The Atacama Desert in northern Chile is one of the driest places in the world other than the poles. It’s about the size of Cuba

, but sometimes receives just a millimeter of rain per year, making it about 50 times more arid than California’s infamous Death Valley. Some parts of the Atacama haven’t seen any precipitation at all in almost half a millennium. Its center—at least as far as scientists know—has never seen a single drop, which leads us to perhaps an unfamiliar question: What is a rain shadow?

This unique ecosystem sits just east of the Pacific Ocean, which cools the air and makes it less able to hold moisture. It’s also in a high-pressure area, which prevents storms from rolling in. But being on the leeward side of the Andes mountains also has something to do with the fact that it’s so hostile to flora and fauna. The longest continental mountain range in the world creates what’s known as a rain shadow, or an area sheltered by the winds necessary to create clouds—and rain. Read on to learn the scientific processes

that cause a rain shadow, where else they are located, and how life manages to find a way in such unforgiving conditions.

Table of Contents

What Causes a Rain Shadow?

How Does Life Exist in a Rain Shadow?

Where Else Are There Rain Shadows?

What Causes a Rain Shadow?

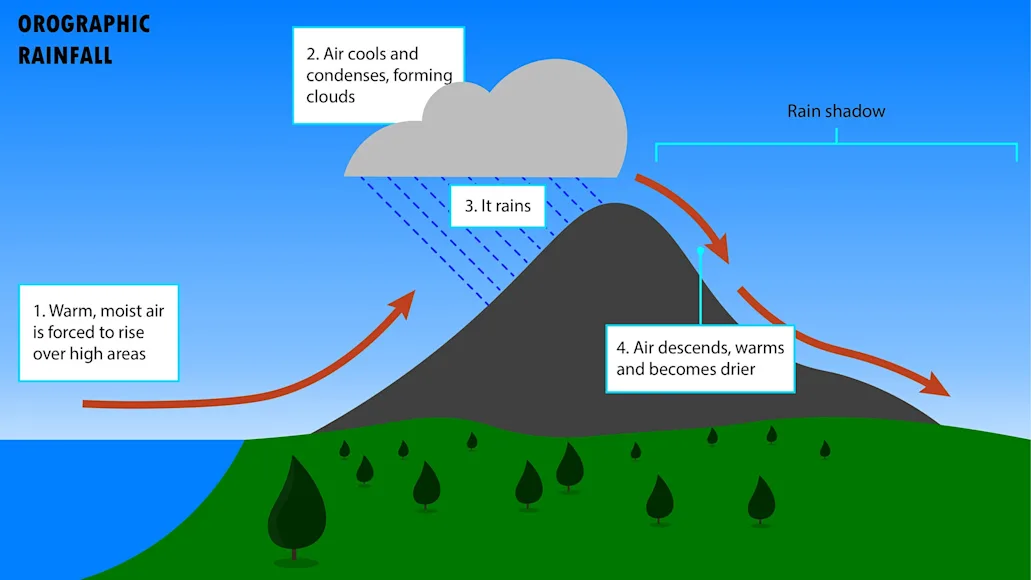

So, what exactly is a rain shadow, and what causes one to occur? Imagine wind traveling from west to east, picking up evaporating moisture as it crosses over the ocean. When that air mass collides with something tall—like a mountain—it has nowhere to go but up. In slightly more scientific terms, it undergoes what’s known as an “orographic lift.”

As air climbs in the atmosphere, there is less air pressure above it. That allows it to expand in an attempt to match the local pressure. And as that air continues to rise and expand, the water within it eventually cools to its dew point, which creates clouds. Sometimes humidity will reach 100 percent, which obviously means rain.

Orographic lift is the reason that mountain crests are some of the wettest places in the world. As well as the reason that their summits are often encircled with mist. Air that’s being orographically lifted up the side of a mountain will continue to expand and cool by a rate of 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit per 1,000 feet as it ascends. This process is known as adiabatic cooling.

By the time the air mass heads down the other side of the mountain, the moisture has been wrung out of it. And the air mass is also heating up as it descends. That is the perfect recipe for truly arid conditions—one that creates the phenomenon known as a rain shadow.

Where Else Are There Rain Shadows?

Next to any mountain range, really. Take the Himalayas, for example, which are adjacent to the Tibetan Plateau—the world’s largest plateau above sea level, and the highest on Earth. For those reasons, it’s often referred to as “the roof of the world.”

Meanwhile, Death Valley might be the most famous example in the U.S. Technically, this very hot and dry desert is a rain shadow of both the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Pacific Coast Range. This particular set of circumstances means it’s one of the most brutal places in the world. The Great Basin, which is an area that constitutes almost all of Nevada as well as half of Utah, and parts of California, Idaho, Oregon, and Wyoming, is also rain-shadowed. It’s bounded by the Sierra Nevada and Wasatch mountains, as well as the Cascade Ranges.

Rain shadows exist on every continent, including Antarctica, which is made of two ice sheets. However, the Transantarctic Mountains that run between them create a rain shadow, which in turn creates three large dry valleys that are not covered in ice.

How Does Life Exist in a Rain Shadow?

The area affected by a rain shadow gets very little precipitation, which means plants can’t really grow there. They’re almost entirely absent from the interior, which means that animal life mostly clings to the shoreline.

The Atacama Desert is similar to Mars than it is to any place on Earth—NASA even studies it. But life still finds a way. The northern portion of the desert is home to specially adapted species like Darwin’s field mouse. Meanwhile, llama, deer, and foxes all scrounge for limited resources in the less-arid southern portion. Avian life includes hummingbirds, swallows, and flamingos. The long-necked, pink birds are specifically adapted to be able to drink the water that does exist there, which has about as much salinity as the water in the Dead Sea.

It’s hard to believe, but more than a million people make their home there as well.