We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

There are a number of ways a gun could make this list: The first was to change the course of firearms design. The Remington Nylon 66 made synthetic stocks not only acceptable but desirable, and the Smith & Wesson Model 29 altered our concept of what a handgun could do. Other factors: longevity (the Mosin-Nagant), sheer excellence (the Purdey self-opener), and general-horribleness-but-still-works-like-a-son-of-a-bitch (the Mossberg 500). This list is not compiled in order of greatness. It’s simply the top 50 choices in no kind of order at all. Anyone who would tell you that a Weatherby Mark V is “greater” than an A.H. Fox would teach his grandmother to suck eggs. In any event, enjoy, and when you e-mail to inform us we’re a couple of ignorant swine, check your spelling and punctuation. —D.E.P.

Browning Auto 5

| The Browning Auto 5. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

So forward thinking was John Browning’s long-recoil autoloader design that it took 50 years for any other American maker to come up with an autoloading design of his own. In the A-5′s long recoil action, the entire barrel moved back with the bolt, giving this gun a unique, shuffling kick. But it worked no matter what the weather. It was also a distinctive and, in its own way, handsome gun. An A-5 made in Belgium was the prestige gun among waterfowlers for most of the 20th century, and it’s the gun I started hunting with, too. Mine, with a slug barrel and a full magazine, was deadly when I was a stander on deer drives. Browning moved Auto-5 production to Japan in the ’70s, and while those guns lack the cachet of the Belgian Auto-5s they are every bit as good and tough enough to handle steel shot. The gun was discontinued in 1995, just a few years shy of its 100th birthday. Check availability here. —P.B.

The Ruger 10/22

| The Ruger 10/22. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

This is both the most popular .22 rimfire rifle in the world and, along with the AR-15, the most cobbled-on. A member of the class of 1964, the 10/22 began simply as a nicely designed semiauto rimfire with a magazine that actually fed and an attractive price. Then someone discovered that if you put a match barrel on one, and replaced the factory trigger with a good one, the 10/22 would really shoot. And then it was off to the races. Now Ruger makes its own variants of the 10/22, and if you care to pay a considerable amount of money, any number of gunsmiths will build you something really fancy. And they will all shoot. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Remington Model 700

| The Remington Model 700. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

You could make a good case that this is the first modern bolt-action sporting rifle, because it was the first such gun that was designed for ease of manufacture with little or no hand-fitting. The 700 began life in 1948 as the Model 721 when it became apparent to Remington that the era of cheap, skilled hand labor had come to an end, and gun companies that wanted to survive had better figure out a new way of doing things. The 721 looked cheap and was cheap—but also very, very accurate, so it did very, very well. In 1962 it was replaced by the short-lived Model 725, which gave way to the 700, which turned out to be one of the most successful long guns ever produced. Remington has made millions of 700s in dozens of calibers and innumerable configurations. Model 700s have served as the basis for the U.S. Army and Marine Corps sniper rifles for decades. The Model 700 action has been the heart of more super accurate rifles than any other. How do you do better than that? Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Winchester Model 21 1931–1959

| The Winchester Model 21. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

With graceful lines belying its exceptional strength, the Winchester Model 21 appeared in the midst of the Depression and survived to become an American classic. Joe DiMaggio shot a Model 21. So did a quail hunter from Kansas named Dwight Eisenhower. When John Olin of Western Cartridge Co. bought bankrupt Winchester in 1931, the then new Model 21 came with it. Olin recognized the gun’s durability and devised an extreme torture test to promote it. He gathered the best guns from around the world and subjected them to a proof-load test, feeding each a diet of “blue pill” proof loads until it broke down. The British Purdey failed after 60 shots. The Model 21 survived 2,000 unscathed. Winchester made it in all gauges and grades, from unadorned hunting guns to breathtakingly expensive gold-inlaid, deeply engraved models. While the Model 21 was never profitable for Winchester, it was Olin’s pet project; thus it remained in the line until 1959. Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Co. has brought the 21 back to life, making gorgeous custom 21s today. Check availability here. —P.B.

Hawken Rifle

| The Hawken Rifle NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

The mountain men who “turned left at the Rocky Mountains and headed toward the setting sun” found that the Kentucky rifles they had brought with them no longer fit the bill. The animals were bigger; the shooting distances longer; travel was more by horseback than on foot; and the brass hardware that shone in the sun could cost you your life. Thus, the plains rifle, or, to cite its most famous maker, the Hawken, was born. Samuel and Jacob Hawken built guns in their shop in St. Louis, Mo., and lucky was the mountain man who got one. The guns were heavy (10 to 15 pounds) and heavier-calibered than the Kentucky (the average was .54 and a good many were .58), and their thick barrels were shortened to 30 inches, rarely longer. Maple stocks were replaced by walnut, and the gaudy brass trim gave way to plain iron. A few were flintlock, but the vast majority were percussion. The plains rifle was expected to hit at long range and to knock down whatever it was aimed at. Mountain men thought little of loading their rifles with horrendous powder charges when the occasion demanded it, and a really capable shot was supposed to be able to hit a man-size target at 400 yards. Hawkens had a short heyday. They appeared in the early 1820s and were considered obsolete by the time of the Civil War, when they gave way to cartridge-firing guns. But they stand for a brief and glorious time, and men who have become legends. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Weatherby Mark V

