GREG MAYNARD bows his head in prayer. It’s about an hour before sunset on a Friday in May, and the president of the ProSport Kennel Club is standing inside a clubhouse in western Indiana that looks like no place of worship I’ve ever been to. There’s a mural of two treeing walkers howling at the heavens alongside taxidermy and dusty trophies. Everything else is bare plywood—a low-ceilinged tinderbox plated with corrugated steel. Europe’s great churches were built to last forever, but this place clearly seems built for the impermanence of tornado country. The nearest town—population 1,100 or so—has just been laid to waste by a twister. It happened so recently that the local bank’s marquee still reads: #SullivanStrong.

Our hosts at the club put down their euchre cards or stub out their Winstons into plastic ashtrays. They take off their mesh caps as Maynard, the man who brought me here, asks the Lord to keep everyone’s dogs safe.

Members of the hunting club play a hand of euchre. Their choice of drinks tells you it’s going to be a late night. Tom Fowlks

I’ve traveled from Brooklyn to the Midwest to participate in my first-ever raccoon hunt. Until now, I’d assumed that Alabama—the setting for Where the Red Fern Grows and home to the Key Underwood Coon Dog Memorial Graveyard—was the epicenter of the sport. But it turns out that the Midwest is where you can find a raccoon-hunting competition within an hour’s drive in any direction, every single weekend.

Prior to the 1950s, judges in raccoon-hunting competitions would simply watch dogs hunt and decide which one they liked the best. Since then, little by little, the rules have been codified. Then came the cash and prizes. In recent years, only top-ranked hunters could qualify to compete for big prizes, like a truck. So in 2020, Maynard co-founded ProSport to circumvent that requirement. Just about anyone who can come up with the entry fee can join hunts run by ProSport, which bills itself as sponsoring “coon hunts with a good payout.” The tagline is a bit of an understatement. Forget a new truck. Tonight, there’s $100,000 on the line.

Rules of the Game

Maynard, who is 48, has already told me over the phone how the competition will work. First, he’ll separate the 32 participants into eight casts of four. Then each group will head to a different place in the woods, where they’ll cut loose the dogs. Each hound will be awarded points—100, 75, 50, or 25—based on how quickly it can find and tree a raccoon without killing it. The hunter whose dog accumulates the most points in each roughly two-hour cast will move on to a second late-night cast. Then those winners, three hunter-and-dog pairs in total, will go head to head in Saturday night’s final to decide it all.

Greg Maynard, far right, meets with fellow competitors before the hunt begins. Tom Fowlks

What Maynard doesn’t say, but what immediately becomes obvious upon my arrival in Indiana, is that the culture of raccoon hunting has changed with the influx of big money. After we pray, he explains to me that part of the fun of raccoon hunting is that it provides men like him a sense of community and purpose. They ask each other for loans. They support each other through divorces, or worse. As we head outside, I meet a hunter named Judas Bowling who recently had been diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer.

Maynard introduces us and says, “The doctor told him, ‘Get your affairs in order, son.’” Bowling just kind of shrugs while thumbing a blue Bic and a pack of menthols, but then he becomes visibly upset. Turns out, he’d learned earlier that it would be his last night hunting with his best friend, Apollo. A stranger in Atlanta had just bought the dog for $75,000.

“At least if you pay that much for a dog, you’ll take care of it,” Bowling says. “But that’s just part of it, I guess. He’ll go from sitting in my $500 truck to sitting in satin sheets.” Then the big man starts to tear up.

A hunter’s tools laid out on a tailgate, including headlamp, dog collar, stopwatch, and raccoon call. Tom Fowlks

Talking to the other hunters in the parking lot, I learn that very few of them own the dogs they’re hunting with. Instead, most are running hounds owned by wealthy folks who have also staked them the $6,500 entry fee. If they win, they’ve agreed to split the winnings down the middle.

About half a dozen of the competitors make raccoon hunting their full-time jobs, and almost everyone else here aspires to find a benefactor and go pro, too. “It’s kind of like how in horse racing, the guy who owns the animal isn’t the one on top of it,” one hunter tells me about the business. “These days, you get a different class of people out here who can take their lumps and bruises more easily.”

The sun is burning low and blood-orange in the sky as I jump into Maynard’s truck with a photographer in tow. It’s time to see what these hired guns can do.

One of 32 competitors uncrates his dog for the first of three hunts. Tom Fowlks

Cast of Chaos

Like nearly everyone here, Maynard grew up hunting with his dad. He’s seen photos of himself as a toddler on top of his pop’s shoulders, running around the oak and hickory forests of Ohio. And he wishes his old man could see him now. “I’m doing ProSport for the hunters who are now able to make a living at it,” he says to me as we stand along a rural stretch of road, pulling on headlamps. “It’s not for my personal gain.”

