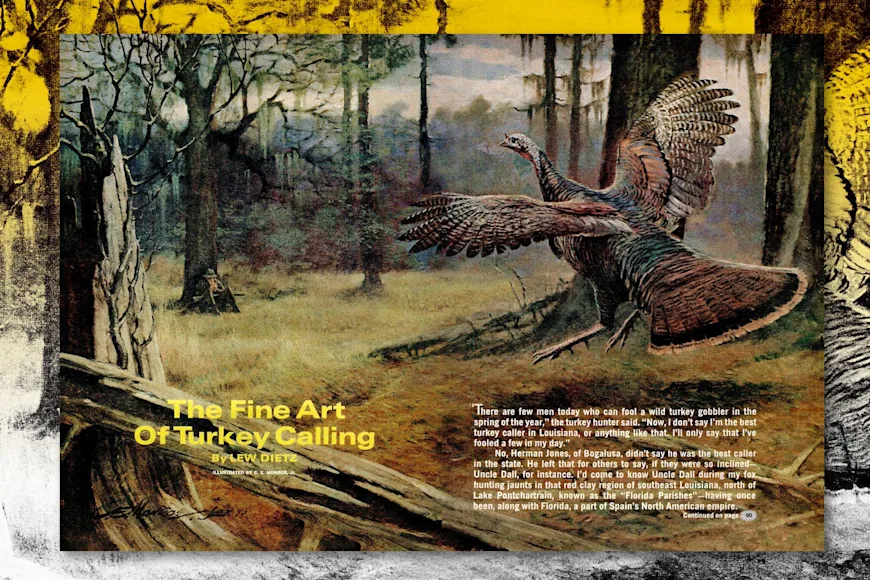

“THERE ARE few men today who can fool a wild turkey gobbler in the spring of the year,” the turkey hunter said. “Now, I don’t say I’m the best turkey caller in Louisiana, or anything like that. I’ll only say that I’ve fooled a few in my day.”

No, Herman Jones, of Bogalusa, didn’t say he was the best caller in the state. He left that for others to say, if they were so inclined—Uncle Dall, for instance. I’d come to know Uncle Dall during my fox hunting jaunts in that red clay region of southeast Louisiana, north of Lake Pontchartrain, known as the “Florida Parishes”—having once been, along with Florida, a part of Spain’s North American empire.

Uncle Dall, a fine old gentleman who knows his turkeys almost as well as he knows his foxhounds, suggested that I seek out Herman if I was interested in the fine and ancient art of talking turkey.

I’d hunted the wild turkey in other sections of the South and had had just enough exposure to the sport to be convinced I’d need another lifetime in the swamps and river bottoms before I could call myself an expert turkey hunter.

The only truly good turkey hunters I’ve met have spent a lifetime at it. And in this matter of talking turkey and having the turkey talk back, I’ve run across a scant half-dozen who qualify as masters of the art. There are the myths, of course, callers the likes of Jeb Lester who they say could call a gobbler out of his grave and, indeed, is reputed to have lured the boss gobbler out of Honey Island Swamp and all the way across St. Tammany Parish. Today’s Louisiana turkey hunters appreciate the myths, but most agree that though turkey calling may not yet be a lost art, it most certainly is a vanishing one.

Herman Jones, when I met up with him, put it this way: “A man just don’t go out one spring day and decide to fool himself a gobbler. If you want to call a turkey, you start like I did at 16 and learn from your daddy and uncles. Then you go out in the swamp and learn from the turkeys themselves. Then you spend the rest of your born days trying to fool a bird that has all the advantage because he’s a turkey and you’re nothing but a man.”

Louisiana is one of a number of Southern States offering a spring gobbling season. Most Southern States have a general open season on turkey in the fall, but it is the spring of the year—when the gobbler is brimming with passion and can be teased, lured, or conned by an artful simulation of the cluck or yelp of a yearning hen—that the true turkey hunter points for.

The “toe of the boot” section of Louisiana has been prime turkey hunting country as far back as the mind goes. The flood plains of the rivers which drain this wild territory once supported the finest stands of longleaf pine in the world. Much of this great forest has been lumbered off to be replaced by slash and loblolly pine. The river bottoms and swamps are bordered by oak, beech, hickery, and gum, supplying the mast so essential to the wild turkey.

If you want to call a turkey, you start like I did at 16 and learn from your daddy and uncles. Then you go out in the swamp and learn from the turkeys themselves. Then you spend the rest of your born days trying to fool a bird that has all the advantage because he’s a turkey and you’re nothing but a man.

