_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

It’s a good time to be a blood-sucking parasite, and not just as a member of the U.S. Congress. Between 2004 and 2016, reports of tick-borne diseases more than doubled in the U.S., a trend that experts say continues. Ticks are now the number one vector-borne cause of disease in this country. (A “vector-borne” disease is passed from one organism to another.) Further, the geographic ranges of many tick species are expanding, driven both by climate change and changing land-use patterns.

Complicating things right now is the fact that the flu-like symptoms of many tick-borne diseases mimic those of Covid-19

. This makes it even more difficult than normal for doctors trying to diagnose and treat Lyme and other tick-borne diseases. In this story, we’ll take a look at the five ticks you need to watch out for, the diseases they cause, and how to avoid the little bloodsuckers in the first place.

What Are Ticks and How do They Feed?

A female deer tick questing—that is, reaching and waiting to cling to any suitable host that happens by. USGS

Here’s a bar-bet winner for you: Ticks are not insects

. They are, rather, arachnids, just as spiders and scorpions are. If pressed, just say that an arachnid is a kind of arthopod. (If really pressed, say that an arthopod is any invertebrate of the phylum Arthropoda. That ought to shut anybody up.) Any one who lives in an area that gets warm and humid at any time of the year, is going to find ticks. They have been with us since the late Cretaceous period, about 120 million years. The earliest tick fossil is preserved in New Jersey amber. It between 90 and 94 million years old.

Ticks are little vampires. They must drink blood to survive. And they’re very patient. A tick seeks its host by crawling up brush or a blade of grass and hanging out there with its front legs splayed in the air, just waiting for a warm-blooded critter to pass by. Then it latches on and feeds. This process is known as questing. While most biting pests—like mosquitoes

—take a bite and move on, a tick buries its curved teeth into a host and stays there for days.

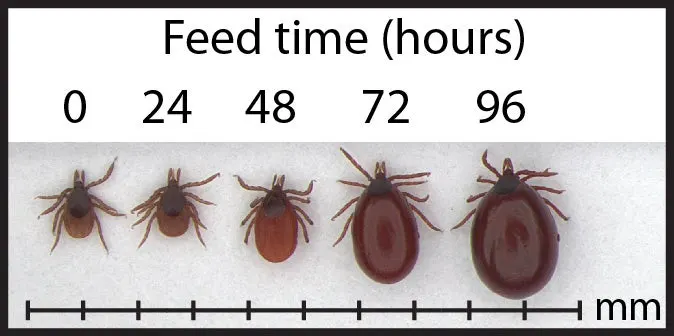

While ticks in the larval and nymph stage attach for 3 or 4 days, an adult female will stick to its host for up to 10 days. That’s a lot more intimacy than I’m comfortable with. A tick even secretes a cement-like substance through its saliva to keep itself glued to the host. It’s thought that ticks need to be attached for 24 to 48 hours before they can transmit and infect. That takes place when their saliva becomes infected and is passed back into the host as they eat your blood. Which, let’s be honest, is really gross.

A deer tick’s life cycle from larva to adult. They can all bite you. CDC

Lyme Disease and Other Tick Borne Diseases

An engorged tick is basically a grab bag of diseases, nearly all of which are nasty, debilitating, and potentially chronic. The standard course of treatment in the U.S. is a course of antibiotics if the infection is caught early. The longer you wait, the more complicated it gets.

