I WAS A MESS when I first set foot on the place. Looking at the Princeton Marsh, a 1,200-acre Iowa wildlife management area connected to a huge swath of federal bottomland where the Wapsipinicon River flowed into the Mississippi, anyone else would have seen an idyllic hunting spot. But to my 13-year-old brain, it seemed like the dark side of the moon.

Like many teenage boys, I was physically awkward, socially hopeless, and mad at my dad. The last of these was unfamiliar territory for me. Having idolized the man who’d raised me and my sister with such kindness, I was shocked that he’d decided to move the family from my happy boyhood home of Madison, Wisconsin, to Davenport, Iowa. All I knew about Iowa was that it was not home to the Green Bay Packers—or to the grandparents and cousins my world revolved around or the family homestead where I was just learning to hunt.

The author with his first buck ever, taken on his family’s Wisconsin farm, before he moved away. Courtesy of Scott Bestul

We’d lived in a neighborhood packed with kids my age, and every other weekend, we’d make the short drive to see my grandparents, who lived near the 640-acre property homesteaded by my great-grandfather. I’d learned to hunt and fish on that chunk of central-Wisconsin timber transected by creeks and dotted with ponds. The year before Dad moved us, I’d killed my first whitetail buck on the first day of my deer-hunting life, surrounded by uncles and cousins congratulating me. As an adopted kid, I’d always struggled with the feeling of being an outsider, but on that day, I basked in a sense of belonging I’d hardly known before.

The New Kid in a New Town

Then we moved to a place I hated on principle. To me, the town seemed dirty, the neighbors unfriendly, and the girls (an important consideration at the time) all snobs. To cement the deal, I was jumped in the bathroom of my new school on my first day by a tough guy who shook me down for all the money I had on me—one dollar. I plunged into a months-long snit of skipping classes, faking illness, and hanging out with the roughest kids I could find. And just to make sure my parents were paying attention, I poked at my dad’s greatest pet peeve by growing my hair long. He tried to ignore me for weeks but finally marched me to the barber. I pouted the entire ride home, and when we got there, Dad grabbed me by the shoulders and said, “It’s just a haircut, dammit!” It was the first and only time I can remember my dad swearing.

No one in my family had even heard of anxiety or depression—it would take me years to recognize them myself—but Dad offered the only therapy he knew: He took me to the Princeton Marsh on the opening day of pheasant season. Baron, our young golden retriever, tagged along, and the three of us flushed a rooster that rose from a weedy ditch and sped toward a standing cornfield. I shouldered my Remington Model 1100, which was nearly as long as I was tall, and somehow dropped the bird. I hit another later in the day, and when we returned home, Mom snapped a picture of me, the dog, and the birds. She saved the photo for years, probably because it was the only one from that time in which I was smiling.

For the remainder of my teen years, the Princeton Marsh was my go-to hunting spot. It had the usual public-land drawbacks—trash in the parking lots and shot-up signs and fellow hunters who would happily swipe your treestands—but the best parts of the riverbottom could be reached only via a good hike, and those places felt like mine alone. In my senior year of high school, I tagged my first archery buck, a pretty 8-point that walked past the blowdown I was hiding in and stopped to sniff a drag rag at 10 yards. There were other hard-won pheasants, as well as the first coveys of bobwhite quail I’d ever seen and the occasional wood duck or mallard.

