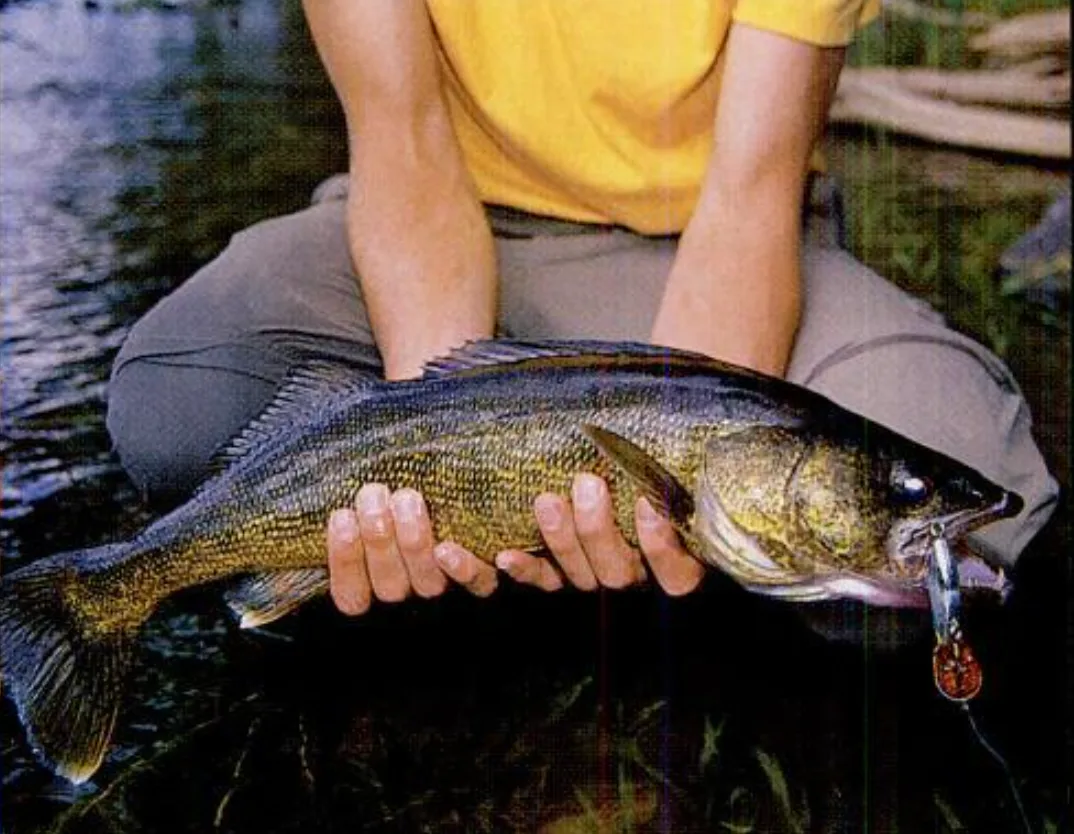

I catch the first fish at Deadwood Portage. It’s a nice 3-pounder that takes a curly-tailed jig bounced through a short, rocky rapid. The walleye flashes its signature gold-green flanks. Dinner fish, I think and thread it on a blue nylon stringer: metal tip through the bottom of the lip, then through the O-ring to snug it down. For just a moment I wonder about the satisfying act of putting a fish on a stringer. How many times have I done this without a single second of reflection about how fortunate I am to be able to catch, clean, cook, and eat my own fish? I slip the stringer into the water and the introspection goes down with it.

