This story was first published in the June 2005 issue.

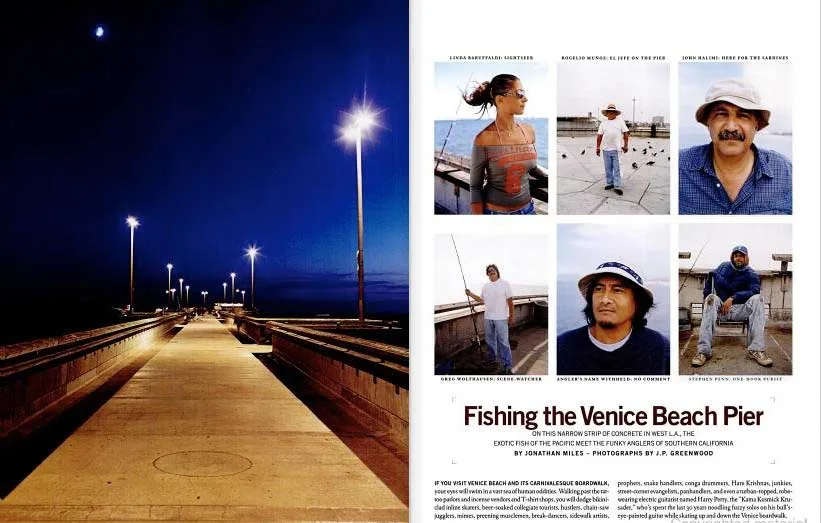

IF YOU VISIT Venice Beach and its carnivalesque boardwalk, your eyes will swim in a vast sea of human oddities. Walking past the tattoo parlors and incense vendors and T-shirt shops, you will dodge bikini-clad inline skaters, beer-soaked collegiate tourists, hustlers, chain-saw jugglers, mimes, preening musclemen, break-dancers, sidewalk artists, prophets, snake handlers, conga drummers, Hare Krishnas, junkies, street-comer evangelists, panhandlers, and even a turban-topped, robe-wearing electric guitarist named Harry Perry, the “Kama Kosmick Krusader,” who’s spent the last 30 years noodling fuzzy solos on his bull’s-eye-painted guitar while skating up and down the Venice boardwalk.

The Dawn Patrol

If you arrive very early in the morning, when the Pacific and the sky are an almost indistinguishable shade of bruised purple and the dark shops along the boardwalk are silent and shuttered, you’ll notice a small cadre of men pushing homemade carts loaded with bait and tackle and plastic-wrapped sandwiches.

In the gloom, they steer their carts to the gate at the Venice Fishing Pier and wait—10, 20 of them, sipping coffee, the orange glow of their cigarettes specking the dark as they wait for the pier guard to drowsily unlock the gates at 6 A.M. These are the fishermen of the Venice Pier, and when the gates open, they stream forward and take their positions along the pier’s 1.310-foot length. Then, the low mumble of the waves is quickly joined by the whir of lines being cast, by the wet plunk of sinkers hitting the water, by the happy reel-screech of a fish on.

Pier of Dreams

If the Venice boardwalk is a human circus, as many observers have described it, then the long, keyhole-shaped pier that abuts it is an angling circus, a narrow strip of concrete where the exotic and unpredictable denizens of the Pacific Ocean—needlefish have been reeled up onto the pier; occasionally someone books a sea lion—meet the exotic and unpredictable anglers of Los Angeles.

Piers attract a different sort of fisherman than, say, lake edges, and certainly streamsides—different that is, though fundamentally the same. For those without the cash or gas or stamina to fish for Castaic Lake largemouths or San Gabriel River rainbows, or to charter a boat and head out to sea, a humble pier can be a thing of beauty. And the fact that no fishing license is required on California piers gilds the lily.

Some anglers revel in the social aspects of the fishing, the easy fellowship of a pier rail. For others, consistency is the draw. “If you have the soul of an artist and can see and feel the rustic charm of old…structures that have long withstood the lash of time and tide,” wrote Raymond Cannon in How to Fish the Pacific Coast in 1953, “you will at once recognize something of the hypnotic spell that compels addicts of pier fishing to return again and again, day after day, to the same old spot. Fish or no fish, rain or shine, you will see them, happy, cheerful, and contented, ensnared in the mesh of a magnetic net of their own mental creation.”

