A wan moon hung low over the ridge where we shivered in the silvery darkness before dawn, listening to the sounds of elk

. They were below us, in a timber-rimmed basin with the acoustics of an auditorium, close enough that I could almost feel the vibrations when the nearest bull bellowed.

“That’s him,” hissed guide Sonny Johnson, “deepest elk voice I ever heard. The minute it’s light enough to shoot, take him.”

A high-pitched young bull squealed in adolescent yearning for the cows, and the old bull grunted back. I have heard a lot of bugling elk, but the eerie sound, a sort of melodious, whistling scream that drops suddenly to end in deep guttural grunts, still sends shivers up my spine. I could envision how the old one looked, standing down there somewhere at the edge of the dark timber, throwing his head to issue his breath-frosted challenge.

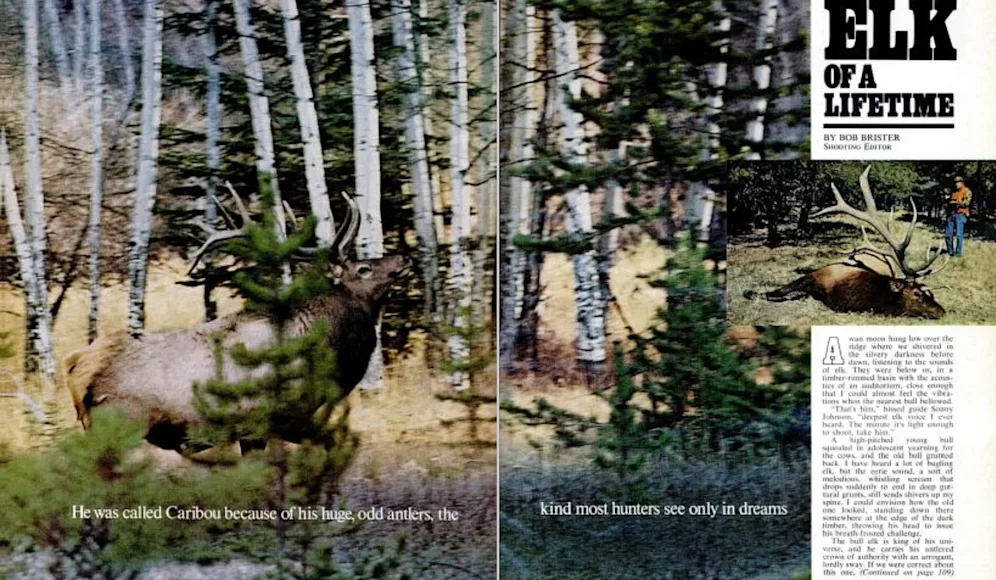

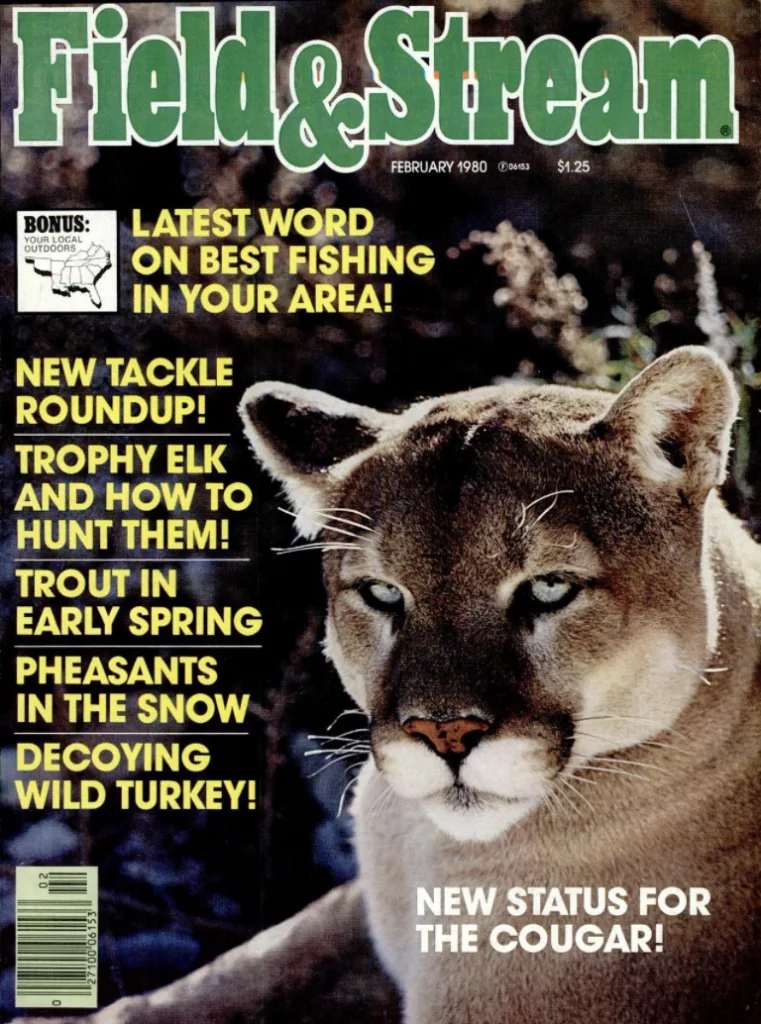

“Elk of a Lifetime” was published in February 1980. Field & Stream

The bull elk is king of his universe, and he carries his antlered crown of authority with an arrogant, lordly sway. If we were correct about this one, that “crown” would be nearly 100 pounds of heavy-beamed “royal” rack, seven points to the side.

A cow let out a yipping bark, and we heard heavy hooves pounding. Then we heard the startling crash of heavy antlers, like the flat side of an ax striking a tree, and there was great pounding of hooves and grunting. The bulls were fighting. I could feel Sonny’s hand trembling when he grabbed my arm. “Can you make ’em out through the scope?” he whispered. “When this scrap is over they’ll probably split and run.”

Through the brilliant 10×40 binoculars I could make out dark heavy bodies, but no more. The scope revealed only an indistinct blur of movement in the shadows of the timber. In the open meadow the cows were starting to move, appearing almost purple in the early light against the frosted grass as they moved into the blackness of the timber.

Then, as if it all had been a dream, the meadow was empty. Sonny stood up and threw his hat on the ground in frustration. “That was him, all right,” he groaned. “Ol’ Crip. He just won’t let himself get caught in the open in daylight. He’s smart even when he’s fightin’.”

For two years Sonny had hunted that seven-point “royal” with the slightly mincing gait that gave him his name. I’d seen the bull the year before, and came to the ranch three days before the opening of the first trophy season in September to scout for him. We’d finally found him in this canyon, and at dusk had watched through binoculars as he bluffed and postured between his harem of some twenty cows and a couple of younger bulls. The sounds of their bugling had been in my head all night, and in the freezing dawn they had been for real.

