The idea that there are two Alaskas came to me in a cold wave as my canoe was swept into the toppled trees and I was thrown overboard. I caught a glimpse of my pal, Scott Wood, sprinting toward me across a gravel bar, knowing that this was what we had feared the most. Wood -disappeared into the brush, running for my life, and then the river sucked me under and I did not see anything else for what seemed like a very long time.

Every angler dreams of Alaska. My dream was of untouched waters, uncountable salmon and trout, and an unguided route through mountains and tundra. But day after day of portages and hairy paddling had suggested that mine was a trip to the other Alaska, a place that suffers no prettied-up pretense. The other Alaska is not in brochures. It is rarely in dreams. The other Alaska will kill you.

We’d had plenty of postcard moments, for sure: king salmon jetting rooster tails over gravel bars. Tundra hills pocked with snow. Monster rainbows and sockeye salmon heaving for oxygen as we held their sagging bellies. But day after day the four of us had paddled through the other Alaska, scared to death, except when the fishing was good enough to make us forget the fear.

Now the world turned black and cold as the Kipchuk River covered me, my head underwater, my arm clamped around a submerged tree, my body pulled horizontal in the hurtling current. Lose my grip and the river would sweep me into a morass of more downed trees, so I held on even tighter as water filled my waders. The river felt like a living thing, attempting to swallow me, inch by inch, and all I could do was hold my breath and hang on. But I am getting ahead of the story.

Welcome to the Tundra

Give me a canoe, paddle, portage pack, and time, and I can make it down almost any river. For years I’ve considered this a given, and remote rivers have been my express route to fish that have never seen a fly.

It may be that no one had attempted what we set out to do last July: Complete a 10-day unguided canoe descent of southwestern Alaska’s Kipchuk and Aniak Rivers. These are isolated headwaters in the extreme: To get bodies and gear on the ground required five flights in two-person Piper Cub and Super Cub bush planes. Our largest duffels carried 17-foot PakBoats—folding canoes on aluminum frames—which I figured to be our masterstroke. This was part of the dream too: Instead of a ponderous raft, I’d paddle a sleek canoe, catching eddies and exploring side channels. Or so I’d planned.

There were four in the party: myself, photographer Colby Lysne, my friend Edwin Aguilar, and Scott Wood, who more times than not can be found in the other end of whatever canoe I inhabit. Dropping through tundra, we’d first negotiate the Kipchuk through a 1,000-foot-deep canyon. Then we’d slip into the Kuskokwim lowlands, where the river carves channels through square-mile gravel bars and unravels in braids until it flows into the larger Aniak. Some of the most remote country left in Alaska, it is the second-largest watershed in the state, with just a handful of native settlements. We timed our launch for a shot at four of the five Alaska salmon species—kings, pinks, sockeyes, and chums—with a wild-card chance for coho and the Alaska Grand Slam of salmon. We’d been counting our fish for months.

Truth be told, though, no one really knew what to expect on the Kipchuk. According to our bush pilot, Rob Kinkade, less than a handful of hunting parties raft the upper river each year. He’d heard of no one who’d fished above the canyon, ever. As for the paddling conditions—well, he said, it all looked workable from the windshield of a Super Cub. But we weren’t paddling a plane.

The first test came fast, just after put-in. A fallen spruce blocked the channel, with barely enough room to shoulder past. The obstacle looked easy enough to handle, but the water was swift and heavy, and the laden boats were slower to react than we’d imagined. Wood and Aguilar fought to cross a racing tongue of current and were carried straight for the spruce. Watching from upstream, I could hear Wood barking over the rush of water—“Draw right! Right! Harder! Harder!”—as the canoe slipped closer to the tree. They cleared by inches. Wood glanced at us, knowing what we were in for.

“So,” Lysne said, his eyes on the water. “That didn’t look so good.”

