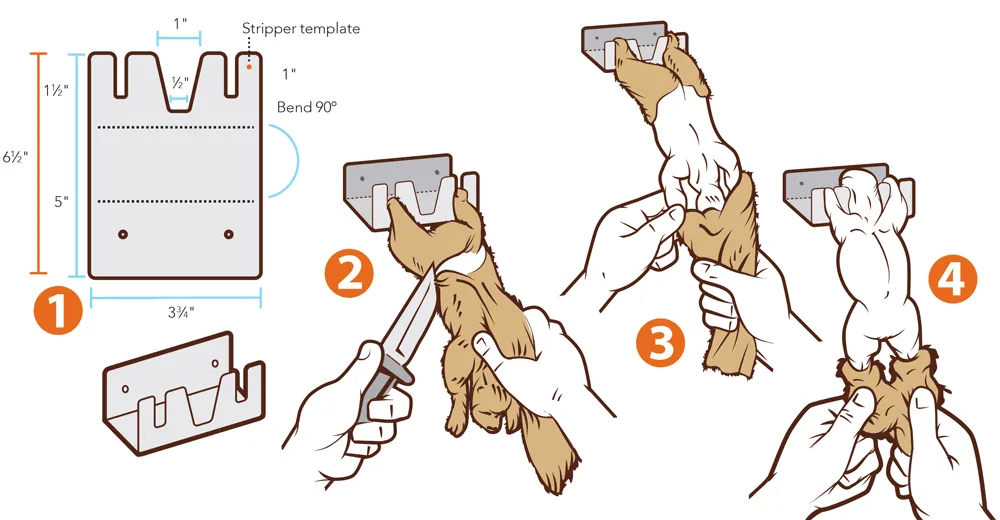

Make a Cajun Squirrel Skinner

How to make a Cajun Squirrel Skinner Raymond Larrett

Once you become a squirrel-killing machine and the critters start piling up, you might find that you want a more efficient way to process them. I witnessed this little trick device help my Cajun pals clean a washtub full of squirrels in no time flat.

Step 1The first step is to make the skinner, using the template shown here to cut and bend a 6 1 ⁄2×3 3 ⁄4-inch piece of 1 ⁄16-inch aluminum plate. Nail the squirrel skinner to a tree or post at shoulder height. Now you’re ready to rumble. Hook the squirrel’s rear legs in the two narrow slots with its back facing you.

Step 2Bend the tail over the squirrel’s back and make a cut between the butthole and the base of the tail, through the skin and tailbone. Extend this cut about an inch down the backbone and then down each side of the squirrel another inch, just in front of the thighs.

Step 3Next, grasp the tail and loosened hide, and pull down. The hide should shuck off inside out, except for a strip on the belly and the back legs.

Step 4Flip the squirrel over and place its neck in the wide slot and its front paws in the two narrow slots. Grasp the remaining hide and strip the “pants” off the squirrel.—T.E.N.

Hunt a 20-Acre Woods

Undetected stand access is the most important piece of hunting small properties. Russel Graves

Whether you’re trying to kill enough deer for the annual Baptist church venison feed or tag a big buck, consistent success on whitetails comes from a delicate balance of two variables: persistence and pressure management. You’ll never kill a buck from the couch (unless your couch is in a tree), but you probably won’t kill him if you hunt him too much, either. For most of the year, a whitetail’s home range is about 600 acres; a big buck’s core area can be as little as 50 acres. That’s why I’ll take three good 20-acre farms over one okay 100-acre farm every time. But the small farms have to be hunted carefully.

Scout ItLearning whether deer use the tract as a bedding or feeding area is the first step in deciding how to hunt it. In general, hunt food in the evenings and cover in mornings.

Use StealthThere’s nothing on 20 acres you can’t walk to, so learn how to access your stands undetected. That means staying hidden from deers’ eyes and their noses. I can get to one of my best north-wind stands in about five minutes by walking in from the main pull-off—but my scent will blow right into a bedding thicket on the way in. Instead, I circle around the farm, walk down a blacktop road, and then sneak up a deep ravine to my stand. It’s an extra 20 minutes of walking, but it’s worth every step.

