This story originally ran in the April 2016 issue of Field & Stream.

Jeff Budz turned the Expedition’s engine off and blew a coyote call out over the South Dakota prairie. When he heard the first distant gobble, he took off wordlessly at a ground-covering jog and glassed a distant field edge. Jogging back toward me, he veered down a pine-studded ravine to the right and motioned me to follow. When I finally reached him, he was almost to the top of the ravine wall, waiting for me. I clawed my way up. “Look, dude,” I whispered. “I’m in decent shape for a guy my age, but I can’t keep up with you.”

“Nobody can,” he whispered, not bragging but merely stating a fact. “Just get to me as fast as possible. I want you as close as my pocket on my right side. Keep your head lower than mine. If I make a fist or squeeze your shoulder, freeze. If I point and show fingers, that’s the direction of the bird and how many yards away he is times 10. If I tell you to shoot, come up with your gun shouldered, put the sight halfway up his neck, and kill him.”

I nodded.

Budz pulled a turkey fan from his vest and raised it slowly above the lip of the ravine, looking through the feathers. His hand squeezed my shoulder. I froze. Then he pointed, showing two fingers. “Shoot the one on the left,” he whispered.

Trembling, I rose, saw the two toms at 20 yards, and aimed at the neck of the left one. The gun roared. The bird began to flap away. I shot again, and it disappeared behind an apron of brush. Budz’s head dropped. “I don’t see how…” I mumbled.

“At least you missed clean,” he said. His cheeks bulged slightly with the two calls he carried in his mouth simultaneously—one for sharp yelps and cutts, the other for soft clucks and purrs. He threw a call after the departing birds. And one called back. Budz’s eyes got big. “It’s not over,” he said.

First Impressions

When my editors asked me to join Jeff Budz

on this five-day, three-state road trip, with his girlfriend, Jenny Slaton, and a couple of his pals, I was hesitant. Calling Budz a turkey “maniac” is like saying the Kardashians “like” publicity. I’d never met him, but I knew his reputation as the turkey-killingest man alive. A friend who’d hunted with him said that “he makes your definition of hardcore seem half-assed.”

When I wrote to him with some concerns, Budz responded, “Don’t worry. I’ll take it easy on you.” This turned out to be a lie.

Hearing the tom gobble again after my two whiffs, Budz rode his heels down the 30-foot embankment we’d just clambered up. He looked like he was enjoying himself, as if he were skiing. I slid down in a three-point stance—both feet and my butt.

We chased those two toms for hours and miles on the 2-million-acre Sioux reservation where we’d started our odyssey. Budz would catch sight of them, gauge their mood and direction of travel, and figure out how we could snake along a ravine or follow a finger of woods or belly-crawl hundreds of yards to get in front of them. Eventually we did. And eventually, he told me to shoot again. I was using a Benelli Super Eagle II with a Carlson choke designed specifically for the Hevi-Shot Magnum Blend shells I was shooting. Budz said it could kill a bird out to 70 yards. Maybe that was the problem. Maybe I was just too damned close. Because the tom was only 30 yards away, standing in the open. And I missed again.

Having been asked to hunt with four strangers, I’d hoped to make a good first impression. The first two misses were setbacks, but I was able to rationalize them as hiccups, momentary losses of poise. This third miss made me feel like I was on a bobsled run of failure, gathering speed. I started to dissociate. It wasn’t me who was missing. It was some guy who had rented my body for the day and hadn’t read the manual.

The turkeys, at this point, decided that we should both see other people and flew across a ravine so deep that we couldn’t see the bottom. Budz charged after them. Things that demoralize normal people—a bottomless ravine—energize him. “People always complain that they don’t like hills,” he later told me. “I love hills. You know that metallic taste in your mouth when you’re maxed out physically? I love that taste.”