| The Weatherby Mark V Weatherby |

Looking at it now, when it’s been around for 56 years, you wonder what all the fuss was about. But when it debuted, the Mark V was about as radical a rifle as you could imagine. The joint product of Roy Weatherby and designer Fred Jennie, the Mark V departed from tradition altogether. At a time when scopes were not entirely trusted, it had no iron sights as backup. When all rifles were drab wood and dull steel, the Weatherby had a mirror finish on both wood and metal. Two bolt lugs? No, there were nine small ones. It came left-handed, in a time when southpaw shooters were not known to exist by the gun industry. The stock contours were flamboyant. And of course the Mark V was chambered only in Weatherby’s fire-breathing magnums, which redefined high velocity. But above all, the Mark V delivered. All of them, regardless of caliber, had stupendous power and long-range reach, and they were accurate as well. When I was just starting out in the world and poor as owl dung, I spent $250 on a new Weatherby Mark V in .300 Weatherby Magnum. It was a fortune, but I had to have one. A lot of shooters felt that way, and still do. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Savage 220

| The Savage 220 Savage Arms |

Advances in sabot slugs make a 20-gauge the first choice of many hunters, and with the Savage 220, they have a gun to shoot them. Built on the same solid bolt action as the Savage 110, the fully rifled 220 outshoots slug guns that sell for much more. A big part of its secret is Savage’s cleverly designed AccuTrigger, which is user-adjustable down to 1 ½ pounds, yet jolt-proof and lawyer-proof. The AccuTrigger makes shooting so easy that even I have shot an MOA group at 100 yards with the 220′s big brother, the 12-gauge 212. Check availability here. —P.B.

A.H. Fox

| The A.H. Fox. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Inventor Ansley Fox’s automobile is long forgotten, and his self-lighting cigarette never dented the marketplace, but his shotgun is not just the best gun ever made in Philadelphia; it is arguably the simplest, strongest, and best of the classic American doubles. Teddy Roosevelt, who took a Fox on his famous nine-month African safari, called it “the finest gun made.” The original Fox was a well-designed, brilliantly simple gun that hardly ever broke down. Its trim, handsomely sculpted receiver closed with the quiet strength and precision of a Swiss bank vault. You could get it with an excellent single trigger, too, which is rare in double guns. Foxes were made in Philly from 1906 until 1930, when Savage purchased Fox. Although the higher grades of Foxes were discontinued following World War II, Savage made the durable Model B for many years after. The Fox shotgun was revived as a high-grade custom by Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Co. in the 1990s and is still made today. —P.B.

Model 1903 Springfield

| The Model 1903 Springfield. |

This was the rifle that American doughboys carried overseas to fight the war to end all wars. It was also the rifle that turned us from lever-action nation to bolt-action nation. It is probably the handsomest military rifle ever made and one of the most accurate. Caught napping, as it usually is, the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps realized during the Spanish-American War that our Krag-Jorgensen bolt action was badly inferior to the Model 1898 Mauser, and so, with flawless military logic, U.S. designers copied the Mauser—but a little too closely. Mauser-Werke sued the U.S. for patent infringement and won. The rifle, however, was a fine one: highly reliable, long-ranged, dead accurate, and beloved by the troops who used it. Other shooters admired the Springfield as well, particularly hunters. One of these was Theodore Roosevelt, who sporterized a Model 1903 and took it on his 1909 safari. The practice of cobbling Springfields into civilian hunting rifles became the rage and remained popular up until the onset of World War II. Today the old ’03s have almost all been retired, but there is still a certain magic to them. They were there at the beginning of the American Century, and took us a good bit of the way through it. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Remington Nylon Model 66

| The Remington Nylon Model 66. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

In 1959, Remington, which was then owned by DuPont, offered shooters a .22 auto rifle whose stock was made of structural nylon instead of wood. DuPont, being expert in such things, created what was then the most complex industrial mold in the world and in it poured a structural nylon called Zytel. The stocks that came out were an unnatural-looking brown (and later on, other equally creepy colors), but they were also light (the whole rifle weighed only 4 pounds) and indestructible. I had a 66 in college that was never cleaned and functioned perfectly in temperatures of 20 below or colder. An exhibition shooter named Tom Frye, using a pair of 66s, shot at 100,010 wood cubes over 14 straight days and hit all but four. He did not have a single malfunction. People loved the Nylon 66, and in its 30-year life span, well over a million were made. If one rifle established the idea that plastic could be better than wood as a rifle stock, this is it. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Smith & Wesson Model 29

| The Smith & Wesson Model 29. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Every so often, a firearm comes along that redefines things. The Barrett M82A is one such. So is the Remington Nylon 66. And in 1955, Smith & Wesson introduced one—the Model 29, a revolver so much more powerful than any other handgun that it forced shooters to redefine what a six-shooter was. Not only was the Model 29 a veritable hand cannon, but it was a beautiful firearm, as finely made as any factory revolver to date. It was equipped with semi-target sights, exotic-wood grips, a glassy-smooth action, and a presentation box. And then came Dirty Harry Callahan, who did for the Model 29 what no other movie character has done for any other gun—he made it a star. There was a time when you could not buy a 29 unless you paid an insane price for it, and even then it was a struggle to find one. The only legitimate use for the Model 29 is hunting. It’s far too powerful for anything else. Probably, many of its owners fire it a few times and keep it around to admire thereafter. It’s that kind of gun. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

TarHunt RSG

| The Tar Hunt RSG. |

In the days before sabot slugs, people used to boast of deer guns that could hit a 10-gallon milk can at 100 yards. The TarHunt brought us forever out of the realm of minute-of-milk-can accuracy and into the world of M.O.A. slug shooting. Rifled barrels for shotguns had been around for only a few years when TarHunt inventor, Randy Fritz, reasoned if a slug gun was going to shoot like a rifle, it should be built like a rifle. The TarHunt had a glass-bedded, a free-floating barrel, a McMillan fiberglass stock, and a rifle trigger. And, it shoots: the TarHunt can shoot MOA groups, although five shots under 2 inches is more common. By shotgun slug standards, that kind of accuracy is revolutionary. —P.B.