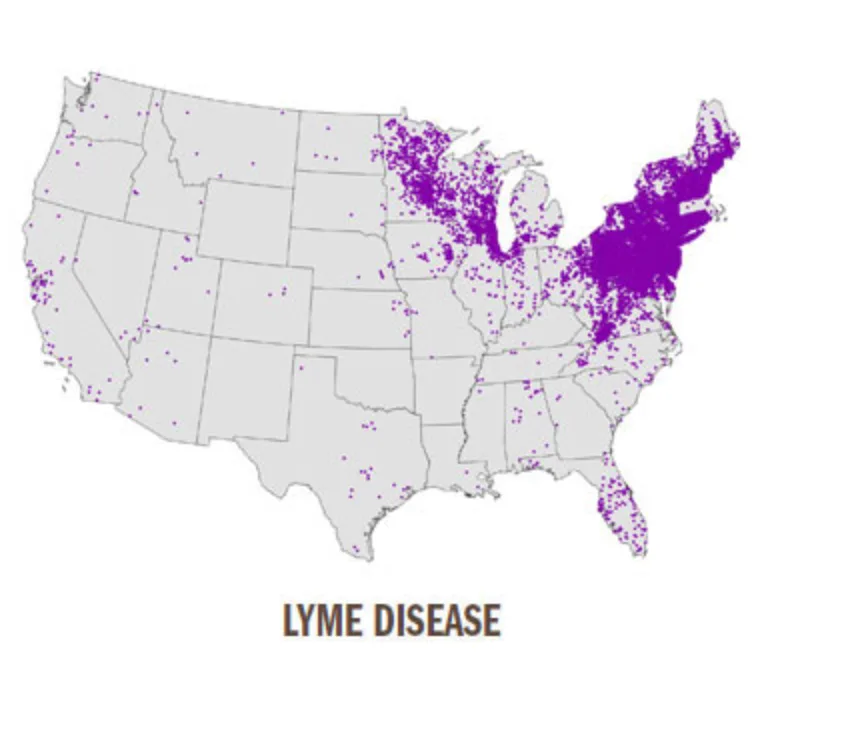

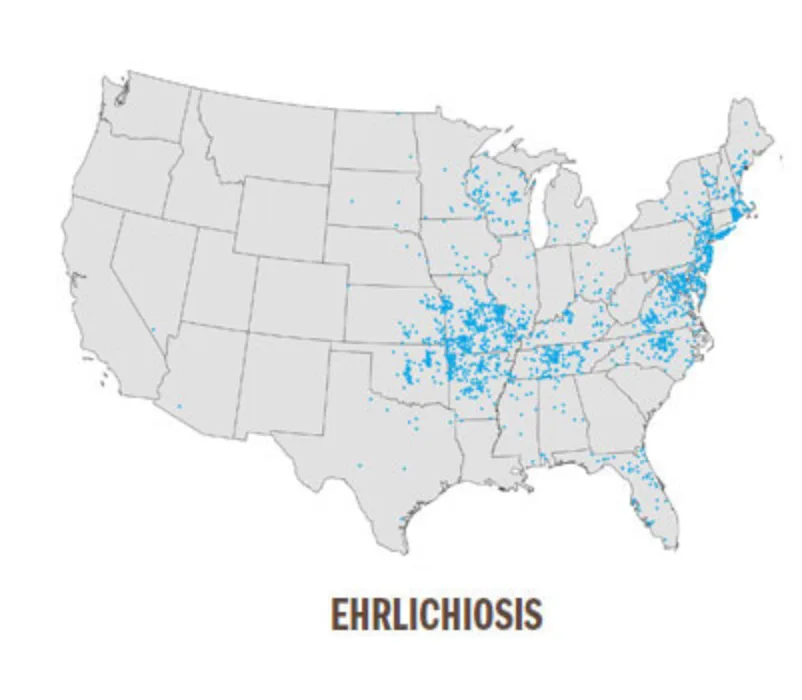

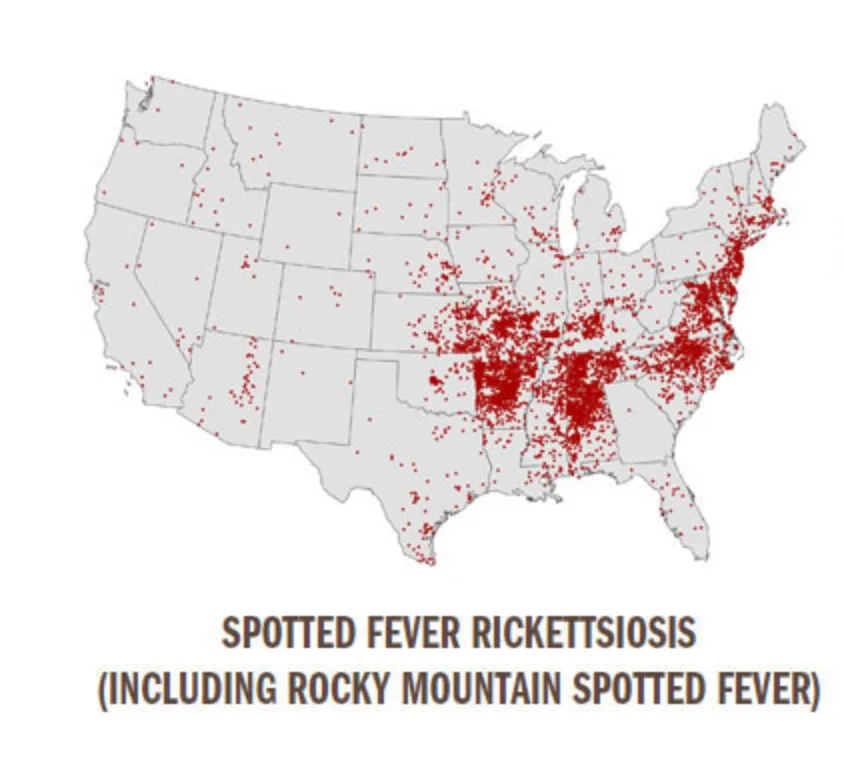

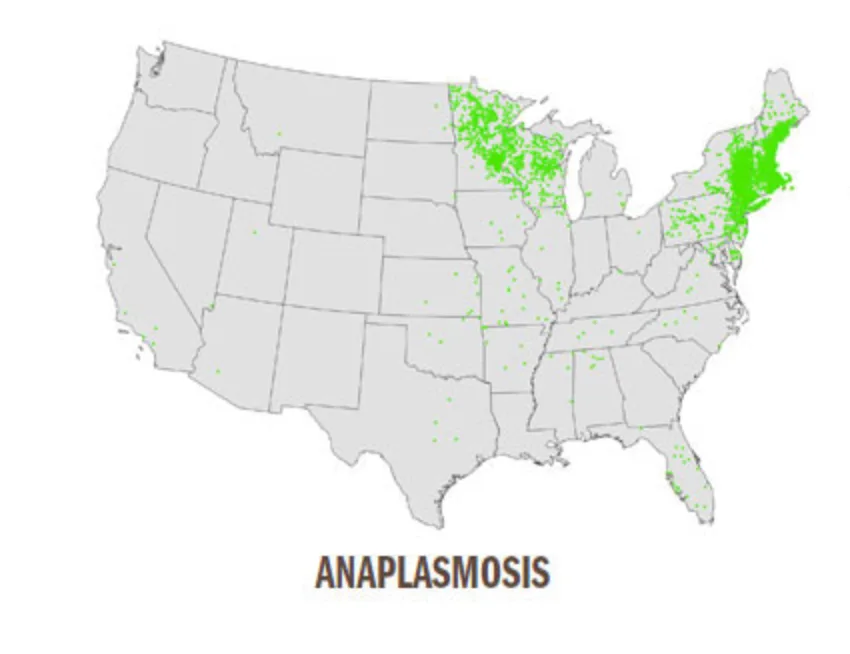

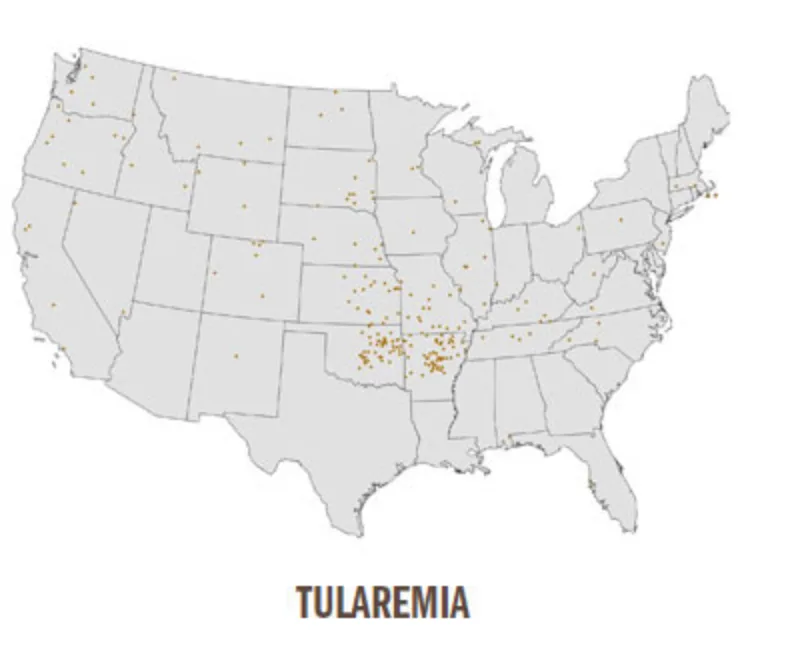

Here is a geographical breakdown of the most common tick-borne diseases across the United States:

Lyme disease results in stiffness, loss of appetite, fever, fatigue, and a host of other symptoms. I had a friend who was diagnosed because one side of her mouth drooped. Such symptoms arise because Lyme disease can damage joints and the nervous system, including muscles in the face. This is known as “facial palsy.”

Ehrlichiosis is a rare disease, infecting just 2.3 people per million, but one you definitely don’t want to get it. Common symptoms include headache, muscle aches, and fatigue. In about 30 percent of patients (and up to 60 percent of children), ehrlichiosis can cause a rash. The disease also blunts the immune system, which results in less resistance to other infections.

Spotted fever is found throughout North America. It causes the usual symptoms—fever, vomiting, nausea, lack of appetite, and neurological problems. More than half of people infected develop a rash on their wrists, forearms, or ankles, although this generally shows up later in the disease. It can be life-threatening if not caught early, especially among older people.

