For most anglers it all starts with some species of sunfish. At some point, Dad or Grandad handed us a rod with a bobber and worm

at a local creek or lake, and the fishing addiction began. The funny thing is that many anglers “graduate” over time, often forgetting about the simple joy of catching types of sunfish family until they have little kids of their own and want to pass the torch.

The reality is that sunfish are fun and challenging no matter how old you are or skilled you are as a fisherman. They’re readily available to almost everyone in the country, though ironically all the members of the sunfish family tend to be lumped together and simply called “sunfish” or “bluegills.” Both are technically incorrect. There are many species of distinct sunfish in the U.S., some existing in very small areas, and they all offer different challenges and reasons to visit different kinds of water. Here’s a breakdown of the most common and popular sunfishes in America. And it’s almost a guarantee that at least one of these types of sunfish is swimming less than a few miles from your house.

Table of Contents: Types of Sunfish

Bluegill

Redear Sunfish

Pumpkinseed Sunfish

Redbreast Sunfish

Longear Sunfish

Green Sunfish

Rock Bass

Warmouth

Bluegill

This big bluegill smashed a small popper on a pond. Colin Kearns

World Record: 4 pounds, 12 ounces

Identifying Marks: Bluegills have a powder blue gill cover. Females have a yellow breast, while the males have a bright orange to copper colored breast. Both males and females have all-black ear flaps and a black blotch on the lower rear portion of their dorsal fins, which other sunfishes do not have. Bluegills can also exhibit vertical barring on their sides.

The Most Powerful Type of Sunfish

are one of the most ubiquitous types of sunfish in the United States. Though originally native to just the eastern half of the country and portions of Northeastern Mexico, they have been implanted in almost every corner of the Lower 48 barring some high-mountain regions. While the average bluegill measures 6 to 9 inches, these fish have more potential to reach above average size. The current 4-pound, 12-ounce world record

caught in Alabama has held since 1950, though certain bodies of water are famous for routinely producing bluegills that weigh more than a pound.

Bluegills—large ones especially—are tenacious. Of all the types of sunfish it’s hard to argue that bluegills aren’t the most powerful. When caught on a light-tackle rod that allows their strength to shine, they are an absolute blast to reel in. (Looking for a new bluegill rod? Check out our reviews of the best fishing rods

of the year.) Like all sunfish, they primarily feed on insects, tiny baitfish, and little crustaceans. While a simple garden worm hanging under a bobber will nab you piles of bluegills, obsessed panfishermen hunting for heavy-weight specimens often employ tactics designed to weed out the littler fish. By casting jigs

, spinners

, and small crankbaits

that are a little too big for undersized bluegills, they increase the likelihood that only the biggest and most aggressive fish in the area will take the shot.

when water temperatures hover around 80 degrees, and they largely shutdown when the temperature dips below 50 degrees. Though they can be caught through the ice in winter, success usually hinges on finding a thermocline where the water temperature below remains favorable, or fishing early in the ice season before the water below the surface gets too chilly. While bluegills can thrive in slow-moving portions of rivers and streams, they don’t love current. A clear lake or pond with plenty of aquatic vegetation and access to deep water is the ideal habitat for growing trophy-class bluegills. They can also tolerate a mild amount of salinity, making it possible to find them within some brackish water estuaries.

Redear Sunfish

Redears commonly feed on the bottom and in deeper water than other types of sunfish. Adobe Photostock

World Record: 6 pounds, 4 ounces

Identifying Marks: Redears, a type of sunfish, get their name from the bright red to orange outer edge of their black ear flaps. This colored border is wider on males than females. Their overall body tone ranges from olive green to gold, and the breasts of both males and females range from vivid yellow to orange.

Across much of the South, redear sunfish are known as “shellcrackers.” The name stems from a unique set of teeth positioned farther back in their throats that are specially designed to crack the tiny aquatic snails they love to eat. While snails make up a large portion of the redear’s diet, they also feed on insect larvae and small baitfish. What sets them apart from most other types of sunfish, however, is their propensity to feed on or close to the bottom and gravitate to deeper water.

During the summer, redears will move as deep as 35 feet seeking cooler water. In bodies of water with less depth, they gravitate to shady areas and thrive around submerged stumps, root balls, and in isolated clusters of very dense weeds. Like bluegills, they prefer clear, still water as opposed to moving water, and they become largely inactive when the water temperature falls below 50 degrees.

One of the Biggest Types of Sunfish

Redears are native to the southeastern portion of the United States. They have also been implanted in many other areas throughout the West and Midwest, though they are still far less ubiquitous than bluegills. They do, however, have the potential to grow bigger than bluegills. Lake Havasu, on the border of Arizona and California, is renowned for its giant redears, boasting the current gargantuan world-record fish that weighed 6 pounds, 4 ounces. (Want a new fishing reel with a strong drag? Check out our round of the year’s best fishing reels

.) It was caught in 2021, and many panfish enthusiasts believe Havasu has the potential to kick out an even bigger specimen. The average redear you’re most likely to bump into at your local lake or pond, of course, will measure between 7 and 10 inches, but Lake Havasu provides proof of redear growth potential in an ideal habitat.

