They call it the “death zone.” It’s a stretch of Mount Everest that’s about 26,000 feet up and is strewn with something like 200 corpses permanently frozen into the landscape

—a warning to other climbers that the air there is not life-sustaining. While extreme pressure and natural disasters can be killers, it’s also likely that oxygen deprivation played a significant role in these folks’ demise. Basically, when you can’t intake more air than you expend, your organs will fail, causing you to faint and possibly not get back up again. With so many serious attached risks, it’s important for those on the climb to know how to prevent altitude sickness.

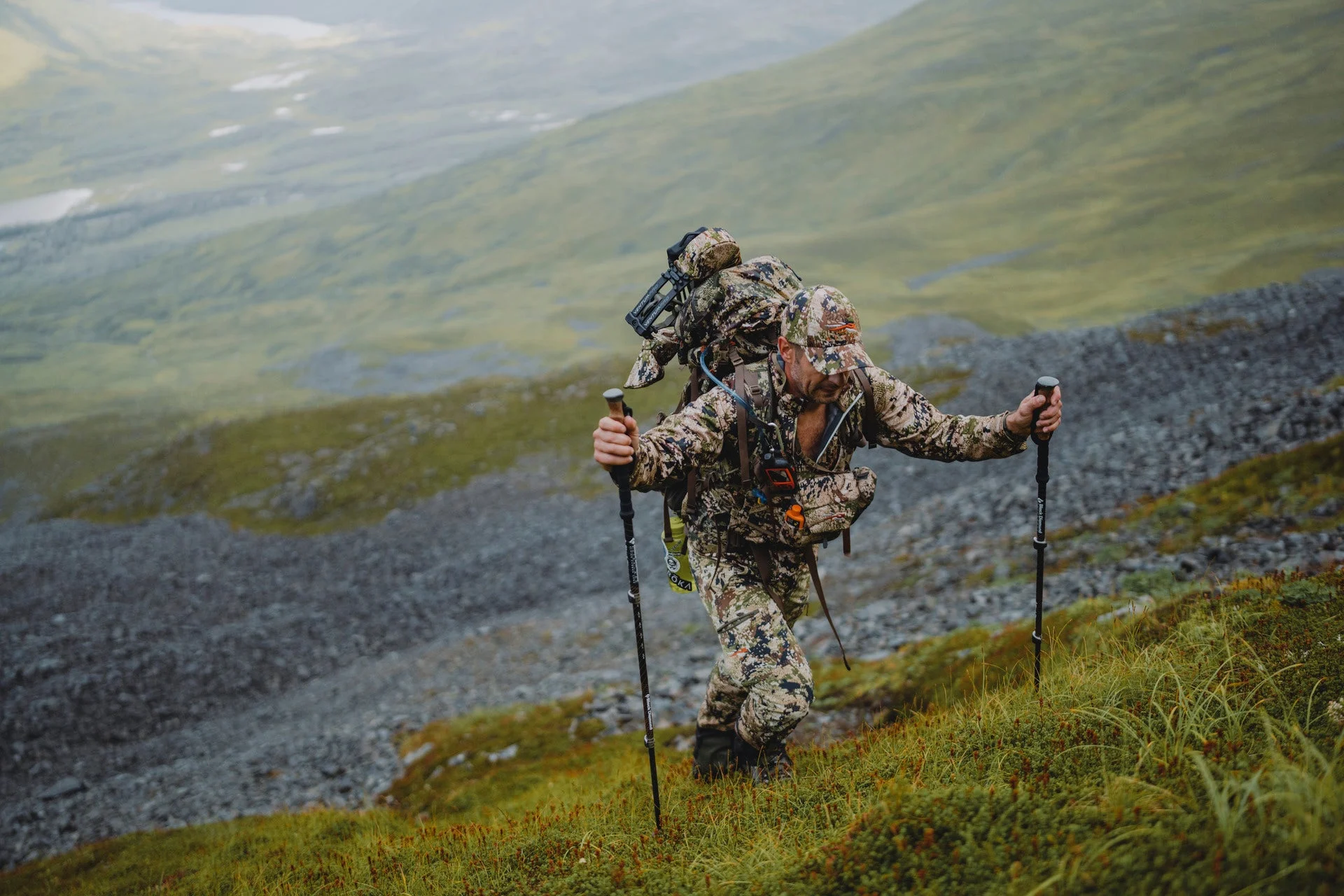

You don’t need to be hiking in the Himalayas to contract altitude sickness. Whether you’re a flatlander going after your first western elk, or a mountain hunter looking to reach new heights on a sheep slam, you need to be aware of the dangers of climbing too high, too fast—particularly if you plan to ascend more than 1,000 feet. Read on to learn more about the different stages of altitude sickness, how to prevent it, and if people can ever become immune.