Severe and life-threatening cases of anaplasmosis are, thankfully, rare. Less than 1 percent of patients who seek care for this illness die. But you don’t want this one either, as symptoms include most of the usual discomforts and indignities (though typically milder and for a shorter time). It is usually treated with a course of doxycyclin.

Babesiosis is similar to malaria. In cattle in Texas, babesiosis is known as redwater or Texas cattle fever. Up to half of children and healthy adults who are infected show no symptoms. When they do appear, signs include pale gums, weakness, and vomiting, followed by a fever. It most severely affects older people or those with compromised immune systems.

Tularemia is known as rabbit fever. It affects about 200 people a year, typically young and middle-aged males. Symptoms include fever, lethargy, lack of appetite, and possible death. The face and eyes redden and become inflamed. It’s treated with a variety of antibiotics.

What is the Red Meat Tick Allergy?

Hunters who contract Alph-gal cannot eat the red meat of mammals. Bruno /Germany from Pixabay

Alpha-gal, the tick-borne illness that makes people allergic to most red meat, deserves it’s own special section. As Alex Robinson, our colleague and Editor-in-Chief of _Outdoor Life

_, puts it: Alpha-gal is a hunter’s nightmare. Robinson should know; he developed the illness last year and wrote about it. Here is an excerpt from his story, which you can read in full here

.

I started getting sick in December. I’d get hit with a crippling stomachache that would start an hour or two after almost every meal. Sometimes I’d get sick enough to spend a few hours vomiting in the bathroom. Other times I’d feel a tightness in my chest, and a rash of hives would break out on my skin.

After a few days of this, I went to a doctor who ran a series of blood tests (all fine) and an ultrasound of my gall bladder (also fine). After narrowing my diet to only chicken and rice, and more tests from my doctors, it became clear that I have Alpha-gal syndrome, a tick-borne illness that makes its victim allergic to any mammal-based food product. The disease is carried by the Lone Star tick, and it’s becoming more prevalent all around the country. For hunters like me, contracting Alpha-gal means no more elk backstraps, no venison cheeseburgers—not even a fried squirrel leg.

The meat allergy was first formally described in 2009, according to the New York Times Magazine

. On its info page,

the Centers of Disease Control doesn’t even confirm that the disease is actually transmitted by ticks. There is no cure. But I also found out that if I am not bitten by a carrier tick again, there’s a chance that my allergy could fade over time.

So I cut red meat out of my diet for the rest of the winter and spring. By mid-summer I summoned the courage to try a few slices of grilled venison backstrap. A few hours went by, and I felt fine. Progress.