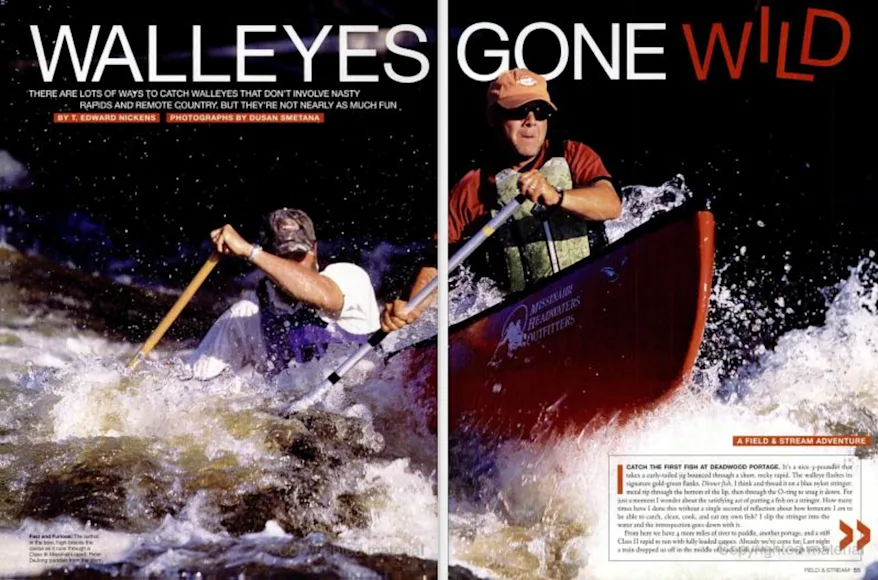

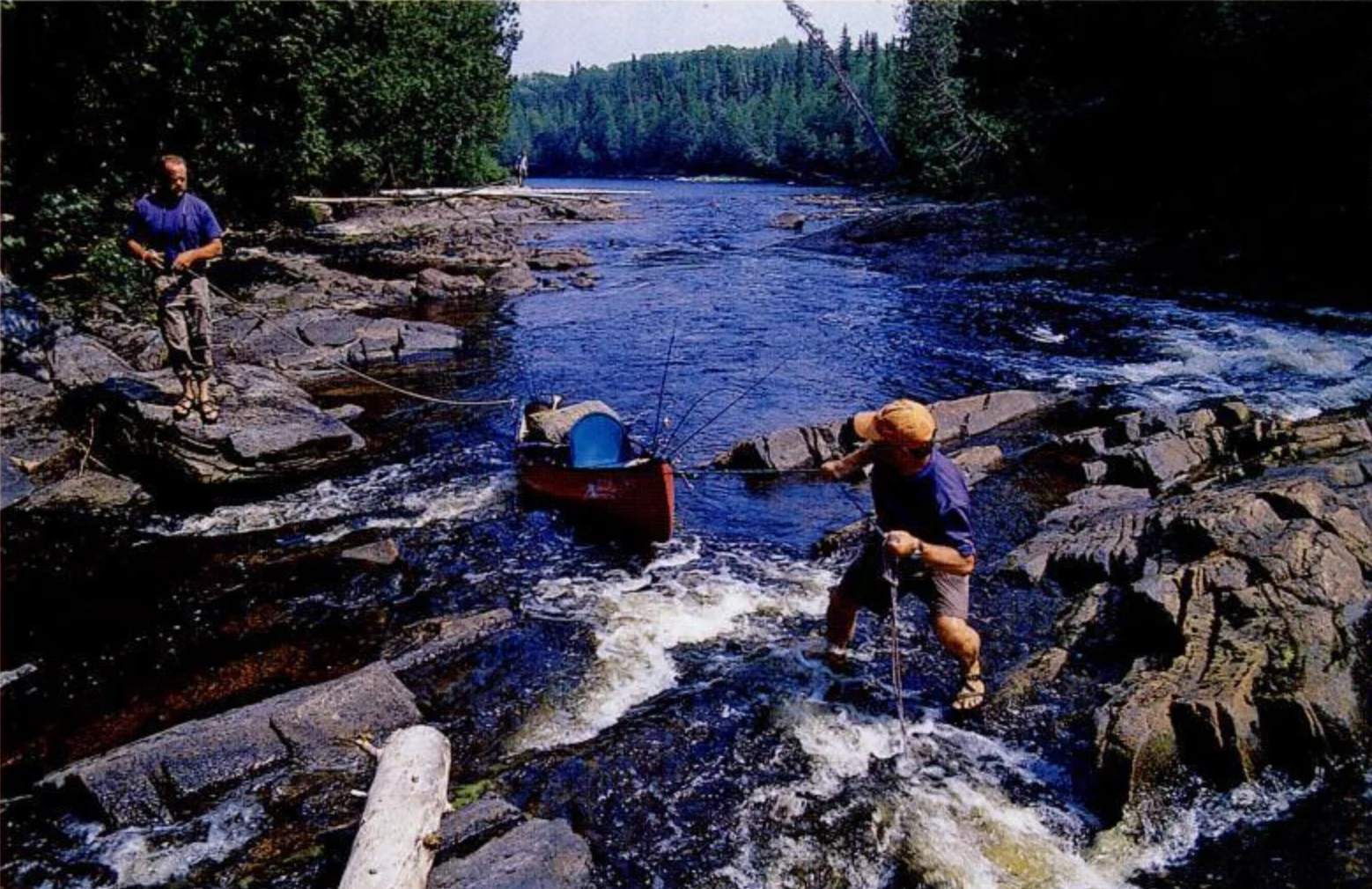

The adventurers line their canoes through a rapid. Dusan Smetana

From here we have 4 more miles of river to paddle, another portage, and a stiff Class II rapid to run with fully loaded canoes. Already we’ve come far: Last night a train dropped us off in the middle of black-dark nowhere for a rough bivvy by the Canadian National Railway tracks. We slept off a 20-hour travel day until midmorning, then pushed the boats through Peterbell Marsh to the Missinaibi River, a languid, amber-colored waterway hemmed in with spiky grasses. Bleary-eyed and saddle sore before our first canoe stroke, we paddled north. Now we have more paddling ahead of us, wood to gather, a fire to build, fish to fry, and tents to pitch, and the sun is dropping fast. So far, I’m getting exactly what I’d hoped for.

River Runners

When most people think of walleye fishing, they think of big lakes, big outboards, downriggers, lead-core trolling lines, and crankbaits running so deep the fish need eyeballs the size of gumdrops.

But we had a different idea. My friend Peter DeJong and I knew that not all walleyes hang out in white-capped lakes. We figured there were wilderness fish far up in the northlands, walleyes that rarely saw a hook, never heard a motor, and shared waters with pike, moose, and sandhill cranes. DeJong is a big, burly, bearded Canadian, the kind of guy who wears wool plaid when it’s 90 degrees and still uses a tumpline. Together, we hatched a big, burly, river trip in the voyageur style. We’d run whitewater rapids, cross empty lakes, hump our gear through bogs and woods, and fish our way through boreal Ontario. And we’d do it along one of the most historic fur-trading routes in the land of the maple leaf: the Missinaibi-Moose River corridor.

