On January 8, the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) rejected petitions from Wyoming and Montana to remove long-standing Endangered Species Act protections from two separate grizzly bear populations in the Intermountain West. The rejection—issued in a routine rule-making process—means that fish and game agencies in Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana won't be managing grizzly bears through hunter harvest any time soon.

The petitions would have de-listed grizzlies in both the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE)—a vast area centered around Yellowstone National Park in northwest Wyoming—and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (NCDE)—16,000 square miles in northwest Montana that includes Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. In order to do that, the agency would have to determine that both of these areas are so-called "distinct population segments" or DPSs. In its press release, USFWS said the petitions were "not warranted" based on a "thorough review of the best scientific and commercial data available."

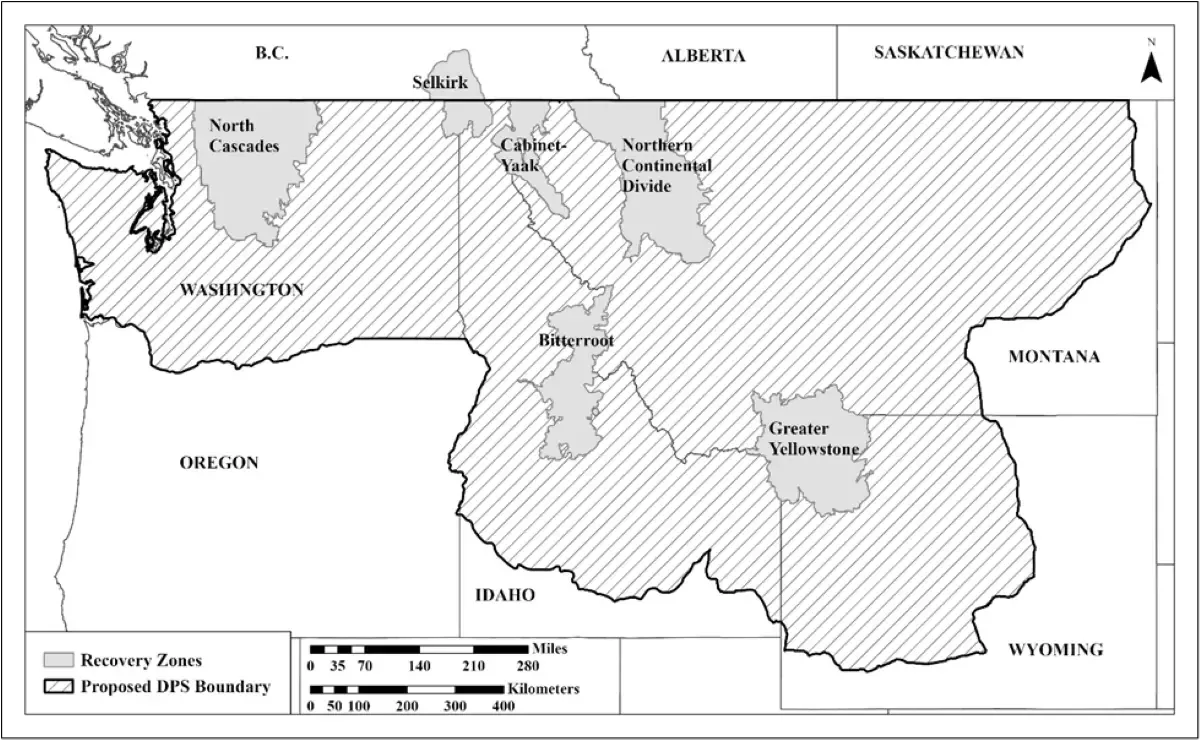

With its proposed rule change, USFWS will instead designate all grizzly bear populations in the Lower 48 as one single population segment. And those bears, which range through portions of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Washington, will stay on the Endangered Species List for the foreseeable future. The statement added that "grizzly bear populations in [the Northern Continental Divide and Greater Yellowstone] ecosystems do not, on their own, represent valid DPSs."

Grizzly bears were placed on the Endangered Species List in 1975. That's the year that the federal government established the individual recovery zones now known as the Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystems. According to USFWS's own data, grizzlies have met and far exceeded recovery goals in both of those ecosystems.

The Sportsmen's Alliance, an advocacy group that lobbies for hunting and trapping rights, says the recent rule change is designed to keep grizzlies under federal protection and out of state jurisdiction in perpetuity. "Fish and Wildlife has openly admitted that grizzlies have been recovered in these specific areas," Todd Adkins, the organization's Senior Vice President, tells Field & Stream. "The argument comes down to: What are the geographic areas that we're supposes to evaluate and ultimately de-list? And for Fish and Wildlife that is a constant moving goal post."

USFWS says the rule change would give state wildlife agencies and landowners in grizzly country additional flexibility when it comes to dealing with problem bears involved in human or livestock-related conflict. “This reclassification will facilitate recovery of grizzly bears and provide a stronger foundation for eventual delisting,” said USFWS Director Martha Williams in a prepared statement. “And the proposed changes to our 4(d) rule will provide management agencies and landowners more tools and flexibility to deal with human/bear conflicts, an essential part of grizzly bear recovery.”

Related: Mining Road Through Alaska’s Brooks Range Denied Again Thanks to Outcry from Hunters and Anglers

But the Sportmen's Alliance says that the unwillingness of USFWS to designate and de-list the fully recovered GYE and NCDE bear populations points to broader problems with the Endangered Species Act itself. “This shows that the Endangered Species Act is broken,” said Michael Jean, Litigation Counsel for Sportsmen’s Alliance Foundation in a blog post on the organization's website. “We have multiple populations of different species that have surpassed their recovery goals—and are thriving—yet they cannot be delisted, according to the service, because they have not fully recovered in other areas.”

Whatever the outcome may be, Adkins says that challenges to the USFWS's Jan. 8 rule change proposal are imminent. "This decision is going to get sued, and the Trump Administration will undoubtedly come in and make some rule changes of their own," he said. "But we just want to solve this problem for the people that have to live with the consequences."