Duck hunting in America has a complicated history. The market gunning era of the late 1800s depleted waterfowl populations to dangerous numbers. And over the first half of the 20th century, it was duck and goose hunters who recognized something needed to change if waterfowling was to continue across the continent. Those are the types of hunters you’ll find on this list. People who helped conserve, protect, and advance waterfowling to what we now know it to be today.

You’ll also see a range of decoy carvers, call makers, shooting experts, boat builders, and writers who changed how we hunt ducks and geese. Every waterfowler highlighted below either influenced the way we hunt or had an impact on waterfowl and wetlands conservation. Without them, duck and goose hunting wouldn't be the same. Here are the 25 greatest waterfowl hunters of all time.

1. Fred Allen

Before Fred Allen got to work, duck calls looked like half of a modern call. The old tongue pincher-style calls had no barrel and, therefore, no mouthpiece. Allen’s call had a single reed, a flat tone board, and a barrel that not only gave you a mouthpiece to blow into, but a resonance chamber, too.

Allen, of Monmouth, Illinois, first advertised his calls in 1880, making his calls among the first to be sold commercially. The ads claimed the calls had been available since 1863. He also marketed duck calls for performers who needed sound effects, claiming that his calls, in addition to making duck sounds, “Can be used for hen cackles, rooster crows, pig grunts, and many other sounds.”

Allen was market hunting in 1880, but soon opened the Allen Duck Caller Company, where he sold his calls and oars of his own design, which allowed you to row a boat while facing forward. In 1892, he redesigned his calls, and the new barrels included that familiar lanyard groove you see in the barrel of every modern duck call. After he gave up market hunting, Allen maintained a duck camp in the Monmouth area for many years. —Phil Bourjaily

2. Hazelton Seaman

In 1836, Hazelton Seaman created a duck boat so revolutionary that the design is still used today, over 180 years later. During the 19th century, salt marshes up and down the East Coast wintered massive flocks of waterfowl, making excellent hunting for those willing to venture out into the bays. At the time, most hunting boats featured an open deck and a flat bottom. Seaman designed a small 12-foot rounded bottom boat with an enclosed deck. He named it the Barnegat Bay Sneakbox.

The rounded bottom made the boat more seaworthy and easier to row. He also included a centerboard and a sail for faster navigation. The boat featured a canvas hood, or "spray shield," attached just forward of the cockpit to protect the hunter from sea spray while navigating. The rounded deck had two main purposes: keeping the inside of the boat dry and making it easier to camouflage in the low profile salt marsh. Seaman also built a hatch that went over the small cockpit to completely enclose and fully waterproof the boat. It is said that hunters would go out for days and enclose themselves in these tiny boats and stuff them with salt hay to keep warm at night. I can't imagine it was very comfortable, but it changed the game for waterfowlers.

The boat's small design allowed hunters to access skinny water creeks, and the low profile kept it hidden in the flat marshes. Seaman even had the sense to incorporate decoy racks to store large numbers of dekes. Once motors were invented in the late 1800s, hunters equipped their sneakboxes with small outboards to make them even more versatile. Over time, the Barnegat Bay Sneakbox evolved, but not by much. I grew up hunting out of a similar one-man grassboat that was based on Seaman's original design. These boats are still very common throughout the bays of Long Island and New Jersey. —Ryan Chelius

3. Ding Darling

It’s not clear how many ducks Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling actually shot in his lifetime. We only know of one bird he harvested, a wood duck he killed as a boy in northwest Iowa. He shot the duck in the spring, and his uncle took him to task for killing a bird during breeding season. The incident was the beginning of Darling’s lifelong interest in waterfowl conservation. As cartoonist for both the Des Moines Register and the New York Herald Tribune, Darling often used his platform to call out over-shooting, habitat destruction, and pollution.

