Field & Stream has long celebrated the bond between hunters and their dogs. Our photo editor discovered these pictures dating from the ’30s to the early ’70s in our files. They show a very different era of hunting, when whitetails and turkeys were scarce in most places, and hunting, for a lot of people, involved bird dogs, retrievers, or hounds. These pictures show the bond between dogs and hunters, and the qualities that make us love them so much.

Crime-Fighting Hounds

Field & Stream Archives

Some hunting dogs hunt people. This trio is all smiles in the picture, but Kentucky’s Captain Volney (V.G.) Mullikan and his bloodhounds were relentless on the trail. Mullikan caught more than 2,500 escaped criminals throughout the Southeast in the early part of the 20th century. He and his most famous dog, Nick Carter, were big enough stars that crowds gathered to watch them work. Their longest chase was 50 miles after some bank robbers.

The caption doesn’t say if one of the bloodhounds pictured here is Nick Carter, but it shows a pair of dogs bred to be self-propelled noses. They are big and powerful, built to stay on the trail until they reach its end. They have low-set, droopy ears that brush the ground, stirring up scent particles. The jowls, wrinkles, and dewlaps all catch and hold some of those particles, too.

Bloodhounds were originally used to hunt deer and wild boar, and in France they are still called St. Hubert’s hounds, after the patron saint of hunters. But somewhere along the way, somebody figured out they were very good at finding people, too.

Pup Tent

Field & Stream Archives

Who needs a perfect smile when you have a hound puppy tucked in your coat? All we know about this picture is that it is dated 1964, but it could be from any time.

Head of the Class

Field & Stream Archives

All it says on the back of this picture is “Sep 1955,” and there is so much more I want to know. From the odd-shaped dummy in the dog’s mouth to the random bird and mammal tracks (including what appears to be a human footprint) drawn on the chalkboard, I have no idea what they’re teaching in this class. All seem to be enjoying themselves except for the Lab, which has a “get this out of my mouth” look in its eyes.

Ice Breaker

Field & Stream Archives

German shorthaired pointers and Brittanys were bred to be versatile dogs, capable of hunting fur and feathers and retrieving waterfowl. In this 1960 photo, the shorthair seems to have decided that versatility isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. He has wisely decided to watch while Duke the Brit clambers out of the cold water and over the ice to complete this retrieve. Neither dog really belongs on a late-season duck hunt. This is a job for a Lab, or maybe a wire-haired pointing griffon, but these two—well, the Brit anyway—are doing their best to do what they have been asked to do, which is another reason we love dogs.

Hot Dogs

Field & Stream Archives

This pack of hounds is being led into the water by the lead dogs. They are somewhere dry, hot, and western—and probably need to cool down, even though no one’s tongue is hanging out in this picture. Dogs control heat primarily by panting, but they also sweat a little from the bottoms of their feet. Getting their feet wet and letting them flop on their bellies, where hair is sparse, is a good way to keep dogs from overheating. One of the dogs looks like a setter, or maybe a setter-hound mix of some kind.

Hidden Gem

Field & Stream Archives

Two hunters and a Chesapeake Bay retriever lurk behind an uprooted tree, watching over a spread of snow-goose decoys. The Chessie is a good choice for retrieving birds on big water. Chesapeake Bay retrievers have one of the best breed-origin stories. They are descended from a pair of St. John’s water dogs, which were originally fishermen’s dogs that retrieved lines and nets developed in Newfoundland. Visiting English sports saw their potential as waterfowl retrievers and began shipping them home around 1800. Two of those dogs, however, were on a vessel that foundered off the coast of Maryland in 1807. The pair, a male named Sailor and a female later named Canton (after the boat that rescued them), were separated and bred with local dogs, eventually producing the Chesapeake Bay retriever we know today. A favorite of market hunters, Chessies were rugged enough to retrieve big hauls of ducks in harsh conditions and guard their master’s bag until he could get the birds to market.

