This story was first published in the December 2006–January 2007 issue.

Part I

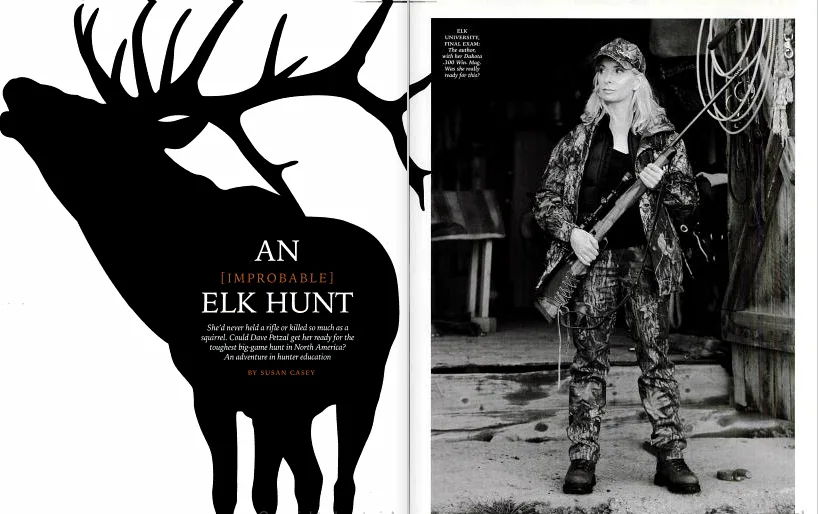

IF YOU HAD ASKED ME a year ago, “So, when’s the elk hunt?” I would have been certain the question was meant for someone else. Because the two key words in that sentence-elk and hunt-meant nothing to me, and when combined spoke of blood and guns, and those were things I didn’t spend much time with. I’d seen an elk once, but that encounter took place on Main Street in Banff; it was a tourist-addled nuisance cow looking for handouts of Cheetos and hardly a majestic ambassador of the species. Hunting wasn’t part of my upbringing, at least not the type that results in homemade jerky. As for rifles, I’d never held one.

But then at a cocktail party last June, hunting entered my life in an unexpected way. It happened during a conversation with Sid Evans, this magazine’s editor-in-chief. As the crowd milled around us and the canapés were passed, I described my new infatuation with spearfishing. Stalking dinner felt surprisingly satisfying. I told Sid, and of course he understood. What was it like to go after something bigger, I asked. Did you have the same primal feeling, but amplified? This idea interested both of us and within minutes the gauntlet went down: Could Field & Stream take a hunting know-nothing, a gun ignoramus-in other words, someone like me—and send her on one of the toughest hunts in North America? Specifically: If the correct efforts were made, the appropriate expertise recruited, could a person go from never having laid eyes on a .300 Win. Mag. cartridge to making a 300-yard shot on an elk? In a matter of months?

The next morning Sid e-mailed to see whether I was serious or “was that just the beer talking?” Elk hunts are brutal, he cautioned. The Rocky Mountain elk fires on all sensory cylinders—smell, hearing, vision—and has an almost eerie knack for staying one step ahead of its pursuers. Elk hang out at high altitudes, in crags and gullies and dark folds of timber, in steep and slippery places where humans fumble around at a disadvantage. Elk hunting would be a commitment. A large one. I would need to learn every nuance of the animal from scratch. The hunt would require peak fitness levels, so that running around at high altitudes was, literally, no sweat. I would need to become a very good shot in a very short time. The magazine would understand if I wasn’t up for it, he wrote. “After all, I realize that you haven’t killed so much as a squirrel.”

“I’m in,” I e-mailed back. “How soon can I go?” My enthusiasm came from a mix of curiosity and guilt-I eat meat but know nothing about what it means to kill for it. I love animals, but I also know that sentimentalizing nature is wrong. Dying, killing, becoming prey-these things are all part of the game, and to ignore them trivializes life. Bluntly put, the modern relationship to the wild is a fake one. For many, meat is a section at the grocery store. And at Safeway there are no big brown eyes to consider, no blood. Hunting struck me as a more honest approach, and a necessary one if the goal is to understand the true nature of, well, nature. If this seems like an improbably heavy philosophical reason for going on an elk hunt, consider that I was an improbable elk hunter, and on the day I agreed to become one, the improbable stuff was only beginning.

“WE HAVE a fairly limited amount of time to turn you into a killing machine,” David Petzal said as we drove to Camp Fire, a private men’s shooting club in Chappaqua, N.Y. It was a warm Friday in July, and Dave, a laconic man with a salt-and-pepper beard who has been this magazine’s resident rifle expert for 25 years, was taking me to his off-site office for a lesson.