FDR named Darling first to a blue-ribbon panel on wildlife restoration in 1934, then appointed him Director of the Biological Survey, the forerunner of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Following the passage of the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act in 1934, Darling was chosen as the artist to design the first stamp, which shows a pair of mallards landing in a wetland.

As chief of the Biological Survey, Darling was frustrated by a congress that would not fund his conservation projects. He resigned in 1935 and helped found the National Wildlife Federation in 1936. NWF remains the nation’s largest non-profit conservation group. —P.B.

4. Nash Buckingham

In August of 1920, a lanky and athletic Memphis sporting goods store owner and part-time sports writer named T. Nash Buckingham published a 38-line poem in Field & Stream titled “My Daddy’s Gun.” It was the first contribution of what would become one of the most famous writer-reader relationships in this magazine’s history.

Over the next 35 years, “Mr. Buck” published scores of hunting stories for the magazine, mostly tales of waterfowling and quail hunting. He wrote of goose hunting from pits dug by torchlight into Mississippi sandbars and of quail hunting behind “potlicker bird dogs.” Some of his best-known stories, such as “De Shootinest Gent’man” and “The Neglected Duck Call,” helped fill nine books between 1934 and 1961. The best of them sold out before they arrived in bookstores, and first-edition Buckinghams these days fetch hundreds of dollars.

But it wasn’t just books that caught the fancy of Buckingham fans. In 2002, Buckingham’s 1926 12-gauge A.H. Fox-Burt Becker side-by-side, dubbed “Bo Whoop” for its thunderous report, was found in an Illinois pawn shop after being lost for 64 years. Perhaps the most famous shotgun ever built in America, it brought $300,000 from an anonymous buyer. —T. Edward Nickens

5. Elmer Crowell

Known as one of the greatest decoy carvers of all time, Elmer Crowell spent most of his life observing and hunting waterfowl along the eastern shores of Massachusetts. He started carving decoys as a teenager solely for hunting. In his younger years, he worked as a hunting guide, market gunner, and cranberry farmer. Then, in the early 1900s, when the waterfowl conservation movement started to pick up steam, Crowell turned to carving decoys full-time. He focused on making and selling decorative duck, goose, and shorebird decoys. Though he continued to carve gunning decoys and build duck boats.

Crowell set the standard for decorative carving, and his decoys, many of which now live in Shelburne Museum, are as durable as they are beautiful. He is known for carving and painting extremely realistic-looking wooden dekes, matching the feather patterns, shadings, and postures of real birds. At a time when most gunning decoys weren't much more than a slab of cork, Crowell's elegantly carved wooden decoys were revolutionary. He changed the way hunting decoys looked and was one of the first carvers to recognize a market for decoy collecting. In 2006, one of Crowell's decoys sold for $830,000. —R.C.

6. Fred Kimble

Fred Kimble is responsible for the choke in your shotgun. Born in Illinois in 1846, Kimble hunted commercially on the Illinois River, where competition among market hunters was fierce. To give himself an edge, Kimble worked with a Peoria gunsmith named Charlie Stock, experimenting on tapering the end of a shotgun bore to produce tighter patterns. The result was a 6-gauge single shot that, in Kimble’s capable hands, was an 80-yard gun. He is most associated with a tight-choke 9-gauge single-shot Tonks muzzleloader, with which he made huge bags of ducks and also used to win live pigeon, glass-ball, and clay target championships.

Others were also working on chokes in the 1860s. However, Kimble not only developed an effective pattern of choke-boring, but his fame as a hunter and target shooter popularized choke-bored shotguns. —P.B

7. John Browning

Most waterfowlers over the age of 50 owned or at least used a Browning Auto-5 at some point in their lives. With its innovative recoil operating system and distinctive ‘humpback’ receiver, the A5 is to duck hunting what pumpkins are to Halloween. Built to last, dependable, and easy to maintain, the A5 led the autoloading shotgun market for more than 50 years.