A big Missinaibi walleye. Dusan Smetana

The shortest route between Lake Superior and James Bay, the Missinaibi pours through a 265-mile-long corridor of boreal forest and Canadian Shield rock. In deep time, nomadic bands of Algonquin-speaking natives paddled the river, marking passage with pictographs on exposed cliff faces. (Missinaibi translates to “pictured waters,” after the reflections of these paintings.) Later, Ojibway and Cree plied the river. And from 1740 to 1880, it was a key trading route for trappers from the Hudson’s Bay Co. and North West Co., both of which built trading posts along its banks.

It’s empty country. The stretch of the river from Peterbell to Moose River is classified as “advanced, with difficult portages and remoteness.” David Morin, whose company is one of a handful to outfit trips on the Missinaibi, says few of those who run the river also fish. “They’ll make a couple of casts one night and think that’s all there is to it. It seems that hardcore paddlers just don’t care about fishing. And hardcore fishermen aren’t too interested in dealing with rapids.”

But we were. DeJong and I wanted it all, every totem and cliché of boreal Canada, all rolled into one week in the woods, with paddles and rods in hand. We added to our party photographer Dusan Smetana and Ontario native Lee Bremer, currently doing hard time in e Manhattan financial district. Soon enough, we stood by the CNR tracks in the dark and watched the train’s lights slowly disappear in the distance.

