IT WAS THE KIND of day best spent in a tent

. Freezing rain drizzled relentlessly on the drab tans and browns of an Arctic autumn. The clouds and fog made it just as difficult to see our tent 1,000 feet below as it did to see my quarry, a fairly decent full-curl Dall sheep

. Another 100 yards of skinning my cold, wet hands on the cold wet rocks lay between me and easy shooting range.

The ram had practically walked into our laps. My partner, Dave Dunkin, and I had spotted him while cleaning the breakfast dishes in the creek. I covered the last few yards to a point about 90 yards from the unsuspecting animal. As I squeezed the trigger, I thought to myself that this would have been a good situation for a bowhunter. The ram, and my desire to ever shoot another animal with a rifle, died simultaneously. Now, here we were in the middle of a 20-day backpack trip in the Arctic National Wildlife Range

of Alaska. My ram was down and out of the way. For the rest of the hunt, we could concentrate on Dave’s quest for a bow-killed Dall sheep. Five years he had been trying. This year he would succeed.

The August 1979 issue covered sheep and bird hunting, as well as New York muskies—and muskie fishing. Field & Stream

Dave and I both live and work in Fairbanks in the interior of Alaska. When we started hunting sheep together in 1972, Dave was 30, married, and managing the service station he now co-owns. I was 19, single, and just beginning a career in broadcasting. We had hunted the north fork of the Koyukuk near Mt. Doonerak. When we first hunted there, it was a sheep hunter’s paradise. But the two rams we brought out stirred some interest. The resulting pressure had noticeably lessened the quality of the sheep hunting. It was time to explore new horizons.

I consulted the local office of the Department of Fish and Game. The man I talked to made a few suggestions, one of which really perked up my ears. But I was skeptical since I had no idea there were any sheep that far north.

“Oh sure. The Arctic National Wildlife Range is full of sheep. In fact, in the Hulahula drainage alone there are more than 1,200.”

The Hulahula River is one of several in the range that start off at the Continental Divide and flow north to the Arctic Ocean, which is the northern boundary of the refuge. The 8.9-million-acre wildlife range was set up in 1960 to “protect the unique wildlife and recreation value” of the area. Within its boundaries are found a full spectrum of ecosystems from the shores of the Arctic Ocean over the Continental Divide down to the northern fringes of the Yukon Basin. There is also a healthy population of Dall sheep, which happens to be entirely huntable.

The fish and game man couldn’t be too specific; showing hunters where to find the big trophies isn’t the purpose of the Department’s wildlife studies. But he could give me some good general directions to an area he liked. In fact, he was so confident of his advice that he issued a challenge: “If you go where I showed you for a week or more and you don’t get a ram…well, all I can say is, you’re not very good sheep hunters!”

We’re not very good sheep hunters. On that 1976 hunt in the Treels sheep country of the Arctic, Dave and I spent 17 days discovering why this beautiful corner of the world was set aside as a refuge. We saw more sheep, bear, and blue sky than I thought possible on a single trip. We also did not fire a single shot with bow or gun. Nevertheless, we accomplished one thing; we were now familiar with a good location for next year’s hunt.

Getting to the Hulahula River from Fairbanks (or, for that matter, from anywhere else) is expensive, uncertain, and hair-raising. In 1977, there was no direct flight to Kaktovik, Barter Island, our jumping-off place. It was necessary to fly the milk run through Barrow and Deadhorse, changing planes once in order to reach our destination. It even took two planes out of Kaktovik to transport us to the river bank where leg power would take over. I felt as if I had been through a review of aviation history in reverse when it was over, having flown in a 737, a twin Otter turboprop, a Cessna 180, and a Piper Super Cub. It was thrilling but there still remained 10 miles of backpacking before we would start hunting, and within those 10 miles would be the biggest thrill yet!

It was the second day of the pack-in and we were taking a rest stop. Three miles more and we would be at our intended campsite. My sweat-soaked t-shirt was just beginning to feel cold when I heard a thump thump sound. It sounded distant.

“What was that?” I asked Dave. We were both facing downhill.

“I dunno. Might be gunfire.” A few moments later I heard it again.

“Get your rifle, Bill.”

I jerked around to ask him why, thinking sheep. But what I saw straight up the mountainside was a little too big, brown, and hairy to be a sheep. Playfully flipping over boulders, 50 yards away, stood a good-size grizzly. He flipped over another boulder which went thump, thump. But this time I didn’t hear it since my heart was also going thump, thump. I reached for my rifle as Dave pulled out his .357 revolver. At the second of my working the bolt, our visitor switched his attention from the rocks to us. Exactly on cue, Dave and I chorused a yell.

