Grizzly bears are the largest predator in North America, but they seldom pose a serious threat to outdoorsmen who’ve taken the proper precautions. According to the National Park Service, historical data shows that on average one person a year dies from a grizzly attack, and since the turn of century, grizzlies and black bears collectively have killed fewer than 50 people in North America. So, though fatal bear run-ins are rare, each year a handful of hunters come face-to-face with these mighty animals and are forced to fight for survival—or simply get lucky and live to tell the tale.

One such hunter was Richard Wesley, who late last month survived a black bear attack while turkey hunting in Ontario. A video of the encounter

, seen nearly 4 million times, serves as a reminder of why bears should not be taken lightly. Here, we’ve collected six similar stories from the F&S archives of hunters who narrowly escaped close calls

with bears, which only further illustrate why these great creatures demand respect. —JR Sullivan, associate editor

A Rude Awakening in Ram Country

“This could’ve ended a lot worse than it did.”

“This could’ve ended a lot worse than it did.” Stephen Vouch

In October 2016, Stephen Vouch, 29, was attacked by a 275-pound black bear while on an Idaho sheep hunt.

I’ve hunted with my friends Bobby and Chris a lot over the years, but this was our first time floating the West Fork of the Salmon River. It was day 14 of our trip, and we hadn’t seen a good-size ram

yet, so we were still pushing it hard. That day, we’d run some big rapids, so we were exhausted by the time we stopped on Sheep Creek.

We set up camp and ate, then I crashed at 10:30. I was sleeping in a bivy sack next to Bobby, with a tarp strung up over us. Well, at 2 a.m., something woke me—it felt as if I were being pulled by the hair. The first thing I did was grab the back of my head, which was all wet, and then I saw this shadowy figure over me. Without realizing it, when the bear had bitten my skull, I’d whacked him in the mouth out of reflex, which made him jump and knock the tarp down on top of us, with my head still right between his front paws.

I yelled and started reaching for my pistol, but the bear had shoved it out of reach while rummaging around. But then Bobby woke up and saw him standing over me and grabbed his Judge revolver. He lifted the tarp to see and then, sticking the gun right above my head, shot the bear in the face from, like, a foot away.

After that, the bear ran up a tree above us, but I managed to find my rifle and put him down quickly. There was blood everywhere. Bobby and Chris helped me clean the wounds and skin the bear. Then we just slept late the next day and kept looking for sheep. It was one of the greatest adventures of my life, and further instilled why you should make sure the guys you’re hunting with know what they’re doing. This could’ve ended a lot worse than it did. —As told to JR Sullivan

Caught Between a Grizzly and Her Cubs

Wunderlich

He thought she was going to kill me.

In the fall of 2010, Kim Wunderlich was bowhunting for elk in Montana’s Gravelly Mountains when a grizzly bear charged.

It was Sept. 17—my 49th birthday. I was bowhunting with my friend John Wasser, and on this day we rode our ATVs about 5 miles from our camp before walking into a drainage.

We could hear bugling on the ridgeline, and by late morning we’d gotten on some bulls, but no shots. It started getting hot, so we decided to hike out. At around 1:30 we were scaling a timbered hillside when we heard a branch break above us. I looked up and there were two grizzly cubs, about 25 yards away, standing on their hind legs. I turned to John and said, “Bear!”

Just then, the sow came at me at full speed. I just remember seeing claws and her mouth. This wasn’t a rear-up attack; it was like getting hit by a car. Right before she barreled into me, I stuck my longbow sideways in her mouth. As we tumbled down the hill, John was screaming, trying to get the bear’s attention. He thought she was going to kill me. This bear probably weighed five, six hundred pounds.

After we came to a stop 15 or 20 yards below, she bit me really high up on the inner thighs. Then she released me.

For a moment I just lay still. I didn’t move until I heard her woofing up the hill a ways. When John got to me, he was shocked to see that I was standing. My arrows were everywhere. I could feel blood running down my legs, but I didn’t want to look at them–fear doesn’t enter in until you know what you’re up against.

It was about a mile and a half to the ATVs, and we had about 1,000 vertical feet to climb. But from that point on my only purpose was to get out of there. We packed the wounds with gauze and went.