Beretta 680 Series

| The Beretta 680 Series Beretta |

What the Browning Citori is to Americans, the Beretta 680 Series is to the rest of the world. Like the Citori, the 680 Series has been spun off into countless versions from plain hunting guns to medal-winning target breakers to beautifully decorated high-grades. Its low-profile action helps make the gun a natural pointer, and its light weight makes it a pleasure to carry in the field. A large number of American hunters and shooters have discovered the 680 Series along with the rest of the world. That group includes me. I regularly carry a 12-gauge 687 as my pheasant gun. Check availability here. —P.B.

Barrett M82A1

| The Barrett M82A1 NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

The .50 BMG cartridge dates from World War I, and was designed as an anti personnel and anti-matériel round, which meant it could kill a truck as easily as it could a soldier. Its power is simply stupendous, and there is nothing to compare it to in the roster of small arms. After World War II, when surplus ammo for it became available, a few brave souls decided to build guns for the beast that they could shoot for sport. But the rifles were cobbled together in machine shops and garages, and were huge, clunky, immobile, and inaccurate. Enter Ronnie Barrett, who designed the first practical .50. His semiauto was mobile (30 pounds), manageable (it kicks about like a .30/06), dead reliable, and with good ammunition, dead accurate. You say you want to hit at long range? Here is long range in spades. A skilled .50 BMG shooter can hit at 2,000 yards and more. It is so good a rifle that our Armed Forces took only eight years to adopt it. Higher praise than that you do not get. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Mossberg 500

| The Mossberg 500. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Until 1961, O.F. Mossberg primarily made rimfire rifles. Then the company took a risk, putting all of its eggs in a new basket—the Model 500 pump shotgun, which gobbled up space in the factory until the 1980s when Mossberg acquired its first CNC machine and phased out production of all other guns. Nine million Model 500s later, you could say that risk paid off. Don’t let the hardwood stock, plastic parts, and wooden magazine plug fool you; the humble Mossberg 500 keeps on shucking no matter what. While O.F. Mossberg made its reputation producing a good gun at a low price, it has also been a remarkable innovator over the years. Mossberg is committed to the “shooting system” idea that one gun can do it all. As such, it was the first to introduce a cantilever-rifled slug barrel; a completely closed muzzleloading, 209-primer-firing barrel; and a stock with a comb insert that could switch out for a higher one. The Model 500 has served in squad cars and in combat. It’s been the first gun of many hunters, and the only gun of many more. Check availability here. —P.B.

Marlin Model 1895 SSBL

| The Marlin Model 1895 SSBL Marlin |

This stainless-steel and laminated-wood hot rod of a rifle is probably the final flowering of the lever action before it fades into obscurity. Modeled on customized Model 1895s, the SSBL offers such 21st-century refinements as ghost-ring sights, a Picatinny rail, and an oversize lever loop. Chambered for the 141(!)-year-old .45/70 cartridge, which is harder to kill than Dracula, it can be either a light-kicking deer rifle or, with hot loads like those made by Buffalobore, morph into a bone-crushing dangerous-game rifle. The 1895 SSBL is also highly accurate. It’s the only lever gun I’ve ever shot that turned in minute-of-angle groups. If these virtues are not enough for you, the rifle is quick-handling, fast-firing, dead reliable, and moderately priced. If all that doesn’t it make useful in the present, what does? Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Perazzi M Series

| The Perazzi M Series. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Perazzi shotguns earned their 15 minutes of unwanted fame in 2006, when Vice President Dick Cheney shot his hunting partner with one. Target shooters have known about Perazzi since 1964, when Italian trapshooter Ennio Mattarelli won a gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics with a brand-new shotgun he had designed in partnership with Daniele Perazzi. Since that auspicious debut Perazzi has become a household name among shotgunners. It came to America in 1970, imported by Ithaca. The guns combine spirited handling with the strength to withstand thousands upon thousands of rounds. The M series, which debuted at the 1968 Mexico City games, was one of the first guns with choke tubes. It had interchangeable stocks and a trigger group that dropped out for repair or exchange in seconds. Perazzis have gone on to pile up Olympic medals for shooters around the world, most notably, perhaps, America’s Kim Rhode, who medaled in five consecutive Olympics with Perazzi shotguns. —P.B.

Winchester Model 12

| The Winchester Model 12. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Winchester engineer Thomas Crosley Johnson refined John Browning’s Model 97 until it was unrecognizable. The result was the Model 1912. The Model 12 was everything the 97 was—reliable, sure-pointing, and lethal in the field and in combat. It was also everything the 97 was not—hammerless, sleek, and smooth-cycling, earning it the nickname the “perfect repeater.” Many double-gun purists admit the Model 12 handles as well as a break action, and it became a favorite of hunters and target shooters for 50 years. The Model 12 also lacked the modern refinement of a trigger disconnector, so it could be emptied very quickly by holding down the trigger and working the slide, a fact not lost on GIs or on Winchester’s exhibition shooter Herb Parsons, whose rapid-fire feats with a Model 12 amazed audiences. Check availability here. —P.B.

New Ultra Light Arms Model 20

| The NULA Model 20. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

In the early 1980s, a West Virginia gunsmith named Melvin Forbes beheld the average big-game rifle, which weighed 8 pounds, and said: “Why?” Then he set out to build something without all the needless ounces and, in 1985, introduced the Model 20, which, in .308, weighed 5 1/2 pounds with scope. It was not chopped, hacked, or gouged. Its light weight came from a Kevlar stock that weighed only 1 pound and an ingenious design that chipped away an ounce here and an ounce there from the metalwork. NULA rifles will shoot along with the best, and frequently outshoot them. They are indestructo-guns that hold their zero forever. They are, however, twitchy because of their light weight, and without a muzzle brake they tend to kick. Melvin, of course, makes them with muzzle brakes. —D.E.P.