The Tuke

For a day and a half we paddle, float, and fish through gorgeous stretches of river-long, languid pools where mergansers and river otters swim away at our approach. Because the Missinaibi is one of 39 waterways in the Canadian Heritage Rivers System, its banks are protected from logging and development. The result: hundreds of miles of shoreline where ancient trees tumble in water clean enough to drink. Once Smetana reels in a 4-pound walleye near the riverbank. Its flanks shimmer with color. He holds the fish up. “At home in Montana,” he says, “the walleyes are silvery. A little dull. Nothing like this. Such a gorgeous fish.”

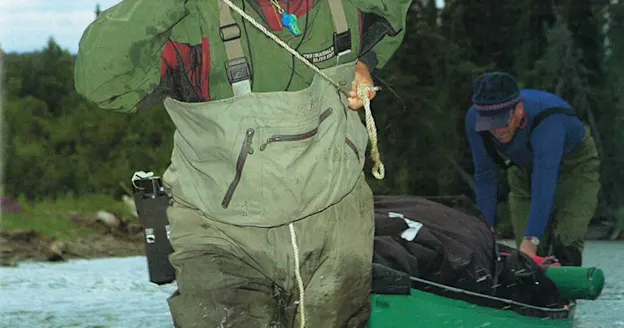

Prepping fish for dinner. Dusan Smetana

We dredge the water for its kin. To get to the bottom of things, I’m tossing an Arctic Fox deep-running spinner and, alternatively, a standard-issue chartreuse leadhead jig. DeJong fires off a Shad Rap, and Smetana swears by his “magic lure,” a Storm Hot ‘N Tot in silver and blue that he picked up at the last minute at a Timmons, Ontario, Wal-Mart. Each time he ties into a fish he sings out in his Slovakian accent, sounding like an Old World peddler, “Lure for sale! Magic lure for sale!” He’s onto something, and he knows it.

I, however, am not. Maybe it’s my Southern nature, my inexperience with any bottom-dwelling fish other than a channel cat. But I’m having trouble with walleyes. Smetana takes a look at my retrieve and sidles over for some quick advice.

“Are you feeling the tuke?” he asks.

“The took?”

“No, no. The tuke.” He sounds out the word; it rhymes with puke. “You must retrieve so slowly that you feel a little tuke. Not a took. It is as if a rock has eaten your lure. Except it is a walleye.”

I give it a whirl. Casting across a current seam, I let the spinner fall to the bottom. I start the retrieve, slowly bump-bumping the lure across the boulders. I feel it drag across a ledge and then the line goes slack as uplifted currents boil off the river bottom, lifting the lure like a leaf in a whirlwind. It drops again, the line slightly taut as the spinner falls, and then tuke!

I set the hook and the rod comes to life.

I know just enough about walleye fishing to know that there are a lot of ways to catch them that don’t involve canoes and white-knuckled rapids runs and long days in wild country. But I’m pretty sure there are none better.

Incident at Greenhill

Our first significant challenge—other than finding fish—comes during our second day on the river. Greenhill Rapids is a 3/4-mile-long cauldron across the backbone of an esker, one of those weird rock formations created by the dragging fingers of a receding glacier. There’s a dogleg turn in the middle and canoe-swamping pillow rocks all the way down. At low water it’s too low, at high water it’s crazy, and when the water is just right it is not to be taken lightly. We play it safe, portaging every bag, pack, and rod for a mile across hill and bog. Then Bremer and Smetana slip into the river. DeJong and I give them a half hour to make it through the rapids, then we push off. When I lick my lips, my tongue is dry as toast.