The incredible mind behind this iconic duck gun was John Moses Browning. He designed and built his first firearm at age 13 and went on to patent over 125 additional weapons, including the venerable 1911 pistol, Browning M2 heavy machine gun, and the Browning Automatic Rifle. In 1878, Browning, along with his younger brother, Matthew, founded the Browning Arms Company, now headquartered in Morgan, Utah (originally Ogden).

Browning’s contributions to the waterfowling and upland bird hunting world have been unmatched throughout time. His last completed work, the Browning Superposed, is considered by many as one of the finest O/Us ever made. But it is the A5 that will forever leave its mark on the waterfowl hunting community. —M.D. Johnson

8. Jack Miner

Ontario native Jack Miner banded his first wild duck in 1909 and got a report of one of his birds being shot in South Carolina the next year. He was hooked on the nascent scientific breakthrough and, six years later, began inscribing a Bible verse on the slim aluminum bands he placed on the legs of ducks and geese. Over the next 30 years, Miner would band some 50,000 ducks and 40,000 geese with his one-of-a-kind bands, each one bearing Scripture.

Miner was soon a minor celebrity known as “Wild Goose Jack," and his data was instrumental in early efforts to pass conservation laws. Today, the 400-acre Jack Miner Migratory Bird Foundation continues to educate the public about a man many consider one of the founders of the modern wildlife conservation movement. —T.E.N.

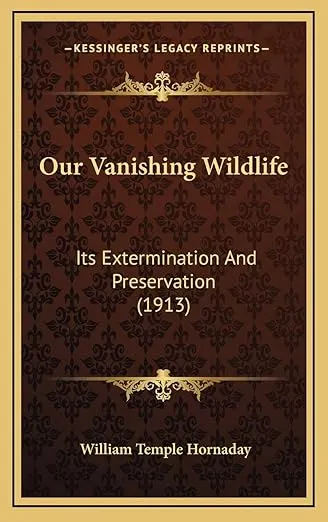

9. William Temple Hornaday

A passionate hunter and taxidermist who rose to acclaim as the first director of the New York Zoological Society, today known as the Bronx Zoo, Hornaday killed the first crocodile recorded in Florida, the first tiger he saw in India, and 43 orangutans in Borneo that he mounted. He was brash and unapologetic. But he is better known for his work to save bison from extinction and advocating for big game conservation. His book Our Vanishing Wild Life had a significant impact on the thinking of conservationists such as Aldo Leopold.

However it was the excesses of market hunting for waterfowl that really got him worked up. As the U.S. was debating what would become the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, Hornaday went on a tear. “We are weary of witnessing the greed, selfishness and cruelty of ‘civilized' man toward the wild creatures of the earth... It is time for a sweeping Reformation, and that is precisely what we now demand.” Currituck County in North Carolina received his focused ire. It was “the bloodiest slaughter-pen for waterfowl that exists anywhere on the Atlantic Coast,” he thundered in print. His make-no-apologies approach helped pass what is the most comprehensive migratory bird protections in history. —T.E.N.

10. John Olin

Although he began work as a chemical engineer in his father’s Western Cartridge Company, John Olin was not just another nepo baby. He would go on to hold 24 patents and become president of the massive Olin Industries. He was also a conservationist and Lab man, and his most famous dog, King Buck, would adorn the Federal Duck Stamp. Most importantly for waterfowlers, he worked hard to improve shotshells. Olin’s Super-X ammunition patterned far better than anything that preceded it.

The story goes that sometime in the 20s, Olin was hunting with a friend who would land ducks and shoot them on the water because his ammunition couldn’t reach them in flight. Water-swatting offended Olin enough that he went to work in the lab on a better duck load. By switching to progressive powders, he developed a shell that could achieve higher velocities without generating dangerous pressures. The new Super-X shells were loaded with hard lead shot to improve patterns and shorten shotstrings. The resulting Super-X (Super Excellent) shells extended the range of a shotgun far beyond anything the competition was loading. In the 1930s, Olin worked with gunmakers Fox and Ithaca to make the first 3-inch 12-gauge and 3 ½-inch 10-gauge magnum shotshells. —P.B.