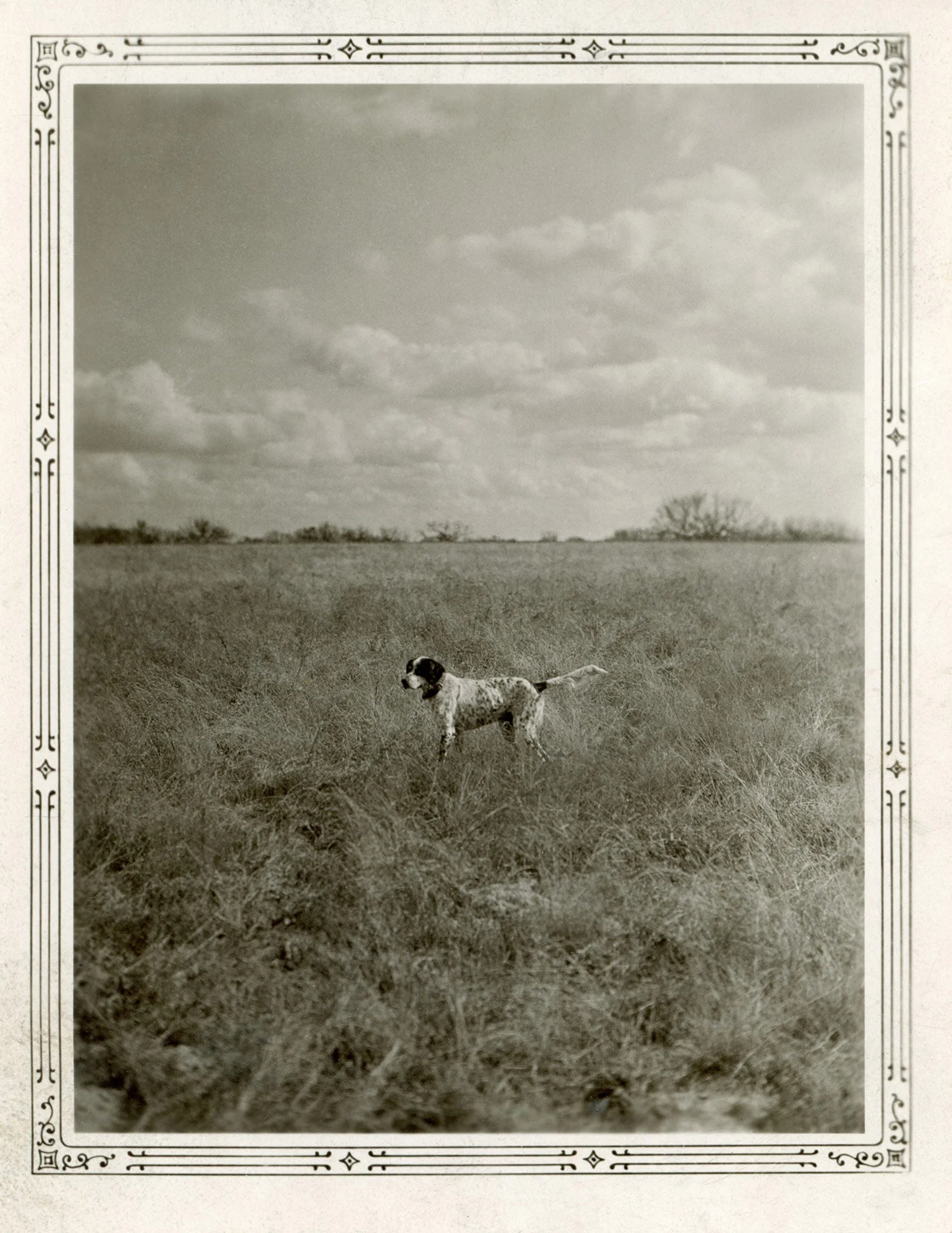

Point Taken

Field & Stream Archives

English setter Smokey strikes a pose on point in this picture from April 1940. Note the tail sticking out parallel to the ground, not up like a whip antenna in the current fashion. There were reasons behind both styles. The high tail makes dogs easier to locate in tall grass, when sometimes that furry flag is all you can see. Go back a few hundred years though, when hunters used pointing dogs to locate birds, then threw nets over them, and you can see how a high tail would get in the way. Personally, I like the old-school straight or even low tail, but there’s no denying it’s easier to find a dog if its tail is up. And even though my dog Zeke has a cropped tail, there have been times the tip of that stub sticking up out of the cover was the only indicator of where he was.