That morning I shot my first target, a cardboard bighorn ram, with a 22 at 100 yards, firing prone, and then kneeling, and then offhand (for purposes of humility). Dave has a slow and deliberate way of speaking and a way with language that is dryly hilarious, and he delivered instructions in a courtly drawl. As he moved through the basics; the importance of inhaling, exhaling, and then squeezing-not pulling—the trigger, of relaxing, focusing, and keeping steady hands; we both noticed that mine were shaking. A lot.

“Do you drink coffee?”

“I’m afraid so. The stronger the better.”

He looked at me and shook his head. “Caffeine is not your friend. How much do you weigh?”

“I don’t know. About 105 pounds.”

“Think of yourself as 105 pounds of inert matter. With a trigger finger.”

The .22 felt light, the gun equivalent of training wheels, and it fired with an insubstantial pop, but Dave was testing a beast of a weapon, a synthetic-stocked 338, and its booming recoil was a reminder of what lay in store. My serious gun, the elk-dispatching one, was a magnificent Dakota Arms.300 Win. Mag. rifle borrowed from its owner, Paulette Kok, a friend of Dave’s. Its stock, handcrafted from a blank of English walnut, had been shortened to 12 inches. The Dakota was elegant and lethal and sat imposingly on the rack. To be honest, it frightened me.

“SLAM THAT BOLT HARDER! Abuse it!” I was lying on my stomach, shooting the 22 at a fluorescent orange gopher. When hit the steel target made a bright pinging noise that I liked. Dave felt I wasn’t being authoritative enough with the action. He wanted to hear it snap open and shut smartly and see bullet casings flip into the air. “Use your palm,” he told me. “Stop grabbing the bolt with your fingers.” By now, my third lesson, we had ranged farther afield, driving another 60 miles north to Tamarack, a manicured hunting club in New York’s Dutchess County.

On this range I could practice 300-yard shots by climbing a hill and grazing the top of a cornfield. It seemed impossibly far. “You should be able to make it,” Dave said firmly. “The mistake people make is not trusting their rifles. These things are deadly accurate from a long way off.”

For the time being, 75 yards was challenge enough. Today I would warm up with the 22 and then move to the bigger gun. After a 30-minute session of small-caliber gopher abuse, Dave handed me three-300 cartridges, throw his pack down, and put on earmuffs. The Dakota had a heft and a certainty about it, and as I lay prone, pressing my check along the stock and adjusting the scope. I almost felt comfortable. Breathe, exhale. Squee. BOOM! The gunshot felt smooth, a profound bass explosion with a silky kickback and unspeakable power. My legs jerked in a spasmodic froglike gesture. It wasn’t a very pretty demonstration of form, but I had managed to hit the target in a reasonable spot, and Dave seemed to have faith.

“You flinched,” he said. “But I’ll take it. You’re 105 pounds of what?”

“Inert matter.”

As the summer passed, Saturdays at Tamarack became routine. It made for a long day-two hours on the train, another hour in Dave’s truck, two hours on the range, and then back again—but I was seeing results. My hunt was set: October 30 in western Colorado, a state with a healthy population of 30,000 elk. Over the weeks I shot and shot and shot and began to rend paper in a more consistent manner. Perhaps I had become a line cocky, or perhaps I was simply being careless on the day I split my forehead open with the scope. It was a kneeling shot, and the impact rocked me off my heels. Blood ran down my face: I wiped it off and felt the cut, a clean and deep half-moon. Noting that I didn’t seem bothered by the carnage, Dave had nodded his approval, mentioning that when an elk is gutted, the volume of liquid that comes pouring out is “disgusting. With an antelope you’re up to your wrists in blood. With an elk you’re up to your shoulders.”

I SUPPOSE it was inevitable that eventually, when talking about the elk hunt, I’d hit a raw nerve in someone. But I didn’t expect the most hostile response to come from my own brother, no stranger to a good hamburger. On Labor Day weekend I’d arrived at the family cottage in Ontario’s lake country with a bandaged forehead and stories about learning to shoot. This didn’t sit well with my brother, our conversation started out testily and deteriorated from there. “I just don’t believe in hunting,” he said, crossing his arms and glaring.

I’d heard this line before, and often from meat eaters, not all of whom recognized the irony. My question to them was always the same: Would it be a problem if I bought elk steaks at the store? For that matter, what about ground beef? Commercial meat producers feed hundreds of animals per day through machines with names like the Belly Ripper, the Hide Puller, and the Tail Curter, and though the slaughterhouse cows are intended to be dead by the time they meet these grisly renderings, often they are not. To cat meat and then denounce the elk hunt was hypocritical, but there was no budging him. The argument ended bitterly as he and his wife left, packing up their DVD of nature photographs from a recent hiking vacation.

“I hope that elk’s scream haunts you for the rest of your life, my brother had said as he’d left. Those words echoed in my head. Such furious anger from someone I loved caught me off guard. It seemed unfair and misplaced. Killing is the most profound act imaginable, but in centuries past, it wasn’t optional if you wanted to survive. And even now, while others do the dirty work, out of sight and mind and conscience, that predator DNA ticks on inside us. What I was proposing to do here was perform the necessary act of getting my own food, rather than subcontract that task to a middleman.