By the time we got to the hospital in Dillon it was 8:15 at night. The doctor said the bear missed my femoral artery by 1 centimeter. Officials from Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks took DNA samples from my pants because of another bear attack in the area. So far we haven’t heard the results. —As told to Tom Tiberio

An Empty Rifle and a Charging Bear

“Now we were face-to-face, and my gun was empty.” Rick Hollingsworth

In October 2016, a grizzly bear attacked Rick Hollingsworth, 47, while he was hunting elk in Alberta, Canada.

That morning, my cousin Rob and I were headed out to hunt near the Simonette River, but only I had a rifle with me, since Rob didn’t have a big-game license at the time. We were about half a mile from the truck when we noticed fresh wolf tracks in the snow. As we kept walking, we saw a spot through the woods where crows were scavenging on a dead animal.

I loaded my rifle as we slowly approached, thinking we might come upon a wolf eating the carcass. I heard this low calling sound, but a big spruce was blocking my view, so I couldn’t see what was making it. That’s when Rob yelled, “Grizzly!” The bear charged straight at him, and with no time to lift my gun, I fired from the hip and hit the bear’s shoulder.

As soon as I shot, the grizzly turned and charged at me. I shot again—from maybe 8 yards—but it just kept coming. It swiped at me, spraying its own blood everywhere, but I ducked out of the way. When I shot the third time, the bear was no more than 2 feet away. Now we were face-to-face, and my gun was empty. It swiped at me again, but its arm was hurt. That’s when the bear opened its mouth to bite me—and I shoved my gun’s barrel right down its throat. It chewed on the rifle for a few seconds, but I had stunned it, I think. It backed up 20 yards, giving me a chance to reload and fire a final shot. At last, the bear went off and died in the forest.

The whole event lasted just 10 seconds or so, but it was the most scared I’ve been in my life. I just tried to stay on my feet and remain as big as possible. Grizzlies are beautiful animals, and if there were another way, I would’ve let it live, but it didn’t give me an option. —As told to Charlotte Carroll

RELATED: Mauled: A Fight to the Death with a Black Bear

Wounded Bear Mauls 80-Year-Old

“Next thing I knew I was in a helicopter, with tubes coming out of my arms. Then I fell into blackness.” Bill Husa/Courtesy Chico Enterprise-Record

In 2009, Orval Sanders, 83, was mauled by a black bear that was wounded during a hunt in the Tahoe National Forest.

A group of my friends wanted to get their first bear, so I brought my Plott and Walker hounds to help. When they opened up and started running, I knew they sniffed something big.

We caught up with them 30 minutes later under a pin oak, where they were barking up three bears. My knees give me trouble, and I needed a rest. I knew that you shouldn’t ever get under a treed bear, so I walked to an old deer trail that I thought was a safe distance from the action. Meanwhile, my friend shot and hit one of the bears. After another shot, the bear suddenly jumped from the tree, cleared my friends, and bounded straight for me.

I tried to pull myself up from where I sat, but it was only a moment before he was 6 feet away and rearing up on his hind legs. I threw up my hands to protect my face, and the bear latched onto my arms with his teeth and claws. Then I heard a bang. My friend Charlie had shot the bear in the head.

What happened next is a blur. I remember blood running to the floor of my friend’s truck as he doubled the speed limit to the nearest Forest Service station. Next thing I knew I was in a helicopter, with tubes coming out of my arms. Then I fell into blackness.

I awoke two days later in the Sutter Roseville Medical Center. The doctor told me that if I had arrived one hour later, I would have died. I had lost 4 pints of blood. The bear, which weighed almost 300 pounds, had broken my left arm in four places. Even after therapy, my left thumb is partially paralyzed and a shooting pain comes and goes. It’s a reminder of how powerful these animals are. I was done for the season, but I’m not done forever. I’m just going to watch where I sit.

A Starving Grizzly Charges

“He was coming like a freight train, in total chase-mode.” Greg Brush

On the afternoon of Sunday, August 2, 2009, one old, emaciated brown bear became of great personal concern to Greg Brush. This is his story.

Brush, a veteran salmon fishing guide from the town of Soldotna, was walking his dogs on a rare day off from work. On his hip was a large handgun, a Ruger chambered for the powerful .454 Casull cartridge. Brown bears are a constant presence in Brush’s neighborhood, and many residents feel the largely-unhunted animals have little fear of man.

Because of many bear-related incidents in this area, Brush always has brown bears on his mind, even when walking a well-maintained road. On just such a road, less than 500 yards from his house, Brush stopped when he heard a twig snap behind him. Turning his head toward the sound, Brush saw a monstrous brown bear charging toward him. “There was no warning,” he stresses. “None of the classic teeth-popping or woofing, raising up on hind legs, or bluff-charging that you read about. When I spotted him he was within 15 yards, his head down and his ears pinned back. He was coming like a freight train, in total chase-mode.”