Strike While It’s HotDon’t mistake “pressure management” for not hunting at all. If you’re seeing deer and not spooking them—especially during the rut—stay put. Food sources and patterns change, so you have to be in the tree at the best times.—W.B.

Master the Ground Swat

A ruffed grouse, prime for the frying pan. Shutterstock

Watching his high-dollar bird dog work an alder thicket, my Maine guide couldn’t help but laugh. “I didn’t know grouse could fly till I was 25 years old,” said Tim Winslow. “Everybody shot ’em on the ground, and nobody thought a thing about it.”

The ground swat is a hallowed tradition in many grousey corners of Redneck America. Some folks figure shooting a bird on the ground ranks down there with kicking kittens, but a lot of good people think it’s as natural as peeing off the back porch. I’d never shoot a bird from the truck, and I’d far rather shoot grouse on the wing. But after six hours of being a good boy that day in Maine, I got fed up with one pa’tridge in particular.

He ran through 80 yards of spruce hell without the good manners to flap a wing. I shot that sucker when he was about to squirm through another morass of dark timber, and I didn’t feel one bit dirty. It’s legal in most places, so if you’re up for the occasional ground sluice or limb level, make it clean. Check for dogs, other hunters, buildings, and endangered woodpeckers in harm’s way, then get you some groceries.—T.E.N.

Enjoy the Roast Beef of the Creek

Crockpot beaver tastes a lot like greasy roast beef, which is of course the best kind. Shutterstock

Late every winter, we begin to see deep pools of standing water in the creek bottoms on our farm. Dad will don rubber knee boots, grab a pickax along with his rifle, and then go wading through the mud with a purposefulness seldom seen the rest of the year. He’ll spend a day tearing out beaver dams and draining water, and then he’ll exhaust an evening shooting beavers as they attempt to repair the damage. “They’ll flood the whole damn bottoms if we don’t stop ’em,” he’ll say without fail.

For as long as I’ve been out of diapers, we’ve been fighting this battle with beavers and water and mud in our bottoms. I’ve often wondered if the beavers become frustrated when they find we’ve destroyed their dams, or if they relish the task of rebuilding. It seems to be the latter. My great-uncle Doug, who once used his track hoe to free a pickup truck that was hung up in one of the very mud holes to which I’m referring, dutifully noted that the drainage would continue to be an issue in our bottoms because “it will always be low ground.”

Truth is, Dad would be distraught if not for the beavers and the mud. As he’s gotten older, he’s been trapping them more often than shooting them, and, on several occasions, he’s celebrated his short-lived victories by skinning and cooking the beavers. Seared beaver tail is full of rich fat, and it’s supposedly an haute cuisine delicacy. I’ve not tried it. But I do know boneless beaver meat, cooked in a Crock-Pot with gravy and vegetables, tastes a lot like greasy roast beef. Which, of course, is the best kind. Fortunately for us, there seems to be a never-ending supply of it.—W.B.

Work for Your Ducks

Duck hunting: where you can break a sweat, standing in the water, on a 20-degree morning. Russell Graves

We had to cross the river to get to the pothole where the teal and mallards crowded onto a 4-inch-deep puddle inaccessible by boat. But first, my buddy Lee Davis and I had to hump our mess of gear down three-quarters of a mile of railroad track and tightrope-walk across 200 yards of dark trestle. The only good thing about it was that there wasn’t any hurry.

We’d started out earlier than planned. The evening before, we’d stuck the truck in the mud while scouting for ducks, so Lee called his wife to come pick us up. Thing is, we dug the wheels out before she got there. We passed Anne going in the opposite direction, and the look on her face through the driver’s side window told us that heading back to the Davis house right away might not be the wise move. So we headed on down to the river and started walking.

That was with two dozen decoys on our backs, waders slung around our necks, and each of us carrying the inner tube from a dump-truck tire. We remembered the boat paddle halfway across the trestle but were too far gone by then to turn around. We sat in the tubes and used a stick to paddle ourselves across the river, which took a while. But, as it turned out, if we hadn’t gotten stuck in the mud the night before, and pissed off Lee’s wife, and left early for the river, we never would’ve made it to the ducks by shooting light. God looks out for fools and rednecks.

