The Quick Buck

There’s no time like the bow opener for patterning and ambushing a trophy buck

It wasn’t just an oak, it was the oak. My friend Tom VanDoorn—a logger and the best big-woods deer hunter I know—and I had scouted dozens of similar trees within a 10-mile radius of his cabin since dawn, and this red oak stood out like a beacon.

For starters, the giant tree grew like its only purpose was to attract whitetails. Situated 3 miles off the nearest gravel road, the oak had 10 acres of swamp grass to its west, a burbling creek 200 yards to its north, and a thick bedding ridge to its east. Every nearby popple whip had been rubbed, and several snapped cleanly off. Dark, wet droppings surrounded the oak, and tentative scrapes disturbed the duff under its sprawling limbs.

But the tree was most notable for what it didn’t reveal: acorns. Tom knows virtually every oak stand for miles, and our scouting walk took us past scores of promising trees. Some had rained acorns, the nuts ankle-sprainingly abundant. Years of hunting the big woods had taught Tom that these nuts were usually wormy and sour; that’s why there were so many left uneaten. Other trees had a smattering of nuts and decent deer sign; these were worth considering. But the tree we focused on had a hog lot of deer sign and barely an acorn in sight. “The acorns taste so good, the deer literally stand under this tree, waiting for them to drop,” Tom said. “They eat every one, then come back the next day and hope for more. We need to set up here tonight.”

We drew straws for a pair of stand sites. Tom won and set up so he could shoot to the oak itself. I pulled the short straw and hung a stand near a fresh scrape in what we figured was a staging area. I got skunked. But Tom arrowed a North Woods giant—a 14-point, chocolate- horned monster that followed a line of rubs right to the tree and into bow range.

That was the opening day of the Wisconsin archery season in 2016, on public land. It was a killer setup—one I’ve replicated many times on the opener, but also one that comes with an expiration date. Our oak was well off the road, but any big-woods grouse nut, or bear guy, or deer hunter worth his salt doesn’t let a little wild real estate intimidate him. Had we found it two weeks later, Tom’s buck might have already been bumped by an English setter or a pack of bear hounds—and found himself another, safer oak.

I tell anyone who’ll listen: If you’re serious about killing a big Midwestern whitetail with a bow, you need to hunt in September, especially the first few days of the season. Yes, the rut is exciting. But with random bucks bouncing all over the landscape, you have to count on a fair bit of luck.

In contrast, if you want to pattern and ambush a specific giant, the season opener is your best shot, bar none. I don’t say it’s easy. But if you know where a good deer is feeding, have a strong hunch where he’s bedding, and are disciplined enough to wait for good conditions, your chances of killing him in the first blush of the season are excellent. A buck’s only concerns now are to eat and to stay alive. As long as you scout carefully enough so you don’t disturb him, that buck is going to go to his food. And with his last human encounter months in the past, his guard is down like it won’t be until, well, next fall’s opener.

The three biggest bucks I’ve put archery tags on—two of them gross Booners—I killed near home in the first week of the bow season. In each case, I knew the buck well, hung a stand for that deer, held out for a good wind, and managed to get it done. I have spent countless hours trying to do the same during the rut and have never pulled it off.

On opening day, the season stretches out like a promise: The first frost, the sudden flurry of rubs and scrapes, the madness of the chasing phase, and even the bitter, last-chance vigils of the late season all lie in front of us. But the best time to arrow a known giant is now. Go get him. —Scott Bestul

Go On a No-Joke Snipe Hunt

For years, I opened the season with snipe. Before there were September doves, early geese, and teal to hunt at home, there were snipe on September 1. Snipe love wet, boggy ground, usually not far from the water’s edge. I won’t lie to you. It’s hot. There are bugs. Mud pulls at your boots with every step. There will be many more snipe when cold fronts push them south later in the year. But it’s an opening day you’ll have all to yourself while others are elbow-toelbow in the dove fields.

Oh, and about that: Doves wish they could fly like snipe. Snipe announce their departure with a nasal scaipe sound, and if they didn’t, we’d never see them in time as they zigzag away. If—I mean, when—you miss, reload, because sometimes these birds will fly back high overhead, giving you a passing shot. Otherwise, mark them down and go flush them again.

By the end of a snipe hunt, you’ll have knocked the rust off your shooting and had a workout. And if you’ve missed more than you’ve hit, chances are no one else saw it happen. —P.B.

Set Out a Waterfowl Buffet

Variety is the spice of opening day for waterfowl hunters in the Midwest. Just about anything might buzz past once the sun comes up. A few years ago, my opener was a perfect small, medium, large, and extra-large waterfowl mixed bag: a drake greenwing teal, a drake wigeon, a drake mallard, and a Canada goose. Each year, the first days of the season here see plenty of resident ducks and geese, as well as migrating gadwalls, wigeon, pintails, and sometimes the odd diver.