Merkel 200E

| The Merkel 200E. Merkel |

Established in 1898 in Suhl, Germany, Gebruder Merkel produces a distinctively Germanic take on fine shotguns: excellent, over engineered o/u’s and doubles decorated with the deep relief engraving you would expect from the people who invented the cuckoo clock. Banned from importation to the U.S. during the Cold War, the Merkel became, for American shooters, the unattainable Cuban cigar of fine shotguns until the fall of the Berlin Wall made it available again. The 200E, like all Merkels, is built to shoot forever with Teutonic tolerances so tight that it’s hard to open and close without help when it’s brand new. Surprisingly, despite its blocky receiver, the gun is light, lithe, and sweet to handle. Check availability here. —P.B.

Remington Model 1100

| The Remington Model 1100. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

A lot of guns are called revolutionary. The 1100 semiauto actually was. Debuting in 1963, it was in many ways the first truly modern shotgun, designed by an engineering team with the aid of computers and made with mass-production methods developed during World War II. It was even coated with a tough RKW finish that parent company DuPont developed for bowling pins. And it was a semiauto, suiting the postwar taste for firepower. The 1100 wasn’t the first gas-operated autoloader, but it was the first reliable one. It worked, and it didn’t kick. Expanding gas that bled from the barrel drove the action and had the very pleasant side effect of turning kick into shove. Just three years after its introduction, the 1100 was the most popular gun at the U.S. Skeet Championships. Dove hunters, waterfowlers, new shooters—anyone who dealt with recoil—loved the 1100. To this day it remains one of the softest-shooting guns around and seems to fit almost everybody, perhaps one reason there have been over 4 million 1100s produced, with more being made every day. Check availability here. —P.B.

Kentucky Rifle

| The Kentucky Rifle. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

You can call it the Pennsylvania rifle, because most of them were made in that state, or the long rifle, because they were, but the Kentucky rifle it shall ever remain because it came to fame in the hands of Kentuckians like Daniel Boone. A lineal descendant of the German Jager rifle, the Kentucky was a distinct adaptation to the American frontier. It was of small caliber (for the time), usually .40 to .48, flintlock, with a barrel of at least 32 inches and sometimes as long as 48. The stock was almost always maple, and the hardware brass. Most Kentucky rifles had at least a little decoration in the form of stock carving and ornate metal hardware, and a few were out-and-out showpieces. Plain or fancy, however, the Kentucky was accurate. In a time when the average smoothbore military musket was lucky to hit anything at 60 yards, a long rifle could score bull’s-eyes at 300. Over time, the Kentucky was fitted with percussion ignition, and the guns became more and more ornate. But to men like David Crockett and Dan’l Boone, it was the most valuable thing they owned, and often the difference between life and death. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

The AR-15

| The AR-15. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Can a firearm have a stranger history than this one? The M16 (the military version of the AR) was issued as our main infantry rifle in 1966, but its debut was botched to a degree unequaled in the history of military ordnance. Yet it has gone on, in highly modified form, to be our longest-serving infantry rifle. It, and its carbine successor, the M4, is still very much on active duty. Brought on the civilian market in 1965, the AR-15 was virtually ignored until well into the 21st century, but then it caught on with a rush and a roar. All at once, it seemed, younger shooters discovered that the black gun had advantages found nowhere else. The AR-15 is modular. You can tear it down and put it back together in a different form. It is ergonomically superior to traditional rifles. It’s easier to pick one up and hit with it than it is with anything else that I know of. It’s soft-kicking. All the cartridges designed for it are small, and the gas operation and recoil-buffer spring reduce kick even further. And a properly tuned AR with a good barrel and a match trigger will shoot just as well as nearly any bolt action. Right now, the AR is a hugely important part of the firearms industry. It is a cult gun, dearly loved and furiously defended by its admirers. Few rifles are as highly developed or offer as many options for use. Will it replace the bolt action as the sporting rifle of the future? I would not bet against it. —D.E.P.

Sako Quad

| Sako Quad |

This remarkable rimfire rifle makes the list on two counts. Like the Thompson/Center Dimension, it is a switch-barrel gun that swaps easily among four cartridges: the .17 Mach 2, .22 LR, .17 HMR, and .22 WMR. It’s the only rimfire rifle that can do this. And it is unearthly accurate. When I tested a Quad, the two shooters alongside me—experts both—dropped what they were doing to stare, goggle-eyed, at the groups that the Quad was printing downrange. In addition, the Quad is the only rifle I’ve ever seen that will shoot the ghastly and ill-conceived .22 WMR accurately. Buy it with one barrel, or two, or three, or four. It will mostly likely outshoot anything else. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Benchrest Rifle

| The Benchrest Rifle NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Shortly after World War II, in the far reaches of upstate New York and Pennsylvania, small bands of riflemen gathered together to see how accurately they could make their guns shoot. Then they decided to have matches and see who could shoot the smallest group. Thus was the sport of benchrest shooting born, and from it has come most of the knowledge that has revolutionized rifle accuracy in the past 20 years. Benchrest shooters have always been machinists, engineers, gunsmiths, and other mechanically skilled types, and their rifles, which began as monster creations based on standard bolt actions, have evolved into sleek, small, garishly painted affairs of infinite sophistication and near perfect accuracy. A good benchrest shooter thinks nothing of putting five rounds through virtually the same hole. Few people have the patience or the knowledge or the skill to compete in benchrest shooting, but if you meet one of these folks you should thank him. His rifle is why your rifle shoots so well. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Big Sharps

