by T. Edward Nickens

Walter DeSales Witt was in a good place: with his back against a hemlock, green boughs dropped with snow all around, like a half-opened umbrella.

He’d wormed his way under the branches, spread out a burlap sack for a makeshift seat, and now he could watch a deep-woods edge where hardwoods transitioned to a stand of hemlocks. It was dark Pennsylvania timber, just the kind of route a big buck might travel.

It was good to be out of the house. No one would ever forget the big storm of December 1974. The snow started falling the night before the antlered deer season opener. It was a Sunday night, and the Witt family was at Grace Brethren Church, in the small town of Meyersdale, Pa., in their customary pew on the right-hand side, a third of the way back from the pulpit. Eight inches of snow fell during the church service alone. The overnight total pushed three feet. It would be nearly two weeks before anyone went anywhere in Somerset County. And in two weeks, buck season would be over.

The Witts, a family of hunters, weren’t going to let the season slip away without a try. When the roads were finally cleared enough for travel, Walt, 38, packed his red-and-white Plymouth station wagon with his two boys, Dan, 14, and Mark, 12, and his father-in-law, Roy “Pap” Brown. Now the Witt men were hunting together, on family land, on the very last day of buck season. It was an exciting day. Witt’s wife, Cathaleen, had graduated from college just the day before. She was now Christmas shopping with their daughters, Lisa, 9, and Victoria, 17. It had been a tough stretch, raising four kids on $3,500 a year.

For Walt, a ninth-grade earth science teacher and high school track coach, one of the great joys of a few hours in a quiet stretch of woods was the blessing of unfettered thinking. His true calling was sharing his Christian beliefs. In a given year, he might guest-preach at dozens of small Allegheny Plateau congregations. He talked to nearly everyone he met about his faith: the kids on his track team, a lady in the grocery store, a man picking blueberries on a mountain roadside. Tomorrow morning, Walt would speak from the pulpit of Calvary Bible Church in nearby Ellerslie, Md. He’d already started writing the sermon, titled simply, “Heaven.” The passage he’d chosen spoke of heaven’s streets of gold. Of all the blessings of his life, Walter Witt held nothing more dear than the certainty of where he would spend eternity.

Now he peeled an orange, let the rinds fall to the snow, bright orange slashes like leaves curled against the cold, on a carpet of white flecked with the dark needles of hemlock. The day was warming, and as melting snow dropped from the tree boughs the branches would suddenly spring up, dipping and dancing. Each movement would catch Walt’s eye, surely bringing a rush of adrenaline. It was just the kind of thing no deer hunter would miss.

One hundred forty-eight feet away from Walt, another hunter watched from the cover of another snowy hemlock. Something was moving in the trees up ahead. There was a patch of fur. It had to be a buck. For 15 minutes, the hunter watched. Then, in the early-afternoon hours of Dec. 14, 1974, the crack of his rifle split the quiet, dreadful woods.

Homecoming

_Walt, “Pap” Brown, and Walt’s sons, Dan and Mark, trudged in near silence by the light of the moon on new snow, in single file, breaking through snow clear up to the boys’ waists. They huffed under apple and walnut trees, past Brown’s spooky cattle barn that the brothers feared even in daylight. Walt dropped his father-in-law off first, to take a stand in the woods, then his oldest son, Dan, and Mark last. Dan hunted near a large sawdust pile where his ancestors had buried their ice blocks. Slightly elevated, with a broad forest view, it was a good spot, and he was wide-eyed with the thought of a deer coming through the woods. Mark was just as excited. This was his first deer hunt. He watched his dad walk away, passing behind trees, growing fainter and fainter in the gloaming light in and out of sight. Now he could see his dad, now he could not.