The turkey went under statewide protection in 1931, and it was only in 1955 that Louisiana turkey hunters were once again offered a chance to match wits with this finest of American game birds. Since that time, good management, stocking programs, and strict law enforcement have conspired to restore this indiginous bird to his native haunts.

This hiatus explains, in part, why a really good man nowadays is hard to find, if it’s fooling gobblers you have in mind. Herman Jones is doing what he can about that. Since a serious operation six years ago, Herman doesn’t hunt, himself; it’s his pleasure, though, to call gobblers for others to introduce a new generation to the ancient art.

“One thing I’ve learned,” Herman will tell you, “you can’t give a gobbler an even break. If you do, he’ll fool you every time. You have to take advantage of that bird. It’s his gobble that gives him away. So if he don’t gobble, you got to make him gobble.”

This departure from the usual procedure of slipping into the swamp at the first crack of light and waiting for a roosted tom to give his position away when he proclaims the dawn, is a gambit Herman learned from his father. “My daddy told me to start the owls and the owls will start the gobbler. I hoot a few times, two or three minutes apart. I bring an owl to me. Then I let him take over and pretty soon other owls will cut in on him and soon they’ll have a fuss going. For some strange reason, owl fuss is something a gobbler can’t take for long. If that gobbler is going to open up at all, he’ll open up right then.”

The cover from the November 1970 issue of F&S targeted waterfowlers. Field & Stream

Once Herman has located that roosted bird he moves in to what he calls striking distance, for him around 150 yards. “No, I don’t make myself a blind. My daddy told me never to try and hide from a gobbler. I find a tree in an opening—you can’t call a wise old bird into a thicket. That tree’s got to be big enough to shadow my body. I face in the direction where I heard that gobbler. If I’ve got on protective coloring and I don’t blink an eye or move a muscle, that turkey’s not going to see me.”

Next comes the critical stage of the operation, the make-or-break moment. “First, I make that flat cluck that the hen turkey makes only in the mating season. That cluck—the flatter the better—has got to be right. And it should be pitched right at the gobbler, not past him. If he don’t answer right off or fly to me, I wait till the second time he gobbles and cut right in on him with a Kre-e-e-e PUCK-taw. The timing is important. Most callers don’t realize how important the timing is. You might call timing one of the secrets of my success.”

The Ideal Turkey Hunt

Herman chuckled as he recalled how one morning he stole a gobbler right out from his competition. He went into the swamp with a pair of hunters who had heard of his skill and had asked if he would bring a tom to their guns.

When he got into the swamp there were so many hunters out there it sounded like a deer hunt. “There was one fella yelping from the east and another from the west. They didn’t know what they were doing. Sounded like they were using little old boxes. This one fella says to me, ‘Now, Herman, let me shoot this one.’ I laughed. ‘Fine with me,’ I said, ‘but I don’t see how we’re going to have any luck at all with all that crazy yelping going on.’ But anyway, I got into striking distance and made that sound of the hen strictly for mating. That gobbler came right back at me. I knew he wasn’t paying any attention at all to those other fellas. He gobbled again, and when he did I cut right in on him. Caught my timing just right. When the gobbler came back with a double gobble, I knew I’d got to him all he wanted to hear. The gobbler didn’t drop down and walk to me that morning, he flew to me. That fella got his turkey, but you know, he never did understand that there was anything special about calling a turkey through that kind of fuss.”

Ideally, turkey hunting should be a solitary sport with two perhaps company and three certainly a crowd. Also, ideally, a turkey hunter should have a sizable piece of swampland to himself when he sits down to work his gobbler. Although it is not, and never will be, a sport to attract the masses, the ranks of those who want to get in on the gobbler action swell each year, a fact which frequently leads to a competitive situation.

Common Calling Errors

A caller never goes out seeking competition, but it is on those occasions when he meets it that his skill and wile are truly tested. This day, Herman was on the Louisiana side of the Pearl River, which forms a part of the state’s eastern border, when he heard that gobbler sound across the water.

“Now I’ve heard men say they can call a gobbler across water,” Herman said. “I’ll only say that I can’t do it and personally I’ve never known anyone who can. Anyway, I decided to paddle across the water. I didn’t have a license for Mississippi and I felt a bit nervous as I worked around a pond trying to get in striking distance of where I’d heard that gobbler.