And he must have a particularly soft spot for good old boys just barely getting by. During college, my mode of transportation was a 1973 two-door Mercury Capri I’d bought for $300, which was all the money I had in the world. Not exactly a redneck ride, but I made do. During trapping season, I hauled beaver traps in the back seat and beaver carcasses in the trunk. During duck season we stuffed that $300 clunker with decoys and waders, laid the quilt my aunt made me as a college send-off gift across the roof, and lashed the canoe down with rope that we ran through both front windows. Once the boat was snugged down, the only way in or out of the car was through the windows, Dukes of Hazzard–style.

Our favorite spot was a marshy lake finger we dubbed Pinto Point, in honor of my buddy Jake Parrot’s favorite duck-blind breakfast: a Thermos full of pinto beans, onions, and hot sauce that produced more dirty energy than a mountaintop coal mine. We had to drag the canoe in from the hardtop because there wasn’t enough ground clearance in a fully packed Capri to make it down the dirt road. We had a single duck call between us—a Sure-Shot Yentzen—and no dog. We retrieved ducks with a fishing rod equipped with a Jitterbug. The one time the treble hooks failed to snag a downed bird, Jake swam out in his underwear to make the retrieve. It was January. The duck was a banded drake canvasback. It’s on my wall today, more than 30 years later, and it’s my favorite mounted critter of all time. That’s because we got after them back then, made do with what we had, and worried less about charging the decoy batteries than calculating how many layers of waffle-weave cotton long johns it would take to keep a kid alive. Especially if you had to swim for the birds.—T.E.N.

Fishing

Shop Local

The old woman behind the bait shop counter always knows where the bream are biting. Shutterstock

You can ask Mr. Google about fishing all you want, but he knows squat compared to the fine folks manning the Nabs rack at your local bait shop. That’s how I wound up with a dozen sickly looking wet flies the locals around Fargo, Georgia called “sallies,” which I was told was all I needed to load my boat with Okefenokee Swamp fliers.

Nabs Man directed me to a rack of the flies, all locally tied. They came two to a pack and were displayed on a tall wire rack that I’d bet held potato chips once the fishing slowed down. Had I been merely browsing on my own, I wouldn’t have looked at them twice. Instead, I bought two dozen and fished them like the man said: on light line, under a light bobber, as close to stumps and swamp slop as I could get them.

I didn’t sink the boat with fliers, but I caught them right and left, plus warmouths and even a bowfin, and fished til the sun started setting and the alligators got a little too close for comfort. It was a lesson everybody needs to relearn now and then. Don’t ever drive by the bait shop that’s right there at the boat ramp. There’s a Nabs Man in most every one, and while Mr. Google can get you to the water, Nabs Man will get you into fish. —T.E.N.

Learn Some Wrasslin’ Moves

I’ve seen 12-year-olds who wouldn’t watch a bobber for 5 minutes take to grabbing catfish as if it were the secret to an eternal summer break. You don’t have to be a bodybuilder to do this, either. Physical strength doesn’t hurt, but proper technique, a love of being in the water, and a taste for some mild violence are all far more important when you’re wrestling catfish.

Catfish fight with their heads and tails. Subdue both ends and you can often noodle a flathead without suffering more than a scratch or two. If the tail gets away from you, the fish will peel the skin off your arm all the way to the boat. If you let go of the head, you’ll have to explain to your buddies why you lost the fish, which is worse than any physical harm you might endure.

How to noodle a flathead catfish, step by step. Conor Buckley

Step 1When you get a fish, grab its lower jaw and pin the fish to the bottom, to keep it from rolling.

Step 2Slip your other hand underneath the gill plate, being careful not to damage the gills.

Step 3Ease the fish out of the hole and pull its chin tight against your chest.

Step 4As the tail comes out of the hole, wrap your knees around the fish’s midsection and cross your ankles. Its tail will fan between your calves—far better than thrashing your arm in open water.

Step 5Have a buddy pull you to the bank or boat, and break out the stringer.—W.B.