Walt didn’t hike much farther. A few hundred yards, maybe, and then he could make out the hemlocks just downhill. This was the spot. He didn’t want to be too far away from his youngest son. These were familiar woods to the boys, but with this much snow, well, nothing looked quite right._

On a hot June Sunday afternoon, Dan Witt and I pull off Pennsylvania’s Highway 160, 5 miles east of Meyersdale and a few hundred yards from the site of “Pap” Brown’s old farmhouse. Rolling ridgelines unfurl to the horizon, checkerboarded with forest, farmfield, and pasture. In a dirt parking lot, Mark Witt and Ron Askey, the Pennsylvania game warden who investigated the shooting of Walter Witt, lean against Askey’s truck. They greet us like old friends meeting at the edge of a dove field. Askey is built like a fireplug, with a heavy jaw and gray locks over a ruddy forehead. Mark is wiry and bald with a mustache. He shares Dan’s dark eyes but not his laid-back demeanor. Dan describes him as a jokester and prankster and a bundle of energy, but if he has the jitters today, I can’t blame him.

In the last 37 years—and in particular over the last half decade—the Witt brothers have experienced a remarkable journey of healing and redemption. Since 2004, Dan and Mark have spoken about their father’s death and their personal stories of spiritual renewal at churches and church-sponsored sportsmen’s dinners from the mountain hollows of West Virginia to the plains of Alberta. They’ve written about how losing their father in a hunting accident impacted their growing up, their approaches to hunting, their marriages and family ties, and most emphatically, their relationship to God. Without ever seeking the opportunity, the brothers have found themselves on a path whose turns and ultimate destination they each view as an unfolding miracle.

But there is one thing they have never done: return to the woods where their father died.

A few miles away from Walt’s line of hemlocks, along the lower flanks of Wills Creek Mountain, four hunters gathered with their own buck dreams. Two of them had a special reason to celebrate a Pennsylvania hometown sunrise. Twenty-four-year-old Johnston Cutler1 was just three months out of a two-year stint with the U.S. Army. He’d grown up hunting and fishing in the Allegheny woods with his dad, but between his college years and military service, the pair hadn’t hunted together in six long years. Now the woods were waking up around the father and son. The plan was to drive deer to a couple of standers, and the young Cutler was happy to be on the shooting end of the arrangement. He slipped into the woods, looking for deer.

For Dan and me, it had been a five-hour drive from his Virginia home to his native Pennsylvania, and despite our chatter about the upcoming deer season and Dan’s training regimen for a backcountry elk hunt, the interludes in our conversation had grown longer and more solemn. We wondered if we could find the woods where Walt took in his last view of bare winter trees, where he sat with his back to a hemlock, watching for a buck, listening for a shot that would tell him that one of his boys had downed a deer.

After nearly four decades, nothing would look the same. Askey was 31 years old at the time of the accident; now 68, he has bad knees but plenty of grit. He was astonished when I first contacted him about this story but never hesitated about returning to the scene. By triangulating the memories and recall of the three men, we thought we could get close to the piece of ground where Walt sat. We wondered if we might even find the tree.

After handshakes and small talk, we douse ourselves with bug dope and drop off a long, flat ridgetop into the overgrown fields and woods below. Askey is chatty and avuncular. Mark spins good-natured jokes about his boyhood memories, a broad smile appearing under his aviator sunglasses, but Dan grows somber as the trail falls off the ridge into a mosaic of tangled fields and woods. The brothers point out a few apple trees that still remain from the family orchard. We skirt the site of the old barn. Soon the path enters a grove of birch and maple and locust. In 1974, this would have been open fields. “Corn, mostly,” Dan says. “It was great for rabbits.” There are bear droppings and deer beds. There are long, quiet moments.

I first met Dan a month earlier, at his home on 21 acres of rolling Blue Ridge woods outside Lynchburg. Married for 25 years, and with two grown boys, he’s the assistant town manager of nearby Altavista, a town that reminds him of Meyersdale. “It has that small-town feeling,” he says. “The folks are extremely resilient.” It’s also a location with plenty of access to deer woods, and despite the nature of his father’s death, Dan remains a serious hunter. A few days after the funeral, in fact, Dan was up before dawn, dressed in his hunting clothes, heading out for one of the last of Pennsylvania’s doe days. His mother stood in the doorway, shaking with fear.

“I lost my husband,” she’d said. “I’m not losing a son.”

