THE OLD WEST is mine. I lived it. Ninety-three years have dimmed my sight and made me a little shaky on my pins, but I still have memory. And in memory the old West shines bright.

To see me today, pottering around my daughter Virginia’s home near Redding, California, you might not guess that I was once a quick man with the draw. But I was. Ah, yes, I well remember the day I not only lived history, but made it.

I was 21. On that hot Saturday afternoon in September, 1897, our timber-claim shack in the mountains between Inwood and Mt. Lassen sweltered with the added heat from Ma’s wood-burning cookstove.

The June 1969 issue covered it all—bass, steelhead, grizzlies, and moose meals. Field & Stream

I swabbed the juices of Ma’s venison stew off my mustache and scraped back my chair. “Reckon I’ll mosey up yonder ridge where I got that big buck last week and see what Maje can stir up for me,” I said.

“Good idear, Elias,” Pa said. He always let me off to go hunting on Saturday afternoons. He didn’t hunt much himself, any more. Big strapping German that he was, the hard pioneer life was already edging him toward the grave.

“Tonight is bath night, and don’t be forgettin’ it,” Ma said, slamming the stew bowls into her dishpan. “I ain’t aimin’ to keep this here fire going all night to keep your water hot. And scythe off some of that red brush you’re hidin’ behind. Come Sunday, folks hereabouts might like to get a look at you!”

_“_Folks don’t like my looks can look some place else!” I shouldered my rifle and strode to the door. I didn’t have to call my dog, Maje. He was waiting on the big flat rock we used for a doorstep. He knew it was Saturday.

But first, maybe I should tell you something about that neck of the woods and how we came to be there.

Ma and Pa had brought us to California from Missouri in 1887, when I was 11. They settled on a dry scrub-oak farm near Inwood, in foothill country west of Mt. Lassen. Later, they also bought a timber claim about 12 miles further into high country.

Frontier life was rough and dangerous. Kids weren’t pampered like now. The folks taught us to take care of ourselves. Pa taught me to handle a gun, and I shot my first deer when I was 12. The dark never scared me none. I liked to take my dog and gun and hunt varmints at night. I learned trapping, too. With money from bounties and furs, I bought myself a Winchester .38-55 with reloading track.

Monster Grizzlies

This, the way I figured things, made me a man. From 14 on, I mostly shacked out alone on the timber claim. I split cedar shakes and fenceposts, and shot game enough to feed myself and the family. Sometimes the rest of the family came up for a few days to bring me store-bought grub and to haul out the shakes and posts.

About 1893, some grizzly bears turned up in that area and riled up quite a fuss. A hunter-trapper, called Greasy Baker, killed one. That grizzly weighed 2,100 pounds. [Editor’s note: If this sounds excessive, remember that the California grizzly, now altogether extinct, was a tremendous species. There were a number of authenticated kills of bears weighing 1,600 pounds, and one in Kern County was reported to have been a 2,000-pounder.] The others just disappeared. Some folks allowed as how they had come down from Alaska and went back there.

I had tracked plenty of bear, but those pugs made my blood freeze. The front track measured 11 inches, the hind one, 19!

I don’t know. Alaska is quite some jaunt from Shasta County—even for a grizzly. Anyhow, nobody saw hide nor spoor of grizzly again for about three years. Then, in 1896, Jeff Aldridge, a young fellow about my age who lived on a neighboring timber claim, found all that was left of a dead cow. And near the brutally torn remains, he spotted the biggest bear tracks he had ever seen.

Jeff hightailed his horse to my place. I got my horse, gun, and dogs, and we rode back to the place of the slaughter. I had tracked plenty of bear, but those pugs made my blood freeze. The front track measured 11 inches, the hind one, 19! This beast was a monster.

Jeff and I slapped our horses toward home, set our dogs on the scent, and followed. All that day we tramped the mountains—up timbered slopes, along the ridges, down steep canyons and across their thundering creeks. That bear sure was traveling!

What fouled us up that day was our dogs. Jeff and me, we both had good dogs, but they didn’t like sharing the hunt. As a pack, they were like jealous kids. They spent more time going at each others throats than after bear. At sunset, hungry, bone tired, and disgusted we gave up the chase.

Word of that grizzly raised another whoop and holler. Folks roundabout dropped everything to hunt bear. But like the 1893 grizzlies, that beast just vanished. In a month or so, folks settled down and kind of forgot about grizzlies.

Nothing was further from my mind that hot Saturday afternoon, a year later, when I set off, Winchester over my shoulder and Maje following at my heels.

We passed the smokehouse where strips of last weeks’ buck were curing to jerky. We crossed the clearing, climbed the cedar-rail fence, and strolled off into the timber.

It was a day to make you glad to be tall and strong and young and alive. Maje and I followed Bear Creek to the fork, then turned up the north fork. Ahead, a ridge, timbered green with young fir and cedar, flamed here and there with patches of autumn dogwood.