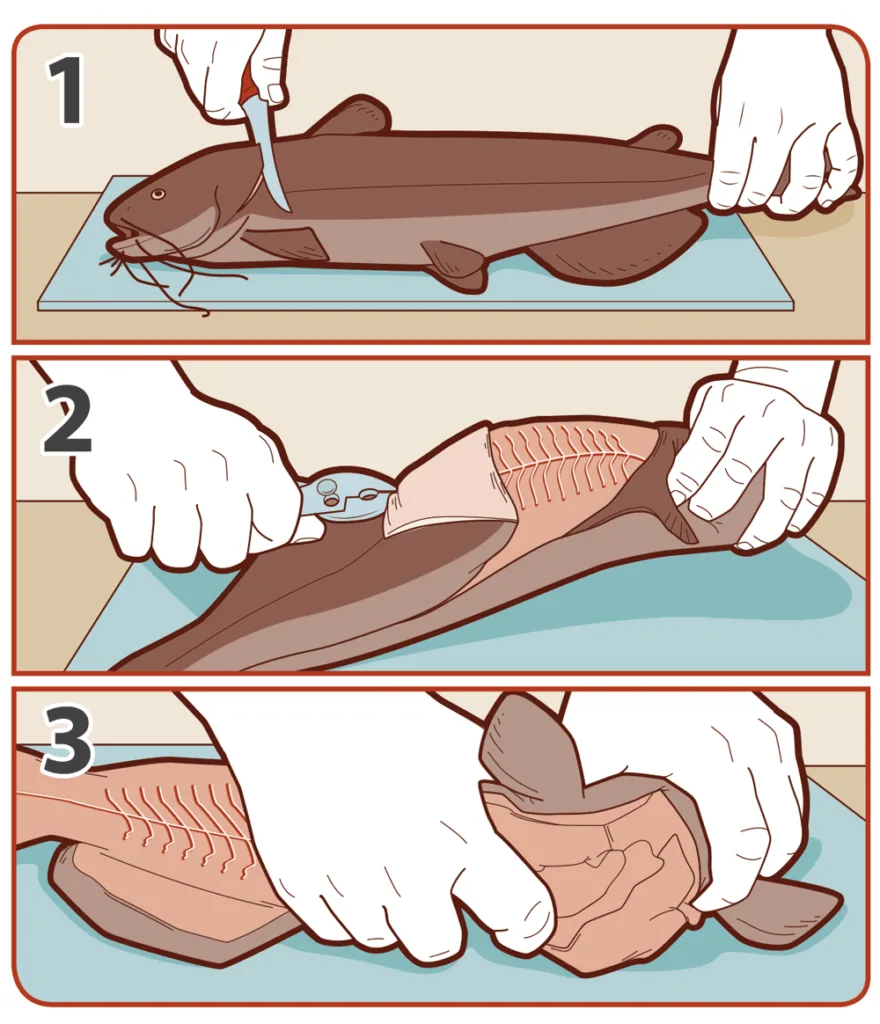

Hell, I Can Skin That!

How to skin a channel catfish. Vic Kulihin

Your garage or tool shed should hold everything you need to skin a catfish. If it doesn’t, you need to quit cleaning it out so often. Start with a 3-foot length of 2×6, untreated if possible. Place the board on a level, waist-high surface—such as a truck tailgate— and get cracking.

Step 1Use a sharp knife to score the skin around the head in front of the gill plates. Make another slit down the back to the tail. Drive a nail through the fish’s skull and into the board. Cut off the dorsal fin.

Step 2Brace the board against your waist with the fish’s tail near your body. Grasp the skin with pliers and peel it back toward the tail. The skin may come off whole or in several strips.

Step 3Remove the fish from the board, grasp the head in one hand and the body in the other, and bend the head down sharply to break the spine. Bend the body up and twist to separate the head from the body. Most of the guts will come out with the head, but be sure to split the belly open and clean out any that remain inside.

