WE’RE FLY FISHING one of the most famous rivers in the most famous place to fly fish for trout in the world—the Lamar River of Yellowstone National Park—and I’m getting skunked.

The conditions are admittedly poor. It’s noon on a bluebird day in mid-August, and a heat wave is sweeping the West. The water temps on the Lamar are high enough to make the trout sluggish, and the direct sunlight doesn’t help, either. But I’m with six other anglers, and most have brought fish to hand. Challenging conditions aside, I’m just having an off day. Twice, I get a fish to rise to a foam beetle, but I miss each time—first by setting too slowly, then by swinging too hard and breaking off.

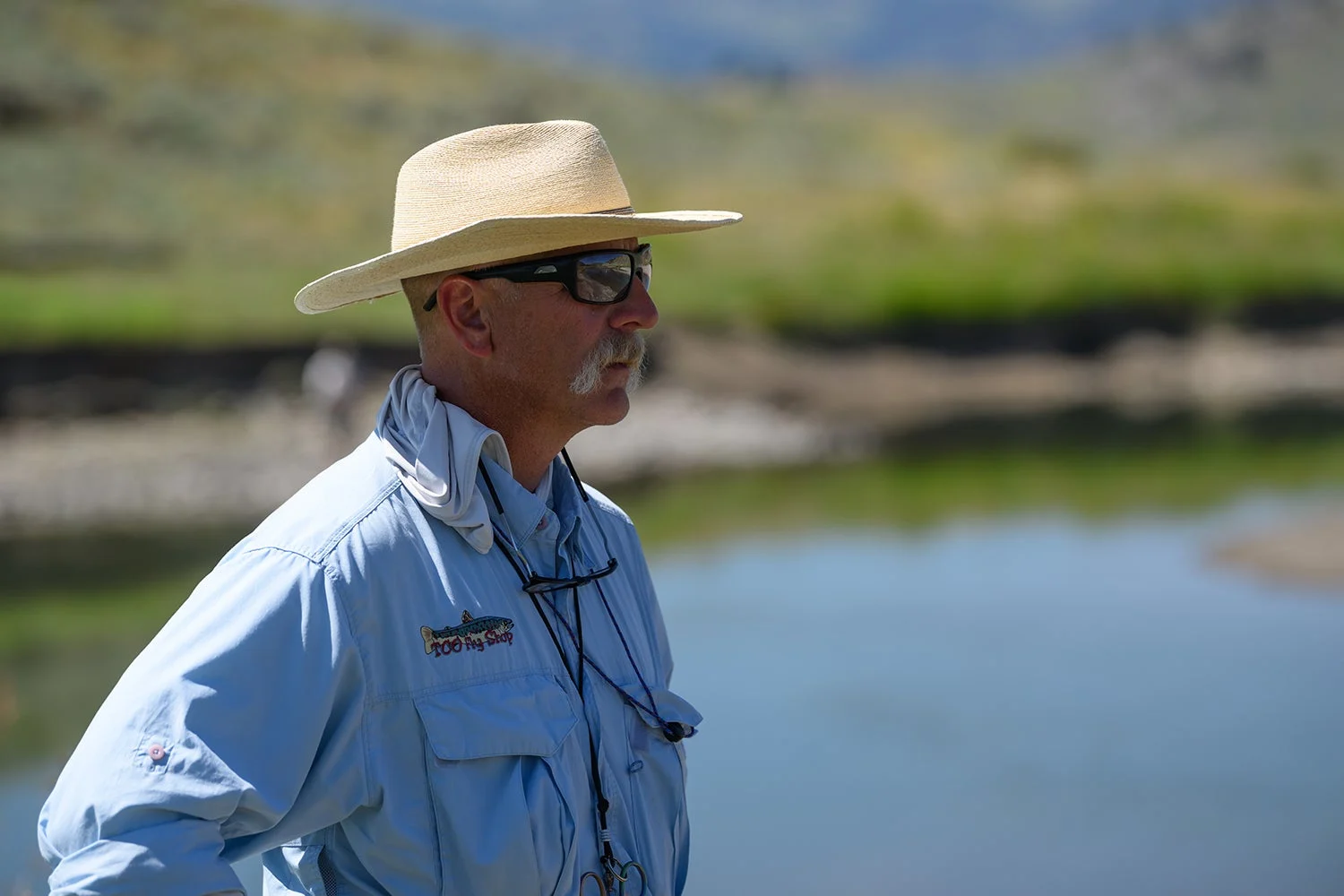

Paul Weamer surveys the river. Bill Buckley

My anxiety builds. I’m participating in a unique park-sponsored citizen science project dubbed the Volunteer Fly Fishing Program, which enlists average-Joe anglers like myself to monitor and tag native trout while removing nonnative species. This summer, the program was revived after a seven-year hiatus caused by budgetary issues, the pandemic, and 2022’s unprecedented flooding. I want to contribute to the tag-and-release surveillance program we’re working on today by registering a fish of my own. But to do that, I first have to catch a fish.