After only hours in the field with him, it was clear that Budz was the most driven hunter I’d ever met. It would be tempting to dismiss him as a whack job, if it weren’t for his accomplishments. At 49, he’s registered 91 grand slams, each of which involves tagging all four subspecies of wild turkey. That’s more turkey slams than anybody in history and about 40 more than his closest living competitor. When he discovered that there was something called a super slam—killing a turkey in every state but Alaska (where they aren’t present)—he was initially crestfallen to learn that three hunters had already done it. A closer examination, however, revealed that each of the three had used guides. That, Budz realized, meant that the distinction of completing a self-guided super slam was up for grabs. So, over the course of about 15 years—much of it spent living out of his truck, poring over maps, knocking on doors, and eating Power Bars and Fig Newtons—Budz completed the feat in 2014. During one stretch, he killed 10 toms in 10 states in 12 days. He figures he averaged about three and a half hours of sleep a night.

Reaching the Bottom

We descended into the deep ravine and climbed up the other side. It was getting late. We were walking along a flat, brushy hilltop, looking for birds, when Budz grabbed my arm. The toms, 20 yards ahead of us and just coming into view, had no idea we were there. “Shoot!” Budz said. Then he pleaded, “Please shoot those turkeys!”

I shouldered the gun and realized I had two red heads lined up perfectly in my sights. The world slowed. Even I knew this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But whoever had commandeered my body decided that it was a good time to practice flinching. My shot hit the ground 10 yards in front and 10 yards to the left of the birds. Hevi-Shot, incidentally, is devastating on dirt, at least in South Dakota. The turkeys spread their wings languidly and glided down the long hill we’d just scaled, back into the thick woods.

Budz said nothing and walked off a few yards to be by himself. He was facing away from me. His head and torso were bobbing rhythmically, like a man banging his head against an imaginary wall. It reminded me of the TV footage you see of people at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem. A strange thought coursed through my brain. Maybe they’ll put up a Wailing Wall in South Dakota in my honor.

The bobsled run was over for the day. I had just medaled in the Loser Olympics. I felt for Budz. He had done nothing for the past 15 hours but try to spoon-feed me chip shots at wild turkeys. My only part in all this was to aim a stick at the birds and then move my right index finger. That, obviously, had proved too complex a task. I wanted to melt into a little puddle of failure and soak into the ground.

To his credit, Budz handled my meltdown like a pro. He composed himself, told me it was O.K., and even managed a smile before we trudged back to the truck.

This was just the first day.

Jeff’s World

When you hunt with Budz, you enter Jeff’s World, which is a different reality. You get up every day at 3:30 a.m. If you aren’t up by 3:45, Budz will shake you awake. If your motel-room door is locked, he will pound on it until you wake up or the manager calls the police. You’re in the woods before dawn, you don’t leave until after dark, and you will spend most of that time jogging, scrambling, and belly-crawling. You will want to sneak rocks into Budz’s vest to slow him down.

In Jeff’s World, the dominant personality is a teetotaling Christian who is so relentlessly upbeat that, around 2 p.m., when you feel like you’ve been awake for 36 hours, you will want to put a bag over his head so you can leave Jeff’s World if only for a few minutes. When you do fill your tags for one state—if, in my case—you immediately jump in the car and drive hundreds of miles, mostly at night. In Jeff’s World, driving during the day is a kind of sin. That’s time that could be spent doing the only thing Budz cares about, which is hunting turkeys.

As strange and oppressive as Jeff’s World is, you will find yourself liking Budz himself. He’s outgoing and easy to talk to. He is open about the fact that he’s a little crazy. “If I were a kid in school today, I’d be on tons of ADHD medication,” he says. A germophobe who carries disinfecting wipes everywhere, he prides himself on traveling light but cannot imagine life without Chapstick, hand lotion, and Charmin. He’s an obsessive-compulsive who likes things organized his way. When friends want to mess with him on trips, they don’t rearrange the whole truck. They move little things. They put the pen one tray over on the console or a seventh shell in a pouch that had six. “That unnerves him much more because he’s not sure what’s going on,” says Bob Brammer, a friend for 35 years, who is also on the trip.