Already we were feeling our handicap. With a flyover scouting report of no whitewater, Wood and I had dialed back the level of paddling experience we expected from our partners. Lysne and Aguilar had plenty of remote camps in the bag, but they’d never been whitewater cowboys. Cocksure with a canoe paddle, I figured—as did Wood—that we could handle whatever came up from the stern. What came up was a paddler’s worst nightmare: miles of strainers. Where sharp turns occur, the current undercuts the channel’s outside bank. As the bank collapses, trees fall, wedging against the shore. Water gets through, but a canoe carried into a strainer has little chance of remaining upright—and a body slammed into the underwater structure has little chance of escape.

Rattled, Lysne and I slipped into the fast water and tried to crab the boat sideways with short draw strokes. A big-handed North Dakota hockey player, Lysne tackles obstacles with a brawler’s bravado—a frame of mind that would pay off later. I started to yell as we neared the strainer, and for a second I caught Wood’s concerned look, knowing that in the next moment, the boat would tangle sideways in the spruce and our fishing trip would turn into a rescue operation.

I paddled the strongest half-dozen strokes of my life as the spruce boughs raked across Lysne’s shoulders and caught me in the chest. We pulled away, inch by inch. My heart was pounding. We sidled up to the other PakBoat.

“We cannot capsize,” Wood said, his face intense. “You know that. We simply cannot capsize.”

That night we calmed our nerves with Scotch and pan-fried Arctic grayling, whose bodies had spilled out whole mice when we cleaned them a few hundred feet from our campsite. Wine-red shapes coursed up the pool—king salmon that ignored our flies. But it was early. With each paddle stroke, the fishing should only get better, the paddling easier. I crawled into the tent feeling like a dog clipped by a car. Tomorrow, we figured, it would all come together.

But tomorrow was the day the canyon closed in.

This stretch of the river was filled with more dread and sweat than we’d bargained for—and far less fishing. Every turn in the Kipchuk was a blind bend. Every bend was lined with downed trees. And each time the river narrowed, a chute of blistering midstream flow formed a hard wall of current that threatened to flip the boats.

We were also running a different kind of uncharted waters. Though Wood and I have been to spots where getting through the country proved difficult and dangerous, never had we experienced day after day of serious peril. We wanted the Alaskan wilds, and we didn’t mind pain and sweat for a payoff of unknown country. A taste of fear was part of the price. But on the Kipchuk, we were gagging on terror.

Careful What You Ask For

“There was a time,” Wood said, standing on the bank three days into the canyon, “when I liked being scared in the woods. It made it all seem so…real.” His voice trailed off, and his gaze followed downriver. I knew where his thoughts were taking him. Mine were already there. Home. Wife. Children. “I don’t like being scared anymore,” he said.

Lysne and I pushed the canoe into the river without saying a word. I could only imagine what he was thinking. Lysne never complained, never pointed out that he’d signed on to photograph a fishing trip, not an adrenaline rush down a rain-swollen river. I didn’t voice the thoughts coursing through my own head. The cheerful scouting report notwithstanding, I’d had no business putting inexperienced paddlers in such remote, unknown water. My arrogance was shameful, and the dangers were accruing. Humping gear and dragging boats through 20-foot-tall thickets, where a feeding bear would be invisible at 10 feet, was a necessity. But that’s the seduction of wilderness travel. Each time you come back, you think you can handle more. Until you can’t.

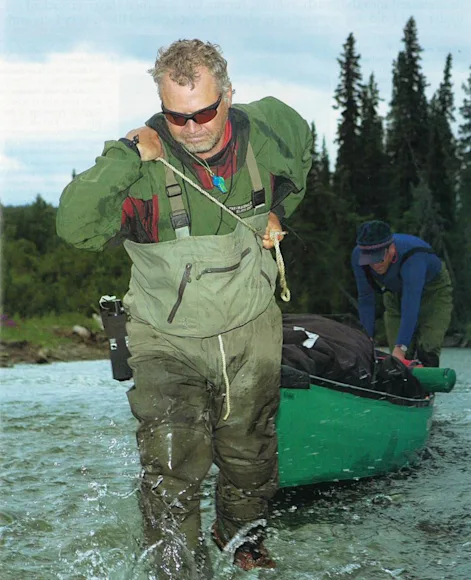

Downstream, the river disintegrated. On the banks, water boiled through 10-foot-tall walls of downed timber as the Kipchuk careened around hairpin turns. Time and time again we roped the canoes around the roughest water, but too often the only choice was to carry everything. To portage the hairpins, we bushwhacked through thickets, taking turns as point man with the shotgun and bear spray. We hacked trails through streamside saplings. We fished in spurts—10 minutes here, 15 there. It took all we had just to keep going.