Back in New York, I e-mailed Dave about the family dustup, and when I arrived at the train station that Saturday, he greeted me with a wry smile.

“So now you’re seeing the other side of big-game hunting,” he said. As we drove north to Tamarack, he described an altercation he’d had once in the Johannesburg airport.

“I had just checked my guns back out from the police and some middle-aged lady marched up to me with smoke coming out of her ears and said: “You’re going hunting, aren’t you?

“‘Yes ma’am, I am.’

“‘What are you hunting?’

“‘Eland’

“What’s an eland?”

“’It’s the largest of the antelopes and it’s a beautiful silvery gray with gentle brown eyes and heavy trailhead spiral horns,’ I said and then lied: There are hardly any left and so I’m going to kill one for myself before they’re all gone.’” He paused. “And as she turned beat red, I said, ‘That’s what you wanted to hear, isn’t it? Now kindly go away.’”

I knew that Dave was trying to teach me more about hunting than the mere mechanics of shooting. He’d described how it feels when the animal goes down, what it means to actually end a life. During these conversations I’d felt bluff and full of adrenaline, untroubled by potential remorse for the elk. But Dave, with his decades of experience, was more sanguine: “Any of three things will happen when the moment comes,” he told me. “One, you’ll pull the trigger. Two, you’ll get buck fever and freeze. Three, you’ll decide you’re unwilling to shoot. Not from panic, but from a conscious choice.”

The date was September 10. Summer was sliding by, hunting season was around the corner, and even the trees had a brisk fall energy. I picked up my rifle. Lying prone, I emptied the magazine and killed the paper elk three times. “Very nice,” Dave said and turned to fire off a few rounds himself. He was testing a gun that he appeared to like. It was black and sort of cruel looking with none of the warm woodiness of the others I’d seen, but something about the way it shot pleased him, and at that moment I realized that rifles, like high-end sports cars or fine wines, each have a unique personality. I felt that this was especially true of the Dakota-1 was fond of it beyond reason. Yet even though the gun and I were having a lovely relationship, it was never a small deal when the 300 went off. It was loud but also percussive, and I felt its reverberation in my sternum, underneath the center of my chest, somewhere in the vicinity of my heart.

PART II

Smith Fork Ranch sits like a jewel in the West Elk Wilderness, 100 miles southwest of Aspen. This is country that can only be described as nature showing off: white-topped mountains towering on the eastern horizon, verdant valleys to the west, piñon-studded mesas to the south, lush rivers swirling through all of it, and canopies of aspen turned alchemically to gold.

The ranch’s buildings—several log structures, a barn, a riding ring. and four one-bedroom log cabins-were so in tune with their surroundings that they might as well have sprouted from the ground. In 1974 Smith Fork’s owners, Marley and Linda Hodgson, restored a venerable but fading guest ranch, enlisting local artisans for every part of the job, right down to the light fixtures. The result is a five-star retreat that’s deeply rustic, but the sort of rustic that involves a choice between 15 different kinds of single malt Scotch.

On the evening I arrived I sat with the Hodgsons in the ranch library. nursing a glass of tequila and looking at the head of a soulful-seeming 6×6 bull elk. A fire roared beneath him. Though tomorrow would be spent horse packing to Smith Fork’s 10,000-foot camp in the West Elks, I was thinking about how much I wanted to stay right where I was, shooting at elk from the porch perhaps, when the door opened and two men in cowboy hats came in: my guides. Levi Kempf, 26, was fresh faced and blond with a shy smile. A seasoned hunting guide, he also ran the drainage ranch’s flyfishing programs. Chuck Gunther. 41, Smith Fork’s head wrangler, was the kind of authentic cowboy that casting directors dream of. He had deep-set eyes, dark hair, and a lavish mustache, topped off by an imposing black Stetson and a black bandanna at his throat.

Over dinner they explained that Saturday was the first day of Colorado’s second rifle season. There are four such seasons in a year, each a weeklong opportunity to fill a tag. For weather reasons the second and third ones tended to be the most popular, and both men mentioned that tomorrow, Friday, would be a frenzy of hunters jockeying into position for the opening bell. On the way up the mountain I’d see all kinds, Chuck explained, from do-it-yourselfers whose gear was patched together with duct tape to experts whose deployment was less a sporting endeavor than a military campaign.

I could feel myself becoming hyper with excitement and wanted to go back to my room to repack my gear for the seventh or eighth time. “Make sure to keep your hunter-safety card and permit accessible at all times.” Chuck advised, explaining that the local game warden was a zealot with an uncanny knack for showing up when least expected. He was even known to have set up roadblocks for illicit elk, the way others might to ensnare drunk drivers. I immediately nicknamed him “The Enforcer.”

“One time he asked to see my fishing permit twice in the same day, on the same stretch of river.” Levi said. “We will meet him.”