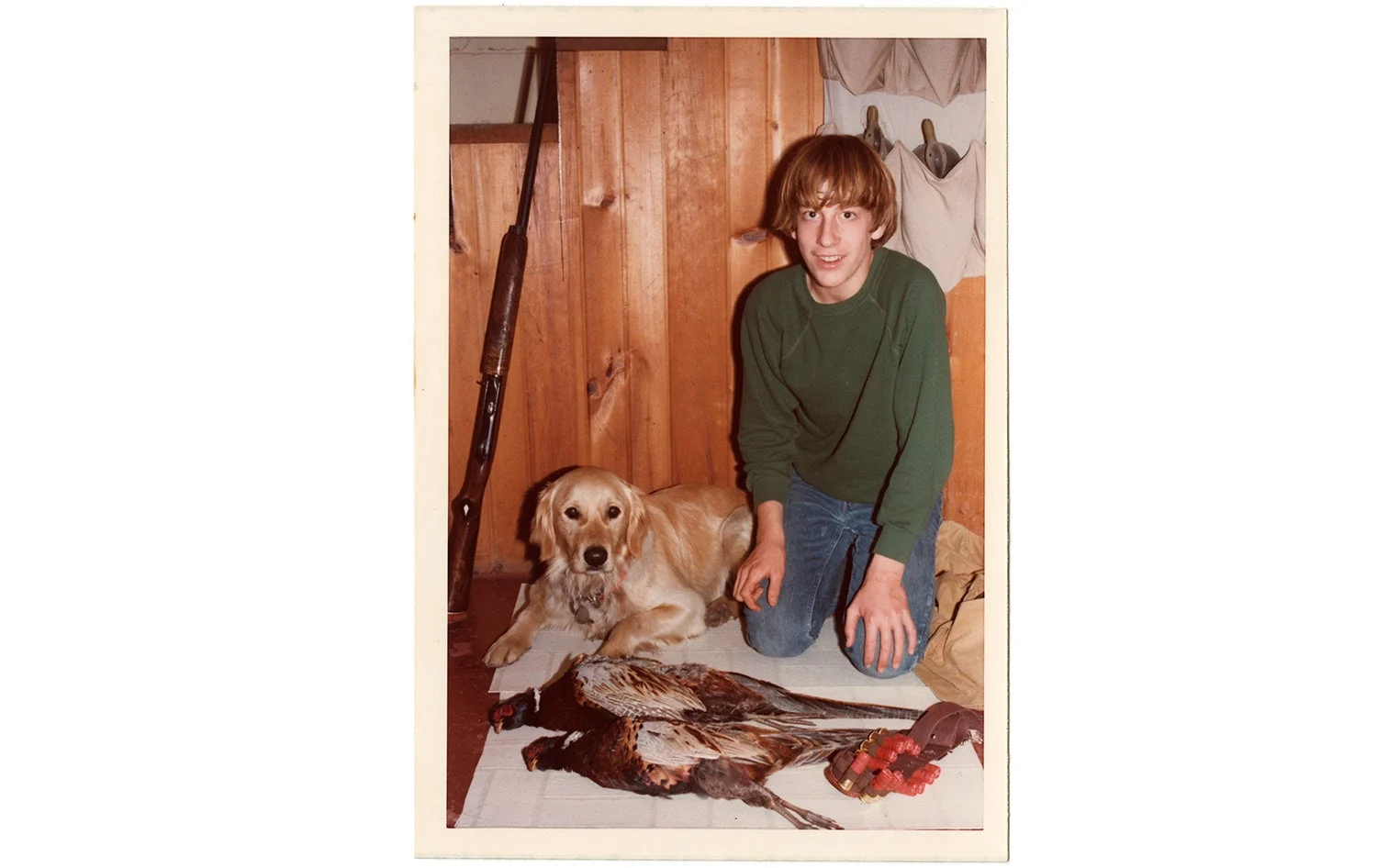

The author at 13, with his golden retriever, Baron, and pheasants taken from the Princeton Marsh. Courtesy of Scott Bestul

And there was no shortage of failures to learn from. One late-October morning a rut-drunk buck trotted in to check a scrape line by my stand, and I sailed an arrow over his back. He was still pawing the dirt when my second shot flew under his belly. He was looking right at me when my third shaft center-punched a skinny river birch covering his chest that I’d failed to notice. As the buck turned to leave, I threw a pathetic Hail Mary, emptying my quiver for the only time in 45 years of bowhunting.

One snowy November morning on a solo hunt, I spent the better part of an hour belly-crawling toward a flock of mallards feeding on a backwater pond—which turned out to be a lovely spread of decoys. But my capstone screw-up was having to be rescued by helicopter from deep in the swamp after a friend and I had gotten hopelessly lost while jump-shooting potholes.

Back to the Refuge

By the time I graduated high school, I’d logged hundreds of hours at that sprawling riverbottom and probably knew it as well as anyone. Yet when it came time for college, my radar pointed north, back toward my ancestral home, and I headed off to a Wisconsin university that promised to make me a wildlife biologist or a game warden.

I thought I’d put Iowa behind me, but the kid who’d moved there at 13 hadn’t matured much in five years. Still painfully shy and unsure how to handle the freedom of adulthood, I managed a spectacular failure in my first semester, and by January I was right back in Davenport. My mom, a fastidious German who considered wasting money among life’s greatest sins, was suddenly bereft of sympathy when she saw my university report card pockmarked with D’s, F’s, and incompletes. “You will get a job immediately and start paying me rent next month,” she said.

I did, but the whole time, I was surrounded by an unpleasant fog that refused to clear. When not working, I confined myself to the sofa, where even the prospect of hunting couldn’t move me. “I don’t know what is happening with you,” my mom said one day while gently stroking my hair. “But you need to get out of here once in a while.”

I began taking long drives in the country on weekends, the same golden retriever who’d flushed and retrieved my first pheasant—and now, seemingly, my only true friend—sitting happily in the back seat. On one such trip, a sign caught my eye. I hadn’t planned it but had driven within a mile of the Princeton Marsh. The car seemed to steer itself, past the same bullet-riddled signs to the lot where I’d parked to start so many of my earlier hunts.

The Burlington Northern train tracks that paralleled the Mississippi bisected the hunting area, and Baron and I walked them now, with the late-winter sun hanging above the treetops. The rails led us past the finger of timber where I’d hung a stand in a river birch and missed a buck four times, and then within view of the weedy slough that had hidden my first rooster pheasant. Far off, I could see the outline of another parking lot, where the rescue helicopter had landed and I’d jumped out to a bevy of sheriff’s deputies, and to the relieved hug of my father.

For the first time in months, I felt the twitches of a smile tugging at the corners of my mouth. I simply stood and breathed, letting the familiar marsh air fill my lungs. The train tracks extended to the horizon, through the marsh and into territory as unknown to me as my own future. Baron continued following the rails, the yellow feathers of his tail wagging, but when he turned to check on me, I called him back to my side. “Sorry, buddy,” I said, but for the moment, I needed to stand a little longer in a place where I felt happy in this world.

_This story originally ran in the Home Issue

of_ Field & Stream_. Read more F&S+

stories._