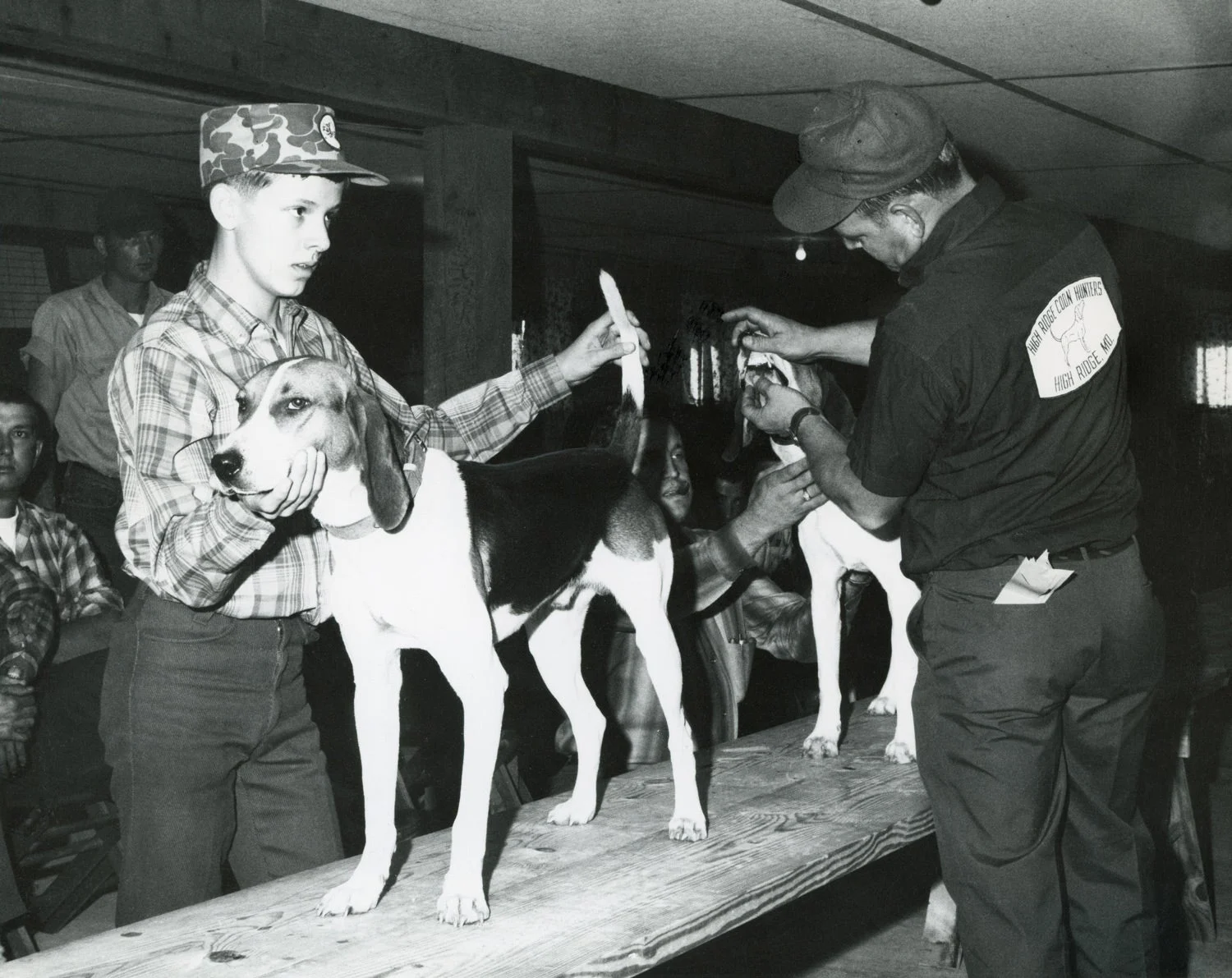

Who Are You Calling ‘Splay-Footed’?