MORNING WAS PERFECT: Bright skies and crystalline cold. Gun? Check. Bullets? Check. Extra set of long underpants? Check. Check, check, check. Check to make sure your headlamp is working and your binoculars are clean and the blaze-orange vest and hat are tucked securely in the duffel. Check to make sure you have enough contact lens solution. Because there were no convenience stores or handy supply depots where we were going.”

I looked out the window of Smith Fork’s horse trailer as it rolled down the dirt road toward the trailhead, kicking up clouds of dust. As we approached the gateway to the higher elevations, the players began to emerge There was a battalion of trucks and a circus of ATVs, men in camo-and-orange-bedecked everything, tents with chimneys in them, women organizing provisions and tending fires and shaking out tarps. There were Winnebagos and dogs and mules, and horses being coaxed out of trailers. The whole place thrummed with the energy of a major sporting event. This was big. I thought to myself, watching the scene. This wasn’t just fun in the woods or a way to obtain meat. This was something more.

Levi and Chuck ran their operation like a Swiss train, unloading four horses and five mules and then loading them up with boxes, duffels, packs, panniers, canteens, and coolers. As they saddled the animals they cracked jokes about nearby hunters whose horses were strewn with stuff, packs slipping off their tail ends. One horse had a pair of tennis shoes slung over its neck.

It was past noon by the time our convoy hit the trail, the Smith Fork River running alongside us. Levi, Chuck, and I were accompanied by the ranch chef. Nick, an artfully tattooed guy in his mid-20s. I was riding Ute, a smallish gelding with a scraggle of a mane. Ute did not have a winning personality. He was known for being off by himself in the barnyard, staring fixedly at one particular wall. As I had climbed into the saddle, he’d bowed his head low with resignation but at the same time pulled his ears back, foreshadowing trouble. It was clear from the start that Ute had the lightest load and the worst attitude.

All around us humans and horses picked their way across scree fields and catwalks, up to the high country. We wound our way up and up and up: thin white stands of aspens towered above us as though we were riding through a box of drinking straws. Along the way we encountered every kind of terrain imaginable: black, sucking mud, rivers of loose rock, logs and grass and heavy dirt, progressing to snow and ice. Throughout all of it Ute registered a lack of enthusiasm. His tactics swung between stopping cold for no reason, and speeding up to jam his head into the butt of the mule in front of him. The mule responded by issuing a staccato stream of farts.

As the hours went by-four and then five-the crowds thinned and we found ourselves alone. “Most people don’t come up this high because of the work involved.” Levi explained. The moment he said it, however, a large black horse ridden by a large bespectacled man appeared on the switchback above us. Both horse and rider had a purposeful air. Chuck steered our group to the side of the trail. Levi, riding behind me, said, “Get your permit out. We were being pulled over, in the unlikeliest of places, by the Enforcer.

In a beautiful way this was predictable. Above all alone guy patrolling a vast swath of mountainous terrain has to be crafty. He can’t survey the entire area; he can only hope to be a threat and to catch the most egregious behavior. Offenses involved people affixing their tags to other people’s animals, haplessly shooting a cow instead of a bull, or mistaking a spike yearling for a legal 4-pointer. Recently. someone claiming deeper confusion had even plugged a reintroduced moose.

The Enforcer, whose real name is Doug Homan, has been patrolling the region for nearly a quarter century and knows the land accordingly. Chuck greeted him and introduced me as a Field & Stream writer, whereupon he immediately asked to check my paperwork. As he unfolded the tag to check for t’s properly crossed, i’s dotted, I mentioned that this was my first hunt, as though that wasn’t completely obvious.

“So you’ll write about how you were checked,” he said, handing the tag and the safety card back to me. “You’re hunting Curecanti? They took some bulls out of there first season. He smiled, and the sun glinted off his glasses. But there’s probably a few left.”

THE HIGH CAMP stood tucked in a snowy slash of pine, three white canvas tents and a matching outhouse. Though I had been told to expect snow at this altitude, the sight of the drift-covered tents was disconcerting. My legs shook from the long ride and Ute’s shenanigans, but there was no time to think about it because less than an hour of daylight remained to scout our surroundings. A sharp bluff rose behind the tents, one that I hoped we wouldn’t have to climb. Levi immediately charged up it. I followed; 10,000 feet and I could feel every one of them. At the top, the canyon rolled westward in the rich light, and on the far horizon we could see the mysterious edges of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, America’s deepest gorge.

Our vantage point was a small promontory from which you could look down on all of it into the folds of mountains and hillsides and drainage cuts. Directly below us several game trails merged—a three-way intersection. “They’ll run below just in us,” Levi said. It was a beautiful setup, made more so by the fact that less than 600 yards away three groups of elk stood foraging on the top of a rise, looking as peaceful as an Audubon painting. In the foreground, a 6-point bull grazed in profile. He was bigger than I’d expected, more Clydesdale than pony, and his pale buff coloring gave him an almost ghostly appearance. I kept my binoculars trained on him for every last drop of daylight, as the shadows dissolved and the coyote echoes began.

