“The Art of Flippery” by Ted Trueblood, first appeared in the January 1963 issue. Trueblood was the original Total Outdoorsman—skilled in hunting, fishing, and, as you’re about to read, flinging a slingshot.

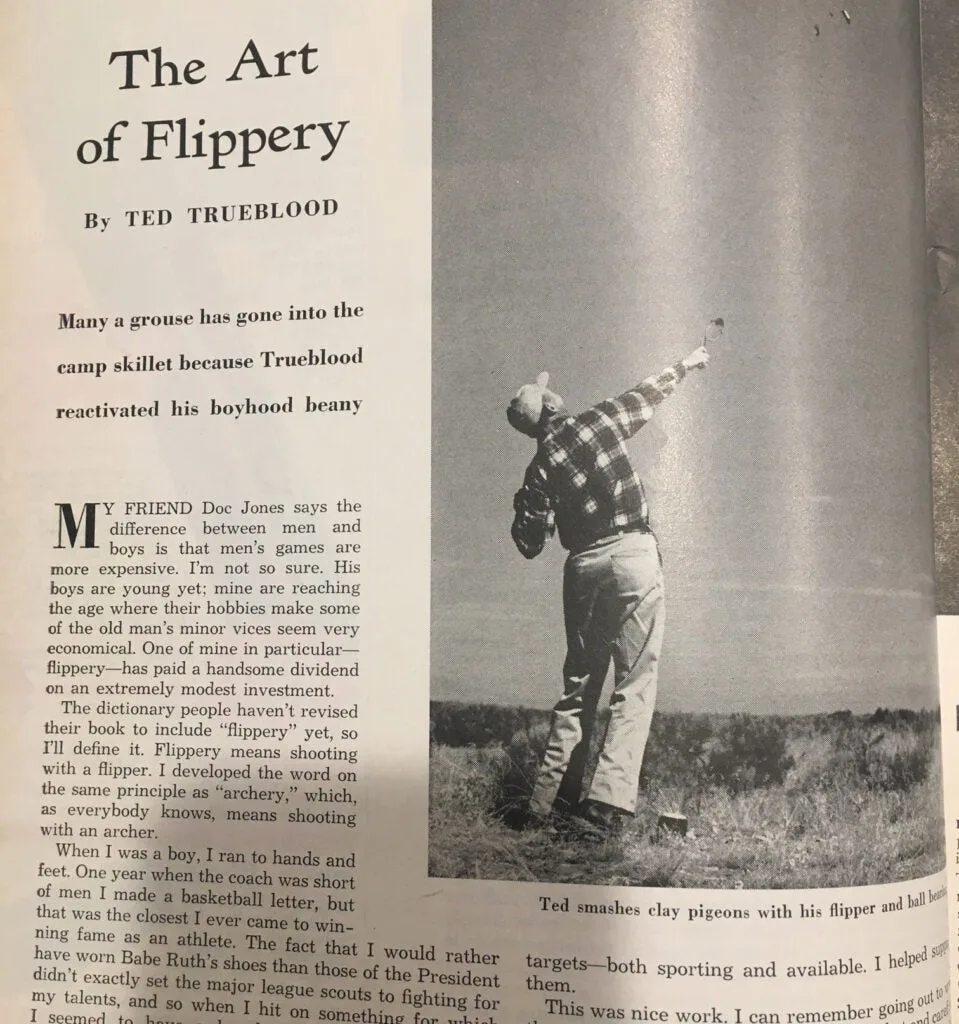

Ted Trueblood fires his flipper (aka slingshot) for this classic column. Field & Stream

MY FRIEND DOC JONES says the difference between men and boys is that men’s games are more expensive. I’m not so sure. His boys are young yet; mine are reaching the age where their hobbies make some of the old man’s minor vices seem very economical. One of mine in particular—flippery—has paid a handsome dividend on an extremely modest investment.

The dictionary people haven’t revised their book to include “flippery” yet, so I’ll define it. Flippery means shooting with a flipper. I developed the word on the same principle as archery, which, as everybody knows, means shooting with an archer.