In some ways, contracting Alpha-gal disease is better if you’re a hunter. I have access to large quantities of wild duck and goose meat, which (when cared for and prepared properly) can be a killer substitute for red meat. On the other hand, my predicament makes big-game hunting trickier. I’ve been a deer hunter since I was 12, and one of the things I’ve always loved about that is the freezer full of venison after a successful hunt. So am I going to take this deer season off? Hell no. Sure, I hunt deer for the meat, but even more so, I do it for the experience. I’ll fill my freezer with ducks and geese, and I’ll spend my deer season enjoying the hunt itself.

I still consider myself a meat hunter, but this fall I’ll just be passing the meat along to someone else. And when I throw the next venison backstrap on the grill for my wife, I might even try four slices.

What Are the Worst Types of Ticks?

While there are 800 species of tick worldwide—and more than 100 kinds in the U.S.—the following five are the ones you should especially be on the lookout for.

1. The Black-Legged Tick (aka, the Deer Tick)

A female black-legged tick, more commonly known as a deer tick. USAPHC, Grahm Snodgrass

Deer ticks are active through the spring, summer, and fall in the Northeast, mid-Atlantic, and Upper Midwest. Even in winter, adults may be out looking for a host if the temperature is above freezing. Larvae, nymphs, and adults may feed on humans. Deer ticks are the smallest tick in North America, with adults growing to about the size of a sesame seed. They are distinctly reddish and have a solid black dorsal shield with long, thin mouth parts.

Found: Widely distributed across eastern U.S.

Transmits: Pathogens that cause Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, and Powassan virus disease.

2. The Lone Star Tick

A female lone star tick is easily identified by a light-colored spot on the dorsal shield. USAPHC, Grahm Snodgrass

The lone star is a very aggressive tick, especially the nymphs and adult females. The greatest risk of bites exists from early spring to late fall. The adult female is noticeable by the white dot or “lone star” on its back. This is the tick that can cause people to have allergic reactions to red meat. I have a friend who now only hunts waterfowl because of this allergy. The lone star tick is medium-size, with a very round body, reddish-brown color, and long thin mouthparts.

Found: Common in the south but also widely distributed in the eastern U.S., where it has been spreading as far north as Maine.

Trasmits: Ehrlichiosis, tularemia, Heartland virus disease, and Bourbon virus disease (which is named after the Kansas county where it was discovered, not the drink).

3. The American Dog Tick

An American dog tick has a numerous white marking on the dorsal sheild. USGS

The greatest risk of bites from this tick occurs during spring and summer. Again, watch out for those adult females. The American dog tick is the largest common tick, is brown in color, and has short pointed mouthparts. They have ornate dorsal shields decorated with white markings and festoons. They most commonly feed on dogs, but can also infect humans.

Found: Widely distributed east of the Rockies, as well as in a limited area of the Pacific Coast.

Transmits: Tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

4. The Brown Dog Tick

A female brown dog tick, shown top and bottom. USAPHC

Dogs are the primary host for ths tick in each of its life stages, but the brown dog tick also bites humans and other mammals. The tick is small, with an elongated body, reddish-brown in color, with hexagonal mouthparts. Unlike the American dog tick, the brown dog tick does not have a decorated dorsal shield.

Found: Worldwide. As in everywhere, and year-round across the U.S.

Transmits: Rocky Mountain Spotted fever.

5. The Rocky Mountain Wood Tick

A Rocky Mountain wood tick cling to a blade of grass. CDC/ Dr. Christopher Paddock

A flat, oval tick, the Rocky Mountain wood tick is brown, but becomes grayish when engorged. Adults feed primarily on large mammals. Larvae and nymphs feed on small rodents. Adults are the ones primarily associated with pathogen transmission to humans.

Found: Rocky Mountain states

Transmits: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Colorado tick fever, and tularemia

How to Avoid Ticks (and Keep Them from Sucking Your Blood)

You don’t have to go to the woods to find ticks. Most yards are full of them. If you want to keep them off you, the Centers for Disease Control says you should avoid heavily wooded or brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter. In other words, stay indoors. Or, if you must be outside, walk in the middle of trails. Well, that advice is fine for plenty of people, but not for hunters and ambitious fishermen.

