_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

Several years ago, down in Colorado, I was prone behind one of my long-range competition guns, the scope’s crosshairs steady on the ribcage of an antelope feeding on a sage-covered hill nearly 500 yards away. This better work, I thought.

Before that moment, I’d had a pretty fixed notion of what made a proper big-game bullet. Whether I was chasing Coues deer in Mexico, bears in Alaska, plains game in Africa, or whitetails in the Midwest, I wanted my bullets to more or less behave the same. That is, to punch through hide and bone, mushroom on contact, and retain the majority of their weight as they penetrated.

If I were to rattle off all the bullets designed to meet these parameters, I’d run out of room in this column before completing the list. The point being, this view of what a hunting bullet is supposed to accomplish has been nearly universally shared by sportsmen and bullet-makers no matter whether the projectile in question had a lead core chemically bonded to the jacket, was extruded from a solid piece of copper or copper alloy, was topped with a polymer tip, or was formed using a basic cup-and-draw method that was common during your great-grandfather’s time.

However, in the last 12 years or so, a growing number of hunters began to challenge this orthodoxy. These long-range shooters were taking practical rifle accuracy to new extremes. They reasoned that if they could go 10 for 10 at 1,000 yards on steel targets the size of a deer’s vitals in shifting winds, wouldn’t a 500-yard poke on a mule deer amount to a chip shot?

For them, accuracy is paramount. And the only way to guarantee accuracy at long range is with match bullets.

How Has Match Ammunition Changed?

Had I in my younger days showed up at deer camp with ammo tipped with match bullets, I would have been flogged. Like pouring Coke over good whiskey, hunting with match bullets is one of those things that simply wasn’t done.

And yet I kept hearing glowing reports from friends I respected about how match bullets performed on game. I’d heard some horror stories too about animals that got away, but those all seemed to revolve around very long shots where any bullet might have come up short.

Though I still had some serious reservations about hunting with target bullets, the anecdotal evidence indicated my concerns might be overblown. Eventually, I decided that if I were to have an informed opinion on the matter, I needed to see for myself how competition bullets fared in the field. Which is how I found myself on my belly preparing for a shot on that antelope in Colorado.

My rifle was a 6mm Creedmoor built by George Gardner at GA Precision. My competition load at the time was a 105-grain Berger Hybrid over 42.2 grains of H4350. The rifle was (and still is) a hammer. At 500 yards, it’ll put shot after shot into the lid of a coffee can.

That kind of precision is what advocates of hunting with match bullets say is the redeeming quality of the practice: perfect control over bullet placement.

My bullet went right where it was supposed to, and the buck fell. My friends, who also had tags, shot three more antelope that day at distances of 300 yards or more with that rifle-and-bullet combo, all with the same results.

When my son started hunting deer at age 10, he used an AR-15 of mine that I shot in 3-Gun competition. With 77-grain OTM (for open-tip match) bullets in .223 Rem., it’s a tack-driver. He killed two nice Nebraska whitetails that season and went on to shoot many other deer with those bullets. I was so impressed with how it performed that I used it on a couple of whitetails over the years as well. At this point, I’m not sure exactly how many big-game animals I’ve shot—or seen shot—with match bullets, but it is somewhere north of 20.

With the 105-grain Berger Hybrid, that includes several large mule deer bucks and stout corn-fed whitetails. I’ve also shot a handful of deer with a .260 Remington using the 130-grain Hornady ELD-M and 130-grain Sierra Tipped MatchKing.

Shot distances have ranged from more than 500 yards down to about 30 feet. As for terminal ballistics, the bullets have all fragmented violently, and while I’ve gotten a couple of exit wounds, for the most part the bullets have remained in the animals. None of these critters made it very far after being hit. One mule deer ran about 50 yards before piling up in the grass, and that’s the longest distance between impact and death I can recall.

Can Hunters Use Match Ammo on Game as Big as Elk?