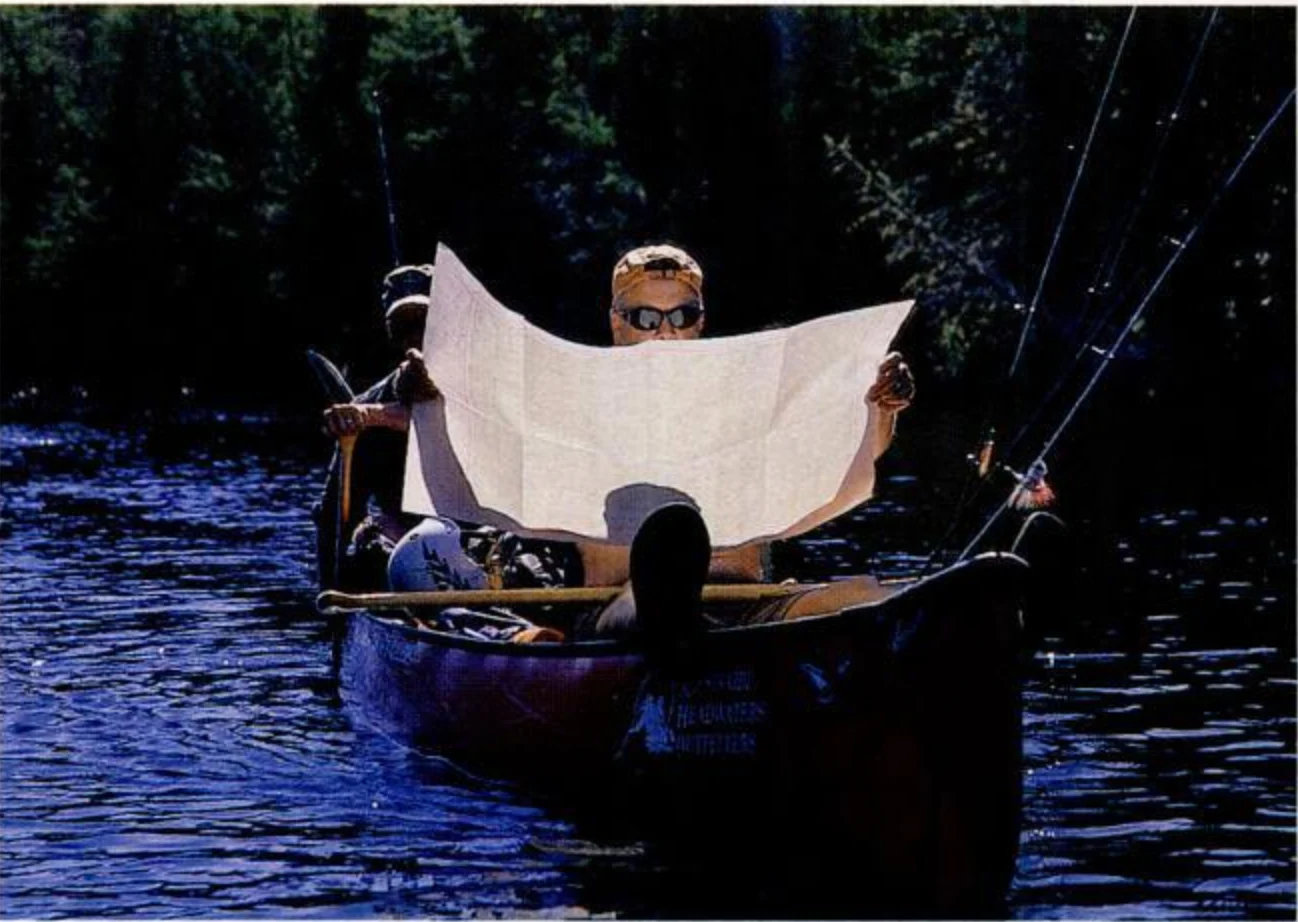

Studying the map, the author plots his route down the Brunswick River. Dusan Smetana

We run the big upper drops cleanly, bashing through high rollers, then eddy out behind a midstream boulder. From here on out there are drops, rocks, and souse holes aplenty, but a straightforward line through the melee beckons. “A walk in the park,” DeJong figures, nervously, as we guzzle a quart of water and congratulate ourselves on a textbook start.

That’s when the wheels come off. I give the boat a strong forward stroke to reenter a hard current line but misjudge my downstream lean. The canoe responds by jerking violently to starboard. As I’m going over I get a glance at DeJong, high-bracing from the bow, but he knows the goose is cooked. In half a second we’re both in the water, the boat between us, out of control.