Another reason why redears grow big is because they produce fewer young than other members of the sunfish family. This means they are less likely to overpopulate a body of water, which often results in stunted fish. Subsequently, redears also grow much faster than other sunfishes.

Pumpkinseed Sunfish

Pumpkinseeds are covered in stunning colors. Adobe Photostock

World Record: 1 pound, 8 ounces

Identifying Marks: The base color of a pumpkinseed’s body is gold or copper, but their flanks are speckled with vivid red, orange, and green flecks. They have a fiery red-orange belly, and their fins, sides, and gill plates also feature iridescent blue-green accents reminiscent of a tropical saltwater fish, making them arguably the prettiest member of the sunfish family.

One of the Most Common Types of Sunfish

Pumpkinseeds are often referred to as “common sunfish,” largely because they are so widely available. While native to the north-central and eastern half of the country, pumpkinseeds prefer slightly cooler water temperatures than other sunfishes, helping them to thrive well into Canada and across the Northwestern portion of the U.S. where they’ve been stocked.

Aside from being so readily available to many anglers, pumpkinseeds also prefer shallow water, rarely venturing into deep, open expanses of large lakes. Because of this love of the shallows, it’s pumpkinseeds you’re most likely to find in park ponds, drainage ditches, and slow-moving creeks that are less desirable to or prohibitive of larger gamefish species. As pumpkinseeds gravitate to the edges of water bodies, they are the most likely culprit to steal your worm if you simply choose a random piece of bank and make a short cast. Pumpkinseeds also do well in heavy weeds and algae, whereas redears and bluegills don’t like it when the vegetations grows thick enough to choke out and deoxygenated portions of the lake or pond.

Between their love of cooler water and shallow water, pumpkinseeds don’t quite have the growth potential of other sunfishes. The average fish falls between 5 and 7 inches, and any pumpkinseed measuring more than 8 inches is considered a trophy.

Redbreast Sunfish

This jumbo redbreast sunfish hit a soft plastic swimbait. Joe Cermele

World Record: 1 pound, 12 ounces

Identifying Marks: As their name suggests, redbreasts have a vivid red-orange to yellow breast that extends across their bellies to the anal fin. Blue streaks and faint red dots cover their gold to brown sides, and their black ear flaps do not have a light-colored leading edge.

Sometimes referred to as “yellowbellies,” redbreast sunfish are native to the entire East Coast from Maine to Florida. They have, however, been implanted inland as far west as Tennessee, as well as across the South and throughout the state of Texas. A key characteristic of redbreasts is that, unlike other types of sunfish, they’re equally happy in moving water as they are in still water. Within their range they’re commonly found in rocky streams and creeks with ample flow, as well as in larger river systems.

While they don’t prefer to hold directly in fast current, they’ll pile into eddies, seams, behind larger boulders and laydowns, and around bridge abutments. In lakes and ponds, redbreasts gravitate to weedy areas with a sandy or muddy bottom where they can feed on insects, snails, and small baitfish. Redbreasts are also more prone to feeding after dark, which is not a characteristic of other sunfishes.

While the average redbreast measures around 6 inches, they will occasionally grow larger. All types of sunfish school up during certain times of the year, but redbreast tend to school year-round, so where you find one, you’ll find a bunch.

Longear Sunfish

Longears don’t get very big—but they’re very pretty, and they are eager to strike poppers. Adobe Photostock

World Record: 1 pound, 12 ounces

Identifying Marks: The sides of a longear sunfish are mottled in iridescent orange and turquoise spots. Vivid turquoise streaks also adorn their cheeks and gill plates. The base color of their backs is typically olive green, and their breast color can range from pale red to pale yellow. Their black ear flaps feature a red or yellow edge, and while this flap is no longer than that of other sunfish, their extended gill cover makes the flap appear much lengthier and set farther back on the body, hence their name.

One of the Most Colorful Types of Sunfish

The range of the longear straggles as far north as New York, moving diagonally through much of the eastern Midwest and into Texas. Though they can be caught in many southern states, they are not as prevalent in coastal states. From Georgia to New Jersey, longears are in shorter supply. They’re also shorter in stature. The average adult longear tapes out at a mere 5 inches, but what they lack in size they make up for in sheer beauty and eagerness to eat worms and crickets.

Longears get on just fine in bodies of still water, though they truly thrive in slack water areas of clear streams. Like pumpkinseeds, longears prefer shallow water, however, unlike most other sunfish, vegetation is not a requirement. Longears are happy to feed across barren gravel, sand, rock, and mud flats, as these areas provide more opportunity for these tiny fish to root for micro insect larvae and crustaceans. Longears also love to feed on surface insects, making them a great target for fly anglers.