“We have two options, and three days to hunt,” Sonny said, picking up his battered black Stetson. “We can work our way around the mountain and hope ol’ Crip crosses that opening on the far side; it’s the only opening over there and he has to cross it to get to that black timber where I believe they hole up during the daytime. Or we can try to get up into that ol’ Caribou bull’s territory before he quits bellerin’ this morning.”

“Caribou” was also a bull with a big reputation. His territory was some 25 miles to the north, on the Colorado-New Mexico line, and cowboys on the Vermejo Ranch had named him that because his huge, heavy-beamed rack with two downturned brown tines gave him an almost caribou-like profile at a distance which is about the only way anyone had ever seen him. Every year when the guns started booming the old bull was said to gather his harem and cross the state line into Colorado, seeming to know the season wasn’t open over there, or at least that he would not be hunted there.

“The Caribou may be in Colorado by now,” I decided, “we’re a lot closer to Crip.”

So we climbed up to the old logging road where Louis Kestenbaum waited in his 4-wheel-drive. Louis is recreational director of the huge Vermejo Ranch in the northeastern corner of New Mexico near Raton, a 480,000-acre spread larger than the state of Rhode Island that offers excellent fishing, hunting, backpacking, and even photographic safaris. Game and fish are managed by biologists, and cattle herds have been reduced to provide adequate grass for the elk herds. The early trophy hunts there in September may be the surest bet remaining in America for taking a six-point trophy bull.

Because a back injury prohibited me from riding a horse, Louis had agreed to drive Sonny and me around. We would hunt mostly on foot, and by driving around ahead of us, using the ranch’s many old logging roads, Louis could prevent the wasted time and effort of doubling back to the vehicle.

Although big elk are normally considered creatures of the craggiest high country, this is not necessarily true on the Vermejo, where a herd estimated (by the state) at 4,000 elk roam the mountains and meadows. Some of the largest bulls every year are killed in canyon country on the lower end of the ranch which looks more like mule deer habitat.

“I know that meadow you’re talking about,” Louis was saying to Sonny, “but we’ve got to hurry. I’ll let you guys out at that next ridge, and drive on up the side of the mountain so I can see what’s happening.”