A deer tick grows to more than three times its original size after 96 hours of sucking your blood. CDC

For us, the experts recommend wearing light-colored clothes, which makes it easier to spot ticks. Tuck pants into socks. After being outside, check the areas where ticks like to attach, which is anyplace where your skin is thin, including your ankles, backs of knees, around the waist, between the legs, underarms, hairy areas, and in or around the ears. The best tick-proofing for clothing is to spray it with a solution containing 0.5 percent permethrin. Never use this on your body. For skin, use Deet, picardin, oil of lemon eucalyptus, IR3535, or 2-undecanone.

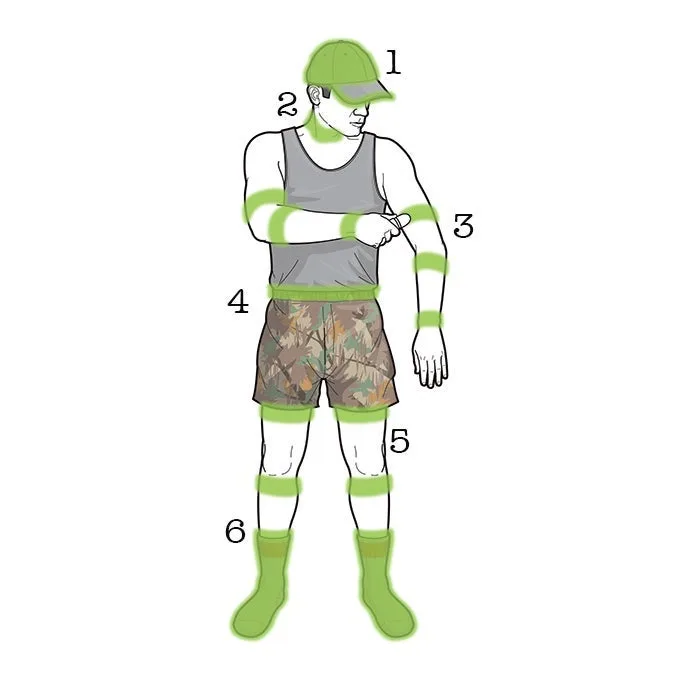

How, exactly, should you use Deet and the like? Here is a 6-step, precision-aplication plan

from editor-at-large T. Edward Nickens. He says this method has cut the number of tick and chigger bites he gets each season by 90 percent.

Apply DEET in these six key places to turn back ticks. F&S

After decades of tinkering, I’ve perfected an insect-protection system that involved the use strong DEET formulations just where needed. I rarely use anything less than 30 percent, and when tick or chigger infestations are high, I use 100 percent DEET without hesitation. The idea is not to cover your entire body, but to draw a few concentrated chemical lines that’ll turn back bugs.

1. Hat Brim and Top

Douse the same hat in repellent every time: Apply it to the crown and brim—and don’t forget the very edge. This will produce a vapor barrier in front of your face but keep the chemicals out of your eyes.

2. Neck

Seal off the first entry point to your torso (from the top) with a stripe around your neck.

3. Wrists and Arms

Stripes above and below the elbow and around your wrists keep creepies from crawling up your arms.

4. Waist

Pull up your shirt and run a stripe around your waist an inch above where your pants ride.

5. Upper Legs

Stripes below the bottom edge of your underwear on the upper thighs and around each leg below the knee ensure that the tick and chigger recon squad can’t move up or down.

6. Boots, Socks, and Pant Legs

Tuck pant hems into socks and run a band of duct tape around the seam. Apply more DEET to boots, socks, and pant legs below the knees.

