_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

FFP vs SFP scopes is hot topic these days, with some hunters assuming that the former must be better because it’s what the long-range crowd uses, and because long range is still the trendy thing for now. But deciding what the best scope

is for you—whether you want a first focal plane (FFP) or second focal plane (SFP) scope for your specific type of hunting—isn’t that simple. So let’s break it down.

FFP vs SFP Made Simple

When it comes for FFP vs SFP, the first question to answer is, Do you know and really understand the difference between the two? It’s totally understandable if you don’t. None of articles I’ve read on the topic make the comparison as simple as it should be (over-complicating the uncomplicated seems to be another trend). So, let’s assume your are looking through your scope at a target downrange. From a practical standpoint, FFP vs SFP boils down to this:

FFP Scope: When you adjust the scope’s magnification, the apparent size of the target and the size of the reticle changes.

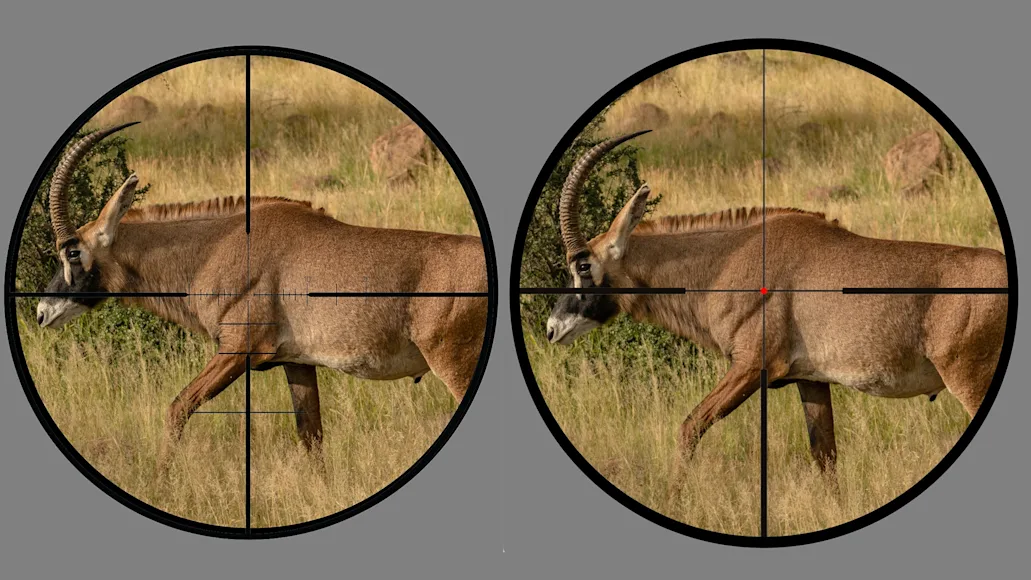

In this example, as you turn up the power on a FFP scope, both the image of the roan and the scope’s reticle get bigger. Richard Mann

SFP Scope: When you adjust the scope’s magnification, only the apparent size of the target changes. The size of the reticle stays the same.

When you turn up the power on a SFP scope, only the image of the roan gets bigger. Not the reticle. Richard Mann

FFP vs SFP: A Demonstration

Another way to look at it is this: A first focal plane riflescope visually fixes the reticle to the target image, while a second focal plane riflescope fixes it to your eyeball. And there’s a simple demonstration you can do right now to understand this better.

Tear a page out of a hunting magazine with a photograph of a deer on it and tape it to the wall. Step back to 10 feet and make a + with your index fingers, and then place that + in front of you eye to line up on the vitals on the deer. Now, while keeping your finger reticle on the deer, walk closer to simulate increasing the magnification like you would with a riflescope. You’ll notice that the deer appears to gets bigger the closer you get, but your fingers stay the same size. That’s what it’s like looking through a SFP riflescope as you adjust the magnification from low to high.

Now, to replicate a FFP riflescope, draw a big + on the deer photo right over the kill zone with a magic marker and walk back 10 feet. Look at the photo with the reticle drawn over it as you walk closer. That’s what it’s like looking through a FFP riflescope as you adjust the magnification from low to high. The deer and the reticle appear larger the closer you get, but their relationship doesn’t change.