For long moments I knew I wouldn’t make it. I don’t remember holding my breath. I don’t remember the frigid water. I just remember that the thing that was swallowing me had its grip on my shins, then my knees, and then my thighs.

One night I crouched beside the campfire, nursing blisters and a bruised ego. My back felt like rusted wire. Lysne limped in pain, his toes swollen and oozing pus. I was tired of portaging, tired of paddling all day with little time for fishing, tired of fear. I watched Lysne take a swig of Costa Rican guaro.

“I have to be honest with you,” he muttered. “I’ve had some dark times the last few days. Been f—ing scared and I’m not afraid to say it.”

The night before, he said, he’d dreamed that we were paddling through a swamp, but it was inside somebody’s garage, and a fluorescent alligator attacked the canoe.

“Weird, huh? I wonder where that came from.”

The next morning I dragged myself out of the tent with a mission. Somewhere, downriver, the other Alaska waited.

“Today we paddle like madmen,” I suggested.

“Yeah,” Aguilar groused. “We need to quit being such slackers.”

A few miles downstream we lined a run and dragged the canoes to the head of a deep pool the color of smoke and emeralds. A half dozen large fish held near the upstream ledge. I slid a rod out of the canoe. The first cast landed a pink salmon. My second brought in a chum. I hooted as Aguilar fumed and glanced at his watch.

“Ten minutes!” I pleaded. “I promise, just 10 minutes!”

He huffed and grabbed a rod. Fishing chaos broke out. Wood, Lysne, and I worked a triple hookup on salmon, our lines crossing. We fought sockeyes, kings, and wolf-fanged chum salmon. We landed 3-pound grayling and a solid 26-inch rainbow. One fish ran up the rapids at the head of the pool, leaping like a silver kite. Another was so close that it splashed me. For the first time I felt the pieces coming together. The pull of strong fish was a poultice for ragged nerves and sore shoulders.

Eleven salmon steaks, slathered in chipotle sauce, sizzled over the fire that night.

“We deserved today,” Aguilar said, lying back on a bed of rocks.

“Fishing is fun,” added Wood. “We should try to do more of it.”

Pay to Play

Late the next afternoon, we beached the boats to fish another salmon-choked pool, and in less than a minute we were shoulder to shoulder, working a quadruple hookup. Lysne cackled as my king ran under his bent rod.

It was a fine place to camp and a good time to call it quits, but I’m not fond of camping above a hairy rapid. Just below the pool, a pair of fallen spruce trees leaned over the main channel, then the river bent hard, the bank combed with strainers.

“Let’s get this over with,” I muttered. “We can celebrate when there’s clear sailing ahead.”

“Sure,” Wood replied. “But we were first on the last horrible, terrible, death-for-certain river bend. You’re up.”

The next half minute, Wood would later say, seemed to last an hour. Entering the river, Lysne and I lined up with the route we’d hashed out. Once the laden canoe sliced into the main current tongue, however, it was propelled downstream with terrifying speed. Draw strokes didn’t budge us. Pry strokes and stern rudders proved useless. I lost my hat as we rocketed under the timber. The craft arrowed into a wall of downed trees and suddenly we were tangled in branches, broadside to the current, water boiling against the hull.

“Don’t lean upstream!” I screamed. Lysne didn’t, but in the next instant the river swarmed over the gunwales anyway. The boat flipped, violently, and disappeared from view. The current sucked me under. I caught a submerged tree trunk square in the chest, a blow buffered by my PFD, and I clamped an arm around the slick trunk.

I can’t say how long I hung there. Twenty seconds, perhaps? Forty?