Brush instinctively back-pedaled to avoid the charge, drawing the Ruger from its holster. “I fired from the hip as he closed the distance,” Brush recalls. “I know I missed the first shot, but I clearly hit him after that. I believe I fired four or five shots. “

Brush finally fell on his back on the edge of the road. Miraculously, the bear collapsed a mere five feet from his boot soles, leaving claw marks in the road where Brush had—only seconds before—been standing. The bear was moaning, his huge head still moving, as Brush aimed the Ruger to fire a finishing shot. “By then my gun had jammed,” Greg says. “I frantically called my wife on my cell phone and told her to bring a rifle. When she arrived I finished the bear.”

Greg had to file a Defense of Life or Property (DLP) report after the incident. Biologists determined that the bear, a boar that measured 9′ 6″ from nose to tail (10′ 6″ from paw to paw), was between 15 and 20 years old and weighed between 900 and 1,000 pounds–and was underweight by an estimated 400 pounds. “His teeth were just worn out, and you could see his ribs through his hide,” Brush says. “Normally they are eating mainly salmon, moose calves, or carrion right now as they put on fat for the winter. This bear had grass in his molars, a sure sign he was starving to death. He would not have survived the winter.”

Brush says the boar’s head was huge and heavy. “He had many scars and wounds, indicating he may have been run off by other bears. Two biologists and two veteran bear guides have told me that this was a predatory charge. There was no carcass nearby that he was defending and, obviously, no cubs to protect. Had I not been able to kill him, he’d have killed and likely eaten me.”

In the days following the attack, Brush has spent a lot of time “pondering many what-ifs,” he says. “I’m just so thankful that it wasn’t my wife and/or girls walking down that road [Greg and Sherri have two daughters, Kelsey and Kendra]. And there are so many little things. What if I hadn’t heard that twig? What if I’d missed those shots? I’m not an exceedingly religious man, but someone was watching over me that day. Just getting that heavy Ruger out of the holster and fired in that time frame is nearly impossible. After the incident, I tried to duplicate that shooting, and the most I could pull off was two shots in the seconds it took for the attack to happen.”

Incidents like these prove the difficulty of managing brown bear populations in areas like the Kenai Peninsula. The Alaska Department of Fish & Game says that some critical brown bear habitat is threatened by human encroachment from commercial, recreational and residential developments. Therefore, they severely restrict hunting for browns to help keep populations viable.

But such protection is coming at a cost to the human residents of the Kenai. While incidents as dramatic as Greg Brush’s are rare, human/bear encounters are not. Indeed, 31 DLP shootings were reported in 2008 alone. “There are people who do not take proper care of their garbage and do not respect bears, which I view as a wild and essential symbol of Alaska,” Brush says. “They are part of the reason I moved here many years ago. But there we do take precautions, and do everything we can to give them their space. Unfortunately, bears here have little fear of people. When they smell or see a human, their reaction is rarely one of fear, like you see with bears in more remote areas. Here, many bears encounter people, and instead of fleeing, they associate them with food.—Scott Bestul

Lights, Camera, Grizzly

“When you get a reminder like this that your life depends on your shooting, it kind of motivates you.” Courtesy Gregory Smith/Flickr

Bear guide Charles Allen led Cabela’s Outfitter Journal host James Ladis and cameraman Kerry Seay on a grizzly hunt along Alaska’s Tsiu River, the group was charged by a bear. Allen tells the story:

We had spotted a good boar and were working within range. There were heavy rain and winds of 25 to 30 knots, but Jim made a perfect heart shot with his .375 at 55 yards. The bear went down, got up, Jim shot again, and it went down for good. “There’s two more,” said my assistant guide, James Minifie. And 90 yards away was a very agitated sow and cub. The sow was bouncing up and down. She probably couldn’t make us out as humans through the storm. I gathered everyone up and we began to move away, off the rise we were on. But she spotted us and immediately began charging. You can see me on the film, yelling “Hey bear!” and waving my hands. I was hoping she’d identify me as human, because these are hunted bears and generally very wary. But at that moment, she locked onto my eyes in a way no bear ever had. I knew she was coming, so I shouldered my .404. She was a blur coming up that rise. There was no doubt in my mind that she was going to kill or seriously maim me and then work her way through all four of us. I shot just as she came up on her hind legs to begin her launch into me, and hit just left of dead center. That rolled her over backward, and she came up facing the other way. She was pretty broken up. She only made it 20 yards before she died.

