I HAD HOPED to go to British Columbia this fall, to throw a fly for steelhead

in the Morice River where it winds out of the Telkwa Range near Smithers. I settled for a blue-ribbon trout river in Montana, one that was just far enough from home to give me the sense of taking a trip. In size of fish it was a long step down. But in other ways the streams had much in common. Both ran through country as yet untarnished by the hand of man. And both rivers, by the third week in October, had been handed back to the geese, the bears, and the otters, to which they rightly belonged.

In deference to the size of the fish, I brought only one rod, a 7 1/2-foot bamboo I had built out of cane that I picked up in Scotland some years ago. It handled a 4-weight double taper on its languid, parabolic flex, and I occasionally abused it with a high-density shooting head and the small marabou streamers to which the trout of this river have become so addicted.

For me this was a homecoming of sorts. I had fished the river every fall for a half-dozen years in the late 1970s and early ’80s, pitching my tent on a bluff above the junction of two feeder streams that merged in looping, cobalt meanders through the buffalo grass. Up in the canyon folds above the river, the bugles of elk rose with the season, and more than once I had blackened my face with ash and taken a bow and a quiver of arrows to hunt for their source. But I was older now and damped the heartbeat that quickened to this sound. I had become content to seek a more contemplative sport.

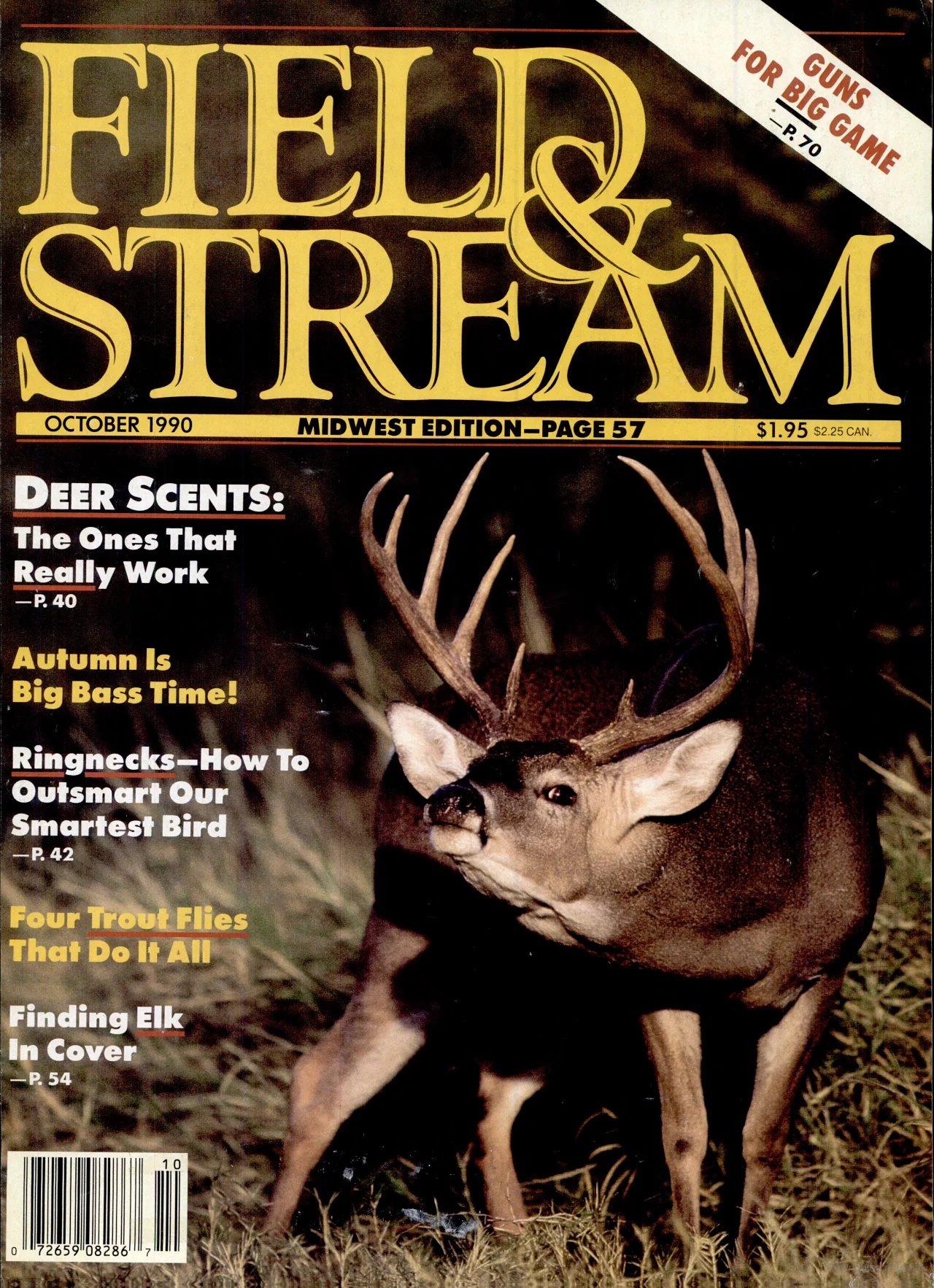

The October 1990 issue featured a mixed bag of the best of fall, and a cover photo by William S. Lea. Field & Stream

It is not a secret, really, this stream in the fall. But the anglers who are lured by its reputation all go to the same places, many miles downstream, where the river coils its way toward the long arm of a reservoir. Most do not suspect that the trout from the reservoir, which migrate upstream to spawn, ever climb much higher than the lower bends of the river. Nor do they concern themselves with any but the heavy-spotted browns about which so many words have been written.