But Dan never lost his desire to hunt. “Mom hated hunting and didn’t want us in the woods,” he tells me. We’re sitting on a sofa in the small living room he’s just built for his mother-in-law. “But I’m an introvert. I didn’t have a lot of friends. Out in the woods is where I felt I could be me.” After Walt’s death, Don Imhoff, a family friend who had once run track under Walt’s coaching, took Dan under his wing. The pair hunted and fished, ran a trapline together, and took up bowhunting with a shared passion. When Dan started college at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Imhoff moved down with him to take a few college courses. It was a healing friendship.

For the Witt family, there will always be unanswered questions about that day in the deer woods, inevitable appraisals of how and why and what could have led, ultimately, to the firing of the bullet that struck Walt dead. But in the weeks and months that followed the accident, more pressing was the doleful reality of simply rising from bed and making it through the day until it was time again for fitful sleep. This is the story of grief: endless days of dark until slivers of light begin to grow into minutes and then hours, and life becomes life again, never the same, but life with laughter and love where once they could not have been imagined.

As Dan describes those times, those months and years, he sits with his right leg crossed over his left, his foot ticking nervously. The rest of the house is silent; Dan’s wife and mother-in-law and sons have retreated to distant rooms to cede us space and quiet. He wears cuffed khakis and a yellow-striped oxford shirt and a black-and-gray goatee. He has dark eyes—dark brows, dark irises—and they are not unfriendly, but they are unflinching. His was a small-town tragedy, and he got through it by getting on. His mother taught school. People pitched in.

But throughout his teenage years, Dan lived with a rising tide of anger. He expressed his anguish on Somerset County’s winding roads, pushing his 1973 Plymouth Satellite to 110 mph, then 115 mph, speeding “until something started floating around inside the car or the doors were rattling. I can’t tell you how many times I did that. I was daring God to kill me.” Dan remembers sitting in church as the choir sang:

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound,That saved a wretch like me.

“And all I could think was ‘You are the wretch, God, for allowing this to happen to my dad,’” Dan says. “I internalized all the anger. It just built up in me.”

For Dan, spiritual healing was first revealed in a conversation he had when he was in his early 20s, with a former neighbor named Peter Cabin.2 At the time of Witt’s death, Cabin owned one of the hard-drinking bars in Meyersdale, and when Dan questioned God about his father’s death, the question was always the same: Why Dad and not a man like Peter Cabin?

Then one day, while visiting his grandmother, he heard someone calling his name from a nearby house trailer. It was Cabin, and he wanted to talk.

“I knew who he was,” Dan says. “And I was thinking, ‘You’re the one that should be long gone. I should be talking to my dad.’” But Cabin told him an astonishing story. Walt, as it turned out, never passed up an opportunity to share his faith with Cabin, and after the hunting accident, the barkeeper converted fully to Christianity.

“And that’s not all,” Dan says, shaking his head, amazed at the turn of events even after 25 years. “He sold his tavern. He started preaching. He began a ministry in retirement homes because he felt that those people didn’t have much time left before eternity. And for years he helped smuggle Bibles into China. All because of my dad’s death.

“When he told me that story,” Dan continues, “it was like God hit me right between the eyes with a two-by-four. This light came on of God telling me, ‘Dan, if you were in charge of this, if you were God, Peter Cabin would be dead today, and he would have to spend an eternity with no hope. I didn’t make a mistake with your dad.’ It was an epiphany, and the beginning of the healing process for me a decade after Dad’s death.”

It was a needed breakthrough, because Dan carried a particular burden about that day in the deer woods. What he remembers most clearly about that snowy Pennsylvania hunt, what he can recall in the most exquisite detail, are those few minutes when he left his stand and tried to follow his father’s tracks in the snow, to tell him that he was tired and cold and ready to go home.

“I could see where Dad’s tracks turned off into the woods,” he says. His foot twitches. “I followed the trail until it got really steep.” As he speaks, Dan cups each hand, palms facing downward, and pantomimes the struggling gait of a young boy—each step a short, shallow arc in the air, reaching, stretching, searching for his father’s tracks in the deep snow. “It was really hard. I got really tired.” His foot stills. There is no sound other than his voice. “I yelled and yelled, but with the snow…”

Dan can’t count the number of times he has asked himself: What if I had never stopped? What if I hadn’t given up? The answers hang in the air, unspoken and obvious. They would have met and chatted. Walter Witt would have scooted over to make room for his oldest son on his burlap sack. For sure, they would have made a meaningful, warning fuss.