We marked it off, and I shot her at 12 feet. She had a 23-inch skull and was about 9 feet squared. She was 15, which is very old for a bear up here.

That .404 is a pre-1964 Model 70 in .375 that was necked up to a .404. I’m shooting 400-grain Sierra soft points—a lot of recoil. I was going to leave it up here over the winter. But now I’m taking it home to practice. When you get a reminder like this that your life depends on your shooting, it kind of motivates you. —As told to Bill Heavey

Bear Attack Myths Busted (and How to Stay Safe in Bruin Country)

Adaptable, tenacious, and surprisingly fast, bears capture the imagination of outdoorsmen. And bear-attack stories told around campfires for centuries have generated myths and morbid methods of escaping: “I don’t have to outrun the bear, I only have to outrun you.”

In compiling and debunking the following myths I enlisted the help of friends from Montana, Idaho, Wyoming and Alaska, who all have a lot of experience in bear country. Most notably, I interviewed Alaskan guide Phil Shoemaker, who is a living legend among bear hunters.

Following the myth-busting section, you’ll find practical tips and tactics for staying safe in bear country.

Myth 1: Bears Can’t Climb Trees

A black bear climbs down a fallen tree. Windigo Images

Of course bears can climb trees, particularly black bears and young brown bears. Old, heavy-bodied bears have a harder time climbing, but can reach 10 feet or higher to swipe you out of a tree. There aren’t many trees in grizzly habitat, so that subspecies is less likely to climb and it’s possible to save yourself a chewing by squirreling up a tree. But since there are fewer trees to climb, I wouldn’t count on it.

Myth 2: Bears Don’t See Well

Bears can see better than most outdoorsmen think. USFWS

While bears might not have the powerful vision of a pronghorn antelope, they aren’t even close to blind. Shoemaker has been spotted from 300 to 400 yards away, even when he’s hidden and still. He says that a bear’s eyesight is comparable to a human’s vision. So forget the notion that a bear won’t see you trying to slink away.

“They trust their noses most, though,” he stated. “Bears are said to have twice as many scent receptors as bloodhounds, and they’ll almost always circle downwind during an encounter.”

Myth 3: Don’t Look in Their Eyes

A grizzly makes its way toward a party of hikers. NPS

Sometimes staring down an aggressive bear is your best chance to avoid a mauling. Stare the bear in the eyes, and slowly back away. Whatever you do, don’t run. Like cats and dogs, bears like to chase things that run. Fleeing prey triggers the bear’s predatory instinct and will likely spark an attack.

Myth 4: Run Downhill to Escape a Bear

A black bear traverses a mountain side. NPS

Bears traverse their home terrain—uphill and downhill—as easily as a whitetail buck bounds through the hardwoods. Powerful, incredibly coordinated, and capable of flowing like smoke through alder thickets, the bear will always win a sprint. Hollywood movies aside, running never works.