THERE IS no sleeping in on an elk hunt, especially not on opening day. The wakeup call comes mercilessly in the frosty predawn, and when Levi rattled the side of my tent, it sounded like gunshots. All over the mountain. come sunrise, the game was on.

Chuck was uncharacteristically silent during breakfast, eating his eggs and staring at the wall of the mess tent. Afterward, Levi and I headed to our promontory. “What’s up with Chuck?” I asked.

“He’s on a mission.”

“What’s that?”

“To find the horses.”

I stared at him. During the night, apparently, the entire four-legged crew had made a break for it, one trampling down the fence, the others following. This wasn’t good, nine elk-size animals running around the mountain on opening day without so much as an orange bandanna between them, and I instantly envisioned Ute as the ringleader.

“Will we get them back?” I asked.

“I think it’s kind of an all-or-nothing deal.”

Dawn was in full swing by the time Levi and I reached our spot, so there was enough light to see the spooked herd of elk cantering below us, white rumps flashing through the pines as they charged up a 45-degree pitch. Levi whipped out his binoculars, but in a second the animals were gone.

“Hmm, I don’t think there were any bulls in that group. Looking in the direction of the vanished herd, he added, “Those elk were definitely spooked by something.”

BOOM! The gunshot came from a ridge to our right. Silhouetted against the sky, a tiny orange-clad figure raised his rifle. BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! Levi and I looked at each other. Someone was a very bad shot.

We hunkered down behind a pair of aspens, and I settled onto the frozen ground with the Dakota braced against my knee. We sat in that crusty patch of snow, sat and waited, sat and then sat some more, glassing the valley. Nothing seemed to be stirring, not birds or bugs or mice or any signs of life at all. By now the fleeing herd would be three valleys away and counting. Was that it? I wondered. Were they already gone, scared out of the canyon? It felt intensely frustrating: all we could do was sit and wait and hope that some hapless elk in this 176.000-acre wilderness blundered into our 300-yard shooting zone.

Before arriving here I’d read that the odds of success on a first elk hunt were approximately 16 percent. The statistic had seemed unduly pessimistic to me, especially since I’d been here less than 48 hours and had already seen a dozen of the animals. But when the bell went off and hunting season legally began, the woods seemed to have emptied out. Suddenly, it was easy to imagine an entire week going by without seeing so much as a single set of antlers.

“This seems heavily stacked in favor of the elk,” I whispered to Levi.

“I was just thinking that.”

Hours went by, body parts began to mutiny. By 11:30 my hands had become so cold that I couldn’t hold my gun, let alone aim and shoot it, so we climbed back to camp for lunch.

The rest of the day was spent sitting on a damp log in a mossy grotto that lacked even a sliver of sunlight to warm things up. The light was muted, almost spooky, with pale shafts falling between dark spruce trunks. Three mule deer slipped through the shadows, giant ears swiveling around like satellite dishes before they pogoed into the gloom. So this was hunting. I’d learned to shoot but I hadn’t learned about this, about the solitude and the sheer numbness of waiting about the fast wash of adrenaline when any twitch of activity broke the stillness. It seemed to me now that the most familiar images of hunting—the gunshot, its aftermath—are the least representative. Hunting was a far more nuanced experience. It was about letting your rusty animal senses out for a romp. And even if that involved eight hours of sitting motionless in a bush, it was still the most seductive reminder that at the end of the day, we are unrepentant carnivores.

AT THE HIGH CAMP, dinner was epic. Up here, the body’s caloric requirements resemble those of a blast furnace, and so the evenings were devoted to chow; to working our way through a case of wine and kicking back, listening to one another’s tales. I loved ducking into the mess tent at the end of the day, into its steamy halo of propane while Nick leaned over the stove, working his magic. After a single dinner I got it: Camp life is an integral part of hunting, perhaps the very crux of the sport. It’s the bourbon late at night and the fact that anything tastes memorable when cooked on a smoky single burner and earned by a day in the mountains. It’s the stories and the kinship and the improbable shelter in nature’s wilder spots, the juxtaposition of privation and privilege, each setting the other into high relief.

Chuck had returned with the AWOL animals in tow, and now they were grazing in the reinforced corral. After hearing a summary of the day’s hunting from Levi, he seemed satisfied. “Aside from an utter lack of equine control, things are going pretty well,” he said.