There will be days ahead to become a picky greenhead snob. Now you take what the new season gives you with gratitude—except maybe the muddy-tasting shovelers. I let them go and shoot the others.

Bring all of your calls. Mallard quacks work on most ducks, but sometimes it’s best to talk to the birds in their own language. You’ll want a bluewing call, a gadwall call, a wood-duck call, and a whistle for greenwing peeps, wigeon whistles, and pintail trills.

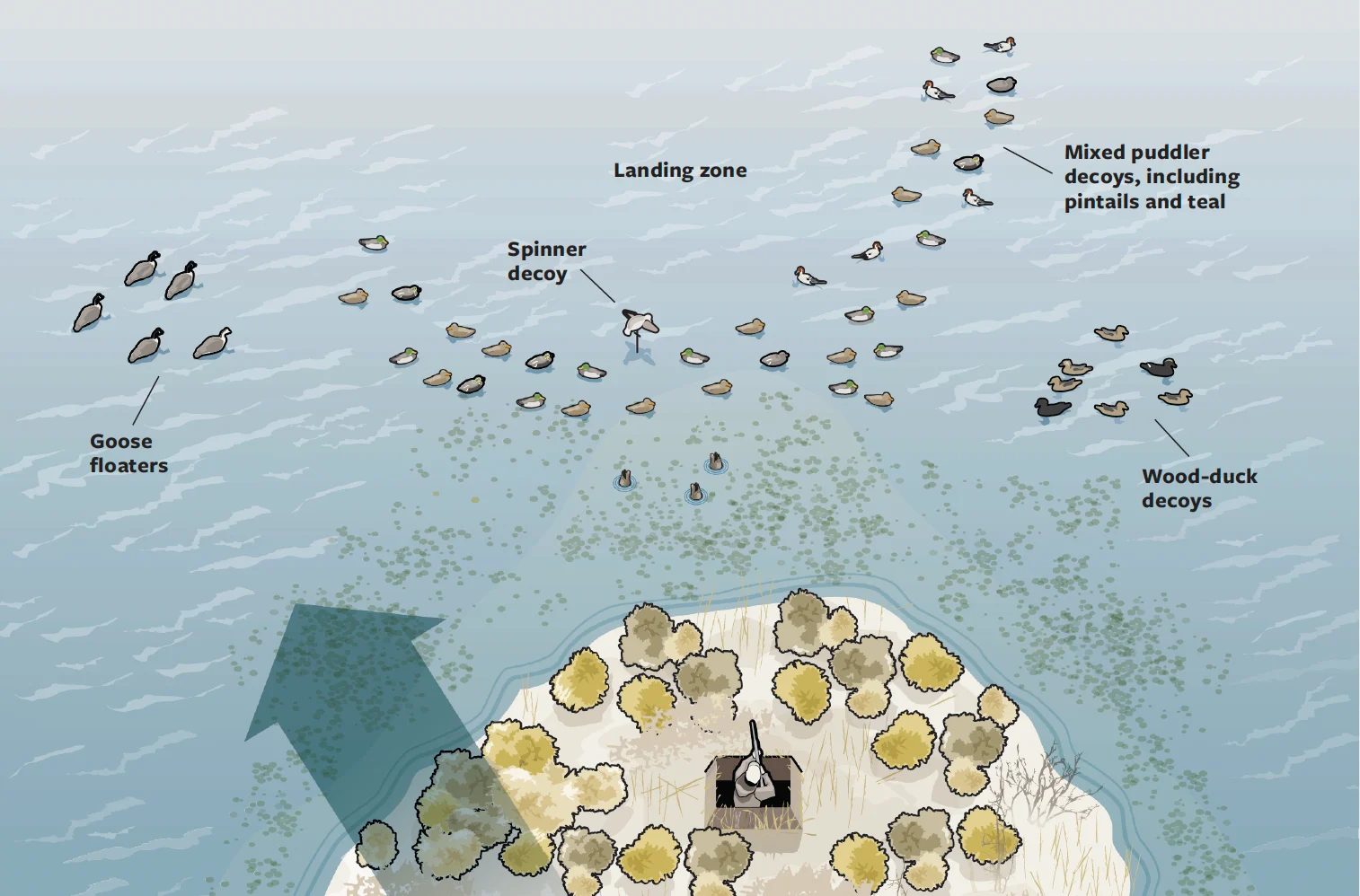

My early-season spread has a mix of ducks with a side order of geese and a pod of wood-duck decoys. I run my duck decoys in a C shape, including a couple dozen mallards, several pintails (for their high visibility), a wigeon or two, and a half-dozen teal blocks. I add a spinner primarily for teal in the center of the C, where the downwind edge of the blocks meet the upwind edge of the landing zone.