11. Chick Major

Nowhere is duck calling held in higher regard than in the flooded woods of Arkansas, where timber hunting in its purest form requires nothing than kicking ripples in the water and blowing a single reed. Darce Manning Major, known universally as “Chick,” began making duck calls in the 1930s in Conway, Arkansas. After he married Sophie Ward, the couple moved to Stuttgart and set up shop. Major won the 1945 World’s Championship with his Dixie Mallard call. It would be one of 28 World Championships won by Major, Sophie, step-daughter Dixie Holt, son-in-law Eddie Holt, and stepdaughters Brenda Cahill and Pat Peacock. Peacock was the only woman ever to win the Men’s Worlds, which she won twice, then added a Champion of Champions title.

The Majors were called “the World Champion Duck Calling Family” in the '50s and '60s. “We were the original ‘Duck Dynasty,’” Dixie Holt would say. An unofficial member of the family, young Butch Richenback hung out at Major’s shop, first sweeping floors, then graduating to tuning calls. Out of respect for Major, Richenback waited until after his mentor’s death in the '70s to found his famous Rich-N-Tone call company. —P.B.

12. Joseph Knapp

On a remote spit of marsh and pinewoods that juts out like a bony knuckle into North Carolina’s famed Currituck Sound, Joseph Knapp, a New York publisher and philanthropist, hatched an idea. It was for an organization based on what was then a pioneering concept: Instead of merely conserving wildlife through regulation, scientific principles of propagation and conservation could actually increase the number of animals on the landscape. At Knapp’s palatial 11-bedroom hunting estate on the southern tip of Knotts Island, he formed the More Game Birds in America Foundation.

Incorporated on October 6, 1930, in the throes of the Great Depression, Knapp’s organization would take over management of America’s first school for gamekeepers—the Game Conservation Institute. The group would even pull off the first international waterfowl population survey by flight, the 1935 International Wild Duck Census. The group was eventually hammered by the economic woes of the period, and in 1936, More Game Birds in America shifted its resources and assets to a brand-new and even more visionary effort: The 1937 founding of an organization called Ducks Unlimited. —T.E.N.

13. James Ford Bell

Some might think that James Ford Bell’s finest gift to the world was Cheerios, which Bell introduced while serving as founder and CEO of General Mills. And indeed, Bell’s creative and philanthropic streak was wide. During World War I, the Minnesotan helped run the military effort to keep flour shipments to the war effort strong, and Bell was a critical leader in the post-war European Hunger Relief Mission.

But Bell was also a serious waterfowler, and his impact on ducking and goosing in North America just might overshadow the breakfast cereals. Concerned about duck populations, he started a program at his duck club on the famed Delta Marsh of Manitoba that involved saving two ducks for each one shot. Collaborating with Aldo Leopold, Bell ultimately founded the Delta Waterfowl Foundation, parent to today’s highly active conservation group Delta Waterfowl. —T.E.N.

14. Tom Roster

Every duck hunter has an opinion on shot size and velocity, but the truth is out there, and Tom Roster found it. Roster has shot ducks and geese in the field in the name of science for 50 years. He has patterned thousands of shotshells and conducted double-blind tests with volunteer hunters, observers, and rangefinders to study the difference between shells and shot materials. The result is a massive database comprising over 28,000 necropsies of ducks and geese that settles the argument—whether you like answers or not—about shot size, material and choke, and what it actually takes to cleanly kill a bird.

Roster began as the Ballistics Research Director with the Oregon Institute of Technology, then worked with the USFWS, and then with the Cooperative North American Shotgunning Education Program (CONSEP), a consortium of U.S., Canadian, international, and state wildlife agencies. One result of his work with CONSEP is the table you see in many state fish and game regulation books that provide recommendations for shot type, shot size, and choke. Another is the CONSEP wingshooting clinics held by state agencies across the United States that help hunters learn to pattern non-toxic shot and to shoot it effectively.