It had sounded easy, but we were puffing and wheezing halfway up the ridge when Sonny suddenly began scrambling and clawing at rocks and oak brush to make the last few yards to the knife-edged ridge overlooking the meadow. He’d obviously heard elk, and for a man who’d undergone open heart surgery a few years before, he was putting on an almost unbelievable show of physical conditioning.

“Run, man, run,” he wheezed, “they’re close.”

Breath coming in sobs, we lay down behind a pile of rocks on the ridge and a second later the first cow stepped out of the timber, looking back over her shoulder. She was about 300 yards away, and I eased down my hat for a rifle rest and wormed into a steady prone position, watching the scope bob up and down with each breath.

Through the crosshairs stepped five more cows, and the scope began to settle. The bull, as usual, came last. And when he stepped out into the sunlit meadow, I almost touched the trigger. His horns were high and heavy, and at a glance I could see seven points. Then he turned his head and Sonny groaned. The right antler was broken off halfway down. For all I know it had been broken in that fight we’d heard before daylight. It was not “Crip;” this bull had absolutely no limp to his gait as he nudged and pushed his cows relentlessly across the opening, refusing to let them stop and feed. He seemed extremely nervous, and at first I thought he’d winded us.

Suddenly Sonny punched me, seeing what the broken-horned bull had seen long before; a beautiful bull with six points to the side was standing on the side of the slope in the timber, watching the cows. He was not Crip either, but he was a very heavy-beamed trophy. “I’d take him,” whispered Sonny, “you may not see another one that good.”

The crosshairs settled on his chest but I couldn’t make up my mind to squeeze. It was only the first morning of a three-day hunt, and Crip and Caribou were both record book candidates, if only I could find one of them. The bull made up my mind for me by disappearing into the timber in the direction of the cows. Sometime later that morning I expect a herd of fine looking females changed ownership; there was no way a bull with one horn could fend off that fine six-pointer.

“You may regret passing him up,” Sonny said, words which were to pass through my mind more than once in the next two days.

We saw elk, lots of elk, and I passed up two more six-pointers. But I’d made up my mind that if I couldn’t take a trophy better than the massive six-pointer I’d killed on this same ranch a few years before, I just wouldn’t shoot.

At dusk that afternoon we set a trap for Crip. We’d carefully scouted the basin where his herd had fed the night before, saw the tracks they’d made coming and going, and set up our ambush on a little knoll overlooking their trail. We figured that they would stay in the heavy timber until dark before venturing out into the open meadow.

At dusk we heard them coming. Two cows passed so close we could have hit them with a rock. Then one came too close, got downwind of us, and let out a warning bark that Crip must have heard loud and clear. We never saw him.

That night in the plush bar and dining room at headquarters, Sonny came back from a meeting of the guides with mixed emotions. “We drew a darned good elk area to hunt tomorrow,” he said, “but it’s nowhere near either Crip or the Caribou’s territory. I figured I knew what you’d want to do, so I swapped our area to another guide for the Torres Vega area up on the Colorado line. Not many elk up there, but it’s where the Caribou lives.”

Next morning we stopped the vehicle before dawn to bugle and listen for an answer. There was none. Four more times we stopped, and might as well have been blowing harmonicas as elk bugles. On the fifth stop the sun was topping the trees overlooking a frost-glittering little meadow in the jack pines, and when I produced the high-pitched whistle of a young bull, there was an immediate deep and guttural answer from about a quarter mile away.

Crunching over the frozen grass, we made as much time as we could, then dropped off into a little gully leading down into a canyon. When the cover played out, we hunched over, and finally began crawling on hands and knees. We could hear the elk clearly, and one was indeed a very deep-throated bull.

Suddenly my heart jumped into my throat. Standing in the sunlight, looking straight at us, was a bull elk. Sonny hadn’t seen him because of a tree in his line of vision. Inch by inch, I eased down flat on the ground and with one eye over the rim of the gully saw the young bull throw back his head and bugle. The big one answered immediately from farther in the timber. Whatever the young bull thought we were, he had more interesting things on his mind.

We worked our way on hands and knees until we could see the tan legs of elk in a little open meadow in the pines. A few yards closer and we could make out the heads of several cows; if we could see them, they could see us. We were afraid to move anymore.

The challenging bull stepped out into an opening. It was a nice sixpointer, so we knew the herd bull was bigger. I picked out the heavy body of the herd bull but could not see his head. His body looked nearly twice the size of the cows. Pulse pounding, I went through the mental checklist: rifle ready, scope clear, yardage less than 200 for a dead-on hold. The ivory tips of antlers moved above the jackpines, looking heavy as tree trunks, and I could have taken him then. But what if he was like that other bull with only one horn? I wanted to see the whole rack first.