For long moments I knew I wouldn’t make it. With my free arm, I pulled myself along the sunken trunk as the current whipped me back and forth. But the trunk grew larger and larger. It slipped from the grip of my right armpit, and then I held fast to a single branch, groping for the next with my other hand. I don’t remember holding my breath. I don’t remember the frigid water. I just remember that the thing that was swallowing me had its grip on my shins, then my knees, and then my thighs. For an odd few moments I heard a metallic ringing in my ears. A vivid scene played across my brain: It was the telephone in my kitchen at home, and it was ringing, and Julie was walking through the house looking for the phone, and I suddenly knew that if she answered the call—was the phone on the coffee table? did the kids have it in the playroom?—that the voice on the other end of the line would be apologetic and sorrowful. Then the toe of my boot dragged on something hard, and I stood up, and I could breathe.

Wood crashed through the brush, wild-eyed, as I crawled up the bank, heaving water. I waved him downstream, then clambered to my feet and started running. Somewhere below was Lysne. The big-handed hockey player had gone overboard farther midstream than I had and vanished beyond the strainers. Stumbling through brush, I heard Wood give a cry, and my heart sank. I burst into sunlight. Wood was facedown on a mud bar, where he’d catapulted after tripping on a root. Aguilar battered his way out of a nearby thicket. A few feet away, Lysne stood chest-deep in the river, with stunned eyes and mouth open. In his hand he gripped the bow line to the canoe, half sunk and turned on its side, the gear bags still secured by rope.

Our ragged little foursome huddled by the river, dumbstruck by the turn of events. For a long time we shook our heads and tried not to meet one another’s gazes.

Wood finally looked at Lysne. “I can’t believe you saved the boat.”

“It was weird,” Lysne said, his voice rising. “I popped out of the water and saw another strainer coming for me, and I just got pissed off. I was yelling to myself: I ain’t gonna drown! I ain’t gonna drown! I went crazy, punching and kicking my way through the trees. Then boom: I saw the rope, grabbed it, and started swimming.”

I’d lost a shotgun, two fly rods and reels, and a bag of gear, but everything else that went into the river came out.

Aguilar sidled over, quietly. “You okay? I mean, in your head?”

Only then did I feel the river’s grip loosen from my legs. I began to shiver, and no one said a word.

The Cane Pole Hole

“Salmon. Salmon. Salmon-salmon-salmon.” I was counting the kings passing under the boat. Sunlight streamed into the water, lighting up 15-, 20-, and 30-pound chinooks.

Downstream, the Kuskokwim lowlands flattened out—no more canyon walls, no more bluffs: slow water and flat country and easy going.

In the bow, Lysne watched the fish and shook his head. “I just spent a week on the Russian River, shoulder-to-shoulder combat fishing,” he said. “I can’t believe nobody’s here. And nobody’s been here. And nobody’s coming here. Amazing.”

I settled into a cadence of easy paddling, the sort that lets the mind drift free. So far, the price of admission to a place where nobody goes had come close to a body bag. I wondered how much longer I’d be willing to shell out for the solitude. Back home were two kids and a wife and a life I’ve been lucky to piece together. With each year I have more to lose. I’m not ready for an RV and a picnic table, but I couldn’t help but wonder if it was time to dial the gonzo back. I didn’t know. I won’t know, until I hear of the next uncharted river, the next place to catch fish in empty country, and ask myself: What now?

Salmon. Salmon. Salmon-salmon-salmon.

Late in the afternoon we slipped into a deep pool unremarkable but for the 50 kings, pinks, and chums queued up, snout to tail. For 15 minutes they ignored egg-sucking leeches, pink buggers, Clousers, mouse flies, saltwater copperheads, and even a green spoon fly, the go-to choice for hawg bass back home. Downstream, salmon darted across a gravel bar. We could see them coming from 100 yards away.

Wood reeled in and stomped off. He is not one to be snubbed by visible fish. “I’m gonna think outside the koi pond,” he said, following grizzly tracks up the sandbar. Ten minutes later we heard a whoop from inside shaking willows. The tip of a fly rod protruded from the thicket, arcing into the water. “Bring your cane poles, boys,” Wood hollered.