Serve Fish a Casserole

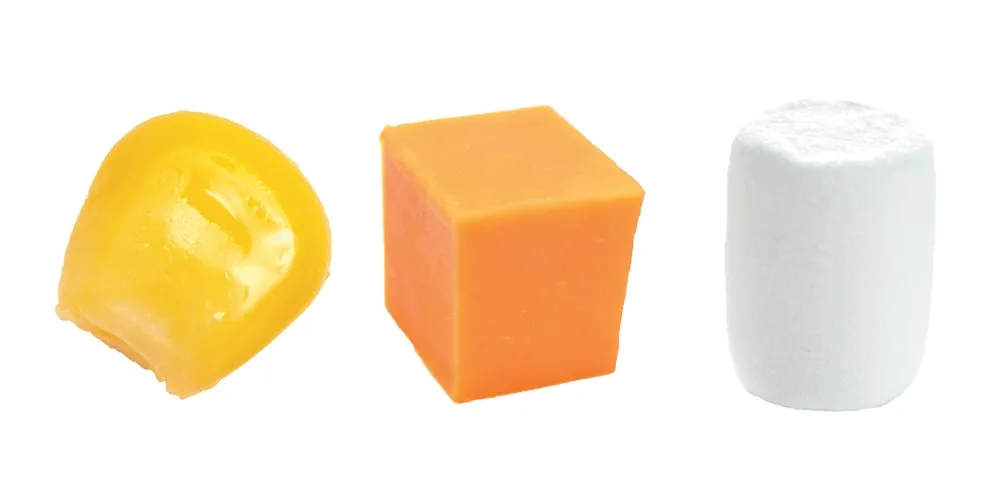

The Holy Trinity of redneck side dishes and trout baits alike. Shutterstock

Behold, the Holy Trinity of redneck side dishes and trout baits alike: corn, cheese, and itty-bitty marshmallows. Talking them up to anyone who puts on airs might get you chased out of your local Trout Unlimited chapter, but, by golly, this trio of grocery store staples will stack up the trout.

CornFresh off-the-cob corn won’t cut it nearly as well as whole kernels from the scratch- and-dent bins over near the pork scrapple. Maybe it’s because hatchery trout chow contains corn, maybe it’s because a corn kernel is about the size of a trout pellet, or maybe it’s because corn looks like a trout egg. But newly stocked trout will whack corn above anything else. Juice your bait with a salt-and-garlic bath overnight.

CheeseNothing works like store-bought Velveeta. It can wash off the hook, though, so keep the block in a cooler until you’re hunk for bait. Push the eye of a treble hook through a ball of the cheese until it’s on the shaft. It’ll seat down on the hook with the force of your cast. If you want to get complex, melt Velveeta in a pan and add garlic, salt, cornmeal, and bread crumbs, and it’ll hug the hook tighter.

MarshmallowsTiny ones like those you sprinkle into hot chocolate seem to turn stocked trout inside out. Like corn, it could be that they resemble trout pellets or fish eggs, but they’ll load up a stringer in a hurry. One bonus for fishing marshmallows is that they float, and even trout that aren’t above eating Velveeta, corn, and marshmallows don’t want to dig a meal out of the muck.

Trout Fishing with Kenny Dean

Trout fishing with Kenny Dean on the White River in Arkansas. Shutterstock

On my first morning in Calico Rock, Arkansas, I awoke to the sight of Kenny Dean sitting on the toilet. The door to the bathroom worked just fine, but it was like the thought of a constitutional without an audience never occurred to Kenny. He was beaming from ear to ear and yelling at my dad, who was still asleep. “Jimmy! Jimmy, get up! We have to get this boy out there to go fishing,” he said. “He’s going to catch a big brown today, I just know it.”

At 14 years, I didn’t need any extra coaxing to get up and get dressed. The room smelled like wet waders, outboard gas, and whole-kernel corn from the previous evening’s foray. I’d already caught my fill of the ’bows; what I wanted was a five-pound brown trout for the wall. I retied the crankbait—a Rapala CountDown Minnow—that I’d been casting the evening before. Kenny said it would work as well as anything to catch a big trout, and when it came to fishing, I trusted him over anyone else.

Kenny was a lawyer (a good one, Dad said) but he kept a boat hitched up to his car, even parked at the courthouse. I mainly thought of him as a professional fisherman of sorts, since we hadn’t had that many interactions that didn’t involve fishing. He grew up in Arkansas, so he was the perfect guide for a White River trip.

