Editor's Note: Longtime F&S whitetail columnist Scott Bestul passed away on April 19th, after a long battle with cancer. In memory of him, we will be republishing some of the Bestul's best work. Today's story highlights his no-b.s. reporting. Never one to ape anyone's marketing claims, Bestul instead put them to the test and reported the results without fear or favor. The story below is a perfect example, introduced here by F&S hunting editor, Will Brantley.

I once walked up to the counter of a local archery shop and noticed that cut-out pages of a magazine had been placed there, under the clear plastic, for everyone to see. It was late summer, the kid behind the counter was busy fletching arrows, and he said that he’d be right with me. I told him "No hurry," and I looked down at the article.

The cut-outs were from Field & Stream, and specifically from Scott Bestul’s Whitetails column. For that one, he'd enlisted the help of a drug-sniffing German Shepard to test whether or not various scent-killing products worked at destroying odor. To quickly summarize the results, those sprays didn’t fool the dog’s nose even a little bit. Scott reported it, and mentioned that a whitetail's nose is supposedly even better than a dog's. At the time, folks in the scent-control industry were infuriated.

That was the thing about Scott. He had all of the bona fides necessary to strike it rich as a hunting celebrity. He was tall, fit, and well-spoken, comfortable in front of a seminar crowd and in front of a camera. He'd killed not one but three Booner bucks with a bow, including one with a recurve, and who knows how many P&Y animals. Dave Hurteau, Scott’s longtime editor and mine too, often said that if Scott decided to pursue a particular buck, that deer was in trouble.

Year after year, often in September, Scott would prove that was true—but you damn near had to pry it out of him to get him to even admit he'd shot a buck. He’s one of the few great hunters I’ve met who absolutely never bragged. Probably, that’s one reason why he never became a hunting celebrity. But the other, and the bigger one, was that he wasn't going to promote a scent-killing spray or anything else that he didn't believe worked.

He told stories, reviewed products, and shared the techniques that had worked for him with 100% conviction. Sometimes, what he wrote would upset people who owned or worked for hunting companies. Scott didn't like for anyone to be upset with him, but that included his readers above all. If Scott wrote it, it's because he believed it to be true.

Scott was the first of the big-name writers that I got to know when I began writing for Field & Stream 17 years ago. We tested bows and crossbows together for a decade. Worked on books together. Co-wrote articles. Covered trade shows. Sipped a little whiskey. Talked deer and turkeys and food plots and life. He read stories to my son, Anse, when the boy was about a year old. About a month ago, Scott texted me an old picture of him holding my kid, the both of them smiling. Scott, sick in bed, had seen a picture I posted of Anse, now almost 11, smiling with a big gobbler that he'd killed this spring. He'd saved that old photo of the two of them for all these years.

“Time sure flies,” Scott said. And it does.

It's probably been 12 years ago now, since I saw that article under the plastic on the counter at that bow shop. The kid who'd been fletching arrows walked up, apologized for the delay, and asked what he could help me with.

I smiled and pointed at the article and asked him if he'd read it.

“I sure did. Man, that's a hell of an idea, getting a drug dog to test scent spray!" he said. "It sure makes you think."

“Yes it does," I said. "And you know what? I know that guy who wrote it.” —Will Brantley

Related: In Memory of F&S Whitetails Columnist Scott Bestul

The Sniff Test: Scent-Control vs Drug-Sniffing Dog

Every deer hunter frets about body odor. But our attempts to manage it are all over the map. Many of us shower or spray down. Then there are those whose pre-hunt deodorization routines border on obsessive-compulsive. I wanted to know if any of it really makes any difference. So, I left it to Chance—the German Shepherd K-9 partner of Luke Sass, a sheriff's deputy In Houston County, Minnesota. Chance not only sniffs out contraband drugs; he can find a lost person or track down a runaway crook. I asked Sass if he could try to find a hunter attempting to hide his b.o. “Absolutely,” he said.