Sympathy From the Devil

That same old spot, for Stephen Penn, is beside a graffiti-coated trash barrel on the left side of the pier end, with a view south toward Marina del Rey. This is where nearly every morning, Penn plants his folding chair and sets up a medium surf-casting rod, equipped with a secondhand Shakespeare reel, as well as a telescoping baitcaster with a length of 20-pound-test line tied to the last eye. He baits the hooks using mussels or razor clams, casts out toward an artificial quarry-rock reef, settles deep into his chair, and prays that the devil” won’t leave him fishless that day.

When I met him, the devil hadn’t let him catch a fish all week. “I set my pole up with one hook,” he said, as if asserting the purity of his tactics over those of neighboring anglers throwing a two-hook high-low leader. “One hook, one fish. That’s all I want. Won’t that devil please give me just one fish?” A native of Youngstown, Ohio, where he grew up fishing for walleyes and perch, Penn is a singer and songwriter who once, he claims, wrote a song with funk legend George Clinton.

But Penn fell on hard times, did some literal hard time in prison, and now, homeless, spends the bulk of his days fishing in Venice while composing songs in his head—love songs, mostly, because they make people happy. “It’s kinda hard to get back on your feet,” he says. “But this is good. I get to sit out here every day thinking about lyrics and notations and sometimes I can catch me some fish. Not today, though. I’m just making music today, Rojas, he’s doing all the catching.”

Numero Uno

Rojas is 56-year-old Rogelio Muñoz, a big-shouldered. round-bellied native of Zacatecas, Mexico, who’s lived in L.A. for two decades. Everyone calls him Rojas, and he’s the unofficial boss of the Venice Fishing Pier. On the weekends, he is the first to arrive at the gate. If the guard is a minute late, Rojas bangs on the gate’s bars, and because he is the boss, the gate quickly swings open. Often joined by his three nephews, Rojas lords over the 120-foot-diameter circular end of the pier, with his five rods spread widely along the railing. He is a serious, determined fisherman and is almost always busy: dispensing advice, barking orders, tying leaders for his nephews or for the other Mexican fishermen who bow to his expertise, all the while eyeing his lines with the frowning intensity of a football coach. spitting sunflower seeds to the sea.

He can be magnificently productive. “One day,” a fellow fisherman boasted, “I saw him catch nine sharks.” At times, usually in the afternoons when the action is slow, he naps on the concrete, lying flat on his back; he is almost never disturbed. If he is, it is only because someone has caught a big fish, and the boss likes to inspect any big fish.

When I first encountered him, he was hoisting up a sand shark, snagging it with a heavy treble hook attached to a foot of chain and a length of cotton rope, and raising it past the mussel-encrusted pilings. A crowd gathered around him as he slapped the shark onto the concrete, wrestled it still, and fetched a tape measure from his pocket ” Cuarenta y cuatro,” he announced—44 inches. Onlookers and passing joggers watched with expressions of distaste. The natural world can seem startlingly alien to Los Angelenos.

Once the inevitable photo was snapped. Rojas dragged the shark across the concrete to a shady strip beside the pier rail, where it would remain throughout the long day. One of the curiosities of the Venice Pier is that hardly anyone seems to bring coolers. Fish to be kept are unhooked and then dropped, unceremoniously, on the shadowed concrete beside the rail. You can’t spark a conversation by asking a fisherman about the day’s action; the answer lies gasping at his feet.

“The funny thing about Rojas,” another angler confided to me, “is that he doesn’t even like to eat fish.” Catch-and-release is only rarely practiced in Venice. The Koreans, who congregate mid-pier, carry their fish home to fry with hot pepper threads or to chop into soup: the Russians, who mix—sometimes uncomfortably—with Rojas crew at the pier end, salt the sardines they get to be dried on a roof on a hot, sunshiny day and the Mexicans often cook their catches right on the pier. For those who don’t fish for keeps, or for those whose haul exceeds the limits of their bellies, an old, dumpling-faced Russian woman in a babushka takes up the slack. Every other day or so, at 3 PM, she wanders from fisherman to fisherman offering 33, and always $3, for a herring, surfperch, or white croaker. Her money is in variably refused by the regulars—even the homeless fishermen wave it away as they hand over one of these—or if she’s lucky, a mackerel or halibut.