Did the world’s greatest turkey slayer learn at his father’s knee? Of course not. That guy would have had nothing to prove. Budz’s parents divorced when he was 4. He grew up in Illinois with his mom, a real-estate agent who worked hard to feed Budz and his two sisters. He learned to survive, to be on his own. He vowed never to be dependent on anyone else. Once, he heard a woman who’d been rude to someone explain that she was always that way until she’d had her coffee. Not wanting to be that kind of person, he vowed at that moment never to drink the stuff. Boom. Door closed. On to the next thing.

When I ask Brammer to describe how they met, Brammer smiles and Budz winces. “His mom came to me in seventh grade,” Brammer says. “She said, ‘He talks a lot. He’s going to need a little help getting through school. He’s my only boy. I’ll pay you $5 a week to look out for him.’ I looked him over and said, ‘Make it $10.’ She said, ‘Deal.’”

Budz didn’t start hunting until a friend took him out in college. He killed his first turkey in 1989. “I knew I’d found something,” he says. He liked everything about turkey hunting. He didn’t need anyone else. He could be as aggressive as he wanted, could hunt by his own rules. “I knew I couldn’t hunt like everyone else, though—a day here, or a weekend there.”

He first heard about grand slams in 1993, and completed one the next year. Again, he’d found something. He called turkey biologists in every state for information as he drove. He scoured maps of public land for remote areas. He knew how to talk to farmers, and there’s something about the guy that’s just hard to say no to. He finished up his self-guided super slam in Arizona with a bow-killed Merriam’s tom. I ask why he used a bow, and he says he knew the photo accompanying any story about his feat would be from that last hunt, and a bow would make the accomplishment that much more impressive.

By 2019, he expects to register his 100th grand slam, a number once considered unreachable. But he doesn’t just want to lead the pack in grand slams. He wants to make history.

Getting Hosed

On the second day, with everyone else tagged out, Budz announced that he and I weren’t leaving South Dakota until I put a turkey on the ground. I accepted this with surprising equanimity, either because of sleep deprivation or because there was nowhere to go but up.

It took a while. We got on some birds at dawn and chased them all over creation but never got close enough for a shot. After lunch, we went from one hilltop to the next, calling. Eventually, a gobbler answered a loud yelp from Budz’s box call. We couldn’t see the bird, but Budz took off as if he knew exactly where it was. Glassing from behind a cedar, he spotted two toms and a few hens in a draw about 500 yards off.

We made a wide swing right, entered the mouth of the draw, and crawled our way to a downed tree. Budz pulled out the fan again and clucked. Finally, he clamped my shoulder. “When I tell you, come up and shoot him. He’s only 20 yards off.”

There was a quaver in his voice. Here was a guy who had killed hundreds of turkeys and put guys like me—O.K., not exactly like me—on hundreds more. And he still trembled when the moment came. I rose up with the gun shouldered and saw the tom heading straight at the fan. I couldn’t shoot at his neck, because his head was forward, right in his center of mass, as he charged. So that’s where I shot—and killed him convincingly.

“That’s what I’m talking about!” Budz exulted, punching me in the shoulder. Then he got quiet. “Now let’s get after the rest,” he whispered, and took off. I almost ran right over my bird. Budz figured the others were just over the next rise, but when he peered out from behind the turkey fan, they were gone.

“That’s all right. You did good back there,” he said. “He was only a jake, but you nailed him.” I was a bit disappointed to have killed a jake, but at least I didn’t miss. As we returned and I picked up the bird, I noted that it felt pretty heavy. It also had a 9-inch beard and spurs that looked to be about an inch long.

“You sure this is a—” I started to ask.

“Hosing you, man! That’s a big tom! I bet he’s 3 years old.” I could see at that moment how much he’d wanted me to succeed. Now that I had, the pressure was off and he could enjoy my success and his. I was so happy that it didn’t bother me that I would never hear the end of how badly I’d screwed up that first day.

Unstoppable

The next three days I spent hunting with Budz, Jenny, and his buddies were a blur. I limited out in Kansas before 8:30 on our first day. Then I tagged two more toms in Nebraska for a total of five, which is three more than I’ve ever taken in a season. But I couldn’t tell you which birds I killed where or even the names of some of the towns we stayed in. And it took me about a week to recover.