Stinking Inside the Box

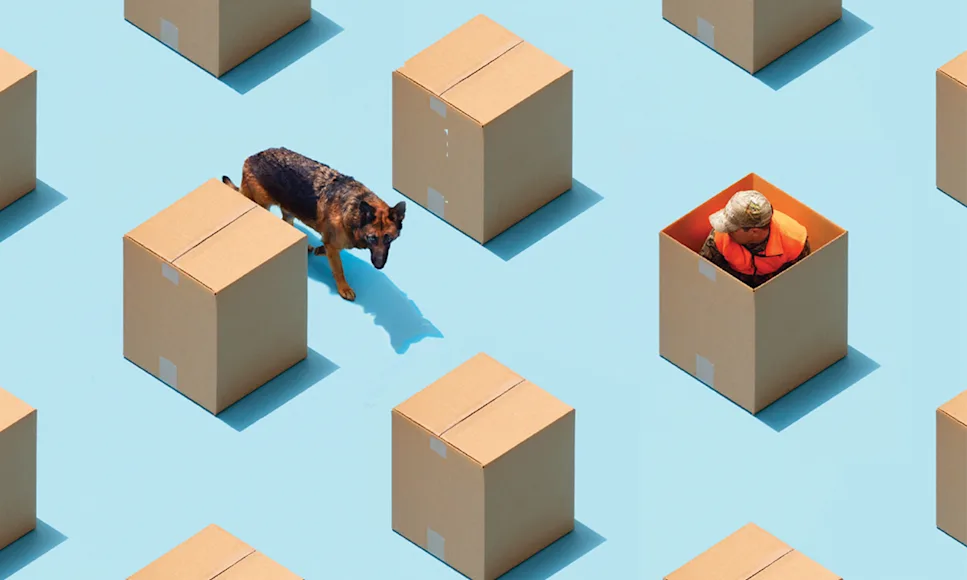

Like most K-9 cops, Chance learned to find people by playing the Hot Box game. Six plywood boxes (4x4x4 feet each) are spaced evenly in two rows across the field. People enter the boxes for two to three minutes to “heat them up” with human scent. Then all but one person exits. The dog's job is to sort through the residual human odor wafting from every box and pinpoint the one hiding the bad guy, or in this case, the hunter.

We conducted three simple tests to see if certain measures could confuse or perhaps completely fool the dog. For each, Sass walked Chance to one end of the rows of boxes, unclipped the leash, and commanded the dog to “find him.” Chance swung 15 yards or so downwind to sift through the scent clues. When he pinpointed the hot box, Chance stopped, barked, and leapt at the enclosure.

Test #1: Full Blown B.O.

Hunting buddy Bob Borowiak volunteered to be the dummy, er, hunter for the day. For the first test, Bob showed up stinky. He had not showered nor attempted any other scent-control measure. He wore street clothes, laundered in regular soap and wore his everyday tennis shoes.

The Result: From the moment Chance began his swing downwind, it took him roughly 20 seconds before he was barking at Bob's box. Once he winded the hottest enclosure, there was no hesitation. He moved straight to it.

Test #2: Showered and Sprayed

For the second test, Bob did his normal pre-hunt regimen of taking a no-scent shower and dressing in camo clothes washed in a no-scent detergent and stored in a plastic tub. He also wore high rubber boots to keep his walking trail clean and to hide foot odor.

The Result: It took Chance 18 seconds to find him. Again, there was zero hesitation.

Test #3: Compulsively Clean

Our final test involved every scent-control measure we could think of. In addition to the shower, Bob wore 2 layers of activated-carbon. clothing. I soaked him with scent-killing spray, and he chewed a wad of gum designed to eliminate breath odor.

The Result: It took Chance 13 seconds to find him. No hesitation.

Interpreting the Results

Sass, as well as fellow K-9 handler and bowhunter Tracy Erickson, was confident Chance would find Bob regardless of the scent-control measures. But we all expected a significant variance in the time it would take. If the measures had any effect, we assumed we'd see some hesitation on chances part, particularly given that the other boxes also contained human scent. But that didn't happen. As the test progressed, Chance got increasingly excited and perhaps ran a bit faster when swinging downwind. But once he got there, the time it took him to nail Bob was the same—more or less instantaneous.

Borowiak was bowled over by the results. But he plans to maintain his shower-and-spray routine on the prospect that it might have an impact upon how quickly or how hard a deer spooks. It’s understandable. We can't say for sure how a deer would react under the same circumstances. But what the experiment showed without a doubt is that all the scent-reducing measures in the world won't make a bit of difference to a downwind dog.

As with all dogs, Chance’s sniffer contains over 220 million olfactory receptor sites. And although it's unknown precisely how many are in a whitetail’s nose, it’s estimated at several hundred million. In other words, what a dog can smell, a deer should be able to smell even better. That fact, combine with our tests, suggests that at the very least, if a deer is downwind and reasonably close, he can smell you, no matter what. Period.

In a time when we are bombarded by testimonials claiming that product X makes downwind deer oblivious, our tests say: Probably not. According to Chance, If you’re a deer hunter thinks he can ignore the wind, you're barking up the wrong tree.

This story originally ran in the August 2011 issue of Field & Stream.