_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

All of Primos game calls are produced in a factory in Brookhaven, Miss.

Anthony Foster plays the guitar. A Taylor Koa leans on a stand in the corner of his office at Primos Game Calls in Brookhaven, Miss., but it’s not the only instrument in the room. His desk is covered with turkey calls. The Brookhaven site produces all of Primos’s wood and acrylic game calls, and any given day Foster and his team may churn out 600 predator calls, 2,500 deer grunts, 700 turkey pots, and a small run of elk or crow calls. “We’re a CNC plant that never took away from the craftsmanship,” Foster tells me. “You wouldn’t know it from the outside, but there’s millions of dollars in machinery here.”

Turkey calls are piled on Anthony Foster’s desk. Michael R. Shea

Consider box calls alone: Brookhaven can pump out 2,500 to 3,000 of them a week. The flow of production is staggered, but it takes about three hours of machine time, hand-finishing, and tuning to turn two blocks of wood into the product that fits inside your turkey vest. This is a place where high-throughput manufacturing intersects with human hands.

Primos cranks out thousands of box calls every week. Michael R. Shea

Foster’s family was in the wood cabinetry business. He made his first turkey call when he was 11 years old, mimicking a scratch box his grandfather cooked up decades before. He studied computer-numerical-control (CNC) machining in school, and shortly thereafter the family business picked up commercial account—doing all of the cabinetry for large hotel chains throughout the south. A lifelong turkey hunter, Foster started turning out his own calls—a side-gig that went on to become so profitable that he made it his main business as White Feather Game Calls.

Foster made calls for all of the big manufacturers. He worked up designs, produced the calls, then stamped other company’s logos on the box, including Primos, who he subcontracted for years. Several call companies offered to buy White Feather, and one of them offered Foster a hell of a deal. He broke the news to Will Primos.

“Will told me to hang-on one quick second,” Foster remembers. “He proposed taking care of all the paperwork, human resources, insurance, benefits. ‘We’ll free you up to do what you love,’ he told me. I liked the sound of that. I wanted to just design and build calls.”

Lumber for thousands of future turkey calls awaits. Michael R. Shea

On Foster’s desk there are two dozen different calls in various stages of design. He’s responsible for making the innovative Heart Breaker, which made box calls easier to use. He was the first to put a thumbhole on a box call; same goes for the magnetic lid. And he was the first to rout a turkey call on a router, use a laser engraver, and a 3D printer. “This is my hobby and my job,” he told me. Now he’s working on a slate call that automatically rolls the note over. “Every call is a musical instrument. My job is to make it sound better, and easier to play.”

A super-duty lathe cranks out turkey strikers in minutes.