The other volunteers are members of Tri-Valley Fly Fishers, a club from California’s Bay Area. They’re all retired and have already developed ties to the fishery. I’m the only one in the group visiting the park for the first time. Beyond tagging a fish, I’m intent on landing my first Yellowstone cutthroat.

A group of bison add some wild scenery along Slough Creek. Bill Buckley

“We’ve still got to hit the top of the beat to say we’ve covered the whole thing before we head home,” Paul Weamer, the program coordinator, tells me. “Would you mind going up to the runout beneath those boulders? In the past, there haven’t been many fish in there, but you never know.”

“Sure,” I say. When I reach the new spot, I clip the terrestrial and tie on a Rubber Legs with a Hare’s Ear dropper. I fasten a bobber to the leader and cast it next to the boulder, where it swirls once in an eddy.

Then it drops.

Trophy—and Troubled—Waters

Invasive species have been threatening Yellowstone’s native fish—Yellowstone and Westslope cutthroat trout and arctic grayling—since shortly after the park’s inception in 1872. In 1889, park managers began stocking nonnative brook, rainbow, and brown trout to appease commercial and recreational fishers. Some of the fish were planted in historically barren waters, while others were stocked in cutthroat and grayling habitats. The nonnatives quickly preyed on, hybridized, and outcompeted native trout populations throughout much of the park. Scientists are not able to accurately quantify the full extent of those impacts on the park’s waterways, but by the time fishery managers realized the unintended damage of the stocking program and discontinued it, in the mid-1950s, 16 million nonnative fish had been planted. The introduced fish established self-sustaining populations in most of the park’s lakes and larger streams, except for parts of the Yellowstone, Lamar, and Snake Rivers, as well as Yellowstone Lake.

Fishing conditions were tough during the volunteers’ mid-August trip, but this angler still managed to catch a nice cutt. Bill Buckley

Then, in 1994, another major threat to the native fish was detected when lake trout were found in Yellowstone Lake. They aggressively preyed on, and reduced, the lake’s migratory cutthroat trout. By 2007, the run of migratory cutthroat at one of the lake’s tributaries plummeted from 70,000 fish to around 500.

For the past 20 years, Todd Koel, the park’s head fisheries biologist has led the charge to conserve the native trout, largely by fighting to reduce the nonnative populations. He describes it as a drawn-out, multi-pronged war. As field general, Koel has managed a team of fisheries biologists and technicians who regularly use rotenone, a fish-killing pesticide, to rid headwater streams of invasives; deployed a massive gill-netting operation on Yellowstone Lake to knock back the lake trout; and founded the volunteer fly-fishing program in 2002—the first citizen science fishing program of its kind at a national park.

Detailed notes and measurements of a trout are taken before it is tagged and released. Bill Buckley

Koel created the novel program because the park’s 2,500 miles of moving water are so challenging to effectively monitor with his small team of scientists, especially since parts of it are so difficult to access. On the Lamar River, for instance, the typical way to monitor the fishery would require using a helicopter to fly in a raft outfitted with electro-shock equipment. Compared to that, volunteer fly anglers are cheaper—and, according to recent studies of sampling methods conducted in the park, just as accurate.

This year’s program comes on the heels of the most disturbing news for Yellowstone’s native fish since the detection of lake trout in Yellowstone Lake in 1994: In February 2022, an angler fishing the confluence of the Gardner and Yellowstone rivers in Gardiner, the doorstep of the park, caught a smallmouth bass. It was the first time a bass had been caught so close to the renowned trout fishery, posing a potentially devastating threat to the park’s native trout.

The anglers head back to their cars after hot midday temps kill the fishing. Bill Buckley

I met Koel while reporting on the smallmouth bass detection, and he invited me to visit the park to participate in the volunteer fly-fishing program. I jumped at the chance to observe some of the park’s on-the-ground conservation efforts—and to fish a bucket-list destination.

A Team Effort

When my strike indicator drops, I set the hook. It’s a nice fish, but the fight is characteristically brief for a cutthroat. The trout shakes its head without making any real runs. In less than a minute, I bring it to hand, dump it in a collapsible plastic bucket, and speed-walk downstream. Catching it is one thing. Now we’ve got to get it documented and safely released.

When I reach Weamer, he grins and fist-bumps me. His enthusiasm feels genuine; it’s no surprise he spent years as a fishing guide before taking over as program coordinator. Weamer, in his 50s, is wearing a wide-brimmed straw sun hat. He puts the trout in a makeshift livewell, a mesh laundry basket secured to the riverbed with a heavy rock, and lets it recover.

A tagging gun is loaded with Floy tags. Bill Buckley

To my eye, it looks like a classic Yellowstone cutthroat, with a burgundy gash beneath its jaw and a tint of gold on its speckled side. But when Weamer inspects it, he finds signs of hybridization. Recent genetics testing by a Montana State Ph.D. student shows that excessive spotting on the head and white markings on the fins are clear indicators of hybridization. My trout exhibits both characteristics.

But since the fish is part of a sampling study, we’re still going to tag and release it instead of cull it. Weamer measures the fish on a piece of PVC pipe, notes the exact GPS coordinates of where I caught it, and inserts Floy, or T-bar anchor, tags just behind the dorsal fin. I stand with the clipboard and jot down each number (386 millimeters sounds cooler than 15 inches). I’m disappointed I didn’t catch a pure cutthroat but glad that I managed to contribute to the effort.