Dan wipes the palms of his hands down the front of his khakis. He uncrosses his legs, and nods his head. He falls quiet, and for the first time his dark eyes glisten.

Walt was a patient hunter. He knew this farm well. He knew that deer liked to slip along the edge of the dark timber on their way to bed after feeding near the apple trees his wife’s grandparents had planted years ago. It was cold, but there was no rush. He ate a sandwich and a candy bar, sipping water from a ketchup bottle he’d washed and used as a makeshift canteen. There was little money to spare in the Witt household, and you had to make do. But now, with Cathaleen’s newly minted education, well…life just might get a bit easier.

A Brothers’ Mission

The field edge where Walt led his father-in-law and sons is now a faint trail in a scrub of second-growth forest, and we wade through blackberry, ferns, and poison oak. Nothing looks like it did, but neither Dan, Mark, nor Askey is surprised by this. “Some of these pines were knee-high back then,” Mark says. “But a lot of these woods were just open fields.” As we descend toward Wills Creek, Askey’s yellow Labrador retriever, Winchester, runs ahead, tail wagging above thistles and briers. He’s the only one of us not on edge.

Within a few minutes, Dan disappears into the woods, calling out deer sign. I follow Mark, who peppers Askey with specifics.

Where did the other hunting party park?Was somebody else on stand with Cutler?What witnesses were interviewed?What did they see?

It’s been this way for a long time. While Dan seems resigned to the ultimate mysteries of his father’s death, Mark has always pushed for more details, more specifics, more answers. A civilian logistics engineer with the Department of Defense in Alabama, Mark is in charge of support details for helicopter crews in Afghanistan and Iraq, and he takes a critical, analytical approach to confronting the unknown. When the brothers speak at events, Dan opens up with hunting stories and a personal testimony of what his father’s death has helped him understand about God. Mark is more evangelistic. He’s a kidder with a big smile, but he closes the talk with a sermon’s defining motif. Mark isn’t satisfied until his listeners grasp his core belief: God presents each person with a decision to make—what will you do about Jesus Christ?

And for Mark, too, anger at God defined his adolescence. For years, Mark wouldn’t even talk about the day and would leave the room in a fury whenever his father’s death was mentioned. “I was raised in the church,” he says. Sweat runs into his eyes as he swats spiderwebs from his T-shirt. “But when this happened, it was like God made a mistake. Because of who my father was, how grateful he was to be a Christian. You don’t let good people die.”

Healing for Mark came years later, when, in his early 20s, he began teaching a Sunday school class for youth. Reaching out to kids who had their own hurts and questions was a turning point, and even now it appeals to Mark’s penchant for directness and absolutes. He doesn’t mince words to his students. “I tell my kids to go home and tell your parents you love them, because you might never get another chance. In a cemetery, you see tons of headstones that say stuff to other headstones: I’m sorry I didn’t tell you this… I’m sorry I didn’t say I love you… But it’s too late. You don’t know if you have another moment.”

Mark stops short, and looks up the hill. We can see blue sky winking through the trees, marking the edge of an old field. On that hunt long ago, Mark didn’t last long in those snowy woods. Cold and tired, he headed back to his grandparents’ farmhouse sometime before noon. He was there when he heard sirens, and learned of the accident.

In 2004, a few weeks before the 30th anniversary of their father’s death, the minister at Meyersdale Grace Brethren Church asked Dan and Mark to come home and share their story to a congregation that had never forgotten Walter DeSales Witt. Neither brother had ever considered such a public forum. “We looked at it as an opportunity to just let people know we were O.K.,” Dan says. “We figured hardly anybody was going to be there, but it was standing room only.” He is still struck with wonder at the response. “The setting of being back home was…” His voice trails off to silence. “That night was really emotional.”