For a couple of minutes it seems like no big deal. We roller-coaster for 300 yards, but then bigger boulders and nasty ledge drops appear. Our canoe lurches to a stop, pinned against a truck-size rock. The current washes me past the canoe as I make a desperate grab for a gunwale. Upstream, DeJong slips over a ledge and bobs to the surface. My OK sign lets him know I’m unhurt, and he returns it with a grin.

Just then he slams into a subsurface boulder. He hits it hard, the kind of hard in which bones end up on the outside of skin and rescue operations commence. His grin morphs instantly into an O of pain. He slides over a hump of foaming water and comes to an instant stop, his body downstream, right leg pointing upcurrent. The look on DeJong’s face is as alarming as his posture, one foot trapped between rocks on the river bottom as the Missinaibi pours over his shoulders.

Twenty yards downstream, I can do nothing but watch as he struggles to right himself and keep his head above water. If he loses purchase and his free leg slips, the current will sweep him downstream and break his leg, if it isn’t broken already. DeJong strains against the river current, at times completely submerged as he tries to twist out of the snare.

Suddenly he wrenches himself loose. Grimacing, he works across the river, and I gather a rescue rope in case he stumbles again. He makes it to the overturned canoe wild-eyed and panting, soaked and starting to chill. “I’m all right,” he says. For a full minute neither of us speaks. “Strange way to catch a walleye, eh?” he says. We laugh the nervous laugh of a couple of guys who know they’ve dodged a bullet.

After we flip and bail the boat we grind down Greenhill’s boulder garden with no technique whatsoever. Later that night, we camp below St. Peter Rapids. And after dinner we sit back from the campfire, bellies stuffed with fried fish eaten with our fingers-no side dishes and none desired.

“We came awfully close to ending our trip with a very expensive helicopter tour of Ontario,” I say. “Not to mention a week of hospital food.”

“It’s scary how quickly things can turn bad,” DeJong says. “Just when you think you’ve got it figured out…” His voice trails off, drowned out in the roar of the Missinaibi. Cedar smoke curls up toward a red sky, and we turn silent again, until the mosquitoes drive us into the tents.

The Tao of the Walleye

After Greenhill, we fall into a soothing rhythm. We sleep until 7 A.M., when the mosquitoes retreat back to the dark woods. Coffee and breakfast, a half hour of fishing the nearest rapids, then we pack the gear and boats and push off. And the days are long ones. Making camp by six gives us just enough time to fish out the two-hour sunsets. Then it’s a race to get the fish cleaned and fried and eaten before the nightly storm of mosquitoes.

“I love this way of travel, eh?” DeJong says one night, splitting cedar sticks with a small hatchet as I clean a Missinaibi Grand Slam-walleyes, pike, and smallmouth bass. “Making your own way. Never looking at a watch. Living out of a bag.”

Bremer pipes in, “But there’s this inherent conflict on a canoe fishing trip.” Bremer is two years out of college, a thoughtful, competent fellow who has cheerfully suffered days of mindless banter between De Jong, Smetana, and me. “If you’re fishing hard, then you’re not making much progress, and I get this guilty feeling of just wasting time. But if you’re really making miles down the river, you’re probably passing up a lot of good fishing spots, and who wants that?”

None of us. But it’s something we struggle with at every rock and riffle along the way.

Just above Split Rock Falls the Missinaibi turns nasty again. Under jack pines and red cedars, the entire river narrows to a 6-foot-wide cleft in a granite boulder the size of a small apartment building. The V-notch of foaming water disappears with such violence that the idea of running it is laughable. The gear goes on our backs again for the carry up and over a gigantic cliff face.

At the base of the falls is another ideal pool. I imagine walleyes crisscrossed in the water column like firewood, pike cruising the edges. But we catch nothing. We fish the shady, violent chasm at the outfall, the roiling current, the eddy lines, the pool: not a single fish.

In fact, the fishing has been stop-and-go all along. But it’s a hot streak in Ontario, 95-degree days for a solid week, with megawatt sunlight that has to give light-sensitive walleyes a migraine. We fish every conceivable way: fly rods and spinning gear, vertical jigging, bottom bouncing, down-and-across drifting. My companions tell me to quit fretting-by heir standards, the walleye action is among the best they’ve experienced. But I’m having trouble separating the two worlds we’re trying to stitch together: river running and river fishing. One thing’s for sure: I seem to be the only one stressing out over the fish. Once, I paddle back to camp to find Bremer lolling about on a Therm-a-Rest spread over the rocks, reading.