Worming his way through the brush, Wood had flipped a fly into the gravy train of salmon. It didn’t work right away. But ultimately, a pig king had sauntered over to slurp it. No casting, no stripping was required—you just had to keep the fly away from the tykes and hold on. Some of the fish were enormous. Dangling my rod over the salmon, I tried five drifts, 10, no takers, 15 drifts with the pink leech jigged fractions of an inch from the mouths of fish. They stared, looking, looking, l-o-o-o-king, until one sucked it down.

Cackling and howling, the four of us caught king after king, taking turns in the hole. No one cared that this was artless fishing. Dumbed-down salmon whacking was what we needed. A half hour later, Lysne hooked a brute of a king. The 30-pound chinook never showed until Lysne fought it into the shallows. I went in up to my armpits to land it. My hands barely reached around the base of the tail. Lifting the fish was like pulling a log out of the water. When I handed it to Lysne, he groaned. “We’ve got to camp right here,” he said and grinned. “I don’t think I can lift a paddle after this.”

Behind him, chum salmon leapt in the air, and kings sent more rooster tails skyward, their backs out of the water. We flopped on the sandbar and fired up a stove. Mist turned into rain as we scrounged the food bag, poured out the juice from a can of smoked mussels, and sautéed jerk-seasoned sockeye in the makeshift frying oil.

Not 3 feet away, a single chum salmon labored upstream. This one was far past spawning. The sight struck me silent: The fish was rotting, its flanks pale and leprous, the spines of its dorsal and tail fins sticking out above the flesh like the shattered masts of a toy sailboat.

The Land of Easy Living

The next three days brought the Alaska of my dreams. Now the fish came in schools so large that they appeared as burgundy slicks moving upcurrent. There was nothing easy about coaxing them to a fly, and nothing easy about bringing them to hand. We killed one fish a day, enough to eat like kings. One afternoon I was lying back on rocks near grizzly and wolf tracks so fresh that the prints had not yet dried. “This is what I thought it’d be like every day,” Aguilar said. “But now, just one day of it feels so-o-o-o good.”

We’d had moments of fish chaos—multiple hookups, the Cane Pole Hole, outrageous rainbow trout. But fishing remote Alaska isn’t about the numbers, or the variety of species. It’s about the way the fish are seasoned with fear, sweat, miscues, and the mishaps that are the hallmark of an authentic trip in authentic wild country.

On the night before our scheduled pickup, we camped at the juncture of the Aniak and a long, sweeping channel. After setting up the tents, Lysne cooled his heels. His toes were swollen and chinook-red from day after day of hard walking in waders.

“I can’t even think about wading right now,” he said. “I’m just gonna lie here and fish in my mind.”

Wood, Aguilar, and I divvied up the water: They headed off to hunt rainbows down the side channel, while I fished a wide pool on the river.

Since I’d lost my rods and reels when our boat flipped, I fished a cobbled-together outfit of an 8-weight rod with a 9-weight line. It was a little light but heavy enough for the fish we’d landed over the last few days. In an hour of nothing, I made 50 casts to an endless stream of oblong shapes. Then suddenly my hot-pink fly disappeared. Immediately I knew: This was my biggest king, by far. The salmon leapt, drenching my waders, then ripped off line and tore across the current.

The rod bent into the cork, thrumming with the fish’s power. I’d have a hard time landing this one solo, so I yelled for help, but everyone was long gone.

So I stood there, alone and under-gunned, and drank it all in. It no longer mattered if this was my first or 15th or 30th king salmon. What mattered was that wild Alaska flowed around my feet and pulled at the rod, and I could smell it in the sweet scent of pure water and spruce and in the putrid tang of the dying salmon. I felt it against my legs, an unyielding wildness. Part of what I felt was fear, part of it was respect, and part of it was gratitude that there yet remained places so wild that I wasn’t sure I ever wished to return.

Then the king surfaced 5 feet away and glimpsed the source of his trouble. At once the far side of the river was where the salmon wanted to be, and for a long time there was little I could do but hang on.

Adventure stories just don’t get better than this. “The Descent” first appeared in the June 2007 issue.