Word of their presentation spread, and invitations to speak at other churches began trickling in. The Witt brothers visited a small church in West Virginia, then another church back in Meyersdale, and traveled to wild-game dinners hosted by area churches as an outreach effort to men. “You tell a deer hunting story, and it doesn’t matter who the person is,” Dan says, laughing. “It’s a deer thing and hunters who have nothing to do with church will come out of the woodwork to listen.” From their first story of homecoming and reconciliation, the brothers’ presentation evolved into a testimony of faith and healing and even redemption. “We have a blast telling great hunting stories,” Dan says, “but we always share our faith and the importance of knowing where you are going to spend eternity for this very reason: We know firsthand that you never know how much time you have left on this earth.”

By now the brothers have spoken at perhaps a dozen churches. In the Edmonton, Alberta, area in July, more than 1,200 people came to hear them over a three-day speaking tour. They published a small tract, titled Mistaken Identity, in which they tell of their relationships with both their father and Jesus Christ, and of how, as Dan says, hunting has helped them understand that sharing their faith “is a part of God’s plan for us right now, whether we understand how and why or not.” Their six-panel pamphlet is unabashedly personal and unapologetically spiritual. Word of it has spread with no advertising or marketing, yet the Witts have gone through nearly 3,000 copies. “People call us up to send more tracts, and I’m like, ‘How did you get this?’” Mark says. “I was cleaning up tornado damage in Alabama and some guy walks up to me with one in hand and says, ‘This is amazing, I need more of these to hand out.’ And I don’t even know who these people are.”

When Walt moved, his Air Force parka rustled against the rough bark of the hemlock. It was a warm coat, with a hood trimmed with wolf fur. His friends rode him hard about that coat. They told him to think twice about wearing it in the deer woods, with that ruff of gray-brown fur. But he needed it on a frigid day like this. After a few quiet hours, Witt heard men in the woods, on the move, hollering to drive deer. Most of the old family farm had been sold off a few years back, and locals had taken to pushing deer through the big woods. Still, it was hard to imagine anyone else would be here, not with the snow and rough roads.

We search the woods for another hour, pushing lower and lower toward Wills Creek. At some point we lose sight of one another; I’m tangled in the briers that thatch the old road, while Mark and Askey cut a parallel course to both sides. Dan has pushed on ahead when we hear him call out from the woods, his voice clear and determined.

“Mark,” he shouts. “Hey, Mark!”“Yeah?”“Come here!”

Consequences

_Cutler had been on stand for about an hour, listening to the drivers holler through the woods, when movement in the dark timber across the slope caught his eye. He stepped up on a limb for a better view. Something was moving at the base of a hemlock tree, maybe 50 yards away. Something was there. For 15 minutes, eyes straining, Cutler picked apart the tangle of drooping branches and dark shadows. Each time a driver would yell, whatever it was under the hemlock would move slightly, as if turning toward the sound. It’s one of the oldest tricks in the book. Most hunters know that a smart buck will do that—lie tight in thick cover and let the danger pass.

If only he could get a better view. About 20 feet from the hemlock, directly in his line of sight, a tree stump jutted from the ground, blocking anything but the faintest motion a few feet above the snow. He didn’t have a scope on his rifle, but he could make out a swatch of gray-brown fur, and a black stripe like the ones that lie along each side of a mature buck’s nose. Every now and then, it seemed as if a deer’s antlers dipped and danced under the hemlock. Otherwise, the animal seemed calm. He might have to shoot just to get it to move. Maybe he could thread a bullet through the branches. If nothing else, that might scare the deer toward his hunting party._

There are two verities that every hunter accepts: Once a shot is fired, it cannot be controlled. The projectile will go where the muzzle was pointed until it hits something dense enough to absorb its energy or hard enough to deflect it along another, equally ungovernable, trajectory. You cannot put a bullet back into the barrel.

And there is never an excuse for one hunter to mistake another hunter for an animal. There may be circumstances that confound logic in the field and lead to confusion and misidentification and terrible judgment. But the first rule of picking up a gun is never to point it at anything you do not intend to punch a hole through or kill stone dead.

But it can happen, and it does happen, and every hunter knows this, too. In the U.S., from 2001 to 2010, 103 fatalities were reported to the International Hunter Education Association in which the cause of the incident was “failure to identity target.” According to the National Safety Council, the rate of unintentional fatalities involving firearms dropped 55 percent from 1988 to 2008—and experts point to blaze-orange and hunter-education requirements, as well as tighter restrictions on transporting loaded guns, as lifesaving prescriptions. Still, hunting accidents happen, and there is never an excuse.