We hit the river that day with half a dozen spinning rods rigged with crankbaits and corn spinners, along with Dad’s fly rod, which mostly remained on the floor of the boat. Kenny brought several cans of Beanee Weenee too, because he was prone to low blood sugar, and Beanee Weenee was the surest of all cures for that. It was 90 degrees by noon, when Dad tied up the boat in the shade of a river bend to eat lunch. The White’s modest current kept the boat swaying gently against the tether. Kenny leaned back in his seat and sang. “Under the shade of the beech nut tree, little Will Brantley there sat. He was amusing himself by…”

“Kenny!” Dad interrupted. “Don’t you teach him that song.”

Kenny just smiled. Five minutes later, he whispered the remainder of the tune in my ear. It was the filthiest thing I’d ever heard.

Later that night, the room again smelled like wet waders and trout slime. Dad and Kenny were kicked back on the motel beds, sipping whiskey from the same stainless Thermos lids they’d used as coffee cups that morning and tobacco spitters at midday. Exhausted from the casting and the sun, I turned on the sink to brush my teeth, took in a mouthful of water, and immediately spat it out.

“Ugh! This water tastes awful!” I said. “Dad, I’m gonna have to rinse my mouth out with some of your whiskey.”

Kenny belted out his signature rapid chuckle. “You hear what he said, Jimmy?” “Yes,” Dad said, fighting back his own smile. “I heard it.”

It was a good detail shared at just the right time. And with it I’d earned my right to stand there and laugh with the men. —W.B.

Guns, Grub & Fun

Teach a Kid the 7 Farts

Once a kid’s ready to catch a snake, he’s probably ready to master the seven types of flatulence. Shutterstock

For his twelfth birthday, my younger brother, Matt, asked to go bluegill fishing with my dad and Kenny Dean. Kenny was a lawyer, originally from Arkansas, who mostly specialized in fishing, duck hunting, dirty jokes, and whiskey. When I was young, he nearly convinced me that he was my real daddy, and he was always singing these short little songs about some lady from Nantucket.

Matt’s birthday weekend was a success. They camped, and he came home with grand tales of bluegills and little bass they’d fried over a fire and eaten with white

Our mother was thrilled with the lesson. Like a cherished recipe, it was passed on verbally through the generations, Matt and I have taught the seven farts to half a dozen or more youngsters worthy of such knowledge, usually while fishing or on opening morning of deer season. I know that my boy already gets a big kick out of flatulence, and so I expect him to have the full seven committed to memory by kindergarten. —W.B.

Teach a Kid to Drive a Stick

Teaching a kid to drive a manual transmission is easy … you can drive one, right? Shutterstock

Only about 5 percent of today’s new vehicles come with a manual transmission, so it would seem that teaching a kid to drive a stick would be an obsolete skill. It’s not.

Let’s say your boy knocks on his prom date’s door and shakes her dad’s hand. “She’s getting ready, son,” he says. “How would like to escort my princess to prom in my old Vette?”

Your son can fumble around, Googling “how to drive a straight shift” on his phone before conceding, “No, I’ll stick to my mom’s van.”

Or he can say, “Thank you, sir,” before jumping into the driver’s seat and burning through all six gears before they get to the end of the street. The old man might be left wondering which room in his house will be his new grandchild’s—but he’ll be impressed nonetheless.

Knowing how to drive a stick is critical to the self-reliant redneck lifestyle. Just teach using something old that won’t be ruined by a few dents (I learned on an ’80s model Toyota 4-Runner that I drove straight into a tree. I was 12).

Start on a very slight downhill slope, preferably on a gravel back road with minimal traffic, where the kid has the best chance to get the vehicle going. Have the engine running, gear in neutral, and parking brake set. Adjust the seat properly for your kid’s legs. Let them get the feel of the clutch a few times before shifting to first gear. Have your kid slowly release the clutch and, just as the vehicle begins to move, give it just a bit of gas. The engine will die a few times, but laughing at that is just a part of the process.

Once the kid masters getting the vehicle going from a stop, teach him or her how to move through a couple gears—but you shouldn’t go much over 30 miles per hour. The kid should master the feel of the clutch and getting the vehicle to start and stop without dying before gaining much speed—especially before moving on to the blacktop.