Yaaaah!

The bear stood motionless for a very long moment. He couldn’t smell us but he could sure hear us. Finally, dropping to all fours, the grizzly turned tail and pumped up the mountain. He covered in two minutes what would have taken me two hours. I did manage to shoot a few feet of film before he was out of range. For some reason, however, that piece of film turned out rather fuzzy and jiggly.

Two hours later we were setting up camp.

Sheep Camp

During the first week of our stay, we accomplished a lot. We established a comfortable home, explored some of the areas we had missed the year before, and generally reacquainted ourselves with the rigors of climbing and camp life. This is a very important part of our hunting trips. We always bring along everything necessary to insure a comfortable camp, and we also try to allow plenty of time to enjoy it. Some backpackers believe in roughing it in order to keep their packs light. Sure, these individuals have an easier time of it on the way in, but once they get there, life can be pretty miserable. (Of course, being miserable has its appeal to some.) I’ve known some sheep hunters to go on a 15-day trip with under 45 pounds. On this trip, which lasted 20 days, my pack tipped the scales at just under 80. And that’s a lot of work, but I think it’s worth it.

It was during this break-in period that I managed to get my sheep hunting out of the way, as described earlier. Another day was devoted to taking care of meat and trophy. That done, we were ready for some serious bow-hunting. On the morning of September 3, a day we shall both long remember, we hiked in the crisp fall sunshine toward a valley already familiar to us from last year’s hunt.

The valley we were headed for was actually a number of valleys converging into one. At the head of it rose one of the highest mountains in the entire Brooks Range, which fathered a modest glacier and, in turn, a creek. Like many in Alaska, this creek had no name. So we gave it one: Dunkin Creek. Due to ancient glacial action, Dunkin Valley differed from the other valleys we had looked at. This valley was a rich collection of lush basins and rounded knolls between small outcroppings of rock. It looked sheepy.

The only access to Dunkin Valley lay through a steep gorge. Down the middle of this gorge plunged a torrent of foam between flat slabs of rock. Climbing through this mess proved hazardous so we side-hilled up around to the right. In short order, we were strolling through the park-like terrain of the upper valley, the gorge forgotten. Sheepy though the valley looked, it wasn’t until late in the day that our glassing produced anything other than patches of snow and light-colored rocks. It was after three and the lazy part of the day had turned to feeding time; suddenly the valley was alive with sheep. The most approachable bunch was just below the glacier.

“Looks like about 40 of them,” said Dave, peering through our spotting scope. That was bad news. Generally that many sheep in one group would almost have to be ewes and lambs. And generally, at this time of the year, the rams wouldn’t be caught dead hanging out with ewes and lambs. But six years of sheep hunting has taught me that such generalities don’t always hold true.

“Let me see,” I said, hunkering down behind the eyepiece. After a few minutes of eyestrain I rolled over with a verdict. “I think that bunch down by the creek might have horns.” Dave took another look.

“Maybe. Let’s get closer.”

Moving in for a Closer Look

And so we did, being careful not to get so wrapped up in looking at the sheep at the head of the valley that we might overlook something in the basins we were passing. It didn’t take long to establish that the sheep we thought were rams really were rams. But we still had a long way to go and it as getting late. We were just about to call it a day when Dave dropped to a crouch and motioned for me to do the same.

“There are two of them … right up there.” He pointed up to our left to a basin completely in shadow. Slipping out of my pack and digging for scope and binoculars, I asked the expected question.

“Where?”

Dave didn’t answer right away; he was too busy with his binoculars. So I scrambled over to him and immediately saw the two sheep. Almost as immediately I determined that they were rams. They were so close that I really didn’t need the spotting scope. But I set it up anyway for a closer scrutiny. For just a moment, the upper ram raised his head from his feeding for a few seconds. When he did, I got the first and last good look at his horns that we would get for awhile. That one glimpse, though, was all I needed.

“The upper one is absolutely huge.” I told Dave. “Let’s go get him!”

But it wasn’t quite that simple.

Figuring the main valley as running east to west with the glacier at the west end, the two rams were on the east side of a small offshoot basin. The white-capped mountain at its head fed a small creek that dumped into Dunkin Creek almost at our feet. In order to cross that convergence and have a chance at the two rams, we would have to show ourselves to the forty sheep below the glacier. As we pondered this problem, the rams fed a little higher up the mountainside. Now we couldn’t cross without spooking them either. Not only that, but we couldn’t go back. All we could do now was wait.