This wasn’t always the case. Things could go very wrong up here, and did. There had been instances of less-than-stellar comportment under pressure: clients taking wild-eyed 1,000-yard shots, for instance, or chattering incessantly in the field. Chuck recalled one young man who’d managed to alienate the entire camp in short order: “There wasn’t anything to him. It was just wind. Retribution, he said, came one night as the hunters rode in the dark, while the Chatterbox held forth, barely stopping for breath. “The guide pulled back a spruce branch and let it fly into his face. On occasion, people hiked with chambered rounds, or got drunk and picked fights. And then there was the time the liquor had mysteriously vanished. Someone had been filching both the clients Scotch and the guides’ beer, and after much dark suspicion in camp as to whom that might be, it was discovered that the cook spent her days nipping away at the supplies. “A very unpleasant woman.” Chuck said. “Of course we weren’t really in a position to fire her.” He stood up and plucked a bug off the tent wall with a pair of needle-nose pliers. “But we did find a better place to hide it.”

Turning the subject to tomorrow’s plans, he mentioned that while he was out capturing the horses, he’d stopped at a nearby deer camp and heard talk of a pair of big bulls that had been spotted in an area known as Lunch Creek. This was a bonanza of a tip, but daunting: meeting these animals on their home turf meant venturing into a steep cut that was one of the least welcoming spots in the canyon.

Hearing this, Levi nodded. “Wherever it takes the most energy to get to the hardest possible place—that’s where we’ll find them.”

Chuck leaned back in his chair. “There are a lot of hunters lingering around the edge of the drainage, but you two need to go right down into it.” Noticing the pained look on my face he raised an eyebrow. “Elk are earned,” he said.

FORGING INTO Lunch Creek was easier said than done. As Levi and I moved closer to the bottom of the drainage, the hillside became steeper and the brush became a wall and any sort of viable passage became nonexistent. There was no getting down there. And furthermore, there was no way to get a 700-pound animal back out. “No wonder those bulls are big,” Levi said, looking over a cliff at the jagged rocks below.

After scouting the neighboring surroundings we decided to head back to the promontory. We weren’t the only ones who’d been there lately: all around our observation post the grass was tamped into elk-shaped depressions, and we stepped around mounds of fresh scat piled defiantly beside them. Levi examined several sets of hoofprints crisscrossing in the mud. “These were made sometime in the last hour,” he said, shaking his head.

Though I’d expected a clever adversary, I was beginning to realize that an elk at the top of its game was nothing short of a phantom. Levi understood this; he had recently bagged his first bull. Though the elk had been taken on Saddle Mountain, only 3 miles from the ranch, the effort that had gone into the hunt had been anything but small

“I scoped him out for a month,” he said, describing how every morning he had observed the animal’s habits through a telescope. “Then, one week before hunting season, I went up there and cut a trail.” Saddle Mountain was avoided by hunters and favored by elk due to a head high carpet of brush. Levi, who was willing to make a Herculean effort, bushwhacked his way to the money spot and waited. Sure enough, the bull returned and was promptly dropped with a double lung shot.

The elk had been traveling with half a dozen Cows, and the animals ran in panicked circles as it lay on the ground. As he approached the downed bull, Levi noticed that one cow in particular just stood there and bawled. The memory of the distraught cow seemed to bother him. “I wasn’t that excited,” he said, frowning. “When I saw how big it was, I just wondered how the hell I was going to get it down.”

He’d radioed Chuck, who came up with his sister, and the three of them field dressed and quartered the elk using a pair of axes. Then, they packed it out. The entire process took almost 12 hours from the time Levi had pulled the trigger.

But after that, all winter, mealtimes were a jubilee of elk. In the nearby town of Hotchkiss, a venison processor called Homestead Market rented out meat lockers. Levi got himself one and filled it. There were elk steaks and elk burgers and elk jerky, elk fajitas, elk tacos, elk in scrambled eggs, and elk meatballs sprinkled into spaghetti sauce. There was a bonanza of meat.

ELK HUNTING can be described in two simple words: Up. Down. When you aren’t climbing, you’re descending. When you’re not standing up. hauling your gear, you’re sitting down, looking up the mountain, down the valley, scanning the landscape for hints of motion. There are days when luck swoops down on you and days—weeks—of throwing up your hands in frustration. There is no comfort zone on an elk hunt. no middle ground, only extremes.

Levi and I began to frequent a small thicket below the promontory. This lookout held even more promise, he felt, because it offered a view of three hillsides within 300 yards. Should an elk appear on any of them, I’d have a shot. There was only one problem with the spot: to get there we had to make our way down a mile-long. 50degree pitch of snow and ice, usually in the dark It was a slow, arduous descent followed by a slow, painful climb out, but after one morning in this new location we’d seen several cows and come face-to-face with a massive mule deer buck that strolled within 10 yards of us before catching our scent and rocketing off.

The object of the hunt, however, remained elusive. In the last light of the third day. I watched a camprobber jay swan-diving from the top of a spruce tree while Levi dozed. I couldn’t blame him. We’d whiffed entirely—again. But in the next instant, Levi suddenly snatched up his binoculars and tapped me frantically on the knee. “Look,” he whispered. nodding at the easterly slope. I looked and saw nothing but a smattering of aspens. “Where? What?”