The cows were feeding fast, working farther back into the timber, and I knew the bull would come behind them. But three cows we had not seen were moving behind us in the timber, and they must have smelled us. One haughty old girl raised her head high, scanning the air for scent, walking stiff-legged in tight circles. Frantically I tried to make out the bull. He was still behind brush. The cow stopped, looked straight at us, and let out the high-pitched bark that means “adios.”

The whole herd thundered out of there, crashing brush and crunching frozen ground, and we jumped up running, trying to get into position for a snap shot. I had just a glimpse of huge antlers, and he was gone. Back at the vehicle nobody said much. We’d blown it. If the Caribou was as smart as everybody said he was, he would be well on his way into Colorado. We were not far from the line.

“Would it make any sense,” I suggested, “to work our way over to the state line and hunt back from there, just in case we might come across him trying to get up that big canyon into Colorado?”

“Make as much sense as anything we’ve done so far,” Sonny said.

So we rode logging roads through magnificent scenery, alders of yellow and gold and oak brush flaming red, but no elk. By 10 A.M. the temperature had climbed and dust plumed up behind the tires.

“They probably won’t move any more this morning,” Sonny said finally, “but we might come across ’em bedded down in these open jackpines where they can get a little breeze.”

“Only chance he’d get would be a glimpse and a running shot,” Louis said. “Not much chance in this stuff.”

The words were barely out when I saw a cow stand up. Then another. A whole herd was up and running about 150 yards ahead of us, tan shapes through the trees. I jumped out and ran, trying to find an opening big enough to shoot through. At the edge of a little ravine I could see a pathway through the pines about a foot wide. A cow zipped through it, then another, then a spike bull. Then two more cows. Still more cows passed like tan blurs, and the pressure mounted. This had to be the Caribou; only a monster bull could command such a harem.

Then I saw him and it was like a giant tree moving through the jackpines, white tips of antlers shining in the sun, more points than I’d ever seen on an elk. He was running to the right, inches behind a cow, and I led him a little, swung with him, and in the instant of touching the trigger saw a tree trunk in the scope. The elk shifted into high gear, zipping through the trees. There was one more opening, maybe a foot wide. I held the scope on it and waited. When I saw horns I shot, and a great cloud of dust rose above the trees. All I could see were horns.

“Shoot again!” Sonny yelled.

“No need,” said Louis, looking through binoculars. He’s just skidding down that draw, dead as a hammer. Hot dog, what an elk!”

He was indeed the Caribou!

The massive left antler emerged from his skull just above the left eye and was offset to the other so that from the side, we’d been looking at both antlers, one poking slightly out in front of the other. The brow tines on the left were turned down. No wonder I’d seen what looked like a thicket of points. The immensity of him, body as well as antlers, was awesome. And, as always, there was that rare mixture only a hunter knows: elation tempered with respect for a magnificent animal.

The right antler had six points and was perfect; the left contained seven points; one more was broken from fighting. There was a bulbous enlargement of the left main beam perhaps from some early injury. Both antlers measured well over 10 inches in circumference where they emerged from his skull; I could not reach around the main beam at any point.

The 220-grain Corelokt bullet from the 8mm. Remington magnum had caught him in the “hump” just above the shoulder, severing the spine, and apparently all four legs had gone out from under him at once, creating a dust cloud as his massive weight plowed to a stop.

Back at headquarters a ranch biologist measured and scored the rack for the Boone & Crockett Club. Only “discount points” from the left antler kept him out of that record book. “You should have him scored for the Burkett Record Book,” said biologist Gary Wolfe. “This is about as big and as old an elk as they come, and the Burkett system rates them entirely on how big they are without deductions for lack of symmetry.”

Later, after the rack was measured by certified tropeologist John Wootters, and then remeasured and confirmed by tropeologist Frank Willis of Houston, I received notification that I had the number one world record elk in Burkett’s Trophy Game Records of the World.

It was five months later, during the worst winter in years in the high country, that the phone rang at my desk in Houston.

“A cowboy found old Crip today,” said Louis Kestenbaum sadly. “I guess he died from old age and the weather all alone up there on that same ridge where you and Sonny waited for him. His teeth were just about gone and we couldn’t tell for sure what had been wrong with his leg; looked like it had been that way a long time. He had a magnificent rack, very high and with seven points on one side, six on the other. Just thought you’d like to know.”

“Thanks,” I said, suddenly feeling a whole lot better about the Caribou. His teeth were about gone, too. At least he will occupy a place of honor, in memory and on the wall, for as long as I live.