| The Big Sharps 50 NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

If you’re looking for an ancestor to the Barrett .50 BMG and its ilk, here is your rifle. The Sharps Model 1874 was a highly specialized falling-block rifle designed to deliver a crushing blow at long range, and chambered for the .50-90 blackpowder cartridge, which would do just that. Equipped with target-grade iron sights, the 1874 Sharps was called “Old Reliable,” and was the chosen tool of the buffalo hunters, who, in the years from 1865 to 1880, reduced the number of American bison from something under 60 million to 750, as counted in 1890. Buffalo hunters shot from sitting, using crossed sticks, and tried for a “stand” where they could kill the maximum number of animals in one place. They needed both accuracy and power to do this, and an accomplished shot could hit at 500 yards with regularity. The original Model 1874 was made only until 1884, and in small numbers. Other Sharps followed, but the company did not survive. Old Reliable, and the men who used it, passed into legend. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Benelli Ultra Light

| The Benelli Ultra Light Benelli |

While Benelli’s semiautos earned their reputation in the U.S. as waterfowl guns, the upland Ultra Light may be the company’s greatest achievement. A featherlight 12-gauge, the Ultra Light tips the scale at 6 pounds even with a 24-inch barrel, thanks to the weight savings of a shortened magazine tube, alloy receiver, and carbon-fiber vent rib. Its recoil is surprisingly manageable. I hunted with one enough to know that, despite my fondness for the Browning Double Automatic, the Ultra Light is the finest upland semiauto ever. Check availability here. —P.B.

Boss O/U

| The Boss Over/Under Boss |

The Boss o/u, designed in 1909, remains in production today at prices few of us can ever afford. The gun’s innovations, however, paved the way for the Perazzi, the Beretta 680 series, and the Ruger Red Label, among others. Before the Boss, o/u’s opened on a full-length hinge pin and locked up by means of a slotted lump on the bottom of the barrels, which required a tall, bulky, heavy receiver. On the Boss, the hinge pin is replaced with trunnions on the sides of the receiver, and the lumps are on either side of the lower barrel. The result is a gun with a sleek, low-profile receiver that could be made as light and trim as a double gun but with the advantage of a single sighting plane. The Boss established the o/u as the gun of the future. —P.B.

Knight Rifle

| The Knight Rifle NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Tony Knight, a country gunsmith in Lancaster, Mo., changed muzzleloaders forever with his in-line rifles. Knight’s customers, mostly local farmers, came back from blackpowder hunts in Colorado complaining that their traditional muzzleloaders misfired and were a chore to clean. Knight made them a rifle. He moved the nipple from the side to the rear of the breech for surer ignition, and made a breech plug that could be unscrewed for easy cleaning. He shortened the barrel and styled the stock like a centerfire’s. Hunters whose only interest in blackpowder hunting was the chance to spend more days in the deer woods bought Knight’s rifles by the truckload. His guns are the inspiration for almost every muzzleloader on the market today. I shot the one big deer of my life on Knight’s farm with a rifle he later gave me. It’s one of my prize possessions. —P.B.

T/C Demension

| The T/C Demension Thompson/Center |

The idea of interchangeable-caliber rifles is not new; being able to swap out one barrel or cartridge for another while employing the same stock and receiver has a lot of advantages. But until the Dimension, such rifles were highly limited in what you could swap—the cartridges had to have pretty nearly identical dimensions—and they cost a small fortune. Thompson/Center threw all that out the window with a brilliant idea it calls the Dimension. One stock and receiver can accommodate bolt, barrels, magazines, and scope mounts for four different families of cartridges, allowing you to go from .204 Ruger to .300 Win. Mag. with the same rifle. The components for each cartridge family are color coded, so even if you are half-witted and generally inattentive you can’t mix things up. Moreover, the designers of the Dimension had the guts to make this rifle look like something out of a science-fiction movie, with lines that swoop, curve, and plummet. Looks aside, it is one of the most comfortable stocks you will ever clutch. If all that is not enough, the Dimensions I have shot have ranged from accurate to make-your-eyes-bug-out-and-your-face-turn-blue accurate. This is due to an excellent bedding system, a huge amount of clearance between barrel and fore-end, and very good barrels. The Dimension is not a masterpiece of the gunmaker’s art, but it is the product of clever engineers who thought of everything. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Browning Citori 725

| The Browning Citori 725 NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Tinkering with a classic rarely makes it better. Browning accomplished the difficult feat of making over a legend with the Citori 725. The rap on the venerable Citori and the gun that inspired it, the legendary Browning Superposed, has always been that its action is tall and ungainly and the gun is overweight. Browning engineers trimmed metal from the bottom of the receiver, lowering and lightening the action, and thinned the barrel walls, then threw in mechanical triggers just to make target shooters even happier. The result is the liveliest Citori ever, a slimmed-down model that weighs three-quarters of a pound less than the standard model. John Browning would have approved. Check availability here. —P.B.