You can drive a stick, right? This should be easy. —W.B.

Pick a Tick

If you’re picking a tick, be sure to remove the whole vile critter. Shutterstock

Hank or George. Dale or Jimmie. There’s a lot we might argue over but this much is gospel: Ticks are nasty. They’re nasty when they’re creepy- crawling under your Fruit of the Looms; they’re nasty when they’ve latched onto the tender tippy-top of your butt crack; and they’re for durn sure nasty when they’ve blown up to the size of a grape and are sticking out of your dog’s ear at 2,000,000 PSI and you’re going in with a thumb and forefinger.

Growing up, we knew exactly what to do when we got tick bit: We smeared Vaseline on the ticks to suffocate the little S.O.B.s, or we burned their butts with the tip of a hot match because somebody said that would make them back right out. Now we know that all that did was make them vomit more tick goo into our bloodstream.

In these more enlightened, Lyme-ridden days, doctors advise none of the above. Nor do they advise just sucking it up and snatching the ticks off with your fingers. Instead, we are admonished to clean the area around the tick, place the tips of tweezers firmly against the skin, close the tweezers around the tick’s mouth, and pull it out. After which, of course, we are advised to clean with rubbing alcohol and first-aid cream, which I never have, and save the tick in a plastic baggie for later identification, which I would never do.

But I have used small fishing pliers and fly-fishing forceps in a pinch. And I’ve even used light monofilament: Bend it a U shape, slip it over the tick, push it down around the mouth, bend the tick over backwards, and yank like you’re pulling out a tooth. This method isn’t AMA-approved, but most of the time it will jerk a tick out clean as a whistle. —T.E.N.

Stock a Redneck Mama’s Toolkit

Know the must-have items in a redneck mama’s toolkit. Shutterstock

Let us celebrate Mama, the most sacred redneck of them all. From cooking dinner to fixing what’s broken to administering discipline (all three of which are frequently done at once), every Mama needs a tool kit. Here’s a look at some of the crucial items.

Squeeze Butter: It’ll grease a skillet and spread easily across biscuits. Kids love the farting noises that it makes when near empty.

Hamburger Helper: Pair it with any ground meat—from venison to beef to goat—for a quick and nourishing meal.

Fly Swatter: Makes unruly toddlers and coon dogs listen every time.

Cool Whip Tubs: Redneck mamas might accept Tupperware at Christmas, but her cabinets are full of these.

Boxed White Zinfandel: Mama’s medicine at the end of a tough day of raisin’.

Folding Camp Chairs: Whether the family’s coming over, a ball game’s on the schedule, or Mama just needs a quiet moment to herself in the yard, camp chairs will deliver.

Muti-Tool: Mama might need to open a can of beans, change a clothes dryer fuse, and assemble a Power Wheels Jeep all in the same day. With this, she can.

Yoga Pants: Not for working out—for the fact they always fit no matter what. Plus, they nicely display that tattoo she just paid off.

Cigarette Purse: Even if Mama gave up the menthols, she still carries her phone, credit cards, and .380 auto in this.

Wire Coat Hangers: From triple layering her “winter stuff” to unclogging sink drains, wire hangers do jobs in ways plastic hangers simply cannot.