In this exmaple, your eye would be on the right and the target downrange to the left. Richard Mann

In the demonstration described above, the position of the “reticle” makes all the difference. The one closer to your eye doesn’t change size and the one closer to the target does. Well, that’s exactly how it works inside a riflescope. With a SFP scope, the reticle is situated behind the magnification assembly—that is, closer to your eye, and its size doesn’t change with magnification adjustments. With a FFP scope, the reticle is placed forward (or on the target side) of the magnification mechanism, and its size does change.

Why Does Focal Plane Matter?

For hunting, a first focal plane scope makes sense if most of your shots are at long range. Richard Mann

When it comes to FFP vs SFP scopes, it matters which one you put on your rifle because each offers certain advantages and disadvantages. So, let’s look at those quickly, then explain them in detail. Here’s the basic lowdown:

FFP Riflescopes

Advantage: Graduated or range-correcting reticles work at any magnification

Disadvantage: At very low power, the reticle can get so small that it’s hard to read

Best For: Long-range precision shooting

SFP Riflescopes

Advantage: Simplicity. The reticle is always the same size and easy to see

Disadvantage: Graduated or range-correcting reticles work only at maximum magnification

Best For: General big-game hunting

If you want to use a graduated—MOA, MIL, or BDC—reticle

to adjust for trajectory or wind, it’s handy to be able to do so regardless of the magnification the riflescope is set at. An FFP riflescope allows this because the relationship between the target image and the reticle never changes. A dot or hash on a FFP riflescope that provides 15 inches of correction at 300 yards when the riflescope is on 6X provides the same 15 inches of correction when the riflescope is on 18X.

A graduated reticle in a SFP riflescope can provide the same correction, but—and this is the critical difference—that correction only equals 15 inches when the SFP riflescope is set to its maximum magnification. This is generally not a terrible thing. If you’re shooting at a distance where trajectory correction is needed, you’ll usually have time to adjust your scope to full magnification if needed. It becomes a problem, however, if you forget to do that, or don’t have time to do it, or when maximum magnification is too much for the shot you’re taking.

Using the highest magnification can become an issue in warm temperatures or when shooting with a hot suppressor because the magnified heat waves can make the target hard to see. It can also be a problem with an unsteady rest because your unsteadiness is magnified, making it seem impossible to hold the rifle still. Of course, you can turn down the magnification, but then the relationship of your SFP reticle and the target changes, making additional aiming points practically useless.

A FFP reticle can be hard to see at very low power, but this isn’t an issue for some shooting, like long-range competition or target work. Richard Mann

The biggest downside to an FFP riflescope is reticle thickness. At maximum magnification FFP riflescope reticles look to be about the perfect size and thickness, but at low magnification—especially if a riflescope has a broad magnification range—the reticle can appear so small and thin, it can become very difficult to see in low light and/or against a dark target. This can make trying to shoot a black bear slipping through the early morning timber difficult.

A thin reticle is typically not an issue for long-range target shooters because they’re usually shooting at targets that stand out in their environment. But because of the interest in long-range hunting, more hunters are turning to FFP riflescopes. What they’re finding is that at low power these reticles become as difficult to see as a thin red hair hiding in your plate of spaghetti and meatballs.

Which is Better for Hunting?

The author prefers a second focal plane scope for virtually all of his big-game hunting. Richard Mann

Neither riflescope is inherently better than the other. It all boils down to how you’ll use it. For the precision long-range shooter, a FFP riflescope is more practical and the best long-range riflescopes are frequently offered only with a reticle situated in the first focal plane. For the common big-game hunter, an SFP riflescope makes more sense, partly because the reticle is always easy to see regardless of the magnification setting, and also because most shots are taken at a distance where significant trajectory correction is not necessary. And, of course, the most reliable way to make a trajectory correction is by clicking it in with the elevation adjustment.

I own some FFP riflescopes and use them on the rifles I often shoot at distance. However, none of my dedicated hunting rifles are outfitted with a FFP riflescope. This is mostly because reticle visibility is more important to me than being able to make reticle corrections. I also don’t intend to shoot much past 300 yards at a big-game animal unless it is wounded, or if I had plenty of time to set up for the shot. On the other hand, when shooting prairie dogs and rock chucks at distance, the FFP riflescope makes a lot of sense.

If you feel the FFP riflescope is a better fit for you—for the shooting you like to do and because of the way you like to hunt—it would probably be a good idea to select one that’s illuminated to help you see it more easily when shooting in dark conditions at hard to see targets at low-magnification settings.