“A whole herd!”

And so there was. Four hundred yards away. the exact dun color as the hillside around them, eight elk grazed in the dusk.

All cows.

“There’s got to be a bull with them somewhere,” Levi said quietly, binoculars glued to his face. “Get ready to shoot

The cows had no inkling of us and continued to forage, ambling closer and settling 300 yards away. Two spikes appeared in the mix, illegal yearlings with nubbin antlers. For 20 minutes I sighted them like arcade targets, practicing my aim. Where was the bull? Levi and I watched the sorority herd in frustration, until the curtain went down and their silhouettes melted into the hillside.

Waiting another 10 minutes to avoid spooking the group, we shouldered our packs and began the climb home. We didn’t talk. The truth was harsh-wed seen giant bucks and what seemed like every cow in Curecanti. while the deer hunters had numerous encounters with elk and the cow-tag holders sighed at the appearance of yet another pair of antlers. I was thinking about these ironies and listening to the sound of my boots punching through the snow when we heard it: a long and mournful bugle, echoing down from the ridgeline. We stopped and looked up. I’d been told that the noise that bulls make to call their cows was unique and that it made the hairs on the back of your neck stand at attention. No one, however, had been able to describe it to me, and now I understood why.

THAT NIGHT the temperatures swooned and when I poked my face out of the sleeping bag at 4:30 A.M., the cold jolted me awake. A scrim of clouds blocked the quarter moon, and as I stepped outside all I could see was a salting of stars and a fresh dusting of snow. Levi was raring to go. “I want to get down there earlier.” he said. “If possible, don’t use your headlamp.” I felt skeptical about this advice-it was one thing to navigate the icy elevator shaft with a bit of light, and another to climb down blind. “We’ll just go very, very slowly.” he said, but then took off at a fast clip, leaving me trudging behind.

At the top of the steepest pitch, I got scared and clicked on my headlamp. reasoning that I didn’t want an elk badly enough to end up in a body cast, and when I caught up to Levi at the lookout, the dawn was coming. The sitting commenced. Levi clenched and unclenched his hands to stay warm, hawk eyes roaming the hillside. As the pale light bled skyward, the canyon awoke and was silent. Nothing moved through the naked stands of aspen. All morning we sat and watched the stillness, but the herd did not return. At 11:30, we called it.

The climb out of the canyon had become familiar now, a kind of dastardly commute that we loved to hate. Ahead of me, Levi dug into the snow staircase we’d gouged in the ravine. At the top he stopped abruptly and crouched to stare at something on the ground. Standing up, he exhaled sharply. “Look,” he said.

I looked. Two sets of footprints stood out in the new snow-Levi’s boots in front, followed by mine. But there was a third set too, pressed atop ours, dirt still in the tracks: four-pronged paw prints the size of coffee saucers. You didn’t have to grow up tracking in the Kalahari to figure out what had gone on here.

Mountain lion paws trailed down the slope, through the untouched powder, taking a hard right at our trail and tracing my footsteps. Over the course of 30 yards, as the car had crept behind me in the dark, the space between its tracks had tightened—in the way that house cats tend to shorten their strides right before they launch themselves at something. But then, at the spot where I’d stopped to turn on my headlamp. the tracks veered sideways, bounding across the facing snowbank and back into the forest.

Levi and I stood mute, our breath visible in small clouds. This makes sense, I thought, as a chill ran down my spine. I’d been slow and isolated this morning—perfect prey. Hunter, hunting, hunted: They all blurred together in a disconcerting way. Here I was, in full stalking mode, backed (supposedly) by millennia of innate animal instincts, and I’d had no sense of a 200-pound predator padding along only feet behind me. A few hours later, after the evidence had time to sink in, Levi would mention that turning on my headlamp had probably saved my life.

IT SEEMED like a godsend, then, when Chuck announced that the last two days of the hunt would take place in the lower foothills surrounding the ranch, and that we would strike the High Camp immediately and head down. According to Chuck’s wife, Kerry. Smith Fork’s manager, hefty bulls had been sighted through the telescope every day this week. I packed enthusiastically.

And so, shortly. Levi and I found ourselves shoving our way up his old trail on Saddle Mountain. Though the foliage was almost impenetrable, down here the air was warm and the long underwear had been left behind. We settled in behind a scribble of chaparral and waited.

Almost immediately, 600 yards away, a large bull strolled out of a spruce glade. After days of bull-lessness, he looked almost mythical, this lone white animal standing in relief against the trees. He never came closer, and eventually vanished into the forest. I resolved to kill him the next day.

THE HEAT beat down on Levi and me the next morning as we picked our way up Saddle Mountain once again, past bear and bobcat and deer tracks stamped in the mud. A trickle of sweat rolled down my leg: flies buzzed. Sharp brush lined the route at eye level. We reached the clearing below the spruce glade. There was nothing in the vicinity but more silence.