“Then I heard this fella owling. Let me tell you, he knew what he was doing. He’d single owl then whip right back with a double owl. When he done that, the gobbler cut right in on him. From where I was you could have taken a tape measure and I swear that turkey was exactly halfway between him and me. But I had the advantage over this other fella. He didn’t know I was there. And I was ready. When that gobbler cut in on his owl, I cut in on that gobbler with my Kre-e-e-e, PUCK-taw. And when I put that noise on him, the turkey come back with a double gobble and I says to myself, ‘Whoever you are out there, you better hurry because he’s headed my way.’

“It wasn’t five seconds later that I heard that gobbler’s wings pop one time before he hit the ground. And there he was, a beautiful sight; his head like a patent leather shoe, those beautiful Indian beads on his bronze feathers gleaming in the sun! I walked right out in the open after I’d shot that gobbler, hoping I would meet that fella. He was really good. But he never did come to meet me. Only thing I could ever figure was that maybe, like me, he’d paddled across the water and didn’t have a license in Mississippi.”

I saw almost as many varieties of calling devices as I saw turkey hunters in Louisiana that week. Many old-timers still swear by the hollow second joint of a turkey wing and a few use short, telescoped lengths of cane. There were numerous cedar sounding boxes you strike with slate and cedar-against-cedar combinations. Growing in popularity are mouthpieces consisting of a rubber membrane fixed in a metal horseshoe. Callers have told me that this last contraption produces a passable cluck but a less than acceptable yelp. Herman Jones spurns the use of any mechanical gadget, relying only on a tender leaf or a blade of grass. However, he can execute his repertoire by striking a piece of hard synthetic rubber against a piece of slate.

With a bit of practice a pro can learn to produce a reasonable facsimile of the turkey cluck on any one of these devices. The yelp, or the series of quick little cries, is something else again.

“A beginner can too easily make a scare-‘put,’ the sound the gobbler makes when he’s alarmed,” Herman warns. “Once you do that, your bird is long gone.”

Another common error is to call too much. Forbearance and patience, those ancient virtues, pay off double in turkey hunting. Turkey hunters will tell you that a gobbler’s eyes are 1,000 times as sharp as a man’s, insisting that he can easily pick up the blink of a human eye at thirty paces. Possibly admiration which approaches awe leads the turkey hunter to hyperbole, but the incredible keenness of his ears must be vouchsafed by the proven fact that he can pick up the muted cluck of a hen a quarter-mile off. He’s also a ventriloquist. Only an expert can unerringly course a gobbler as he comes in to call. To all this, add his talent for performing the vanishing act and you have quite a game bird.

How to Fool a Boss Gobbler

It is unlikely that wary old boss gobblers would ever be taken were it not for expert calling in the spring gobbler season. Management men and knowledgeable turkey hunters agree that the elimination of these lordly despots is something to be desired if the youth of the species is to be served.

The gobbler is a male chauvinist. Humphrey Bogart’s famous movie line to Loren Bacall, “When I want you, I’ll whistle,” expresses the boss gobbler’s masculine attitude.

Herman fooled a venerable old gobbler in the swamp one morning. He was admiring the trophy bird when along came an old man. He stooped over and felt the gobbler’s spurs and said in a tone of awe, “That’s him! Yes sir, that’s him! Why that old rascal’s been driving all the young toms out of this piece of swamp for three years. I’m sure glad you got that old gentleman.”

Herman insists that it’s the spurs rather than the beard that best indicate the age of a tom turkey. The beard is frequently worn off with the years, but a gobbler’s spurs never lie. This, too, Herman learned from his daddy.

“When he was a very old man and his sight was failing bad, I’d go out to see him after a morning in the swamp. ‘You go this mornin?’ he’d ask me. “Yes sir,” I’d say, ‘I went.’ “You hear one?’ he’d ask. ‘Yes sir, I heard one.’ ‘Didn’t let him get away, did you?’ Then I’d let him feel of the beard; he was almost blind. ‘No sir, he didn’t get away. Here’s some of him.’ But he wouldn’t pay any attention to that beard. He’d take his finger and run it along the spur. “Well, now,’ he’d say, ‘that gentleman is either 5 or 6 years old. Don’t you ever forget what you put on him today because that’s all you’ll ever need to call the wisest gentleman gobbler that ever lived.’ So I would make the sound I’d put on the gobbler and he would shake his head. ‘Boy,’ he would say, ‘I thought my own daddy was the best there was!” “

Herman went on to explain how it was that his father arrived at the age of a gobbler by the spur. “You see, the young gobbler starts out with nothing but a bump for a spur. The spur grows year by year and when he’s 5 or 6 that spur begins to curl, and the older he gets the more it curls and the sharper it gets. So you can see why young gobblers think twice before they try and poach on a boss gobbler’s harem.”