Field & Stream Archives

Dated July 1969, this photo is one of the few with a full caption on the back. It reads, somewhat harshly: “Some houndsmen are deeply concerned with breeding perfectly built dogs. Here a young hunter hopefully shows his hound on the bench. The judge, however, will not fail to notice the hound’s splay-footed stance. If the appearance is important, watch for these points in both the sire and the dam of a prospective litter.” The dog may have splayed feet, but it makes up for it with a 10-out-of-10 side-eye.

Snow Day

Field & Stream Archives

You have to like everything about this 1959 photo. Beagles and snow are a recipe for a great day outdoors. The hunters will able to see the dogs as they chase as well as hear them circle and bring the rabbits by in gun range. It’s going to be glorious, and these guys have dressed for the occasion. Who wears wool that well anymore? The hunter on the right carries a Remington autoloader. It’s hard to tell whether it’s a Model 58 or an 11-48, and it has a PolyChoke on the muzzle, too. It was state of the art for the bygone era this picture captures so well.

Winning Pair

Field & Stream Archives

A boy and his dog is a timeless story, although this one happens to date from 1935. The setter pup has a dove in its mouth, the boy has a shotgun he will have to grow into, and they are going to have some good years together. About six years, to be exact, when the boy may have to take his place among other members of the Greatest Generation and trade that shotgun for a rifle.