Four or five goose decoys are plenty on small waters. They’ll pull in pairs, singles, and small bunches of honkers. These blocks go downwind of the ducks, in keeping with conventional wisdom, which says that ducks will fly over geese, but geese won’t fly over ducks.

Opposite the geese, I put out a half-dozen wood-duck decoys—woodies don’t mix as much with other ducks. And if a wood duck lands outside the decoys, you can sometimes whistle it into the spread. Once the decoys are out, I pour a hot drink, sit back, and see what the new season brings. —P.B.

Keep Cool for Prairie Grouse

The seasons for native prairie grouse open early—long before those for pheasants and often before any other upland opportunity. That means plenty of young birds, which sit obediently for pointing dogs, are there to provide your first upland fix. You’ll generally find sharptails and prairie chickens in ones or twos, although occasionally a whole brood will take wing all around you in what a sharptail hunter I know calls a “popcorn flush.”

The catch: September on the plains of the Dakotas and in Nebraska’s Sandhills is hot enough to pop corn. For the safety of your dogs, you need to cut this big country into half-hour bites. Therefore, you need to know where exactly, in all this grass, those birds are hiding.

Guide Steve Grossman of Wild PrairieLodge says that a prairie grouse’s home range usually centers on its lek, where birds display in the spring. So ask ranchers or biologists where the birds have been dancing and plan your hunt around that. Also, look for Russian olive trees. “We call them ‘bird bushes,’” Grossman says, because there are usually grouse around them. And look for food, including the red fruit of rose hips, as well as buffaloberry, winterberry, and alfalfa.

Make short loops from your vehicle. Carry lots of water and watch your dog for wobbly legs, which signals heat stress. Keep ice in the truck to cool stricken canines. Hunt from sunrise until 11 or so, and then go back out for the last hour. Spend the heat of the day grilling sharptail breasts rare (trust me), and reflecting on the fact that all of autumn stretches ahead. —Phil Bourjaily

How to Hunt Great Lakes Ruffed Grouse

For ruffed grouse hunters in the Great Lakes states, the excitement of opening day is tempered by a sobering realization: September conditions are the toughest of the season. The cidery tang that we all associate with grouse hunting is still aging in the cask; what we often get on opening day is more like a fruity tropical drink.

What’s a grouse hunter to do? According to veteran guide Randy Matis with Classic Bird Hunts in Cable, Wisconsin, the key is to focus on spots where classic, thick grouse cover butts up against some kind of clearing. “I’m looking for old orchards, farm fields, streams, anything that creates a well-defined edge,” he says. “You flush more grouse than you see at this time of year, so it’s important to concentrate on spots where you have the best chance of getting a shot.”

Another reason to focus on this lighter cover, Matis says, is that it often serves as nursery areas where grouse hens lead their broods to feed and sip dew, and, in short, learn how to be grouse. With these young birds still in family units prior to the fall dispersal, they still relate strongly to the places where they lived the good life under Mama’s watchful eye.

The flip side is that with the birds grouped up, a miss is as good as a mile, so there’s no percentage in beating a spot to death. “I move around a lot early in the season,” Matis says. “If there’s ever a time to cherry-pick your covers, this is it.” —Tom Davis

Opening Day Tradition: Haircut Day

The day before opening day was Haircut Day for Ike. He wore a coat of long, feathery tricolor hair that was to burrs as magnets are to iron filings. Even his feet had long hair. Why the inventor of the English setter thought this would be a good feature in a bird dog is hard to guess.

After one season of combing, cutting, and pulling burrs after every hunt, I’d had enough. Dog books suggested I coat Ike in Crisco or Pam before each hunt to make the burrs easier to get out, but that sounded disgusting. Before the next season, I bought electric clippers, and so began Haircut Day. It was the last obstacle between us and hunting season.

Ike hated the clippers. He practiced passive resistance. When I’d haul him out onto the back deck for his annual trim, he’d go limp, Gandhi-like, and play dead. I’d clip away on whichever side of Ike was facing up, then flip his 62 pounds of dead weight over and keep flipping and clipping until all the long feathers were gone and he looked like an English pointer. There would be a pile of hair on the deck big enough to upholster two or three other dogs when I was done—and then we were ready to hunt.

Haircut Day lasted for 12 years. I still have Ike’s clippers, although I don’t need them anymore. Ike’s successor, Jed, is a German shorthair, whose coat is burr-proof. But I keep the clippers, telling myself that I might have another setter someday. The real reason I keep them is that I miss Ike, and his goofy manner, and his no-nonsense nose, and the long, silky, impractical hair. And I miss Haircut Day. —P.B.