Most turkey callers agree that gobblers come easier to their call in the early season, before the hens have begun to feel the full tide of the sex urge, and then again late in the season when most of the gobbler’s concubines are setting on eggs and feel their part in perpetuating the species is over for the year.

The gobbler is a male chauvinist. Humphrey Bogart’s famous movie line to Loren Bacall, “When I want you, I’ll whistle,” expresses the boss gobbler’s masculine attitude. In the spring of the year he’s convinced he’s the most beautiful and desirable creature on earth, and when he gobbles he’s saying, “Girls, here I am. He expects the hens to come to him, and so it is during those periods when they don’t respond readily that the gobbler is most vulnerable. It is then that the smartest old bird can be a sucker for a seductive cluck or a yearning yelp.

Of course, part of the lure and fascination of spring turkey hunting is that a man never knows what to expect. No two gobblers respond in the same way and seldom are the circumstances the same. As a rule, a gobbler sounds off before he flies down from his roost and then hushes. But occasionally a gobbler will drop down without a sound and then fuss and gobble for hours.

Most hunters agree that when you alarm a gobbler and he goes off with a “put,” he’s gone. But one day Herman alarmed a gobbler and heard him go off out of hearing, only to suddenly hear him coming back and right to his gun. It was only after he’d shot the bird that he realized that it was not the same bird he’d frightened but a young tom that had met the boss gobbler as he headed off and decided to make tracks in the other direction.

Turkey hunters, when they gather over bourbon and branch water or a catfish and hush puppy feed, tend to agree that there is no game in the woods that offers more challenge than the eastern wild turkey. It is on the fine points of meeting the challenge where differences of opinion develop. Some hunters consider it a waste of time to set forth on a cool, windy morning. Others—Herman Jones included—insist that a chilly morning won’t inhibit a gobbler once the mating season has begun, so long as the wind is still and the sky is clear.

And there is much argument over the distance at which the gobbler should be taken. Herman’s distance is twenty to twenty-five paces. “What I used were 72’s or 8’s in a full-choke barrel and that was the right distance for my gun. It takes only one pellet in the head to kill the biggest turkey, and a man should always shoot for the head. Hit him in the body and you’re likely to lose him. And even if you don’t, the meat is spoiled.”

Nor will Herman Jones work a turkey once he’s come down from the roost. “I call it a waste of time. When a turkey comes off the roost he has his mind made up on where he’s going and all the fancy calling in the world won’t change his mind. For me, turkey hunting is short and sweet. I go in at dark and work my turkey at first light. I either lose or have my turkey within half an hour.”

Perhaps the finest tribute paid to Herman for his calling was offered by a bobcat who mistook him for a turkey. This unnerving experience occurred right after his operation six years ago. He wasn’t supposed to be driving a car but, as he puts it, “I just had to get out in the swamp where I could see that pretty timber.”

He was just relaxing and working on his calling repertoire when a movement caught in the edge of his vision. “I didn’t move my head, fearing to scare whatever it was. The last thing I expected to see when it came into my sight was a John Brown bobcat. It kept on a-comin’, and when it got within 10 feet of me, I says to myself, ‘I got to get that thing off me.’

Herman fetched home a bobcat instead of a turkey that morning. This experience, unsettling as it was, is unlikely to keep Herman home when the sweet gums are leafing in the river bottoms and the turkey gobbler, feeling his primordial urge, proclaims the break of day.

As one turkey hunter I met on the Amite River expressed it, “I don’t care what you’ve done and where you’ve been, you’ll never find anything to compare to that experience of seeing a gobbler coming in to your call. You see him come at a full strut, swaying to a rock-and-roll beat, and you sweat, man, you sweat!”

Herman Jones, after fifty years of talking turkey in the river bottoms of Louisiana, is no less vulnerable to the allure of matching wits with this magnificent game bird. “I keep going,” he says, “and mostly I guess it’s the knowing that when you fool yourself a wild turkey gobbler, you’re fooling the wildest and smartest thing in the woods.”

_Read more F&S+

stories._