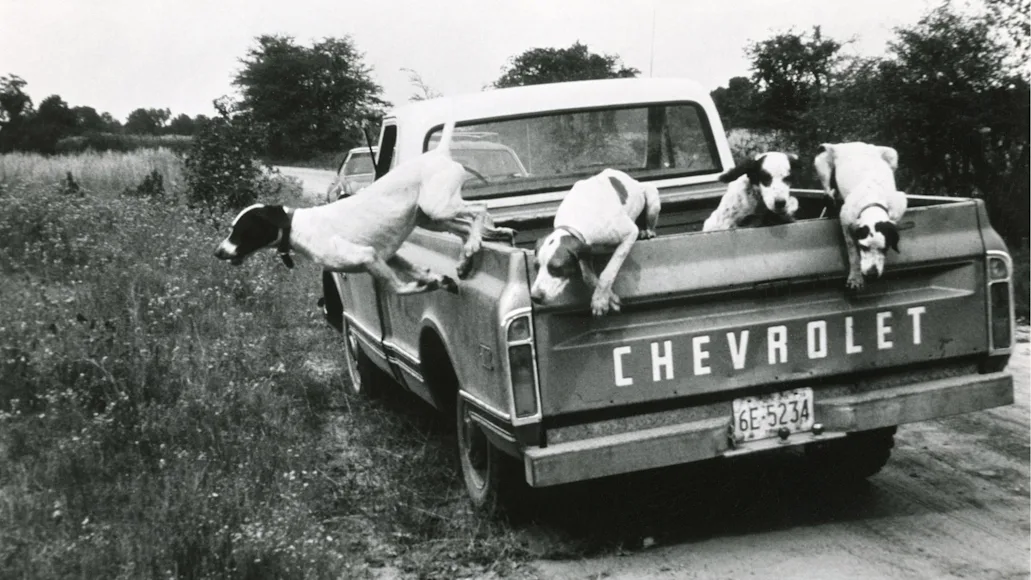

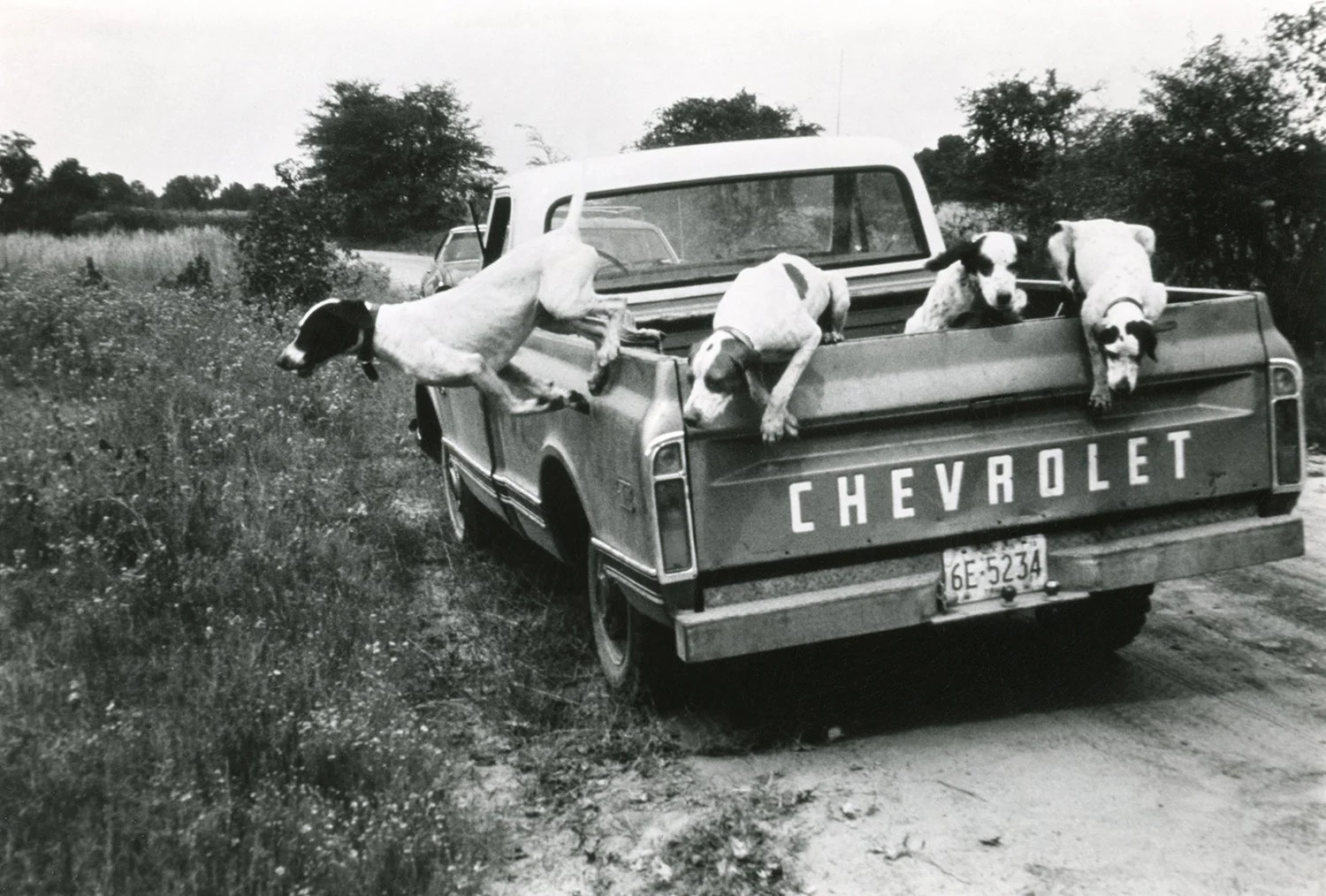

The Joy of Bird Dogs

Field & Stream Archives

Yes, they should be in crates for their safety, but if they were, we wouldn’t have this 1972 image of Texas pointers bailing out of a pickup bed. The picture captures the enthusiasm and prey drive of bird dogs perfectly. One of the dumbest things you’ll hear nonhunters say about us is that we make the dogs go hunting. Make them go hunting? Try to stop them. You can’t, and you shouldn’t. What you should do is be inspired by your dog’s uncomplicated, unbridled joy for the hunt. If you need motivation to go hunting more, get a hunting dog.