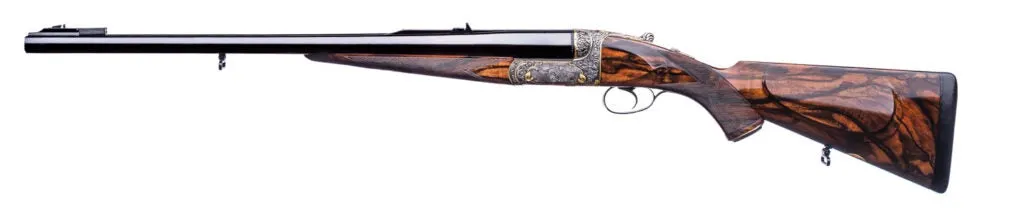

Westley Richards Droplock Double Rifle

| The Westley Richards Droplock Double Rifle Westley Richards |

Very few people have ever seen one of these, or ever will, but if you’re searching for adventure encapsulated in walnut and steel, you’ll find it in this most splendid and specialized of firearms. The double rifle—essentially a shotgun converted to big-bore cartridges—arose in the latter part of the 19th century when British hunters discovered the hard way that they needed gobs and gobs of power to rule o’er large, angry African animals who did not care to be shot. The double rifle was the answer, and the Westley Richards was perhaps the finest of the breed. It was a so-called best gun, meaning that only the finest craftsmen worked on it and all of its components were the finest that could be made. Droplock refers to its trigger-plate action, which could be dropped—literally—out of the receiver for cleaning or repair. (Some of these actions have gold-plated parts, the better to withstand the humidity of the tropics.) Like all double rifles, it was heavy (12 to 15 pounds being common), chambered for huge cartridges, such as the .470, .500, and .577, fast-handling, and, for what it was, quite reliable. If you can look at this gun and not think of the “vast purple and silver silences of Africa,” terai hats, Hemingway, Ruark, Roosevelt, and elephant charges, your brain synapses are not firing as they should. —D.E.P.

Remington 870 Wingmaster

| The Remington 870 Wingmaster NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

If you think of a gun as nothing but a tool, then the 870 is the greatest shotgun ever made. It is the Gun That Works, and if it doesn’t, it easily disassembles to the molecular level in a few minutes, and whatever ails it can quickly be put right. It’s the gun you would take to a desert island. With its stamped parts and pressed checkering, the 870 sold for much less than the machined, hand-fitted Winchester Model 12, the Ithaca 37, and the Remington Model 31 that it replaced when it came out in 1950. Inexpensive as it was, the 870 was every bit as reliable and durable as its costlier competitors. Moreover, it was slender and pointed surely, with the 12-gauge model actually built on the receiver of a 16-gauge Model 11-48 semiauto. The 870 was also slicker than a machine-built gun had a right to be. In the hands of a shooter like trapshooting champion “Mr. 870” Rudy Etchen, there was no beating the Wingmaster in competition or the field. It has gone on to become the best-selling shotgun of all time with more than 10 million made. Check availability here. —P.B.

Jarret Signature

| The Jarrett Signature Rifle NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Today’s shooters think nothing of getting a MOA groups or (much) better from a modest-priced factory sporter, but there was a time when you couldn’t get that kind of accuracy from the very best custom rifles. Until Kenny Jarrett. In the early 1980s, this self-taught South Carolina gun builder decreed that everything that came out of his shop, from varmint guns to dangerous-game rifles, would shoot a minute of angle or better. He was as good as his word. Jarrett changed sporting rifles forever. The Tri-Lock is Jarrett’s own action. It’s built on machinery that has more to do with the aerospace industry than what we associate with the creation of firearms. At Kenny’s shop, I once shot a bolt-action rifle he had built for the .50 BMG, and this veritable cannon, this beast of a gun, put three rounds well inside an inch—just like everything else that says Jarrett on the receiver. —D.E.P.

Purdey Self-Opener

| The Purdey Self-Opener NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Established in 1819, Purdey’s of London builds one grade of double, “best,” and for years purveyed it to kings and counts. The Purdey is still made on the Beesley self-opening action developed in 1879. You’ll pay the price of a small house and wait two years for your made-to-measure Purdey, but the Purdey doesn’t earn its place in this list because of its price. It’s here because it epitomizes the British game gun, which represents the Platonic ideal of a shotgun. Start with wood and steel and cut away everything that’s not a gun, and you’re left with a game gun. Slim, light, ergonomically perfect, and fitted to the owner, it comes as close as any firearm can to becoming part of the shooter. —P.B.

Beretta SO6 EL O/U

| The Beretta SO6 EL O/U NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Beretta is the world’s oldest and biggest arms maker, but it hasn’t forgotten the art of building guns by hand, as evidenced by its beautiful, full sidelock SO o/u’s. The SO5 is the target version, and at $27,000, it’s not cheap. But it’s a bargain when you compare it with other sidelock o/u’s that start at twice that price. The SO6 EL (EL means Extra Lusso, or deluxe) is the more heavily engraved version of the SO5. If you stick to a budget, even in your wildest dreams of Bill Gates–like wealth, the SO5 or 6 is the gun for which you yearn. —P.B.

Winchester Model 70

| The Winchester Model 70 Winchester |

This rifle, another child of the Depression, was introduced in 1936 when skilled machinists were willing to work dirt cheap and gun designs that were complex and required significant hand labor were not yet things of the past. In its heyday, the Model 70 was called “the rifleman’s rifle,” and that was probably not an exaggeration. The Model 70 was a derivative of the Model 98 Mauser, and retained the Mauser’s drop-dead reliability. Winchester came up with a trigger that is still the best that has ever been put in a sporting rifle—a miracle of simplicity and reliability. The Model 70 was chambered for all sorts of cartridges from the smallest to the largest, and in every configuration you could imagine. And it was handsome in the bargain. Production was stopped on the Model 70 with the onset of World War II, and resumed after peace broke out. But Winchester, and the guns it produced, went into a steady decline. In 1964, a new line of Winchester rifles and shotguns was introduced that was easier to produce, and among the guns that vanished was the original Model 70, replaced by a monstrosity that had the same name but should have been strangled in its crib. This story ends happily. Production of the “old” Model 70 was resumed at the company’s South Carolina factory in 2007, and the resurrected Model 70 is far superior to the original. Blasphemy? Pick up one of each, compare them and, especially, shoot them. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Ruger Mark I