Despite this perfect track record, I still have some reservations. I haven’t shot an elk with match bullets, mostly because I prefer to hunt with lighter calibers, and I think taking on elk or other large-bodied game with a thin-jacketed match bullet in those cartridges is courting trouble. That said, I did see one bull elk killed by a first-time hunter, a 13-year-old boy, using a 140-grain A-Max from a 6.5 Creedmoor. That isn’t a bullet I’d recommend for the task. Being inexperienced, he put the crosshairs right on the point of the shoulder and let fly. The bullet took out both front wheels (and a lot of good meat) on that elk—a big-bodied 6×6 satellite bull. It couldn’t have been any deader. Back at camp, I poked around in the carcass looking for bullet fragments. All I found was the red polymer tip in the mess of the off shoulder.

Over time, I’ve changed my mind about hunting with match bullets. While a traditional hunting bullet is more forgiving in terms of shot angle and breaking through heavy bones, that is balanced out—for the most part, anyway—by the better control over shot placement you get from match bullets. Both are useful tools, and are deadly effective when they’re used the right way.

But even though I now include match bullets in my repertoire for hunting, I’d still rather die of thirst before adding a drop of Coke to good whiskey.

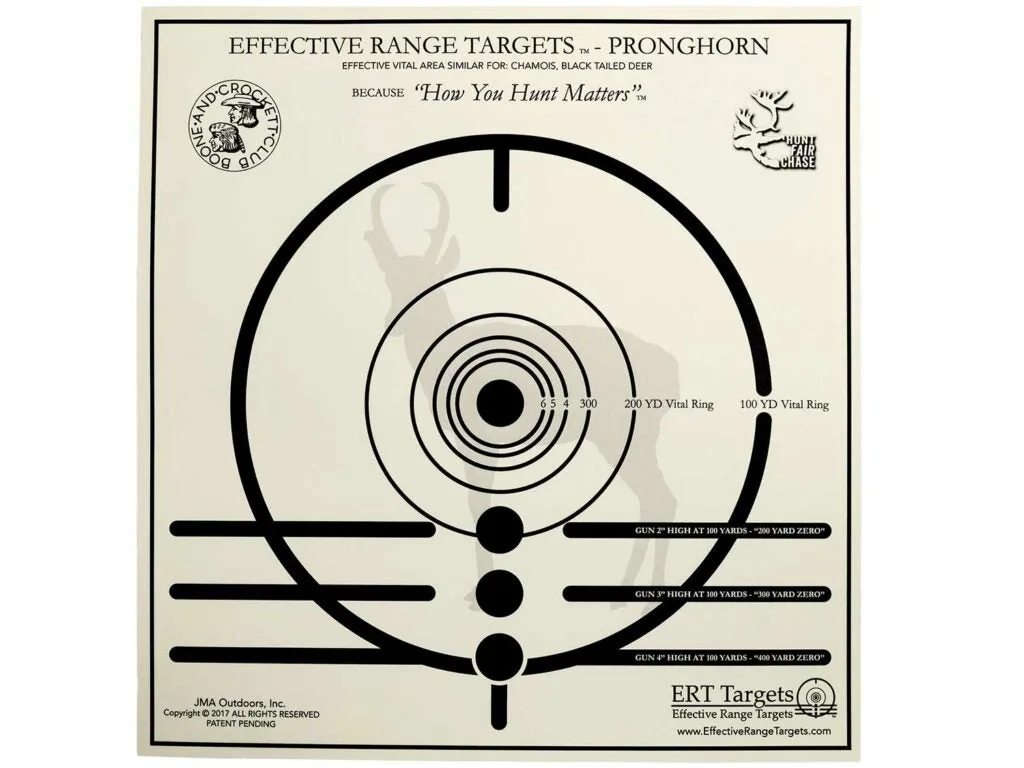

Effective Range Targets for Pronghorns. Effective Range Targets

New ERT targets

can help you determine your maximum effective range on game. They are species-specific, with a series of circles that correspond to the vitals zone of the animal at different distances. You shoot them at 100 yards from a practical field position, like sitting using shooting sticks. If you can’t group all of your shots in the 300-yard circle, you know you have no business hunting at that distance. They are great motivators to practice more.

This story originally appeared in the October-November issue of Field & Stream.