The Best Method for Tick Removal

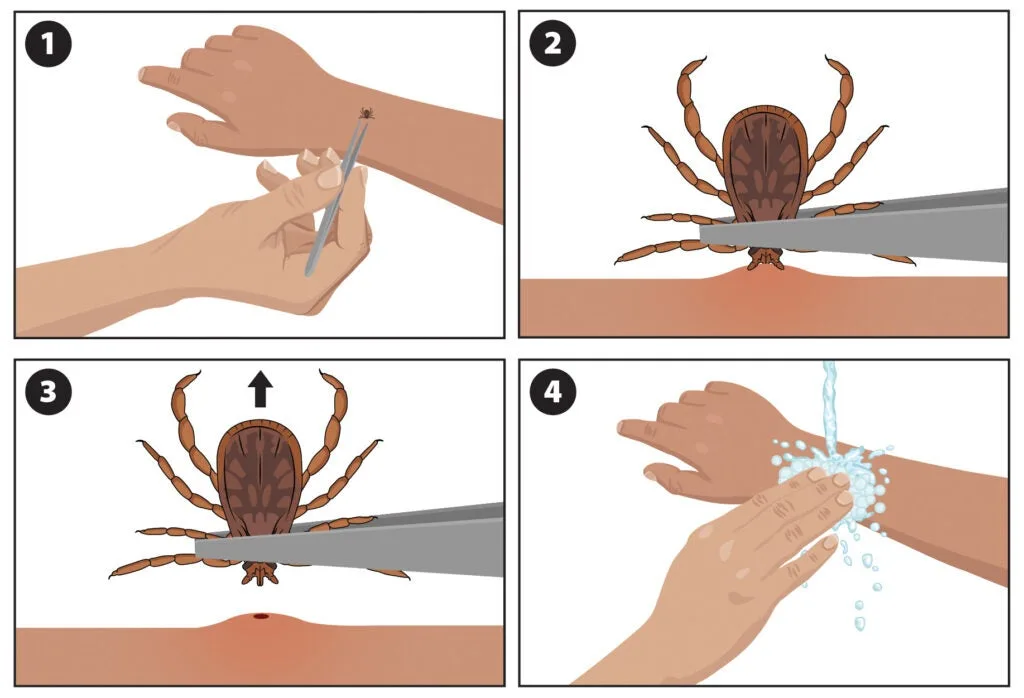

1. Get pointed tweezers. 2. Grasp tick firmly by the head. 3. Pull straight out. 4. Wash the area. CDC

Forget the “alternative” ways of getting rid of an embedded tick. Don’t burn it off. Don’t put Vaseline or nail polish remover on it. Why? Well, a tick can feed off you for a good while before infecting you. On the other hand, a stressed tick will regurgitate the contents of its stomach back into you, which can infect you.

The right way to remove a tick, therefore, is with tweezers. Experts say you want the pointy kind for small ticks, but I’ve used the flat-ended kind on larger ticks with good success. What you do is gently but firmly grab the tick’s head—the part closest to the skin—and pull straight away from the skin. Then burn or torture the little monster in the way that brings you the most pleasure. Unless you want to have the tick tested, in which case, put it in a plastic bag with a stem of grass for it to live on.

What’s the Best Tick Repellent?

The right clothing and sprays will keep most ticks off your body. Collage by Dave Hurteau

If you’re not going to let any little bloodsucker keep you from the woods, then you need to go prepared. The two main lines of defense are tick-repellent clothing and spays. Here’s a quick rundown of what you want. For a more in-depth look at each product, click here.

1. Farm to Fleet Boulder No Fly Zone Socks

Loomed of yarn treated with permethrin, anti-bug socks

are the foundation for a full-body shield against the tiniest invaders.

2. Nite Lite Chigger Gaiters

Leave it to a bunch of raccoon hunters to devise a low-tech, low-cost, why-didn’t-I-think-of-that approach to chigger and tick armor. The

are made of a stretchy synthetic material that you pull over boot tops and pant bottoms for a physical barrier to chiggers, ticks, and fire ants.

3. Rynoskin Total Gloves, Hood, Base Layers, and More

Before you nix the notion of pulling on what is essentially panty hose for your entire body, know this: Rynoskin

apparel is chemical-free and breathable and turns back the fangs of ticks, chiggers, mosquitoes, black flies, and other bloodsuckers.

4. Gamehide ElimiTick 5-Pocket Pant

Permethrin-treated camo outer garments like this one

will keep most ticks from ever making it to your bare skin.

5. Sawyer Permethrin

of 0.5 percent permethrin will treat at least two full sets of clothing and last through six washings. And it works.

6. Repel Sportsmen Stick

make it easy to apply this strong formula exactly where you need it.

7. Thermacell Tick Control Tubes

won’t help with the ticks in the turkey woods, but if you’ve got backyard buggers, they’ll knock them back.