| The Ruger Mark I Ruger |

If the Model 110 is the Rifle That Saved Savage, the Mark I is the Pistol That Made Ruger. Now that Sturm, Ruger & Co. is the fourth-largest firearms manufacturer in the U.S., it’s possible to forget that the company started in 1949 with one semiauto .22 pistol, and this was it. Ruger was a true original thinker, and the gun he came up with was dead simple to manufacture, accurate, and reliable; it looked a little like a Luger and sold for the very reasonable price of $37.50. And it held that price for years and years. In a sense, Ruger did for handguns what Remington had done for centerfire rifles with the Model 721—brought them into a new age of design and manufacturing. —D.E.P.

Benelli SBE

| The Benelli Super Black Eagle Benelli |

Back in 1991, the Super Black Eagle—a semiauto with a then unheard-of $1,000 price tag from a little-known Italian maker and chambered for a gimmicky new load—was a gamble. Benelli hit the jackpot. The SBE’s combination of reliability, sweet handling, and long-range capability won over American waterfowlers, who discovered the unique Benelli inertia action to be a model of simplicity and reliability. Because it bled no gases from the barrel to cycle the action, the SBE went forever between cleanings and worked in wet and gritty conditions that could strangle a gas gun. It became the prestige gun among waterfowlers, earning the nickname of the “Arkansas Purdey.” Check availability here. —P.B.

Mauser Model 98

| The Mauser Model 98 NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

When Peter Paul Mauser designed his masterpiece, he had the same object in mind that Mikhail Kalashnikov did nearly a half century later: He wanted a military rifle that worked, period, regardless of what was done to it or not done to it, regardless of where it served or who it served. And he succeeded to such an extent that even though the Gewehr 98 has become obsolete as a military weapon, its action is still prized the world over. There is no shortage of Model 98 actions being manufactured, and there is nothing better. Mauser employed the same principles as Kalashnikov: simplicity, plenty of clearance between parts, and plenty of weight and mass in those parts. The 98 (in a long-barreled version) was the arm with which the Kaiser’s army fought World War I, and a shorter-barreled model, the 98K, served the Wehrmacht for the second time around. What made the Mauser obsolete was not any shortcoming of the gun itself, but the increasing importance of rapid fire, which the 98 could not provide—although it could do everything else. It’s very likely that as long as metallic cartridges are used, Model 98 Mauser-actioned rifles will be in the hands of shooters. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Mosin Nagant

| The Mosin Nagant NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

This unlovely, indestructible Russian service rifle simply refuses to go away. But before we get into that, let us look at its numbers: It was adopted by the Russian army in 1891 and is still in limited service. It was produced in Russia until 1965, and 37 million have come out the factory doors—just in that country. It has fought in 33 wars. As a military small-arms success story, it is exceeded only by its fellow Russian, the AK-47. And now, after more than a century of hyper-accomplishment later, American shooters are buying Mosin-Nagants because they are cheap, reliable, and accurate with upgraded sights. The Mosin is chambered for a rimmed cartridge called the 7.62x54mm, of about the same power range as our .308. It has proved very effective over the years and is still in use in more modern Russian arms. Sneer not at the racks of battered old Mosin-Nagants you now see in gun stores. They have been around longer than you have, and will be here long after you’ve gone, and they have stories to tell. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Winchester Model 97

| The Winchester Model 97 Winchester |

The first pump gun for smokeless powder, John Browning’s Model 97 cut a swath through clouds of waterfowl at the end of the market hunting era. It won championships at trapshooting, including some in the hands of its inventor, a crack shot. The exposed-hammer Model 97 has the feel of the 19th-century harvesting machine that it is; work the slide of a 97, and parts stick out in all directions. And yet, even with this most ungainly action, the gun pointed very well, thanks to its low profile, semi-pistol grip, and slim ringtail forearm. The 97′s hammer can sometimes bite a careless shooter’s thumb, but the gun’s bark is much worse: It holds seven rounds of 00 buckshot, a capability that made the short-barreled trench-sweeper version so deadly in the hands of American soldiers during World War I that Germany protested its use as inhumane. Despite being superseded by the slim, hammerless modern Model 12, the 97 remained in production until 1957. The long-barreled, Full-choke version was a favorite of waterfowlers, and I owned an ancient 97 long enough to add a couple of turkeys to its life list before passing it on to its next owner. In the movies, the 97 is the gun that made the Wild Bunch wild, and old 97s still turn up frequently in cowboy action shooting events today. Check availability here. —P.B.

Krieghoff

| The Remington 32/Krieghoff K-80 NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

With its low profile, fast lock time, and simple, strong sliding-cover lock-up, the short-lived 32 might have been (pause, and look up for lightning bolts) a better gun than its contemporary—the Browning Superposed. For all of its good points, the 32 suffered from horrible timing, introduced in 1932 during the Great Depression, and only 7,000 were made. Its story would have ended there but for Heinrich Krieghoff, an Austrian gunmaker setting up shop in Ulm, West Germany, after World War II, who recognized the 32′s excellence and bought the patent. Krieghoff made the gun first as the K-32, then, in the 1970s, it became the K-80, and so it remains today—an unstoppable, high-end clay crusher that is the choice of many top trap, skeet, and sporting clays shooters. Check availability here. —P.B.