Roster also holds several patents, primarily on wads for non-toxic shot, and was a pioneer in buffering lead loads. In short, if you shoot a high-performance duck load, Tom Roster is, in some part, responsible for it. Even after 50 years of research, Roster isn't done yet. When I contacted him for some biographical questions for this piece, he was in the field, testing ammunition on doves. —P.B.

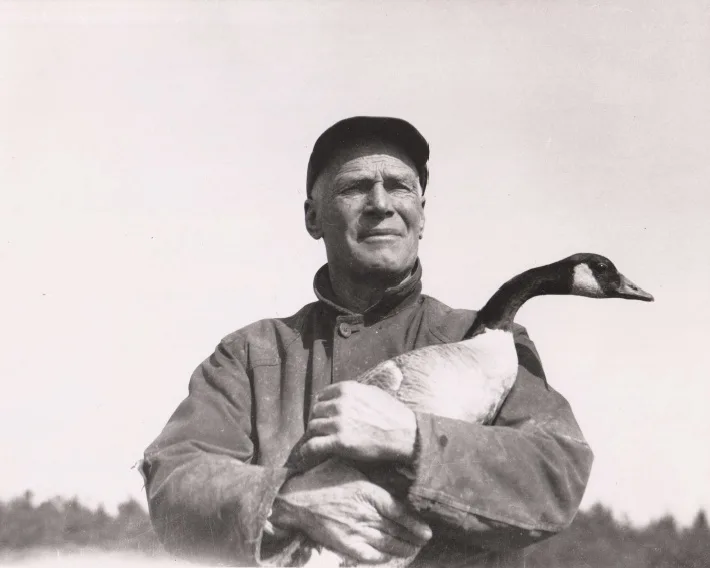

15. Harry Walsh

An Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake physician who grew up poor during the last gasps of the market hunting era, Dr. Harry Walsh spent much of his life collecting the gear of the old waterfowlers and talking to anyone he could about those last, colorful days. Over a lifetime of collecting, Walsh put together an extensive assemblage of the boats, guns, and gear used by the Chesapeake Bay market hunters and stored them at his large historic farm.

In 1971 he published The Outlaw Gunner, which remains one of the foundational works of literature that have framed a modern understanding of the market hunting era. It’s a blast to read, and it was hugely influential, helping spawn a wave of old waterfowling history books that has yet to wane. Its old stories and photographs of punt guns, battery blinds, and sneak boats are a rare window to a time period both glorified and reviled, but one that ultimately led to the conservation of migratory birds across the continent. —T.E.N.

16. Bob Brister

Outdoor editor of the Houston Chronicle from 1954 to 1993, and Field & Stream’s shooting editor from 1972 to 2000, Bob Brister is best known as a shotgunner. He hunted all over the world and shot ducks and geese in Houston’s nearby Katy Prairie. His book, Shotgunning, the Art and Science, remains a classic, in no small part because of the moving pattern tests. Using a station wagon, a boat trailer, 16-foot rolls of paper, a private airstrip, and his wife, Sandy, as the driver, Brister patterned countless shells at the towed targets to learn how shot-stringing could rob a pattern of density on target.

When lead was outlawed, Brister’s tests showed steel had much shorter, more efficient strings than lead. At a time when hunters were resisting the switch to steel, Brister separated fact from fiction and helped hunters learn which chokes, loads, and shot sizes worked best with non-toxic shots. Although Brister received plenty of criticism from hunters for sticking up for steel shot, he had no agenda. He reported objectively on what worked, and we are all better off for it. —P.B.