But the secret of this stream is up here in the pines, where the brown trout give gradual ground to an advance guard of rainbows which work their way out of the lake in September. Unlike their more somber cousins, the rainbows do not pause in their march upstream, but swim right through the canyon and beyond. I have seen them jumping like salmon up the waterfalls of the creek that whispers us to sleep at night, but the best fishing is in the several miles of stream below camp. Fisheries biologists have told me that these trout do not spawn until February. So in their migration pattern they are little different from the fall-run steelhead of the Morice that I wanted to catch, and they possess all the qualities of those fish in a smaller package. Hard hitting, high jumping, long winded—they are all that a wild trout should be.

For several years now I have worried that their numbers were declining. In the past I had caught 10 rainbows for every brown in these reaches, but the last couple of autumns the opposite had been true, and while the browns were nice fish, they were not the measure of these rainbow trout in anything but size.

It was evening before my tent was up and the rod assembled. It was nearly dark before the first trout came to hand, a small, silvery brown that I gently unhooked and sent back to its cradle. I folded my arms and stuck my fly rod

in the crook of an elbow. It was not a good beginning. Always before there had been fish in the canyon by the time the baseball pennant races were decided in September. The first pitch of the World Series would be thrown tonight. There had been plenty of time for the run to have come this far. I walked back up the hill and built a fire, cooked a pizza in a pie iron, and tuned my transistor radio to the broadcast from Oakland. This, too, had always been part of the fall ritual, along with the trout and the bugling elk. But tonight even the elk were silent. A handful of coyotes wailed from the rimrock thickets. I folded my waders and boots under the eave of the tent and went to bed.

Sometime during the night I awoke, and for a while I laid there thinking of the problems of my civilized life; worrying about money. It was my first night on the river and I knew that this would pass. I would sleep more soundly tomorrow, and by the third morning all of my life would be right here, and all the gold I’d ever need would have been scattered on the ground by the wind in the aspens.

Morning to a serious trout fisherman comes early. I was up before six, had my lantern lit, and struck for the river with my waders over my arm. During the night they had frozen as stiff as cardboard, and I thawed them in the thin water at the edge of the stream while I tied an olive marabou to the tippet of my leader. In autumns past it had been a spruce fly or a black marabou. Only during the odd year did the color matter. One fall, a run of rainbow/cutthroat hybrids climbed into the canyon. They had wanted orange in the wings of the streamer, and I caught many of them on a fly that was the color of the slits underneath their jaws.

But usually all that counted was being early on the water. When I closed the valve on the lantern it was still dark. The grass was silvered with frost, and the river, a black ribbon with a thin trail of smoke over its surface, burbled peacefully in its sleep. This was the heartbeat of the river that few noticed, for the sound seemed to disappear with the daylight.

I waded out a few feet and began to saw the shooting head through the guides, casting a little upstream and working the marabou back in short pulses across the current. I took a step downstream and cast again. No strikes came but I was still too high in the riffle. In a strange way I dreaded my steady advance toward the deeper part of the run where the rainbows ought to be, where they had always held in the past. If they weren’t there, I didn’t really want to know. But then the fly was working down, cutting its curves into the tongue of the first thick water, and here it was, the hard pull of a good trout. I knew it was a rainbow even before it jumped. It ran its heart out for the next 5 minutes and then I had it in hand, an 18-inch male with the beginning of a kype on the lower jaw. Its gills flared in the water for a time before it was strong enough to go.

I took three more rainbows in the next half hour. All of them were better than 15 inches, and all of them held a bend in the bamboo for such a long time that I had to dip the rod in the water to keep ice from forming in the snake guides. I finished out the run with a beautifully spotted brown trout with orange pectorals and a belly the color of old gold. I slipped the marabou into the keeper ring, satisfied, and watched a pair of geese whistle overhead as they headed upstream.

I could have kept on fishing. There are a dozen good pools and riffles in this stretch of the river. I used to race madly from one to the next in a set sequence, steadily retreating into the deeper shadows, because once the sun hit the surface the trout became shy.

But on this morning I was content to go no further. Just knowing that the fish were back was enough. I sometimes wonder if our biologists, in their endless tinkering with the stocking programs of the reservoir that produces these fish, and of other reservoirs in the West, fully realize the jewel they have in an autumn run of rainbow trout. They are a poor man’s steelhead, and catching them was as close to fishing in British Columbia as I would get this fall.

As I turned from the river, I found my eyes wandering up among the thickets where the elk lived. I knew their silence had only been suspense, and that a one would bugle any minute now.

_You can find the complete F&S Classics series here

._ Or _read more F&S+

stories._