Above it all, like a queen on her throne, sat old Lassen. Hot as it was, it was hard to believe that the white cape around her shoulders could be snow. And peaceful as it was, who could have guessed that the silent old lady was seething inside, and would someday blow her top?

That September day was like the mountain—silent, peaceful—with no hint of the hot violence about to erupt.

Maje Bays

Maje ranged on ahead, nose to the ground, investigating every clump of brush or berry tangle. He was a yellow dog with an overlay of black hairs along his spine and haunches—half Greasy-Baker-bear-dog, one-quarter shepherd, and one-quarter bloodhound. I had trained him myself, and once he got his nose to the scent, he never gave up.

Now Maje was routing the birds and beasties from a blackberry tangle near the creek. Suddenly he stiffened. The coarse black hairs along his spine rose to a bristling hackle.

His low, throaty growl told me he was on to something. “Go get him, Maje!” I said. He sniffed a couple of circles around the bushes. Then he was off, panting with excitement, across the basin and up the steep slope to the ridges. The sunlight rippled the yellow, marcel-like waves along his flanks. He crested the ridge and disappeared into a growth of thick young firs. I climbed after him, listening, keeping my rifle ready.

Suddenly Maje’s long, wailing bay shattered the timbered silence. It was a mournful, almost bloodcurdling sound—yet it rang with triumph.

I kept climbing. I had almost reached the ridge when something came lumbering through the dense young growth. Not a deer. Even the biggest buck makes a bounding sound.

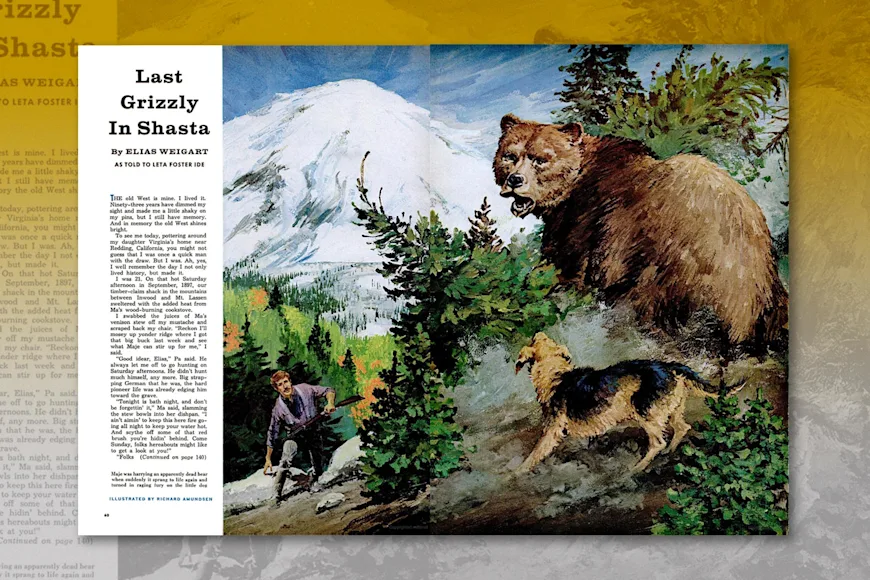

Then, directly above me, a great grizzled, tawny bear lunged out of the young trees, saw me, and stopped.

Fight to the Death

I pulled the trigger. The enormous animal reared up on his hind legs, towered above me a moment clutching front legs like arms around his chest, then hurtled downward directly at me.

I scrambled backward, working the lever on the Winchester and shot again, and again, and again. End over end the great beast tumbled past so close I had to keep scrambling to avoid being crushed. Then he was lost to sight in a deep brushy gully.

I went after him, slipping and sliding down the steep slope. Maje found him first. When I saw the bear again, half hidden in the brush and rocks, Maje was harrying an apparently dead brute. Baying and taunting, he’d rush in close, nip at the great dished face, dodge back.

As I approached, the grizzly suddenly raised his huge head. With an infuriated roar, he caught Maje under his huge grizzled paw, and pulled him under against his chest. Then he slumped again. Maje was pinned, a threshing, screaming bundle of terror, imprisoned between the bear’s head and chest.

I still had two bullets, but the bear’s head was too mixed up with Maje’s frantically thrashing head, tail, and legs. I lost my head. I just plunged in and started beating that bear.

Again the bear rallied. With a throaty roar, he raised his head and lashed at me. Then Maje scrambled free.

I shot the bear then. When he went down that time, I knew he was down to stay.

Yes, I had my moment in history. But, like Pa used to say, “We grow too soon oldt, and too late shmart.” If I had my life to live over again.… But what use are regrets?

The old West is dead. It lives only in the memories of a few old pioneers. My eyes may be dim, but I can still see things young fellows can’t. I can still stare back through almost 72 years—straight into the snarling jaws of the last grizzly in Shasta County.

_You can find the complete F&S Classics series here

._ Or _read more F&S+

stories._