17. Michael Furtman

In the late 1980s, one of the worst droughts of a half-century crisped a region of North America that relatively few outside its boundaries had ever even heard of: The Prairie Pothole Region. Water nearly vanished in the so-called “duck factory.” Across the country, hunting seasons and limits were slashed. Many wondered if duck hunting would ever be the same again.

This made it an unusual, but impactful time for a duck hunting road trip. In 1989, the writer Michael Furtman embarked on a three-month hunting, camping, and reporting journey from Saskatchewan to Louisiana. His book On the Wings of a North Wind sounded the alarm and was the first to introduce many hunters to the wonder of the prairie potholes and the threats facing them. He was a modern-day Rachel Carson. —T.E.N.

18. Pat Pitt

A notorious Tennessee River poacher through the 1970s and 1980s, Pitt turned a corner as a part of the “Poachers to Preachers” program run by the legendary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lawman Dave Hall. Hall persuaded Pitt, Phil “Duck Commander” Robertson, and other game hogs that their illegal gunning was pushing the heritage of waterfowling to the brink of extinction.

It was an argument that rang true for Pitt, who’d just witnessed the birth of his first son, Patrick. In the delivery room, his wife told him: There’s a son you can duck hunt with. "And I got to thinking: There won’t be any ducks left if I keep it up," he says. "I was stealing from them. Taking the resources. I had to stop." Pitt went on a whirlwind tour, speaking to game agencies and conservation organizations about better ways to enforce duck hunting laws—and convince duck hunters of their value. —T.E.N.

19. Jim Cripe

Hunters have used silhouette decoys for hundreds of years, but Jim Cripe was the first to print photographs of live Canada geese onto durable cutouts. In 1991, this was a revolutionary development that would change field goose hunting forever. Cripe created his Spokane, Washington-based company, Outlaw Decoys, and started selling his new ultra-realistic silhouette decoys.

Cripe’s Canadas were durable, lightweight, visually accurate, and came in a variety of sizes and body postures. Soon hunters all over the country caught on, and Outlaw Decoys blew up in popularity. All these years later, field hunters are using lightweight silhouettes more than ever, with high-res images of mallards, specklebellies, and Canada geese covering up decoy spreads. It changed the way hunters approached decoys and opened up the opportunity to set large spreads without having to tow a trailer of giant full bodies. —M.D.J.

20. Terry Denmon

In 1999, Terry Denmon and his friend Murry Crowe developed a battery-operated motorized decoy with spinning wings. At the time, a motorized decoy was unheard of, unorthodox, and what I assume many thought was silly. Even Denmon was nervous about other hunters seeing his crazy decoy in the field. But once he flipped on the switch and the wings started turning, duck hunting changed forever.

His first spinner was powered by a 24-volt caterpillar cab blower motor mounted in a hollow decoy with aluminum wings. He says the idea came from a rice farmer in California with a 6-volt motor and a turning blade. But Terry and Murry took the decoy idea to a new level, and they called it the "Mojo Mallard." In the early 2000s, Mojo decoys were a one-way ticket to a limit of ducks. They were that good, and it didn't take long for hunters to catch on. Today, a number of brands sell spinning wing duck decoys, but it was the original Mojo that started it all. —R.C.

21. Ron Latschaw

Few people create products that completely change the way we hunt, but Ron Latschaw did. His Final Approach layout blinds let hunters hunt and hide where they could never hide before, all while allowing them to be mobile, too. Though Latschaw wasn’t thinking about changing the way everyone hunts. He was trying to make his own job a little easier.

A guide living in Grant’s Pass, Oregon, in the '80s and '90s, Latschaw specialized in dry field hunts. During the season, his daily grind went like this: scout, find birds, get permission, wait for the birds to leave, dig a pit in the dark, hunt the next morning, and fill the pit back in. Repeat. “We’d pit in every night,” he told me once. “I got tired of digging, and I got tired of sitting in a hole with dirt running down my neck.”