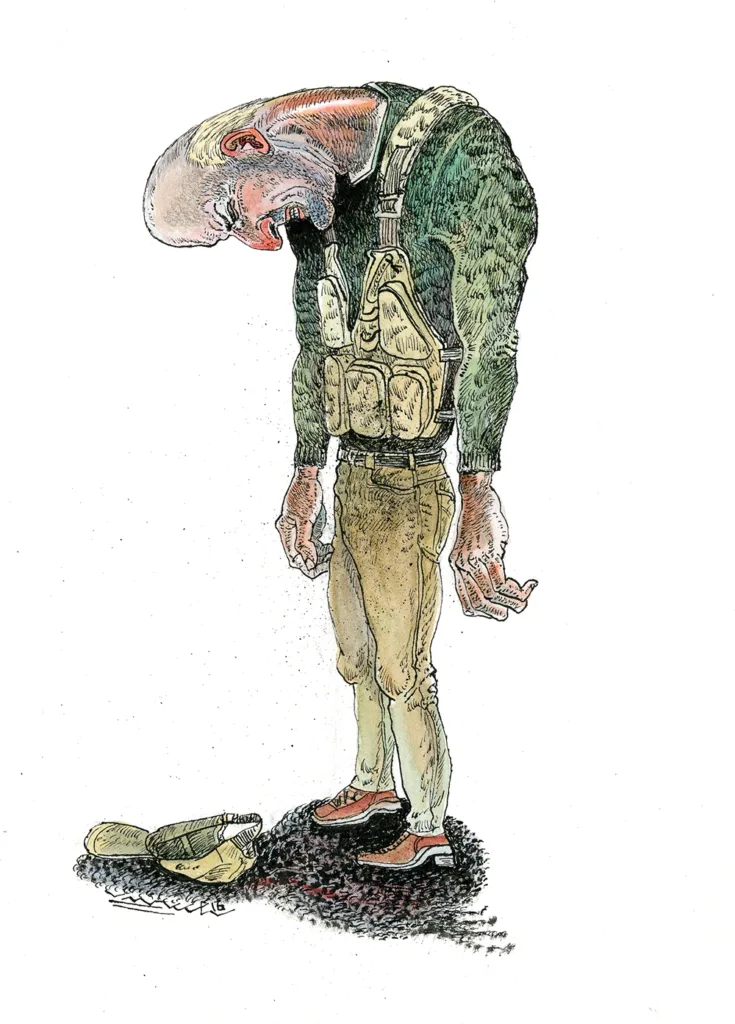

One of the most telling moments came when there wasn’t a turkey in sight. It was midmorning. The road was greasy, so we drove on the grass alongside. We were doing fine until the Expedition came to an abrupt stop. Budz had high-centered the truck on a hump. He, Jenny, and I got out to see the vehicle resting on its belly like a stranded turtle.

Budz tried jacking up all four wheels in turn. Jenny and I gathered stones from the road and carried them in cupped hands; we pulled branches from a dead tree and shoved them beneath the wheels. Nothing helped.

A strange look entered Budz’s eyes, as if he and the vehicle were the only things that existed. One of them needed to yield. And it wasn’t going to be him. “Have to dig her out,” he said flatly. We had nothing with which to dig except the flat end of the tire iron. Didn’t matter. Budz intended to dig out an 18-foot, three-ton SUV, stranded atop heavy clay soil choked with deep-rooted prairie grass, with the equivalent of a large screwdriver.

He wormed his way beneath the front bumper and disappeared. Then he went about digging in a cold, wordless fury. Handfuls of clay and grass flew from beneath the vehicle. It was like a nature video about a bear or wolverine digging its winter lair, where all you see is the dirt coming out of the hole. It was a little scary. He wasn’t digging like somebody who had a stuck car. He was digging like a prisoner who had to tunnel his way out of his cell or be executed in the morning. I wanted to help, but this had clearly become Budz’s fight. He didn’t seem to want or need anyone else’s help. When he finally emerged, his shirt and pants were plastered to his body. It was the first time I’d seen him sweat or breathe hard. Then he got in the vehicle, started it, drove forward, and called, “Let’s go kill some turkeys.”