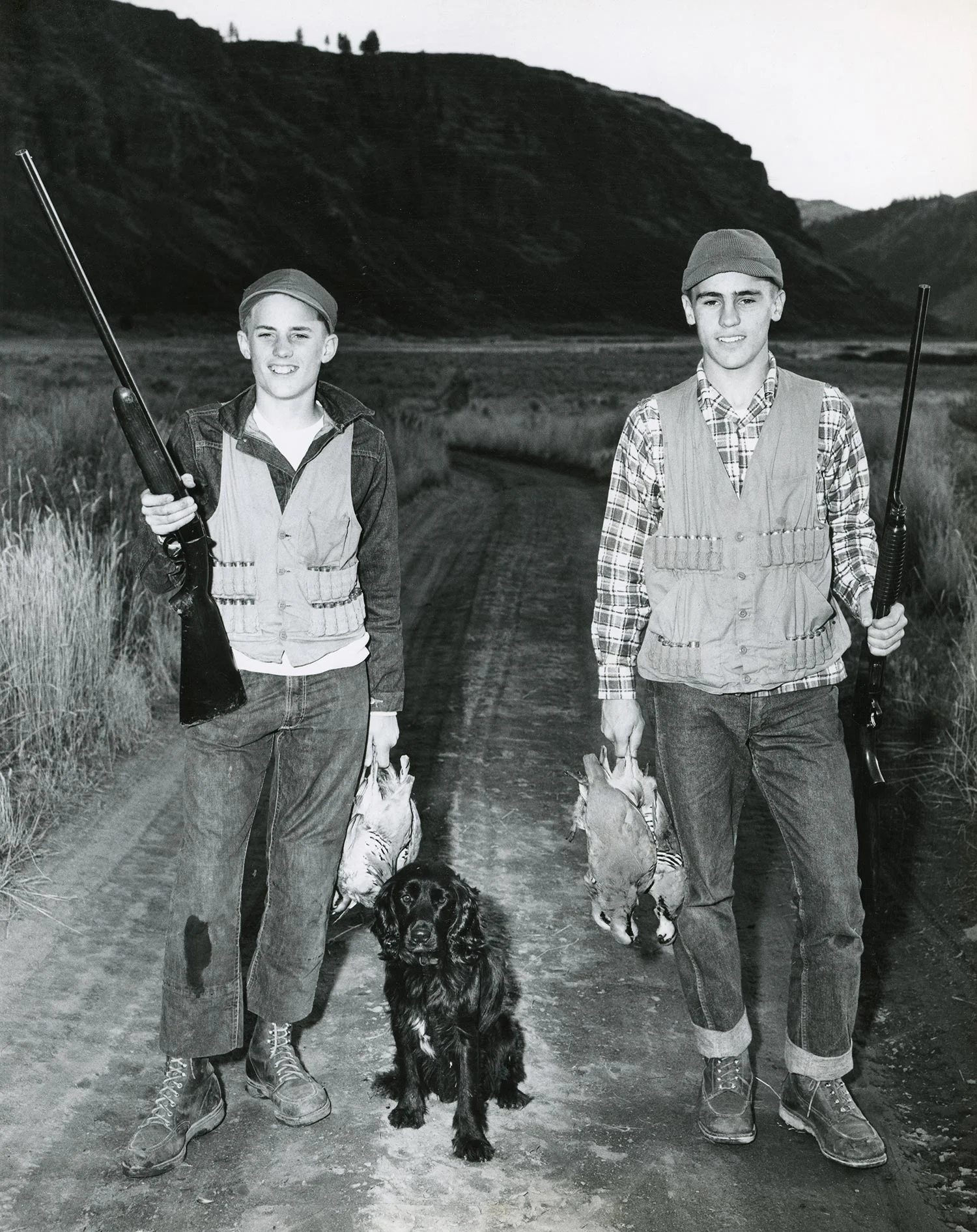

Charcoal, the Chukar Dog

Field & Stream Archives

This photo, from 1963, was taken on the south fork of the Boise River. The caption reads: “Phil and Richie Gerlach with Charcoal, whose legs are too long for the bench but long enough to get birds into air [and] the shot pattern.” Phil, on the left, is 13 years old and has clearly outgrown those jeans, and the Model 37 Winchester single-shot is likely a hand-me-down from 15-year-old Richie, once he graduated to the Ithaca pump (coincidentally also a Model 37). The boys have a fistful of chukars apiece, although the shell loops on their vests are suspiciously full, making me think this photo isn’t 100 percent candid. For his part, Charcoal doesn’t seem to be at all bothered that his legs are too long for a successful career as a show dog. That extra length probably comes in handy for clambering up the slopes of chukar country.