He knew it was important for hunters to keep a low profile if they wanted to hide above ground, and the idea of the layout blind was born. The first was a gargantuan three-person blind with sliding doors. He refined the idea and changed the slider to doors. Latschaw founded Final Approach and began selling his first blind, the Eliminator. All of a sudden, hunters could follow the birds, hide in a field, and leave it without a trace. Field hunting, once the domain of a few, became popular thanks to the layout blind. —P.B.

22. Phil Robertson

Duck hunting had its pop culture moment from 2012 to 2017, thanks to Phil Robertson and the Duck Dynasty family. For a time, DD was the number one rated reality show on TV, and while you can argue about whether it brought a flood of inexperienced hunters to the marsh, it definitely put hunters in the public view and in an affectionate light. The Robertsons are still the family of duck hunters that anyone can name.

Long before Duck Dynasty, the Duck Commander was the biggest name among waterfowl hunters of the VHS era. Phil Robertson grew up hunting in Louisiana, and despite showing NFL potential as a Louisiana Tech quarterback, he followed his heart into duck hunting, then call-making. In the 1980s, he began releasing a series of videos featuring a family of bearded, face-painted Cajuns, who dispatched cripples by biting their heads, and who did their deer hunting by shooting whitetails that wandered into the decoys. Duck Dynasty and the Duckmen live on YouTube, and Duck Commander calls are seen in blinds from coast to coast. —P.B.

23. Wade Bourne

Nobody has ever been more closely associated with Ducks Unlimited TV than Wade Bourne. For over 10 years, Bourne hosted DUTV, traveling the country and sharing stories about waterfowl conservation and duck hunting heritage. Bourne was also a full-time outdoor writer with over 3000 articles published in varous regional and national magazines. He authored multiple books, including Ducks Unlimited Guide to Decoys and Proven Methods for Using Them and Ducks Unlimited Guide to Hunting Dabblers.

Bourne's dedication to wetlands conservation made him one of the greatest ambassadors of the sport. He was the guy who greeted duck and goose hunters on their televisions at home every week for over a decade. And Wade used this platform to share the importance of wetlands conservation. "More habitat on the ground means more ducks and geese in the sky," he'd often say during DUTV episodes.

He was a regular contributor to Ducks Unlimited Magazine, and his thousands of articles about duck hunting tactics, strategies, and travel were read by waterfowlers all across the country. He even encouraged me to pursue outdoor writing as a young kid after I won a local newspaper contest. An example of his kind personality and devotion to the future of waterfowling. —R.C.