The drivers were coming. Now they couldn’t be more than 150 yards—maybe 200—through the woods. The deer looked like it was staying put, no matter what. For Cutler, it was now or never.

On Feb. 6, 1975, in the Court of Common Pleas of Somerset County, Pa., Johnston Cutler pleaded guilty to “shooting at and killing a human being in mistake for deer,” a violation of Pennsylvania’s Game Law 825(c). The trial was brief. The court records comprise a short 23 double-spaced, typewritten pages. The facts were laid out clearly: Cutler spotting movement in the timber as the drivers approached, the particulars of Walter Witt’s makeshift blind in the hemlock boughs, the stump that blocked Cutler’s view of Witt’s torso and his blaze-orange vest, the terrible confluence of poor choices that led to the fatal shot. Cutler admitted guilt.

Even in her grief, Cathaleen Witt expressed to the young man that she bore him no ill will and forgave him for the deadly mistake that took the life of her husband.

Cutler was sentenced to three years’ probation, was ordered to pay $1,000 compensation to the victim’s family and the $13 cost of the prosecution, and forfeited his Pennsylvania hunting license for 10 years.

Walt’s Place

_By now the boys had long since grown tired and cold. Their boots—black rubber galoshes they wore for sledding—were no match for the chest-deep snowdrifts. Mark backtracked to his grandfather’s house, but Dan stuck it out longer. On the hike in, he and Mark had quarreled about the fact that Mark got to carry a rifle on his very first deer hunt, whereas Dan had had to wait a couple of years before he was allowed such a privilege. Dan was determined to outlast his brother but now, shivering, he could take the cold no longer.

Dan stood up and followed his own tracks uphill where the snow was even deeper. His father’s trail continued on, and Dan struggled to place his boots in the deep tracks. When the trail turned down a steep slope, Dan knew he’d never make it back up the hill. He stood in the woods and he called for his father, but the deep snow, the dark timber, and the dripping melt swallowed his cries. He turned around. His father would understand. He headed back to his grandfather’s house._

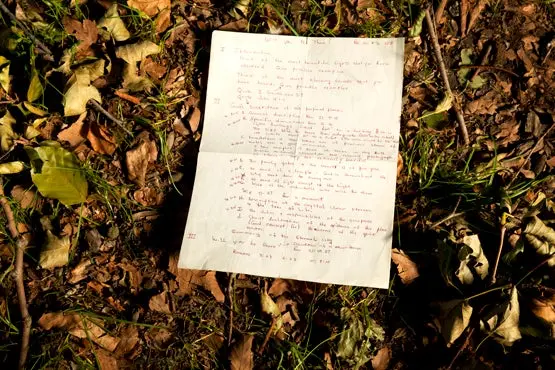

Dan’s shout from the woods brings a catch to our throats. Mark passes me at a half run. The ground falls off more steeply as I stumble over mossy logs; blanketed with 3 feet of snow, this would have been a tough slope for a kid to climb indeed. Then, as the terrain flattens again, I see the first of the big hemlocks, and behind them the darker woods that form an interior edge deep in the forest. Dan is standing beside one of the largest hemlocks we’ve seen all day. Mark is down on his haunches, under the lower dead branches that droop toward the ground. Stuck into the trunk are two reflective thumbtacks, old and rusty. Some hunter marked this spot, marked this very tree. Any deer hunter worth his salt would know: This is the place to shoot a buck.

Mark finds my eyes. “This is the place,” he says. “This has to be it.”

He turns to Askey: “Where was Cutler standing? What would he have seen?”

Askey’s face is ashen. The drivers would have been moving below us, he says, away from the creek. He remembers going back the next morning and replicating the crime scene with another officer. If this is the tree, there would have been another across the slope, to the right. From there, Cutler would have watched the woods, deciphering every twitch of every bough.