It’s pitch-dark and the four dogs in Maynard’s cast are pulling deliriously at their leashes. At the judge’s signal, they’re cut loose into the night. Within 30 seconds: cacophony. Multiple dogs are barking at once, and they all sound exactly alike to me. But each handler knows his hound intimately. Maynard says out loud that his 3-year-old Walker has caught the first scent of a raccoon, and no one disagrees.

“Strike, Molly!” calls the judge, and we’re off running to find her.

At the judge’s signal, Maynard (left) and a another member of his four-man cast release their hounds into the night. Tom Fowlks

As I fumble around in the dark, trying to decide if I should hold my arms up above the waist-high stinging nettles or down to brace myself for the inevitable fall, the rest of the group becomes tiny, bouncing pinpricks of light that seem to be about a half-mile away. I go with the latter, and my arms are instantly on fire, but I’ve got bigger problems. Maynard clearly undersold the experience when I asked him what I should bring. While everyone else has both a high-end GPS and a local guide who knows every square inch of these woods, I’ve got my urbanite sense of direction. They are also wearing Yoder Super Chaps that have been sewn onto waterproof boots by the Amish out in Pennsylvania. I’ve got on street clothes and Blundstones.

Eventually I catch up with the group where the judge is trying to score Molly. She’s switched to what’s known as a “tree bark,” which has a slightly deeper timbre than the one she first let out. She’s on her hind legs and desperately trying to claw her way up what looks like a thick-trunked maple. Spittle is flying everywhere as everyone shines their lights into the canopy, trying to spot the raccoon. If it’s not there, the tree is considered “slick,” and Molly will score negative points, putting Maynard at an immediate deficit.

Molly trees a raccoon as Maynard moves in. Tom Fowlks

The headlamps we’re using are no joke. They go for about $300 and have various bulbs, filters, and settings, including a laser pointer to help a judge precisely locate treed raccoons. Even though this is a competition, everyone helps look for the glare of the raccoon’s eyes. Eventually, a spectator using a thermal-imaging monocular points high into the treetop at two tiny dots of yellow shining back at us. By the time I manage to see them for myself, another hound has treed another raccoon, which means everyone else has resumed sprinting, and I’m trying to catch up again.

I never really do, but Maynard fills me in on the evening’s main drama when we’re back in his truck. He caught a lucky break after Molly treed the first raccoon. Two of his competitors found their dogs fighting over the same animal—an immediate disqualification per the rules. That left just one other competitor in his first cast. He and Molly won handily with 200 points.

Spectators and even fellow competitors peer into the canopy to help locate the treed raccoon. Tom Fowlks

I’m excited to hear how everyone else’s night went. But that doesn’t happen. Once people get eliminated from a ProSport event, they chug some more coffee or another energy drink and drive 10, 12, or 14 hours straight home. These hunters basically live in their trucks. No one gets the doctor-recommended amount of sleep. And there’s absolutely no time to socialize between hunts.

Maybe it’s for the best. By the time we get back to the clubhouse, I feel like I’m going to pass out. The idea of heading back out for another two-hour ordeal is unthinkable. I decide to go back to my hotel and get some real sleep. I tell Maynard I’ll be fresh for the next night when the final hunt begins. He teases me a little. “I said you’re gonna do a lot of walking, and you said that was no big deal, because you’re from New York,” he says with a laugh. “And look what happened.”

A judge, who will award each hound 100, 75, 50, or 25 points based on its performance, blows a call to get the attention of a raccoon so he can spot its glowing eyes. Tom Fowlks

High Stakes

It’s the second and final night of the hunt, and the other guys give Maynard a light ribbing as they swap their slip-on shoes and mesh caps for chaps and headlamps. Apparently, he got emotional at another event last year where the stakes weren’t even super high. “If he wins tonight, someone’s going to have to drive him home,” cracks Jason Daughtery, who’s also in the final three. The photographer and I climb into Maynard’s truck, and during the hour-long drive to our hunting location, he fills us in on what we missed late Friday night.

“We just got lucky,” he says. “Molly ended up drawing a two-dog cast, so it was one less dog I had to compete against.” They won handily. “Now I’m thinking that I may just win this thing with a little more luck.”

Headlamps shine powerful beams into the night sky. Tom Fowlks

Soon Maynard’s phone is blowing up. Everyone from his wife to people he trounced in the competition yesterday are calling to wish him just that—a little more luck. Daughtery and the other man left standing, Josh Sizemore, are both seasoned pros who do this for a living. But Maynard has never won one of his own big-money events; he works full-time as an estimator for a scaffolding company in Ohio and dreams of being able to hunt full-time.