Table of Contents

What exactly is altitude sickness?

How to prevent altitude sickness, and how not to

Can people become immune to altitude sickness?

What Exactly Is Altitude Sickness?

There are three kinds of altitude sickness: acute mountain sickness, high-altitude cerebral edema, and high-altitude pulmonary edema. SITKA Gear

is caused by the body not having enough time to react to changes in air pressure and oxygen levels that come with increased elevation. And as previously noted, it’s not mountaineers who need to worry about it. Typically, any place that is 8,000 feet above sea level is considered “high altitude.” Doctors and other experts warn that even a slight change—say, flying from New Orleans to Colorado—can necessitate a few days’ adjustment.

To begin with, there are three kinds of altitude sickness: acute mountain sickness, high-altitude cerebral edema, and high-altitude pulmonary edema. Acute mountain sickness, the least severe of the bunch, might be something easy to write off as just feeling a bit sick, or even hungover. Symptoms include nausea, a turned stomach, and dizzy spells that come from sitting up. It’s common and usually self-treatable.

High-altitude cerebral edema is a fancy way of saying someone’s brain capillaries have begun to leak due to hypoxia, or oxygen deprivation. People suffering from HACE can appear drunk, as they will be clumsy, confused, and sleepy. This form of altitude sickness is dangerous enough that requires immediate medical attention, as it can lead to a coma or death.

Meanwhile, high-altitude pulmonary edema happens when the blood vessels in the lungs begin to leak fluid and fill up the lungs. It is typified by shortness of breath and by coughing up frothy, pink fluid. As you might imagine, this is incredibly dangerous and should be cared for by a doctor.

While acute mountain sickness is much less dangerous than the other two versions of altitude sickness, they’re all caused by descending too quickly, and are all treated in more or less the same way.

How to—and Not to—Prevent Altitude Sickness

The earliest signs of altitude sickness can feel like a hangover, so it’s important to not actually be hungover when climbing above 8,000 feet so you can know for sure whether you’re heading into dangerous territory or not. SITKA Gear

Once again, the only way to really prevent altitude sickness is to not ascend too quickly. That’s fairly easy advice to apply if summiting a mountain or going on a hike. If you come from a low-lying place and are traveling to somewhere mountainous, try to plan your trip over a period of five days rather than two. Once you arrive, play close attention to how your body is reacting to the new environment.

Avoid taking sedatives or drinking excessively before bedtime, because being at a high altitude already slows down your breathing. And, as previously mentioned, the earliest signs of altitude sickness can feel like a hangover. So it’s important to not actually be hungover when climbing above 8,000 feet. That way you can know for sure if you’re heading into dangerous territory and need to take some time to acclimate to your new environment.

If you feel the onset of acute mountain sickness and there’s no other plausible explanation as to why, stop climbing immediately. You can take ibuprofen to treat your headache, or get your doctor to prescribe other medications to alleviate your symptoms. But if you don’t take anything and begin to feel better within a few days, your body is giving you the go-ahead to continue on your ascent without risk of further complications.

Sometimes, though, you don’t have a say in how quickly you change altitude. Say you’re flying from somewhere like Florida to the mountains. In that case, you can ask your doctor for acetazolamide, which is a medication commonly used for glaucoma. According to the Center for Disease Control, this drug can make the process of acclimatization take only a single day, rather than four or five, by stimulating ventilation. The idea is to begin taking the pills 24 hours before arriving at your destination, and then take it for another two days once arriving.

Additionally, many people are under the mistaken impression that drinking lots of water is a good way to prevent altitude sickness. The two are not actually related. However, the symptoms of dehydration are quite similar to those of acute mountain sickness. It’s important to keep your fluid levels up so as to not confuse one for the other.

Can people become immune to altitude sickness?

A person’s tolerance for a lack of oxygen does depend, in part, on fitness levels and conditioning. That’s to say, people who live at a high altitude may be less prone to acute mountain sickness, but they’re not immune. According to a scientific survey

conducted in 2006, about 43 percent of sherpas who participated had previously experienced one symptom when climbing significantly higher than their resting altitudes.

Conversely, studies show that exposure to extreme altitudes can cause permanent changes in the body. The brains of professional mountaineers will sometimes shrink as they lose brain cells, which causes cognitive deficiencies. In fact, a 2008 article in Scientific American detailed a study by a Spanish neurologist who took MRIs of 35 climbers with high-altitude climbing experience and found brain damage in almost all of them, even if it was outwardly unnoticeable.