Maybe 15 minutes after turning away from his father’s snowy trail, walking toward the house, cold and alone, Dan heard a single rifle shot ring out in his dad’s direction. The sound was unmistakable, one of those two-part shots—pa-THONK!—that occurs when a bullet hits something. Dan’s heart leapt with excitement: Dad just got a deer!

Mark is at the base of the hemlock now. He shifts his body, pressing his back to the tree, trying to conform as closely as possible to what he imagines was his father’s pose in those last moments of his life on earth.

“Is this about right?” he asks. “He would have been facing this way?” Mark shifts his legs so that a rifle might rest across his thighs. He swivels his head right and left. Askey and I say nothing.

“This should be it,” Mark says. “This must be it.”

The drivers would have been close. The deer would have looked like it was staying put, no matter what. Now or never.

Mark weeps quietly at the base of the hemlock, his body mostly hidden from view, only the rise and fall of his shoulders suggesting the cadence of his sobs. “This is what Cutler saw,” he says. He reaches up with his right hand and grasps one of the hemlock’s lower dead boughs, a thumb-thick branch that forks into shorter and shorter lengths like an antler. He pulls it down a few inches, then releases it to dance and bob directly overhead. “And then he shot Dad.” He watches the branch until it no longer moves.

“This is as close as we’re going to get,” Mark adds. “Right here.”

Dan and I exchange a glance. Mark gathers himself, then gets to his feet and takes a few steps from the hemlock. The woods are silent. No one knows what to say. Except for Mark. He turns to Askey to speak of the verity he lives by.

“O.K. If it were you that day, what would have happened?” His glasses are in his hand, and he wipes his eyes with the back of a sweaty forearm. For a moment I’m unsure what he means, but only for a moment. “Do you know where you would have spent eternity?”

If ever a man could be forgiven for taking a moment to himself and putting up an emotional wall against the world, it is this man at this time and place. But Mark Witt is the son of Walter DeSales Witt, and he will not let pass an opportunity to speak. “Would you like to know for sure?” he asks, leaning away from the hemlock tree, toward Askey, his red-rimmed eyes softened by a small smile. “You can. You can know. I can share with you how.”

The bullet was a .32 Winchester Special, and it entered Walter Witt’s forehead just above the right eye, just below the gray-brown ruff of the fur hood the coroner’s report would describe as a “Fur lined Head Dress,” and just above the black stripe of his thick, dark sideburns.

Fathers & Sons

This is the hard time. Winter and snow. Family and Christmas. The best of times for a hunter, of course, but in some ways the worst days of the year for the Witt boys. When Walt was shot, there were already presents under the Christmas tree. The funeral was held two days before Santa arrived. Even for these brothers, for whom Christmas is a time of celebration, December brings an upwelling of difficult emotion. “We can ruin it for our families, we know that,” Dan says. “Christmas is our wives’ favorite time of year, but for us, it can be…horrible.”

This year, though, there seems to be more light on the path ahead. I spoke with Dan in mid October, a few weeks after bow season opened in the Virginia Blue Ridge. His elk trip had been a bit of a bust—too hot, too rainy—but he took his son Hunter for the first time, and had a chance to hand out a few Mistaken Identity tracts.

“I’ve been thinking about Moses wandering in the wilderness,” he told me. “And Abraham being asked to sacrifice his son, and the stuff David went through. Things were put into their lives that God didn’t bring to fruition for years and years. As Christians, we are called to share our faith. This just happens to be my story, and I’m just starting to understand that I don’t know all of it. Mark and I just have to be open to what God might have in store.”

For now, there are presents under the Christmas trees in Lynchburg, Va., and Huntsville, Ala. Outside the leaves have fallen and the deer are settling down after the frantic weeks of the rut. At home, the brothers are redesigning their inspirational pamphlet with updated photos.

“I keep telling Mark,” Dan says, “that we have to have some good photos, and those little Alabama bucks of his don’t count.”

In two months, they will visit the very church where their father was to preach the day after he died. They will step into the pulpit and tell stories about hunting, about their father, about the faith that sustains them. They will talk about the bullet that changed everything, except for those things that are eternal and unchangeable. It will be a difficult path, but they will walk it willingly. One step at a time. Down a trail made easier by the tracks of their father.