The Dark Side

For the most part, the Venice Pier is like that—laid-back, generous, grimy but good-hearted—though sometimes, after dark, and especially when it’s crowded, things are not so mellow. Venice, which closes at midnight, is one of the few L.A. pier that isn’t open 24 hours a day, allegedly due to a not-so-recent shooting in the parking lot. Several years back, up the coast on the Newport Beach Pier, a 60-year-old fisherman tangled lines with an 18-year-old, and when the younger man cut the other’s line, a fight broke out. After some shouting, and after each man had thrown the other’s rod over the pier railing, the older man pulled a knife and started swinging. When the younger man disarmed him and tossed the knife to the sea, the older man grabbed someone else’s fishing rod and started lunging with that. “At some point,” the police later said, “they ran out of weapons.”

Crossed lines can sour the camaraderie in Venice as elsewhere, but ethnic differences can also chafe. One afternoon I watched a Mexican man strike up a conversation with a pair of old Armenians on the subject of tomatoes, which the Armenians were eating like apples. When the old men exchanged words in Armenian, the Mexican narrowed his eyes, huffed, and said, “I don’t know what you said but it was about me so I’m gonna walk away.” The old men shrugged lazily to one another and returned to their tomatoes.

Party Time

Differences melt away, however, when the fishing is good—when the devil, as Stephen Penn might put it, is looking the other way. “In the busy time,” a fisherman named John Halimi told me, “you’ll see to fish coming up per minute.” Another Venice angler put it this way: “Sometimes it’s like flipping a switch. And then—then it’s a party.” Passing schools of bonito can flip that switch, and when they show up, the Venice Pier all but explodes. So too with mackerel—a “mac attack, not an uncommon experience, is the stuff of pier fishermen’s dreams. Halibut, however, are by far the most prized fish here, and a number of fishermen focus solely on them, slowly dragging a live anchovy along the bottom and waiting for the halibut’s soft-mouthed strike-hoping like hell they’ll nab a “barn door,” slang for an ultrarare (around piers, anyway) jumbo halibut clocking in at 30-plus pounds.

Ken Jones, in his encyclopedic-and-then-some guidebook, Pier Fishing in California, determined that the all-time California pier-fishing record belongs to a man named R.A. Hendricks, who caught a 453-pound black sea bass from Stearns Wharf in Santa Barbara in 1925. After a two-hour battle, Hendricks leaped into a rowboat alongside the wharf and dispatched the mammoth fish with a 22 rifle. A sepia-colored rumor has it that a 600-pound sea bass was caught in 1929 at the Manhattan Beach Pier, a few miles south of Venice, but Jones has never been able to verify it. “The old-timers say it used to be like that,” an angler named Greg Wolthausen told me. “They say there used to be so many fish here that if you jumped off the pier you’d break your neck on them.”

Talk like that—about old-timers, legendary fish, the theory and practice of using a Lucky Lura for jack mackerel, etc.—can almost make you forget where you’re standing. A brief glance behind you, however, and you’re instantly reminded: This is L.A., baby. The beaches are thronged with sunbathers, and aspiring starlets brown themselves in the sun.

Yet life on the pier seems removed from all that, as if L.A. stops at the water’s edge and another, truer world begins. It’s a world familiar to anyone who fishes, and while the fishermen of the Venice Pier may differ from their counterparts on, say, a trout stream, or their more ambitious brethren out trolling in the blue water, they sound much the same when they talk about their fishing. “You know.” John Halimi told me, as he punctured a sardine with a No. 2 hook and then cast it out toward the horizon, “I can either stay home and watch TV, or I can come out here. And when I come out here, whether I catch a big fish or a little fish or no fish at all, I feel the same. I feel better.”

_You can find the complete F&S Classics series here

._ Or _read more F&S+

stories._