Browning Superposed

| The Browning Superimposed Browning |

John Browning spent his life inventing guns that shot more and faster, but his last creation was the Superposed o/u. The Superposed survived the death of its inventor (Browning’s son Val completed the design), the Depression, and the Nazi occupation of Belgium. Reintroduced in 1949, it became the affordable fine gun of an affluent postwar generation of shotgunners in the 1950s and ’60s. American shooters came to see the Superposed as attainable elegance, and they saved and scrimped until they could own one. You can nitpick: The design is tall and bulky; the sliding fore-end latch is overly complicated; the chambers rust. But the Superposed shoots, and it established the o/u as the glamour gun of American wingshooting. Discontinued in 1976, it remains available as a special-order item, and its form lives on in the excellent Citori, a simplified version made in Japan. Check availability here. —P.B.

Savage Model 99

| The Savage Model 99. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

Arthur Savage’s lever action, which appeared a year before the turn of the 19th century, was as different from everyone else’s lever gun as a jet is different from a propeller plane. It was a sleek gun with no exposed hammer. Rather than a tubular magazine below the barrel, it had a rotary spool in the receiver, so it could accept modern cartridges with spitzer bullets. It had a good trigger. Since it ejected sideways, it could accommodate a scope. And it was chambered for, among other rounds, the .250/3000 cartridge, a light-kicking big-game load whose velocity was, for the time, breathtaking. The 99 was one of those rare creations that is decades and decades ahead of the competition. It was accurate, good-looking, fast-handling, reliable, and affordable. It was in production for 100 years, and if you have a 99 in good shape, take care of it. It will last you yet another century. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Parker Double

| The Parker Double NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

America’s iconic double sprang from humble beginnings: The first Parker shotguns were crude breechloaders made in the 1860s from parts left over from a Civil War rifle contract. Recognizable by a distinctive recessed, slotted hinge pin, the Parkers of the early 20th century came in more gauges, grades, and frame sizes than any other American double. Foxes and Ithacas may be as good or better, but the Parker beats them for mystique. Carole Lombard gave Clark Gable a DHE grade Parker. Czar Nicholas II ordered an A-1 grade gun but never received it before the Russian Revolution brought his reign to a bloody end. Remington bought Parker in 1934 and produced the guns until the demands of World War II production took priority. Check availability here. —P.B.

Winchester Model 52 Sporter

| The Winchester Model 52 Sporter NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

If the Ruger 10/22 is the most popular .22 sporter, the Winchester Model 52 is the best. It was a Depression-era gun, created by installing a sporter-weight barrel and stock on the Model 52 target action. The result is roughly analogous to the Model 70—a mixture of good looks, fine accuracy, and general class that has never been equaled. The 52 Sporter went through four variations and ceased production in 1958, a victim of rising costs. Used ones in good condition bring very substantial prices. —D.E.P.

Beretta 300 Series

| The Beretta 300 Series. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

High-volume South American dove shooting is to U.S. dove hunting what the Daytona 500 is to a drive in the country. A high-volume dove gun might be fired a thousand times before lunch. It gets a quick wipe down before it’s back in action until sunset—day after day. The Beretta 300 Series is the only gas gun that can run with the inertia-operated Benellis south of the equator. That durability makes Beretta semiautos the only repeaters serious sporting clays shooters will even consider. Preceded by the 301, 302, and 303, the 390 was the first Beretta semiauto to offer full 2 ¾- and 3-inch-load interchangeability without switching barrels. The 390 lasted for eight years, and it’s one of those guns you rarely see for sale used, because everybody who was smart enough to buy one isn’t letting go of it. Check availability here. —P.B.

Ithaca Model 37

| The Ithaca Model 37. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

The Ithaca 37 was essentially the Browning-designed Remington 17 built after its patent expired. The bottom ejection feature made it a favorite of duck hunters and left-handers. Bird hunters liked its light weight. The Deerslayer is one of the best slug guns ever. The high price of building the complicated Model 37 has driven Ithaca out of business many times, but the gun is too good to go away, and has returned from the dead more times than Freddy Krueger, with over 2 million made. Check availability here. —P.B.

Savage Model 110

| The Savage Model 110. NRA Museums/NRAmuseums.com |

In 1958, taking its cue from the Remington Model 721, Savage introduced its own collection-of-parts bolt action and called it the Model 110. It was designed by one Nicholas Brewer, and Mr. Brewer knew his business. The 110 was as unlovely a gun as ever went bang. It looked cheap; its stock would have served better as a canoe paddle, and it was cursed with truly abominable checkering. But the 110 sold for a very reasonable price, it shot very well, and it was made in a left-hand version, which was astonishing at the time. And a few decades later, it would also save Savage Arms. Over the years, the company had gone downhill, and when its new president, Ron Coburn, took over in 1988, Savage was only weeks away from closing its doors forever. Coburn asked his engineers, “What can we make that’s good?” He was told, “The Model 110.” And so that was all they made, and Savage took pains to make sure that the 110s really shot, and by and by people noticed. Not only was Savage saved, but the 110 acquired a reputation as being one of the most accurate rifles on the market. Today, there are probably a score of Savage bolt actions in every shape and form, and all are based on the 110 action, which is now considerably slicked up. Among these are very sophisticated, specialized, and expensive target and tactical rifles that would have been undreamed of a couple of decades ago. But even though their price tags go into the several thousands of dollars, their DNA is pure Model 110. Mr. Brewer would be proud, but probably not surprised. Check availability here. —D.E.P.

Field & Stream is dedicated to covering safe and responsible gun ownership for hunting, recreation, and personal protection. We participate in affiliate advertising programs only with trusted online retailers in the firearms space. If you purchase a firearm using the links in this story, we may earn commission