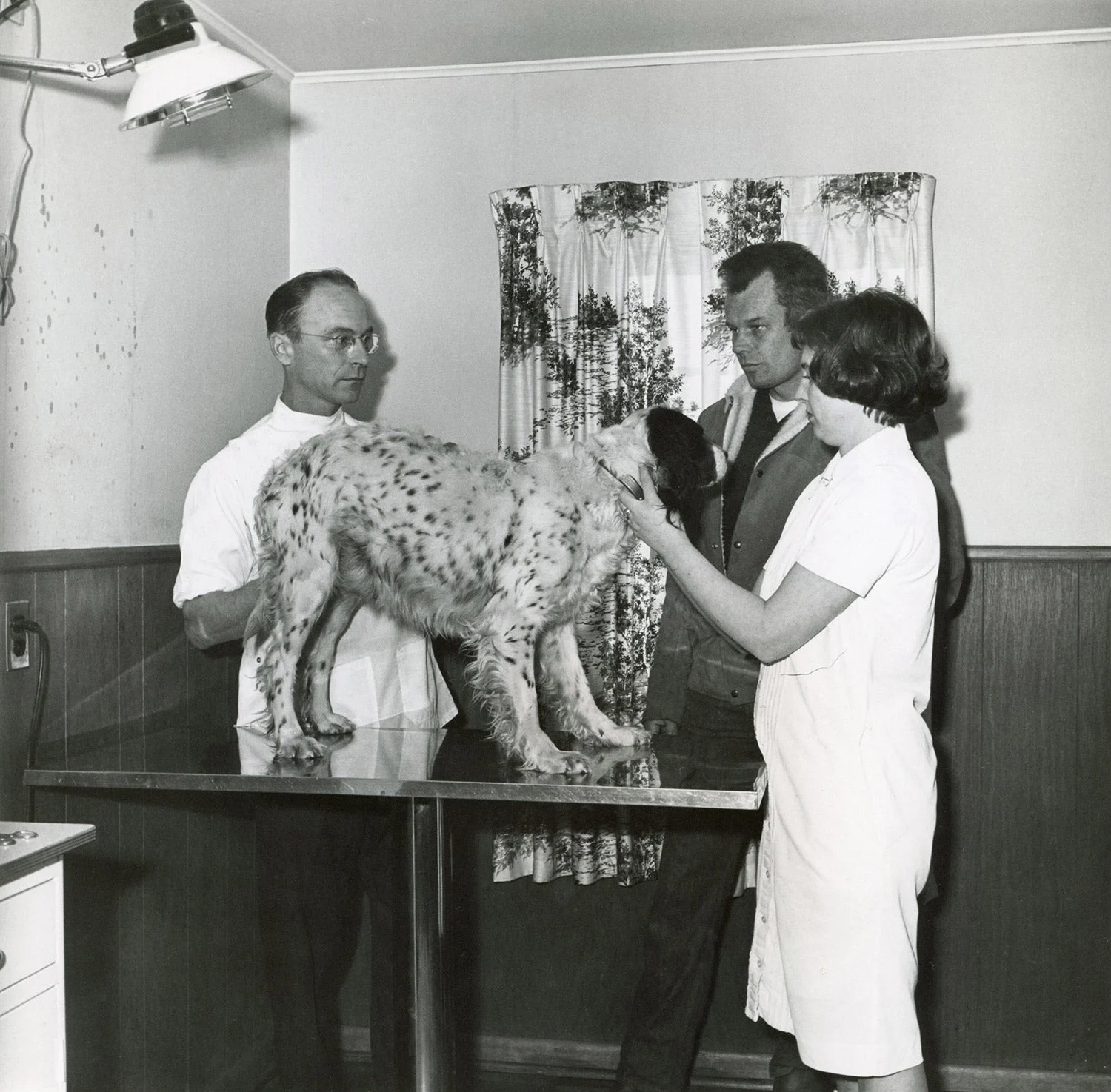

The Price of Love (and Birds)

Field & Stream Archives

This setter looks a bit apprehensive about its vet visit, dated 1967. In my experience with bird dogs, they are good at three things: loving you, finding birds, and costing you money. The cost varies. Aside from normal checkups and shots, my setter, Ike, never cost me a nickel in vet bills in 14 years. My last shorthair, Jed, cost me thousands over a similar timespan. This dog looks healthy and ready to hunt, though when I had a setter, I’d clip his hair short to keep it from gathering burrs in the field, then let him grow all the pretty feathers back in the off-season.