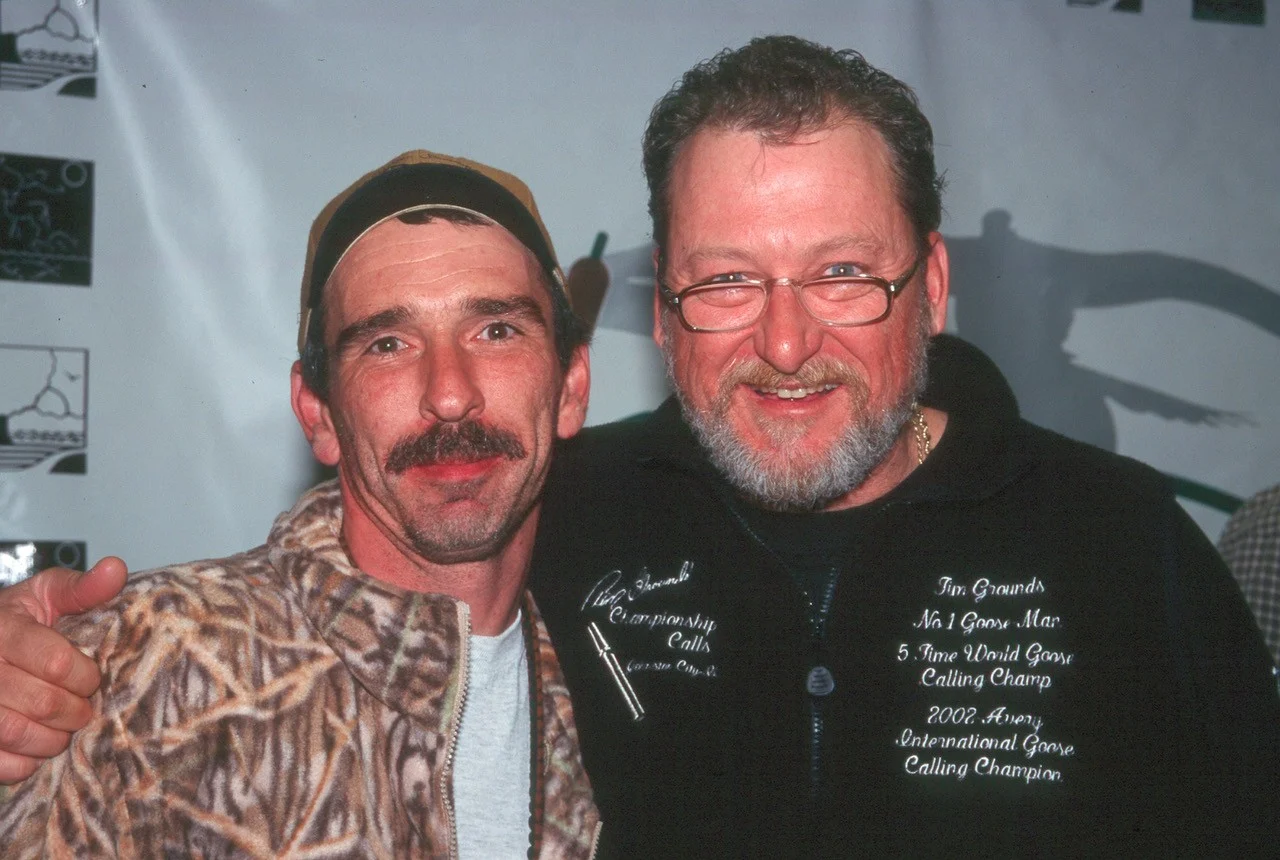

24. Tim Grounds

Tim Grounds was an innovator in the goose-calling world. As the story goes, he first learned to “speak Canada” by modifying an Old School P.S. Olt A-50 flute style call, mainly because he was looking for something different. Something truly goosey. He wanted a call that sounded real, but the operation of which didn’t require an understanding of nuclear physics.

In the late '80s, Grounds designed his now-famous Half Breed, arguably one of, if not the first short reed goose calls ever created. This new call had it all—highs, lows, volume, subtly—bringing versatility to a new level. Soon, the short reed had a following like none of its predecessors. One that continues, thanks in large part to Grounds, to the modern day. —M.D.J.

25. Tony Vandemore

Tony Vandemore popularized duck hunting as a year-round cycle of management and harvest in the same way deer hunters manage properties. He operates Habitat Flats, one of the nation’s very best commercial operations and he runs successful spring snow goose hunts as well. Vandermore and some friends started Habitat Flats in the 2000s and made duck property management the dream of every duck hunter. Still, he thinks of himself as a duck farmer, planting corn and managing moist-soil units, building blinds and dikes, putting in enough work in the off-season that carrying clients every day of hunting season feels like a vacation to him.

From teal to big ducks to honkers to spring snows, Vandemore hunts more than anyone I’m aware of, and he still loves it. The last time I hunted with him, we stood by trees on a gray, blustery day, and by late morning, we had shot several ducks. He asked if we wanted to go in. I thought the sun might peek out and bring us some mallards, and I said so. Most guides wouldn’t even ask. They’d just hustle you out of the field so they could get on with their days. Tony Vandemore isn’t most guides, and like no guide ever, he said: “That’s fine. I’ve got no place else I’d rather be.” —P.B.