Paint Your Truck Camo

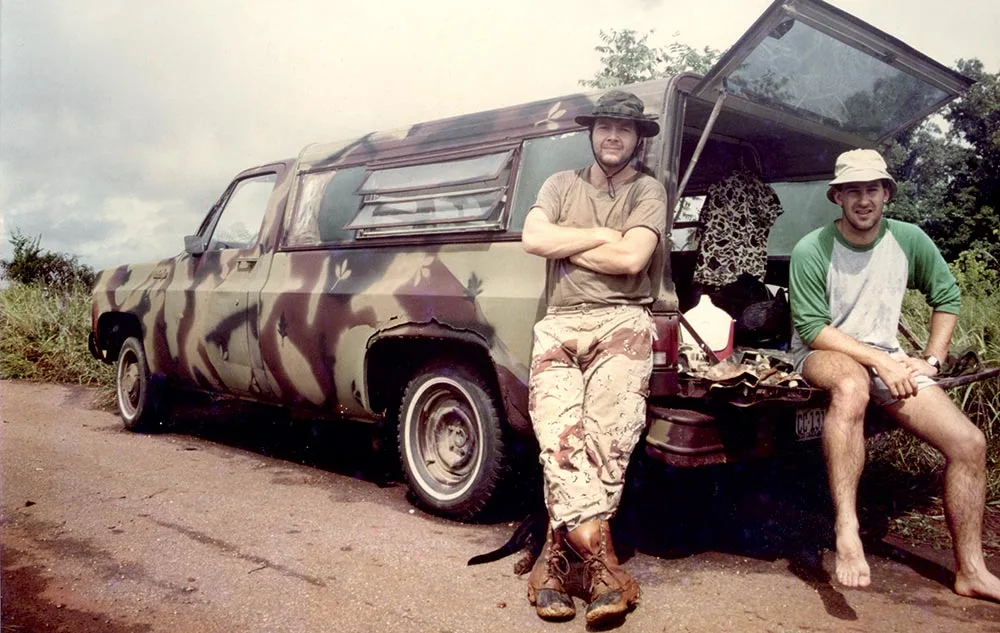

Nickens, his buddy, and their spray-painted chariot. T. Edwards Nickens

We’d hunted that morning, and were wore out from a long walk out of the beaver swamp. Sitting on my duplex porch listening to the truck engine tick and hiss, we hadn’t given a single thought to what we were going to do with the next 8 hours of daylight. That’s a luxury you have when you’re in your 20s, working a pretty good job, and you haven’t yet fallen under the spell of the wedding preacher. I think this was during the short October wood duck season, but I’m not sure. Can’t recall if we killed any ducks that morning or not, nor where we hunted. But I very well remember the moment my buddy Lee Davis set down his spit cup and spoke a word of prophecy.

“One of these days,” Lee reckoned, “we ought to paint that truck camo.”

I sat bolt upright in the straight-back rocker. There are moments in life that flash like lightning, and you know you should act fast before you think too hard. This was one of them.

“Let’s do it,” I replied. We were at the hardware store in less than 5 minutes.

That was my first pickup. I’d paid $500 for it when $500 could get me through a month. My mom brokered the deal with a guy on the construction site where she worked as secretary. The rig was a white 1973 Chevrolet Silverado with a long bed, beat-up camper shell, and 3-on-the-tree transmission. Corrosion had eaten the fender wells, and some spots on the floor were so rusted out you could you see the road under your feet. But she started every time, got pretty good mud traction with the shell’s weight, and she was all mine.

“What you painting?” asked the clerk at the register when I asked where they kept the spray paint. I suspect he figured I was working on some respectable project, like an iron fence or outdoor table.

“That truck right there,” I told him, nodding through the storefront glass. He jerked his thumb towards the back of the store and excused himself. Lee and I just about cleared the place out of Rustoleum in the four colors of the redneck rainbow: green, brown, black, and primer.

Ninety minutes later, we were done. We hadn’t had a plan or a pattern, though Lee cut some leaf stencils out of a cardboard box that turned out pretty nice. Most importantly, we didn’t have anybody looking over our shoulders and sniffing, “Y’all ought not do that.”

Everybody loved that camo pickup truck, except maybe the neighbors. People would honk and wave, folks would turn their heads on the sidewalks, and I could hear what they all were thinking: “Dang. I wish I had a camo truck.”

Julie and I were dating pretty heavy by then, so I knew she wouldn’t just break it off outright. But that truck was my sole transportation, and she didn’t fully buy into the awesomeness of a 15-year-old pickup in DIY Realtree. But she had her own sweet ride, an Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme coupe with a 3-speed manual that would bark tread like a beagle pack, so it was something to drive on dates until I got a red S-10 Blazer with power windows and everything. Marriage followed closely, so you know where this is going.

I don’t have many regrets, but selling that truck is high on the list. A tatted-up bricklayer bought it for $350. But for a few glorious years that truck embodied a certain approach to this business of life: Anything worth doing is worth doing right now before somebody hears about it and ruins your moment of inspiration.

And don’t ever let anyone ever tell you “primer” isn’t a color. —T.E.N.