Pop Break

Field & Stream Archives

Dogs have to hydrate, especially in the heat, and if there isn’t water around, you need to carry it with you. Every year, early in the season, hunters lose dogs to dehydration and heatstroke. In 1956, when this picture was taken, pop came only in glass bottles, as plastic bottles weren’t as common as they are now. Hence, this dog is drinking from a glass Pepsi bottle.

The Night Shift

Field & Stream Archives

“Success at last,” reads the caption of this 1949 photo. “Mr. ’Coon is finally dislodged from his branch and the digs (sic) close in to finish him off.” For those who love it, running through the woods and mud in the dark after hounds makes daytime hunting seem tame and boring by comparison.

Picture Perfect

Field & Stream Archives

It gets no more classic than this 1971 picture of a setter, a bag of woodcock, a leather cartridge box, and a pair of classic doubles at George Bird Evans’ Old Hemlock home in West Virginia. An artist, sporting author, and dog man, Evans bred his Old Hemlock line to recover some of the traditional setter looks that he believed had been lost through breeding for field trails. They were tall, with the blocky heads and droopy jowls you see on this dog. As the former owner of an old-school setter myself, I may be biased, but I think there is no better-looking bird dog.

Platinum-Status Pooch

Field & Stream Archives

In 1966, when this picture was taken, you wore a necktie to travel and you could carry a shotgun onto a plane. Dogs couldn’t come in the cabin, but they got the same first-class treatment as travelers, before air travel devolved to the sorry state it’s in today. You can still fly dogs, though, with enough prior planning. Most gun dogs weigh more than the 20-pound limit to carry them aboard, so they will have to fly as checked luggage or, at double or triple the cost, as cargo. There are also private dog-shipping services you can use. Research these carriers: Some are better with dogs than others. Book direct flights, be sure the dog is well-enough crate-trained to be relaxed in the box, and take a trip that broadens both of your horizons.

Lady and the Tramp

Field & Stream Archives

Taken in 1934, this picture shows a springer, a handful of woodcock, and a woman dressed to kill in elegant wool and a classy, side-plated side-by-side. The wooden fence and the second growth suggest the pair is hunting one of the many abandoned farms in the Northeast. In the Colonial era, much of the forest here was cleared and farmed. Beginning around 1850, farm abandonment was common as people gave up country life and moved to growing cities. One result was a bounty of young second growth over a period of almost 100 years that made perfect cover for grouse and woodcock. As those forests matured, woodcock numbers, especially, dwindled, making scenes like this one less frequent than they used to be.

Muddy Buddy

Field & Stream Archives

Photographed in 1964, this spaniel has a woodcock in its mouth, muddy paws, and a look of devotion and almost desperate eagerness to please in its eyes. We have bird dogs, and we love them because they are so eager to do what we ask them to. If they slip in the field, it’s usually our fault as trainers for not making our expectations clear.

The Odd Couple

Field & Stream Archives

These two hunters, photographed in 1960, are having a good day on woodcock over a German shorthair and an English pointer. The hunters themselves are a bit of an odd couple: The guy on the left with a cigar and a pump gun looks like he’s a serious hunter. The hunter on the right is bareheaded, with a single-shot gun and…that shirt, though. But he’s got a bird, he’s having a great day, and the dogs don’t care how much he hunts, what kind of gun he shoots, or what shirt he wears. We should strive to be as nonjudgmental as our dogs are. All the shorthair wants is some attention from his man—especially because he already has an arm around the pointer.

The Legend of Old Hemlock

Field & Stream Archives

Here is George Bird Evans with a pair of Old Hemlock setters and a grouse. He is living the upland shooting life that he wrote about eloquently in the book of the same title. Evans and his wife, Kay, bought the aging West Virginia farmhouse they renovated and named Old Hemlock in 1939, when Evans was 33. With the exception of wartime service as an illustrator of manuals for the Navy, Evans lived, hunted, and raised setters at Old Hemlock until his death at 91. He was a hugely influential author for 20th-century bird hunters, both through his books and his work in Field & Stream. It’s still possible to find setters from Old Hemlock bloodlines, too.