“What are you doing over there, Lee?” I holler. “Reading self-help bestsellers?”

He gazes at me with half-open eyes, content as a cat. “Man, I’m trying to get my life in order. Can’t you see? I’m a mess!” He grins and lies back down.

Massacre at Thunder Falls

It all comes together at Thunder Falls. It’s the last portage of a long day, a full carry of boats and all gear around the highest falls of the trip, followed by a hasty repacking at the base of the falls for a paddle to a sandy campsite on the far side of the pool. Once we get there, we dump our gear. Pitching camp can wait.

We’ve been fooled before, but the place seems fishy. The river squeezes through the upper falls and unravels into half a dozen lower cascades, each one its own fishable stream. We eyeball the torrents, pick our lures, and split up.

My second cast whacks a hammer-handle pike that chops the air with its teeth. I give it a death grip behind the gill plates and twist the spinner from its jaws. That’s when the pike squirms out of my hands and onto the bottom of the empty canoe. It flops like crazy. I scoop it between my bare feet and the canoe paddle, make a grab and miss, then pin it down with a bare foot and kill it with my knife. The canoe hull is coated with fish slime and scales. My feet are smeared with blood. Something clicks in my brain: More.

I see Smetana land a nice walleye, then lose a pair. I hook two more walleyes and another pike. That’s four fish for dinner—enough for us to eat—so now I fish for fun.

When I cast into the boil of whitewater at the base of the falls, a nice 30-inch pike nails the spinner the instant it hits the water, a foot of the fish porpoising above the surface. Vicious. Primal. Its energy seems to travel up the monofilament line and down the rod, into my arms and across my body. After miles and days of tough fishing, the bite is on. The pike breaks me off at the boat and steals my lure, a split second after we lock eyes over the gunwale. I retie and cast like a man possessed.

It’s a place and a time where all the elements of Canadian canoe tripping and wilderness fishing come together—water and rock, a fire on the darkening shore, willing fish, urgency and energy. I fish and fish, landing walleyes and pike, releasing them and landing more.

And as quickly as the fishing fever crests, it retreats. There is a feeling you have when you absolutely must catch one more fish. It matters little whether you’ve already caught two or 20 or 100. One less won’t be enough, but just one more will put everything in balance. Make it all right.

Out where the whitewater trails into foam, I hook a scrawny walleye, and it’s over for me.

I paddle over to Smetana, who has been working a single seam for a solid hour. His blue shirt is buttoned to the neck, collar turned up to fend off the bugs. He is wild-eyed.

The bottom of his canoe is a wrack of fish—pike and walleyes stacked like driftwood. For a moment I think of the 19th-century harvest paintings of fish and game piled high, rabbits and pheasants hanging from pegs, creels overstuffed with trout. I’ve never considered those paintings as depictions of excess but rather of insurance for the uncertain days ahead when the fish might not bite and the game might not move and the children will go hungry.

“You hear of a shooting rampage?” Smetana stammers. “I was on a fishing rampage. I could not help myself. I wanted fish and fish and fish, for tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. It was a good feeling. Do you know this feeling what I am talking about?”

I do.

So we fry fish for a solid hour and a half, under tall black spruces, the smoke scenting the fillets and scattering the bugs, and we drink the last of the Scotch because we know there will not be a better time for it.

A Long Shortcut

A few mornings later we pore over the maps to get a sense of our route’s last few days. The Missinaibi uncoils in a long looping bend to the east. We have some 20 miles left to paddle-beautiful water, but with few rapids to run or swifts to fish. There is, however, an alternative route. I point it out on the map.