How to Protect Yourself in Bear Country

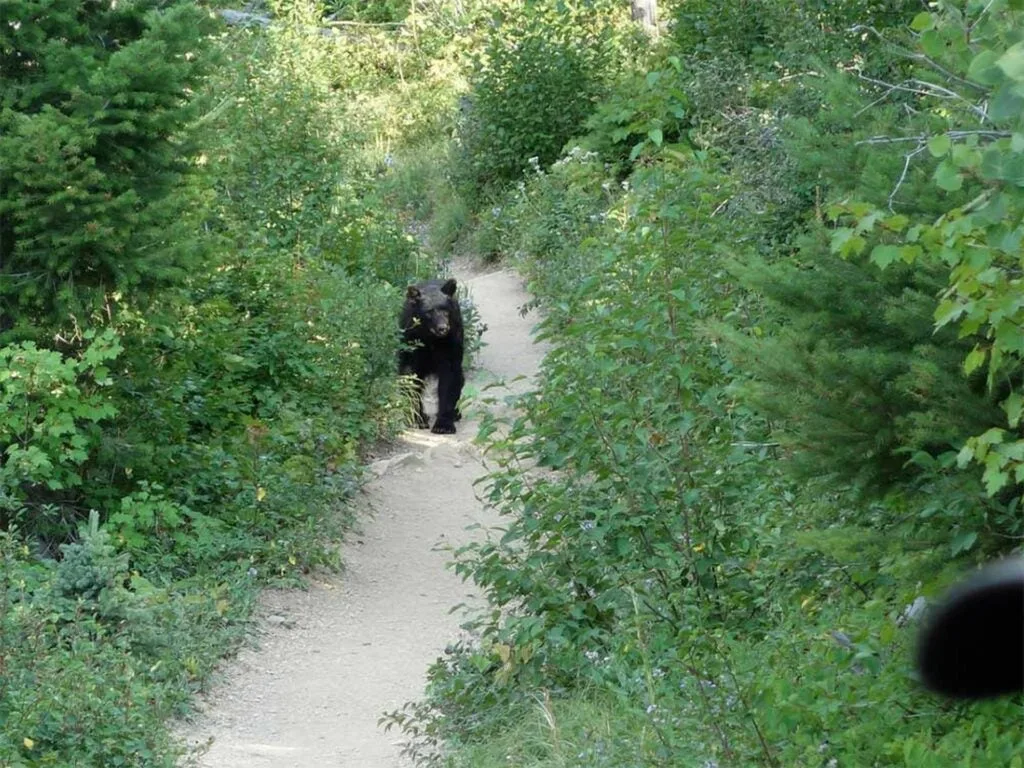

A black bear heading down a hiking trail. Steve via Flickr

1. Read the Bear

When you do encounter a bear, read its body language as if it were a dog. “If you know dogs,” Shoemaker says, “you know more about bears than you think.” Much like a large breed of guard-dog, a bear’s body-language reflects its intentions. A bruin that dashes in with ears erect, eyes bright and focused, is usually just curious.

Pinned ears and an aggressively lowered head indicate territorial behavior. If the bear is stalking you, however, he’s predatory. Determining whether a bear is simply territorial or is predatory will dictate how you deal with the encounter.

2. Electrify your Camp

Protecting your camp with a portable electric fence will make for a restful night in bear country. How does a little electricity flowing through a ribbon deter a half-ton bear? Bears usually bite the fence, which transfers the full voltage and deters the bear from poking around camp.

Compact, lightweight units are available here. The unit will protect a 20- by 20-foot area. Heavier, larger units offer greater coverage—enough to protect a boat, bush plane, or RV. Good bear-avoidance practices such as storing food away from your tent still apply.

Fishermen stand together when a bear approaches. Windigo Images

3. Be a Team

No matter how scary a bear charge might get, you and your companions need to stand as a team. According to Shoemaker, numbers make a difference, whether the bear is predatory or territorial. The larger the group, the more likely the bear is to retreat, even though it might take him a while to do so, Shoemaker says. As a group, slowly back away from a problem bear.

4. Spray and Pray

“I highly recommend bear spray,” Shoemaker says. “It’s non-lethal and particularly good with children around. Lots of folks just aren’t competent with a handgun, and if the deterrent goes wild, others just get spray on them rather than someone getting shot.”

And if a bear wanders too close, you can simply spray him, minimizing legal consequences and paperwork. You don’t even have to believe he’s determined to attack (as you would to use a firearm). Most encounters are with “teenage bears” that are just curious. Pepper spray makes a great educational tool, teaching bears that humans are not to be messed with. Shoemaker has had to kill an unwounded, aggressive bear only once in 40 years.

To use bear spray properly, wait until the bear is fairly close, then spray a “Z” shape into the air in front of him, creating a large cloud of deterrent he’ll run into. Be aware that wind can carry the cloud to the side or even back over you.

For outdoorsmen who are truly competent with handguns, Shoemaker recommends carrying both a sidearm and bear spray.