As the only non-pro left in the bunch, he’s an easy guy to root for. And as we park and prepare to hit the woods, the pressure is hitting him—and out comes the aforementioned sentimentality: “If you win this, you go down as one of the all-time greats,” Maynard mutters to himself. “You’ll be remembered for generations.”

The author gets some help crossing a deep creek while trying to keep up with the hounds. Tom Fowlks

With his headlamp on, Maynard lets Molly out of the metal box in the bed of his Ford F-150. He’s kept her in there for most of the evening so that she wouldn’t tucker out, and now she’s pulling at her leash and raring to go. I’m less excited to be back here than she is, but I have wised up a little since last night. Even though it’s hot and dry, I’m covered head to toe in rain gear and bug spray. As we wait for the judge’s signal, I ask Sizemore what he’s thinking.

If Maynard is excited about cementing a legacy, Sizemore is a stone-cold killer who doesn’t just want to win but wants to step on his competition’s throats. He explains that ProSport competitions are often livestreamed on Facebook, where commenters chime in with what they thought handlers did wrong. He likes to review this footage like an NFL coach would. He spent his morning doing just that from the parking lot of his hotel in Terre Haute. “I was pretty much in control the whole time,” he tells me of what he learned. “But the competition that I’m hunting against tonight is just unreal. Bella will have to have a coon every single time she trees.” The athlete he’s referring to can run 5 miles at a clip. But the most important thing, he says, is that she’s smart: Bella is almost never wrong about treeing a raccoon.