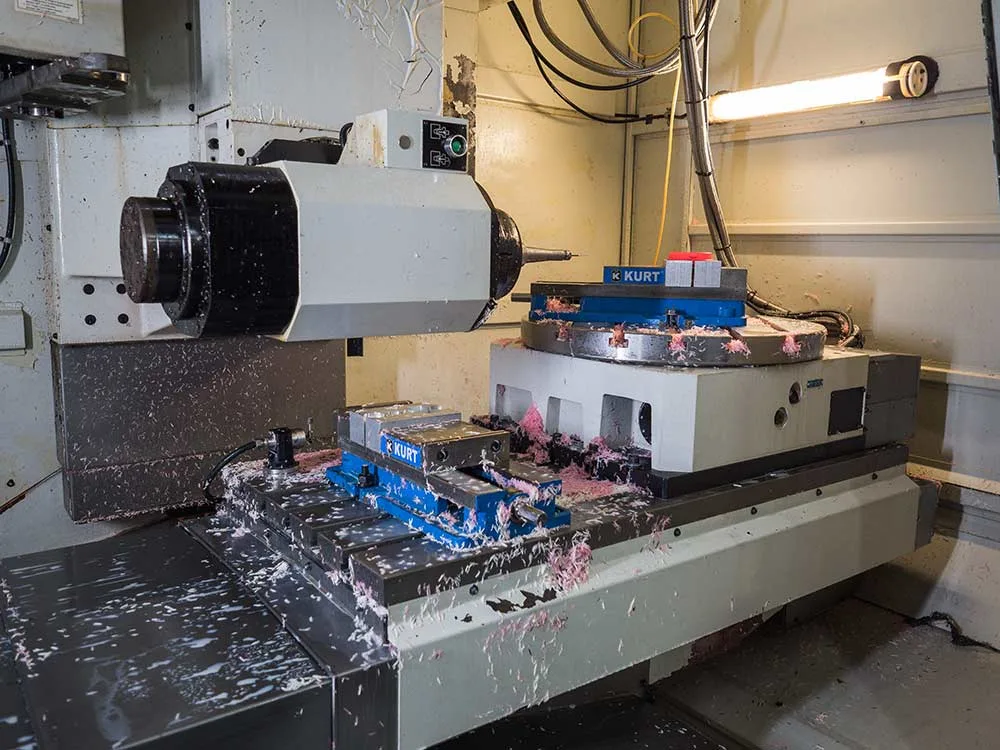

Step into the Brookhaven facility, you see machines before you see any calls. A Hurco prototyping machine that looks like something from 2001: A Space Odyssey sits next to a large 3D printer. At a nearby computer, Randy Kennedy worked on a computer-aided-design (CAD) drawing of a Hensanity version 2.0 turkey pot, which has holes cut into the sides that let the turkey hunter cover them up with his or her fingers to make different notes. With a few keystrokes, the big Hurco began to spin and form a lump of pink polycarbonate until was cut down into a turkey pot.

An employee works on a new design for a Hensanity turkey pot call. Michael R. Shea

Here, a prototyping machine trims a chunk of pink polycarbonate into a pot call. Michael R. Shea

Across the room, a Haas SL30 Lathe, turned four-foot wooden dowels into a pile of strikers in no time. The wood for the striker, and all the rest of the call materials, are stored in a lofted metal building out back. More than 40 different materials are in stacks across. Several different flats of lumber for box calls are on one side, including purple heartwood. Primos was the first to use it in a production box call. The sound was so good that everyone uses it now. They were also the first to use canary wood. “It’s not about building a pretty call,” Foster says. “We don’t have the fancy decorated lids or striped and colored woods, but we don’t sacrifice on the sound.”

Purple heartwood, which will be used for box calls, makes a fantastic turkey sound.

Purple heartwood, which will be used for box calls, makes a fantastic turkey sound. Michael R. Shea

On the back wall, acrylic dowels are stacked for future duck and goose calls. Foster and call builder Jerry Cox were the first people to use a CNC machine to turn acrylics; now it’s the industry standard.

These crylic dowels will be used to produce waterfowl calls. Michael R. Shea

Back on the main floor, more calls are being made. A CNC machine cuts a run of Jackpot cups. Ten yards away, a C.R. Onsrud router pushes through a run of custom boxes for an upcoming NWTF project. CNC is a computer-controlled process: Drawings are fed to the machine, which then cuts at the material to the exact specifications of the drawing. Foster was among the very first CNC operators in the country to cut turkey calls, if not the first. The advantage is that every call comes off the line identical to the next—in look and sound—but they’re not yet ready for the woods. They need to be hand-finished and tuned.

A router cranks out a run of custom box calls for the National Wild Turkey Federation. Michael R. Shea

A CNC machine produces a batch of Jackpot cups. Michael R. Shea

Every call in the Brookhaven facility requires human attention, but on the day I visited, it was surprisingly empty. When I asked Foster about all the empty stations, he laughed. “It’s a Friday during turkey season.” But there were still enough people there to put the finishing touches on some calls. One employee ran a belt sander on a call until all of the sharp edges and chambers were rounded and smoothed. The final step in a turkey call is the tuning process, which, no surprise, is done by hand—and ear.

Foster’s design principles, and in turn the Primos philosophy, comes down to simplicity. “There’s this perception that calling is hard,” he tells me. “We don’t want that. Calling should come easy because it’s so hard for many people to get outdoors, to get hunting. You shouldn’t jeopardize that experience because a call is hard to work.” To that end, they cull thousands of dollars in wood every year. Next to employee Dennis Mason, who tunes the calls, sat a pile of half a dozen box calls—calls that made it all the way to last step of the process, but don’t sound quite good enough. They’re destined for the trash bin.

On a Friday during turkey season, it’s no surprise that many employees are out hunting. Michael R. Shea

“Lots of things can go wrong on a hunt,” Foster tells me. “If the calls are one of them, I’ve failed. If my product is on a guy’s first turkey hunt with his son, a guy’s first elk hunt out in Colorado—he paid big bucks to get there. We’re there to help make that hunt successful, make that experience successful. That keeps me motivated to ensure we’re always building the best.”

Around 4 p.m. the Brookhaven site started clearing out. Foster and I stood in the laser shop where Primos does all its wood engraving in-house. They’re working up plans for a custom engraving program that they hope to launch later this year. The laser itself is hypnotizing, darting back and forth, cutting an image line-by-line like a space-age Etch A Sketch.

A laser cutter races through the artwork on the lids of box calls.

Most employees filtered out the door, eager for a jump on their weekend, whether it meant a cookout or a turkey hunt or both. I asked Foster what he was up to. “We’ll hunt the morning, but right now I’m going to stick around and fiddle with my guitar.”