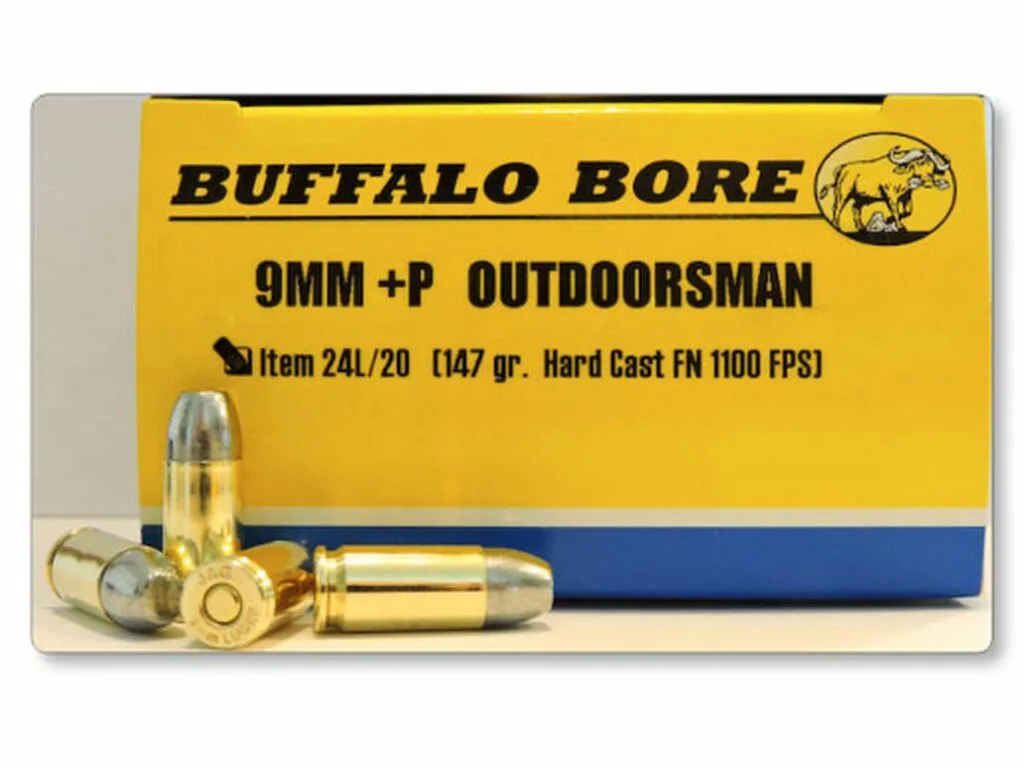

Buffalo Bore ammo. Buffalo Bore

5. Choose the Right Handgun

Conventional wisdom suggests carrying a very powerful revolver such as a .500 S&W Magnum or a .500 Linebaugh. However, a charging grizzly can sprint 50 yards in about 3 seconds. Encounter a charging bear at 25 yards, and you’ve got “One Mississippi-two-Miss…” to draw and fire one perfectly placed shot. Recoil with those powerhouse calibers is so overwhelming that you likely won’t get a follow-up shot. Only a cool head and perfect shooting will save you from a gnawing.

Several Alaskan outdoorsmen are pioneering another approach: Swapping firepower for controllability and quantity. They’re packing 9mms or .357 magnums loaded with deep-penetrating FMJ or hard-cast bullets (such as those made by Buffalo Bore). The thinking is that during a bear charge, they can simply pour it on, rapid-fire, and have a better chance of hitting the bruin’s central nervous system.

Shoemaker points out that while he owns and uses them, extremely powerful handguns tend to be big, heavy, and slow to get into action. As a result they frequently get left behind. Lighter guns are easier to carry.

And Shoemaker knows from first-hand experience. Last year he stopped a full-on close-range charge from a very large brown bear with seven shots from a 9mm.

6. Cook it Well

Did you know that a bear can attack you long after it’s dead? If you don’t cook your bear meat well enough, it could infect you with trichinosis murrelli, a parasite that burrows into your intestines, reproduces, and eventually populates your musculature structure, lymphatic vessels, and bloodstream. Symptoms are nausea, fever, facial edema, hemorrhages in various parts of the eye, heartburn, dyspepsia, and diarrhea. And the parasite is tough to get rid of, taking years in some cases.

But careful cooking is an easy way to avoid the parasite. Trichinosis can’t be killed by freezing, but dies under enough heat. Use a meat thermometer, and cook the bear to an internal temperature of 160 degrees. Here’s how to smoke the bear ham in the photo above.

A bear print in the mud. NPS

7. Keep Calm and Camp On

Bear behavior experts have come to believe that the common human response to a bear tearing a hole in the side of a tent triggers a predatory reaction. Think about it: A bear follows his nose to the succulent smell of camp food, is lead to a tent, and tentatively paws the fabric. Claws tear through, people inside wriggle and scream like rodents in a nest, and the bruin’s neurons suddenly fire: “prey!”

How can you avoid triggering such a reaction? Keep bear spray and a headlamp within reach. And if a bear does try to tear into your tent, stay as calm as possible and fire the spray only if you have to. ––Joseph von Benedikt