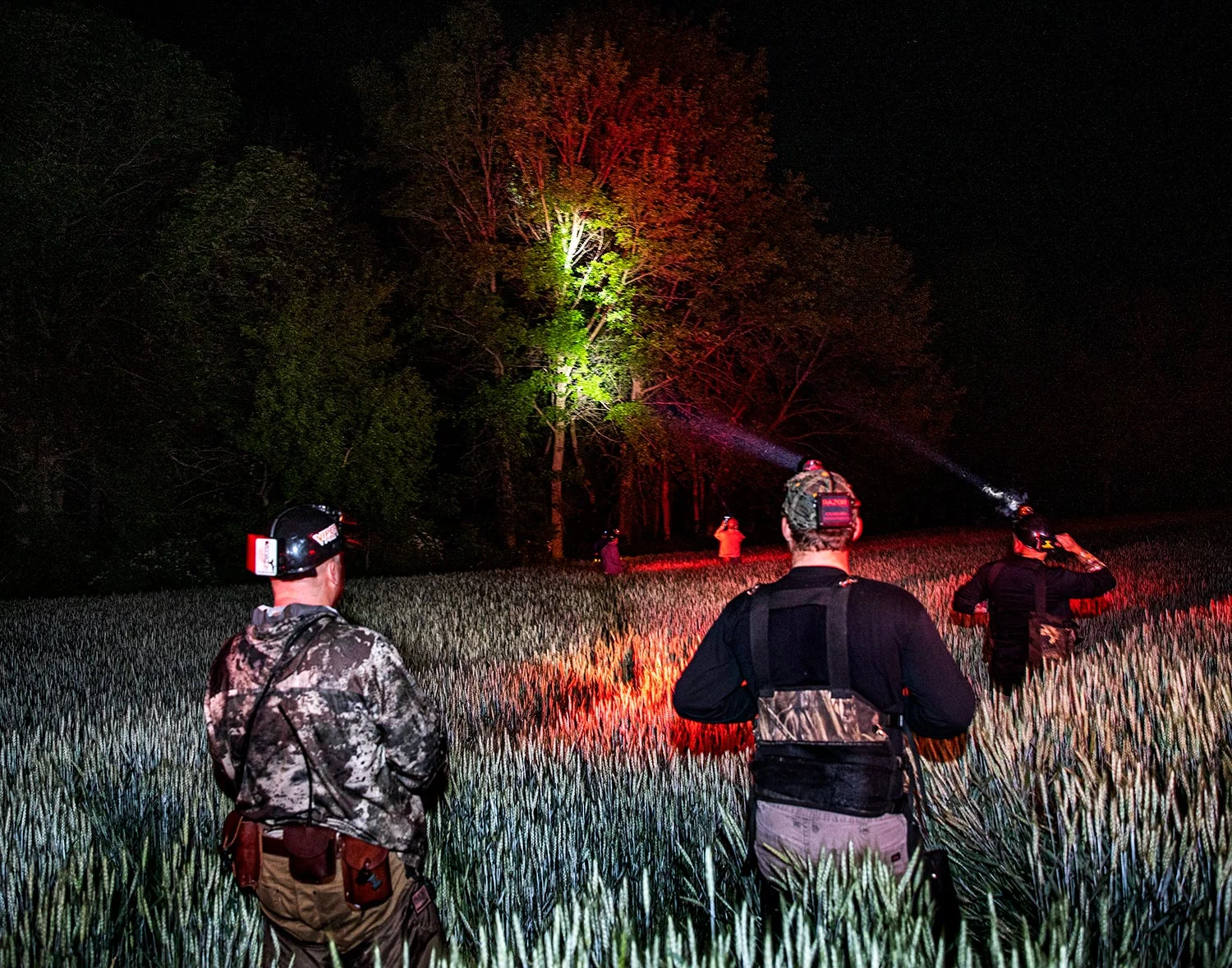

The final hunt to decide it all starts with the competitors wading through waist-high grass. Tom Fowlks

End Game

We all head into the tall grass together without much ceremony. Then the judge tells the hunters to cut their dogs, and they race into the forest at breakneck speed, while we listen for the distinctive bark that means someone’s dog has caught the scent of a raccoon.

“Strike, Bella!” the judge bellows, and we’re off again to see if she is, in fact, always right.

In minutes, we hit a creek that comes up to my mid-thighs. I try shimmying across a downed tree branch, but I’m afraid of getting completely left behind before we even get started. Suddenly, a savior. A spectator who’s come with us to watch the competition throws me on his back and totes me across. This, he says, is what he did when he was teaching his son to hunt. But as soon as we get to the other side, and after I’ve crawled up a steep embankment, the hounds spin around and shoot back across the waterway. This time I don’t make my new friend bother; I just resign myself to running around with squishy socks for the next couple of hours. When I finally catch up with everyone, the judge writes down 100 more points for Sizemore, who now has a solid lead.

Bella was right indeed—but not flawless, as it turns out. When I catch up to Maynard, who is calm and quiet while I’m gasping for breath and pulling thorns out of my rain gear, he tells me that Bella has made an uncharacteristic mistake; she’s only supposed to chase the raccoon up a tree, not catch it.

Maynard releases Molly in the final round. Tom Fowlks

During this entire hunt, constantly trying to catch up to the group, I’ve been thinking of myself as the greyhound chasing the mechanical rabbit that’s forever out of reach. But for Bella to actually obtain the object of her desire is disastrous and could end Sizemore’s evening. Why would his hound go looking for another raccoon, after all, if she’s already got one in her mouth? Maybe Maynard’s little bit of luck has arrived. But then something bizarre happens. Against all odds—and animal instinct—Bella drops the animal to pick up the scent trail of a different one. The competition is still on.

Fellow finalist Josh Sizemore catches up to Bella as she trees yet another raccoon. Tom Fowlks

In the next hour and a half, Molly ends up getting what’s known as a “circle tree,” meaning the judge couldn’t determine one way or another if there was anything up there. “You have to be 100 percent sure that there’s nothing up there before you can minus it,” Maynard explains. But during the time wasted, Bella trees a total of eight animals. According to Sizemore’s GPS, she is miles away looking for another when the judge calls the competition for him.

Maynard hangs his head as we walk back to the truck. Sizemore, meanwhile, is scrolling through Facebook comments on his phone and taking in the congratulations. Although he seems emotionless for someone who’s just won the equivalent of a down payment on a house, one text makes him smile—a message from a guy he plays cards with who’s constantly ribbing him about not having a “real” job. “He’s an older gentleman who makes $30 an hour working for UPS and gives me heck,” says Sizemore. “But now I can tell him I’m making $7,700 an hour.”

Finishing in second place, behind Sizemore and Bella, doesn’t seem to dampen Molly’s enthusiasm. Tom Fowlks

After Sizemore pays his sponsor, he’ll have $46,750 to put in the bank. He plans on taking exactly one weekend off before heading to compete for a brand-new Ford F-150. Then it’s time for another $10K event in Ohio. The life of a hired gun apparently never slows down for long. As for Bella, she’s now officially a $100,000 dog who doesn’t know how to sit, stay, or roll over.

Maynard’s legacy will have to wait. For now, at least, he won’t go down as one of the all-time greats. And as I’ve now come to expect, he’s sentimental about it. “I wanted everybody to remember Molly as being the winner, so she’d kind of be crowned with that title for life,” he says wistfully. “That, honestly, would’ve meant more to me than the $100,000.”

_Read more F&S+

stories._