The author grabs a keeper fish for supper. Dusan Smetana

A mile west lies Brunswick Lake, a Rorschach blot of blue water with fingers extending in all directions. A series of hatch marks denotes an ancient portage route from the river to the lake. It crosses a trackless swath of green (woods? swamps? who knows?) and ends in a skinny string bog that connects to the lake itself. We don’t know a thing about it except for a scribbled warning in the outfitter’s handwriting: DON’T BE STUPID.

“Hmmm,” says De Jong, with a half-groan, half-murmur of appreciation.

Smetana wrinkles his nose. “I don’t know about that. When the boat floats, it is a beautiful thing. So easy.”

“It’d be going against the captain’s orders,” Bremer chimes in, grinning. “I kind of like that.”

The portage is work, every inch of it. It takes two trips to get the boats and gear to a lily pad-choked bog, where we push the canoes through waist-deep muck. We slip through a screen of wild rice and reach open water at last, but the lake is pounded by a 20-knot wind, with breaking whitecaps and bands of sheeting rain as far as we can see. A fishless day drags on as we grind upwind across Brunswick Lake to our camp on a tiny island with tall red pines and mossy granite boulders. We throw up the tents and get a quick fire roaring to dry socks and boots. Finally, time for the rods.

But conditions could hardly be worse. The wind howls across the miles-long lake. Rain falls in intermittent showers. In the last few hours, the temperature has plummeted 20 degrees. Still, we hunker in the lee of the wind, dredging the dropoffs. DeJong is single-minded, a fine attribute for crazy fishing.

“They’re in here,” he grumbles, casting like a robot.

Cast. Retrieve. Cast.

“They gotta be in here. Don’t you think they’re in here?”

Cast. Cast. Cast.

He suddenly ties into a nice pike that tail-walks beside the bow seat. “Oh, beautiful fish,” he says, but I’m thinking: About six serving pieces. Figuring on fish holding in the pass, we paddle out the inlet between our island and the next in the archipelago, but the wind is too fierce for canoes, and a wall of rain is closing in from the north. We retreat to our island idyll where a fire roils and hunker down under a tarp, stoves sizzling. A pair of loons cries from somewhere out in the monochromatic landscape, cliffs and islands wreathed in fog and spray and spume. DeJong licks fish grease from his fingers. “One more utterly Canadian moment,” he says.

A Brunswick River Tragedy

The next morning dawns calm and clear, perfect conditions to cross the upper reaches of Brunswick Lake. During the night, the wind blew out, and now sunlight drenches the wide open water. We load up on fish off the point of a rocky islet where gulls nest, dive-bombing our boats as we pass. At the lake’s outlet, marshes fringe the shore and funnel us into the Brunswick River, a third the size of the Missinaibi and getting smaller with each paddle stroke. As the river necks down it requires some of our toughest, quickest moves of the trip. Dodging rocks, we careen from bank to bank, ducking under tree limbs, rod tips snagging in the cedars.

At the base of one slot of rapids, we pull out at least a dozen walleyes and a smattering of perch. I hold up an arm-straining stringer worthy of a last-night feast.

“Epic,” DeJong mutters. “Simply epic.”

We’re a mere half mile from our takeout when we run into a gnarly set of rapids. The river pours through a 6-foot-wide channel of froth that runs a couple hundred feet through acres of bare boulders. Smack in the middle is an exposed rock, almost impossible to avoid. “Right! Right!” I yell from the bow, stabbing the water with a draw stroke. De Jong pries the stern in response, but it’s too strong a move. “No! Not that far right! Left! Left!”

We bang our way down the chute. It’s not pretty, but we’re upright and dry, and we eddy out in a pool to watch Smetana and Bremer. I suck in breath as they turn precariously broadside halfway down. They get the boat righted in the nick of time, scrape by the midstream boulder, and plunge over the last ledge and into the pool. Six days of river finally lie behind us.

That’s when DeJong screams from the stern of the boat. “No! No! No!”

I spin around in the bow seat. He holds up a half foot of frayed nylon cord-all that remains of our last-night stringer. “The fish,” he groans. “They’re gone. I forgot to pull them in before we ran the rapids.” He slumps over.

I’m not sure what to say. “This,” he declares, “is a Brunswick River tragedy.”

We spent the last night hungry but also completely satisfied.