Green Sunfish

Green sunfish will aggressively strike worms, jigs, or poppers. Joe Cermele

World Record: 2 pounds, 2 ounces

Identifying Marks: Green sunfish have a far more elongated body than other types of sunfish, resembling a bass more than a bluegill or redear. They also have a noticeably larger mouth than other sunfish. Their bodies are primarily olive or brown in color with a bit of emerald spotting on their sides and emerald or light blue streaks around their mouths. Their bellies are typically light yellow or white.

The native range of the green sunfish extended roughly from Pennsylvania west across the entire lower 48. However, over the last few decades, green sunfish have been rapidly expanding their range deeper into the Northeast and South, which creates an issue.

The Most Aggressive Type of Sunfish

Hands down, green sunfish are the most aggressive members of the family. You could even say they’re bullies, as they’re so territorial that they can cause populations of other native species to decline when they find their way into waters where they didn’t formerly exist. Given their large mouths, they can eat much bigger foods like crayfish and shad. That big mouth can also swallow juvenile gamefish, which is bad news considering they proliferate easily. Furthermore, “greenies” are tough as nails. They can survive and thrive in murky water, water with low oxygen levels, and areas that are heavily weed choked. They can also withstand a wide range of water temperatures.

On the plus side, green sunfish are extremely fun to catch. Many people confuse them with a hybrid between a bluegill and smallmouth bass considering they will live and hunt in heavier current than other sunfish. They’ll happily take a worm under a bobber, but spinners, jigs, and even poppers work well since they eat larger prey. The average greenie will only measure 6 inches, so make sure to use a rod light enough to highlight their strength.

Rock Bass

Rock bass are a great species to target when fishing with kids. Joe Cermele

World Record: 3 pounds

Identifying Marks: Rock bass have a larger mouth than other sunfishes. Their body color is gold to brown with areas of black spots and mottled black patches similar to a crappie’s pattering. Their bellies are white or light yellow, but their most striking characteristic is their blood-red eyes.

Sometimes referred to as “goggle eyes” or “redeyes,” rock bass don’t exactly get much love in the angling world. They’re not as delicious in the pan as other sunfishes, reported to have a mushier, blander flesh. They also draw ire because they have large mouths, which means they’ll take shots at large lures and flies intended for species like walleyes, smallmouth bass, and trout. But if you chase after them specifically with a nice, light rod, they’re an absolute blast, especially when you’re wet wading a creek in the summer with the kids.

Even though the average adult rock bass will only measure around 9 inches, they routinely break the 1-pound mark, especially in large, rocky bodies of water like Lake Erie. Though they can be found in reservoirs and smaller lakes, rock bass thrive in moving water, especially streams with lots of hard bottom and chunky rocks. While native to the Midwest and Upper Midwest, rock bass have expanded their range well east into the mountains of Virginia and the Carolinas, and a far north as Southern Maine.

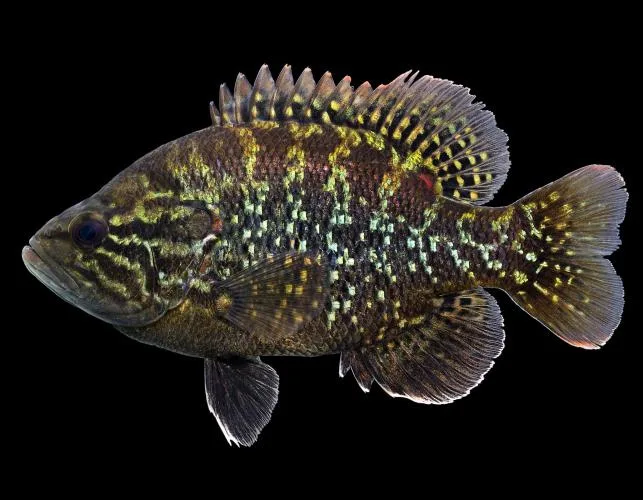

Warmouth

Warmouths are commonly found in swamps or backwaters. Missouri Department of Conservation

World Record: 2 pounds, 7 ounces

Identifying Marks: Warmouths

have red eyes, mouths larger than other types of sunfish, as well as an extended lower jaw. Their bodies are typical brown to copper in color with darker brown mottling and faint light blue to white spots mixed in. Warmouths also have several reddish-brown streaks that radiate from the eye and extended across their gill plates.

Warmouths tend to have low reproduction rates, which is why they’re not as widespread across the country as other sunfishes. Though they have been stocked in parts of the west and south through Texas, their stronghold remains in the southeastern portion of the U.S. They can live in any type of water body, but their preference is swamps, backwaters, sloughs, and weedy bays. They can also survive in water that’s too stagnant to support other members of the sunfish family.

Because of their red eyes and dark bodies, they are often confused with rock bass, which have a much broader range. The easiest way to tell them apart is that the warmouth has only three spines on its anal fin while a rock bass has six. An adult warmouth averages 7 inches in length.