Mountainsides never look like what they really are when viewed from across a valley or from below. Feeding uphill, our two rams proved that point by disappearing straight into the side of the mountain! There must be some sort of ravine. Whatever it was, we grabbed the opportunity and made the crossing, looping around so the larger group couldn’t see us. Within moments we were climbing the shale slide with nothing between us and the sheep but the swell of the mountain. An impossible situation was now very probable.

For some reason, however, that ram didn’t spook, although I’m sure he saw me. Cocking his head back slightly, his right eye stared hypnotically into mine for what I am sure was a solid 15 minutes. I never even blinked. My right leg turned blue, my hands froze to the rocks and both eyes shriveled up like prunes, but I never moved a muscle.

With adrenalin flowing, we climbed like grizzlies, not even conscious of our straining lungs and muscles. Reaching a predetermined point we figured to be above the rams, we stopped for a quick rest. We then began to inch our way across the face of the mountain, scanning the horizon. This was nerve-racking since the rams were on the move. Naturally we would have preferred to stalk stationary animals, but the lateness of the day gave us no choice; it would be dark before they bedded down again.

Suddenly Dave froze, crouched, and took a step back. He motioned to a spot ahead and a little below us. At first, I didn’t see anything. Then, I saw a big white worm crawling up the maintain. A moment later there were two big white worms. What I was seeing was a couple of inches of the rams’ backs peeking over the swell of the mountain. They were 80 yards away, heads down, moving up and slightly away. Dave and I crawled over to each other. There wasn’t much to say.

“I’ll stay here.” I whispered. “Go ahead, you can do it.”

As I wedged myself between two boulders out of sight of the whole show, Dave crawled ever so slowly forward through lichen-covered rocks. There was no cover anywhere. If it were not for the fact that the two rams were in a slight depression, we would not have a chance. Even so, it was very tight. Fifteen to 20 minutes went by during which Dave progressed about 25 yards. I found that out by taking a quick peek, but that wasn’t enough. Then impatience got the best of me. I decided to get a better look.

The Shot

Moving as slowly as I knew how, I rose from a sitting position to a half-crouch, scanning the mountainside as I did. I couldn’t see a thing. Where are they? I said to myself, They should be right over… Suddenly, I spotted Dave as he flattened and, simultaneously, I saw one of the rams, the smaller one. But it wasn’t a sheep’s back I was looking at; it was a ram’s head! If I was the cause of Dave missing a chance at that big ram, not only would I never forgive myself, but I was sure Dave would shoot me! For some reason, however, that ram didn’t spook, although I’m sure he saw me. He just didn’t identify me as a threat. Cocking his head back slightly, facing uphill to my right, his right eye stared hypnotically into mine for what I am sure was a solid 15 minutes. I never even blinked. My right leg turned blue, my hands froze to the rocks and both eyes shriveled up like prunes, but I never moved a muscle.

Finally, just when I began to think that the motionless sheep head was a rock, it disappeared below the horizon as the ram resumed feeding.

Six o’clock was rapidly approaching, which meant the Arctic sun would soon complete its shallow slide toward the horizon. Dave looked back my way and shook his head. Apparently he couldn’t get any closer. And he wasn’t in position for a decent shot. Again we waited.

Once more fate took a turn in our favor. The rams suddenly tired of available fodder and took a few quick steps deeper into the ravine, presumably toward the second course of the evening meal. Whatever their reasons, it gave Dave the chance he needed. In a matter of seconds, he gained another few yards. Having just noticed that he had forgotten his armguard and shooting glove, Dave now paused to peel off his wool shirt. It would hurt but at least his sleeve wouldn’t deflect the string.