“Let’s head around the other side.” Levi said, after a time. We slipped our way up a muddy half-path, edging along the hillside, and it was here that we found them. A spindly-legged spike was mowing the grass less than 150 yards away. with a large cow beside him. Levi elbowed me. and we pressed ourselves against a rock. We were partly visible but downwind, and the animals didn’t scent us. Slowly, I moved the rifle into position We didn’t have to wait long. Three hundred yards away, visible through the trees, stood the bull we had been looking for. As he ripped up mouthfuls of sawgrass, everything seemed to move in slow motion. Levi spoke in a raspy whisper: “This is it. Wait until he moves out of the trees and then take him.”

It was a clean shot, and just within range.

The bull came out of the trees and posed in perfect mug-shot profile. I steadied the Dakota on a crossed pair of hiking poles that Levi had brought, and for once my hands were not shaking. Everything felt calm. The air felt calm, I felt calm, the elk grazed calmly.

I put my eye to the scope and inhaled. At 4X magnification I could make our details—the bull was midsize and textbook perfect, with 12 lovely points on his antlers. I clicked the safety off. The spike, now less than 150 yards away from us, moved toward the line of fire.

It would take only an instant to squeeze the trigger. Then: a violent explosion, and we would assess the shot. The bull would be down or he would be running the bullet would have done its mortal damage or it would have wounded him, and the tracking would begin. I would have set the process of killing in motion, and then I would have to finish it off. This is what I came here to do.

This is what I came here to do.

The bull raised his head and looked around. I imagined the impact of the bullet; the animal’s body crumpling. Next to me, Levi tensed.

Another breath, another exhalation. Another minute adjustment to the scope magnification. The shot was there. But something wasn’t right. Somewhere between my head, my heart, and my trigger finger, there was a blockage.

I lowered the gun.

Levi looked confused. “He’s going to move farther out of the trees,” he whispered. “He’s moving.”

Above us the sky was a seamless expanse of blue. For a week I had been searching and hoping for this shot, this animal, this moment. For months I had practiced so when it arrived, I wouldn’t blow it. For years I had wondered what it would feel like to hunt. And here at the edge of the experience, I had lost my nerve. How had this happened? It was like climbing to the top of a diving platform and then slinking back down without even trying to jump. In the end, Dave Petzal had been wrong about one thing. I was not 105 pounds of inert matter. I was 105 pounds of warring emotions. This wasn’t how I thought it would be.

I turned to Levi, and now I was shaking, “It’s over.”

“You’re going to get a better shot,” he said, his voice tight with adrenaline. But even as he said it, the bull turned uphill, dropped over the horizon, and vanished into the next valley.

“No, I’m done.”

A gust of wind blew down the gulley, folding back the grass. The cow and the spike had turned away from us and were headed for the trees. Levi and I watched them go.

After a moment, he reached for the radio and hailed the ranch. Kerry answered.

“The hunt is over,” Levi told her.

“We’ve been watching through the scope.” she said. “We saw you; we saw the bull. But did you take a shot?”

“Uh, negative.” Levi said. There was a long silence on the other end. Chuck came on.

“Listen,” he said as the radio crackled. “You did everything right. You were exactly where you were supposed to be.”

“But I didn’t shoot,” I said.

“I know. But you had a hell of a hunt, and that’s what matters.”

I glanced at Levi, who looked dejected and a bit stunned and as though he didn’t quite see the cause for celebration in this whole scene.

“I’m sorry.” I said.

HOMESTEAD MARKET was jammed with carcasses, with deer and elk and bear, their meat packed in snug white bundles headed into lockers and freezers, their heads and hides being shipped off for mounting. Truck after truck swung by to unload animals, and things got so busy that some hunters were turned away and had to find another processor. Death was everywhere, as was blood and all the shards of bone and skin and rendering, but the place felt very alive. It was a building filled with the honest results of the second rifle season, and being there was an oddly comforting experience, one that I believe will help me pull the trigger next time. Nothing was being wasted here. The cycle simply went on—life, death, and everything that happened in between I watched for a time and then climbed in my car.

Was I disappointed in myself? Yes, although people kept telling me that failing to shoot was not the point. Levi had rallied and declared our hunt a triumph. Even Nick had consoled me, saying, “Hunting’s not always about getting something.” But my behavior wasn’t sitting right, and the emotions came in conflicting pairs: regret and relief, disappointment and elation; anger and resignation. I tried to decide whether I’d feel better if my bull had been among those hanging on a hook here. The answer was yes.

As I drove away from Hotchkiss and Smith Fork and the inscrutable Black Canyon of the Gunnison, I looked back and noticed that a mean gray mass of clouds had gathered and was pressing down on the West Elk peaks. A storm was moving in. The high camp would be battened down by snow tonight, the aspens dusted, every sign of elk and mountain lion and human presence erased by morning, as if we had never been there.

_You can find the complete F&S Classics series here

._ Or _read more F&S+

stories._