Minutes after letting the fish go, I have another trout on. It’s about the same size as the first and, to my untrained eye, looks just like it. But when Weamer inspects my catch, he nods his head. “It’s a classic Yellowstone cutthroat trout,” he says. “This fish will always be associated with you. If it’s ever documented again, it will be traced back to today.”

We record the fish’s information and tag it. Then I hold the trout in the water for a moment before releasing it. I notice the orange Floy tags waving in the current. It feels bittersweet to have marked such a beautiful fish this way—but mostly I’m proud I caught it, and even prouder to play some small role in conserving the species for others to do the same. The cutthroat rests a moment longer, then splashes its tail once and disappears back into the Lamar.

Getting Technical

The second day of fishing is even slower. This time, we’re supposed to work a beat on Slough Creek—another renowned waterway in the Lamar Valley. But it’s even hotter than yesterday, and the water is slow and mostly featureless, which gives the trout ample time to inspect, and reject, our flies.

I spot a couple of trout finning in a shallow pool and fire a cast at them. I get one of them to take my Perdigon dropper, but it gets off. The fish are otherwise remarkably spooky. It’s not the fast-action dry-fly fishing the park is renowned for.

Weamer prepares to net a trout. Bill Buckley

After a couple of fruitless hours, I step back and take in the scenery. A massive herd of bison is working its way down the far shore—the pre-rut bulls snorting, grunting, and wallowing in the sand. I scan the sage-covered hills, hoping to catch a glimpse of a wolf or grizzly bear but spot only a few pronghorn working away from us. Still, there are worse places to get skunked.

And not everyone is striking out. Rob Farris, a 74-year-old retired Silicon Valley executive, is the first on the board. He cycles through several small mayfly patterns before getting a slender cutthroat to bite. It’s the first pure cutthroat he’s caught on the trip. Then Mitchie McCammon, 59, fools a cutthroat with a beetle pattern. It’s the biggest one so far.

Meanwhile, I decide to take a break to chat with Weamer. It’s his first year heading up the program, and he’s already faced several challenges. Some of the volunteers are not clear about their physical limitations when they sign up, which can pose a serious challenge since most of the fishing spots are reached by hiking through miles of rugged terrain. Other volunteers—myself included—struggle with the pressure.

“It’s one thing if you go fishing on your own and don’t catch anything,” he says. “People are usually bummed. But they feel worse when it happens when they’re doing the program. They feel like they let the program, science, and Yellowstone down. I remind them that we learn all kinds of things just by them being here.”

A pair of volunteer anglers spot some feeding cutts. Bill Buckley

He also told me that some anglers struggle with dispatching invasive fish. “Most of us are not used to killing trout. Sometimes, they’re hesitant when I have to dispatch a rainbow, which is the law in some parts of the park. I tell them if we don’t do something, there won’t be any more Yellowstone cutthroat trout. They usually understand.”

For the rest of the day, we don’t catch any rainbows, or any other trout. By 1 p.m., it’s blisteringly hot, so we quit early. But on the walk back to the parking lot, the other anglers, who’ve driven thousands of miles and paid for their lodging to be here, don’t seem discouraged. They’ve done what they came to do.

“The wildness of that fish was just phenomenal,” Farris says, reflecting on his catch. “It’s why I came on this trip. You can’t always take without giving back, or the resource won’t be there for you, your kids, or their kids. If I don’t give back, who will?”

Hopper Frenzy

During my two days with the volunteer fly-fishing program, I got a small taste of what’s so special about fishing in Yellowstone. But I’m hungry for more. Following Weamer’s suggestion, I decide to try a new spot upriver on the Lamar the next morning before hitting the road.

It’s a good thing I do.

Early in the session, cutthroat trout start drilling my foam hopper on every other cast. Most are dinks, but I manage several that push 16 inches, though I don’t bother measuring them. According to the criteria that Weamer taught me, they all appear to be Yellowstone cutthroats. The lights-out fishing makes for the kind of morning that’s few and far between anywhere else in the world.

So far, Yellowstone’s fishery has avoided a worst-case scenario. Years of systematic gill-netting efforts have knocked down Yellowstone Lake’s invasive lake trout population, allowing the watershed’s cutthroat trout to bounce back. The biologists’ localized use of rotenone to remove nonnative trout from headwater streams and restore native fish has worked—though in some cases, nonnatives have proven difficult to fully eradicate. Hybridization remains a major issue, especially in the Lamar, but pure cutthroats like the ones I’m catching today still abound. Koel and his team sampled the river near where the smallmouth bass was detected in 2022 but didn’t find evidence of any other bass. Since then, no one has caught any in Paradise Valley or the park, though Koel worries it may be only a matter of time.

One thing is clear: The famed park’s native fish deserve protection. Also, whenever the next major threat emerges, anglers in the volunteer program and beyond will arrive and do whatever they can to help, fly rods in hand.

I know I will.