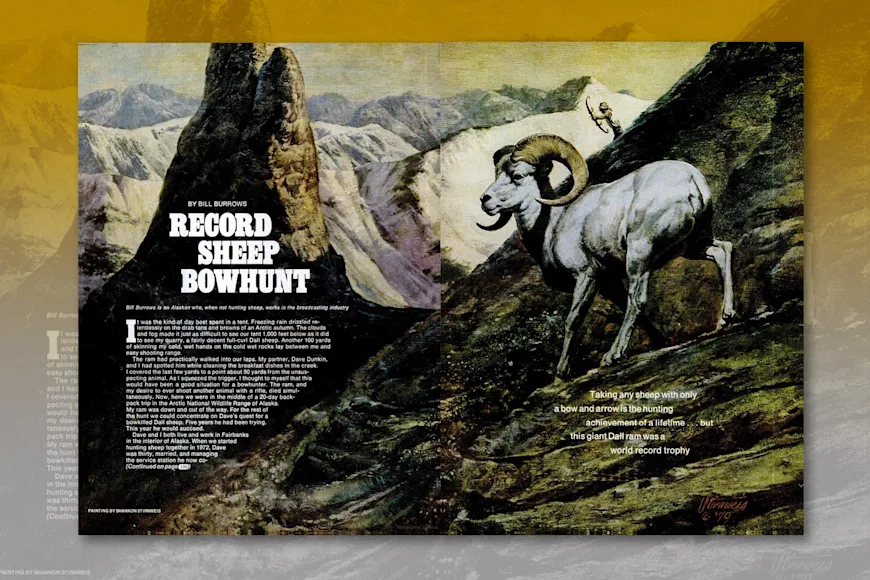

Dave tells me that he never did get a clear view of the big ram’s head. He only knew that the one he would try for was bigger than his companion. From the kneeling position, 40 yards from the upper two-thirds of white body he could see, Dave drew his 65-pound Jennings Compound. He looked as solid as I have ever seen him in front of a target. He held for a few seconds then let fly with perfect form and followthrough. Instantly, I heard a loud chunk. Then, for the first time since we first spotted him, I saw most of the ram’s body as he bucked straight up into the air and dropped from view. My glimpse of the great ram was so momentary that I thought to myself: Did I really see what I thought I saw?

Immediately, four other rams now ran up the far side of the gully not more than 50 yards from Dave, stopped, and looked back. Dave turned to me, still kneeling, and pointed to where the ram had disappeared, shrugging his shoulders as he did. At first I thought he had missed. I called out in a loud whisper.

“Where is he? Did you get him?” I was confused. Was our ram one of the four now nonchalantly feeding beyond the ravine?

“I don’t know.” Dave answered. “I think he’s down there somewhere.”

A New World Record

I looked again at the four rams feeding as if nothing had happened. Suddenly I knew our ram was down; those other four would not still be hanging around if something weren’t wrong. I have seen this sort of behavior before. I scrambled back to our packs for my movie camera. The scene was unchanged when I returned.

Enough time had passed, so we started forward to see what we could see. In only a few yards we spotted the dead ram, not more than 10 feet from where he had been hit. We later found that Dave’s arrow had punctured his heart. I ran ahead and recorded Dave’s approach. As I swung the camera down and zoomed in on the dead ram I let out a gasp.

“My God…”

Lying before us was the most impressive Dall I had ever seen. His body was huge, at least 50 pounds heavier than my ram. And his horns were simply enormous. It was not their length that took my breath away, it was their incredible mass. They were as thick as my arm with the mass carried all the way out. The bulk of the early growth rings swept far below the jawline.

Dave was still staring. I set my camera down and dug out a steel tape. Whipping it around the longer horn I found it to be 41 inches. The other was broomed back pretty badly, but it looked as if it would have been several inches longer in its original state. First measurement of a base was past 13, which, for a Brooks Range ram was impressive.

Thrilled as we were, it was time to cut the back-thumping and get to work. We figured there might be 2 1/2 to 3 hours of usable light left. (Remember, this is the land of the midnight sun.) For some reason, we never even thought about coming back for the meat the next day. Instead, we just cut him up, loaded everything into our packs and took off down the mountain, floating with thoughts of Dave’s accomplishment. It was 8 o’clock and 4 miles to camp.

I have read somewhere that the body has no memory of pain. Maybe this is why our ordeal doesn’t seem so bad …in retrospect. I do remember openly speculating on the possibility of our demise as we waded liquid ice down the middle of that gorge in total darkness. A twisted ankle would have been fatal. As long as I live, packing that sheep down the mountain four miles in the dark will surely stand alone as the stupidest thing I have ever done…right up there with the time we did nearly the same thing in 1972. The important thing is, we made it, pulling into camp sometime after midnight. We stripped off wet clothes in front of the tent and tossed them into the darkness in a kind of euphoric delirium. Hot soup and warm sleeping bags brought us back from the edge.

Dave and I knew we had ourselves some kind of trophy, but we never seriously thought it would do much more than make the Pope and Young record book. Ninety days after it was taken, Dave finally got around to having his ram measured. Pope and Young officials in Anchorage scored the head at 163 2/8, beating the existing World Record by 1/8 of a point! But don’t expect to see Dave’s trophy in any record book. Even though five Pope and Young officials measured the head and even though Pope and Young headquarters has approved that score, Pope and Young has thrown up a final hurdle that a Fairbanks bow hunter who values his trophy would naturally refuse to attempt. Dave has decided not to ship his trophy to Salt Lake City, as required, to be measured again by the competition judges. The risk of loss or damage to a once-in-a-lifetime ram-not to mention the expense—just isn’t worth it. Besides, just having bagged a ram with a bow and arrow, never mind how big it is, is enough of an accomplishment.

_You can find the complete F&S Classics series here

._ Or _read more F&S+

stories._