Later, I asked Jenny where his fury had come from. “Don’t you get it?” she said. “That car was the only thing between him and the turkeys.” I nodded, but it still took me a minute to understand. If I get a car stuck, I size up the situation in terms of what my options and capabilities are. Budz never asks those questions. The car needed to be unstuck so we could hunt turkeys. There was no thought about whether he was capable of getting it unstuck. He doesn’t think that way. His capabilities are whatever is needed to remove the obstacle in his way. No money? Sleep in the truck. No refrigerator? Eat food that doesn’t require it. The bird is strutting atop a mountain, a cliff, or a flagpole? You climb the mountain, cliff, or flagpole. The fate of anything in between him and turkeys has been decided long before the obstacle even presents itself. Obstacles, by Budz’s definition, are just things to be obliterated in order to get where he wants to be.

The Future

Budz was once quoted in this magazine

advising anyone who wanted to follow his example to smash his wedding ring with a hammer. This is interesting, considering that he has brought his girlfriend along on the trip. Could it be that Budz, as he closes in on his 100th slam, is discovering that there’s more to life than turkeys?

On our last night, eating tacos in a brightly lit chain restaurant about to close, I ask Budz what he intends to do once he reaches 100 slams. “I’m going to slow down a bit,” he says, then catches himself. “Wait. I’ll never slow down. Let’s just say it won’t be such a priority.”

With his closest living rival in the 40s, he says he can’t see 100 slams being surpassed in his lifetime. “They’d have to kill me. And even then, it’d still take, what, another 15 years?”

There it is. They’d have to kill him. That’s the only kind of failure he can imagine. But, I persist, surely someone will overtake him eventually. All records, after all, get broken.

“Not mine,” he says. Then his face brightens as he eyes me, Jenny, and Brammer in turn. “We leave at 9 tomorrow morning for the airport. We can sleep for almost four hours and hunt till 8. Who’s in?”

He’s definitely not dead yet.

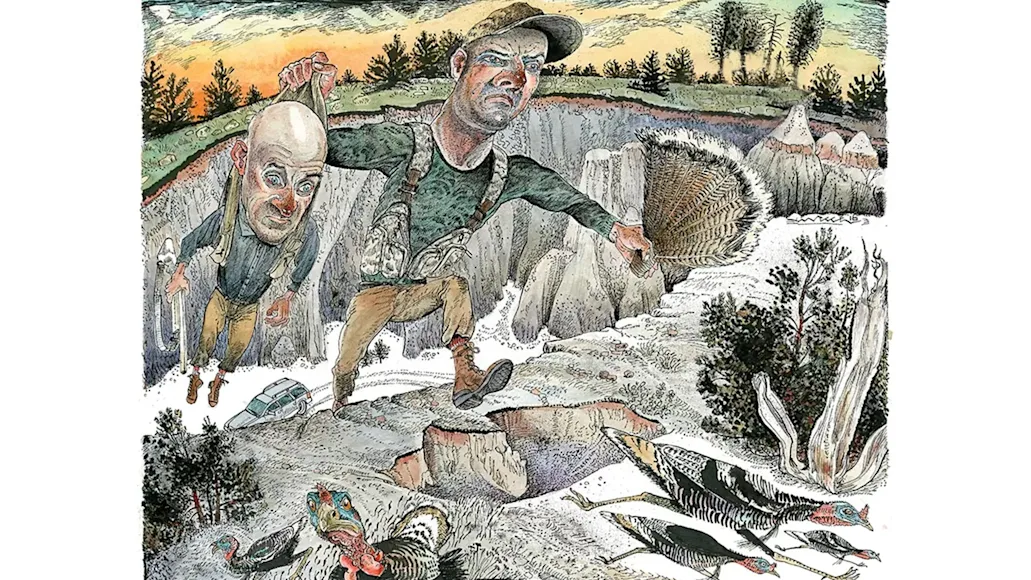

Illustrations by Jack Unruh