When I was a boy, I ran to hands and feet. One year when the coach was short of men I made a basketball letter, but that was the closest I ever came to winning fame as an athlete. The fact that I would rather have worn Babe Ruth’s shoes than those of the President didn’t exactly set the major league scouts to fighting for my talents, and so when I hit on something for which I seemed to have a knack, sticking to it was only natural.

I discovered, probably in the fourth or fifth grade, that I could hit things with it being flipper. That was in the days when the Model T had yet to prove its superiority over the horse. We farmed with horses—I doubt if there are a dozen farm boys in the country now who could harness a team—and the English sparrow was at the height of its glory. He was a pest. There were millions of sparrows. People trapped and poisoned them, but they throve in spite of this persecution, and they made ideal targets—both sporting and available. I helped suppress them.

This was nice work. I can remember going out to weed the garden with a beany in my pistol pocket and carefully selected pebbles in another, and it was a rare day when I didn’t knock over a sparrow or two. The best hunting came about school-out time, just after the young birds had left the nest. They could fly, of course, but they were less suspicious than the adults, most of which had been shot at before. I made some pretty big bag then.

My father wouldn’t tolerate killing songbirds or blackbirds, which he considered beneficial, although they were not protected by law. Legal targets were English sparrows, magpies, crows, snakes, and frogs, but the sparrows were handy, abundant, and pestiferous, so naturally I shot more of them than anything else.

I had a gun in those days and also suffered with archery for a while, but the beany got more use. I could carry it in my pocket; ammunition was free and made no noise; I didn’t have to chase arrows; and I was more accurate at close range with the flipper than I was with a bow.

The time eventually came, of course, when I laid my beany aside. Like all other boys, I had to pass through the ages—the important age, the dignified age, the girl age, the serious age, any ambitious age. After I had recovered from this foolishness, I was down at the home place one day and got to rummaging through a bin where my mother had put a lot of boyhood things. I found my old beany. The rubbers were rotten, but the leather pouch and the crotch, which I had cut from an apple tree, were still good. I decided to fix it up.

That was one of the best things I ever did. My boys got interested when they were about eight and 10, and I help them get started. Sometimes in camp we hang up a tin can on six feet of string, and at a range of twenty-five or thirty feet we can keep it swinging like crazy. We don’t hit it every time, of course, but we do connect often enough to make the competition pretty keen. Aerial targets are tougher, but not too difficult, and something that breaks when hit—a clay pigeon for example—is ideal.

I’ve probably killed more grouse with my flipper than any other kind of game.

I usually take my beany along in my tackle box when I go fishing. Sometimes I don’t use it, but occasionally it pays its way. I’ve killed several rattlesnakes with it. And one day three or four years ago the bass were most unappreciative and we finally went ashore to take a snooze. I didn’t get to sleep, however. The Willow ticket where we beached the boat was full of young magpies. They can fly as well as the old ones, which left at once, but they didn’t know the facts of life. I corrected that. The ones that survived had no doubts about man’s being there enemy.

When I was a boy, the toughest problem was finding good ammunition. We used to sort out pebbles, using only the roundest and smoothest, but even so it was impossible to get them perfectly uniform. One might curve to the left and when we corrected for that the next one would curve to the right. If Lady Luck didn’t happen to be on our side we had to do an awful lot of shooting to get many sparrows.

Of course there were marbles, but they were expensive then. Now that I am rich and can afford to flip away a bag of them anytime, I can probably shoot better than when I was in the eighth grade and practiced every day. Marbles always fly true. You soon learn how to hold and you can make corrections for windage from shot to shot.

In flippery, as in archery, there are two styles of shooting. One is instinctive: you just shoot. Practice eventually gives you the feel of your weapon and you develop surprising accuracy. The other style calls for aiming. I wouldn’t know how to aim an arrow, but if you hold the beany crotch in your right hand and pull to your ear with the left, you aim over the right fork with your left eye. I don’t aim. Instinctive shooting is faster and probably equally accurate after a little practice.

“Marbles aren’t very lethal. A half-inch ball bearing is ideal, and so pretty that a squirrel shot with one must feel flattered.” Señor Salme

Marbles are ideal for all kinds of fun shooting, but they aren’t very lethal. Warren Page would say they have poor sectional density: they’re too light and the velocity falls off rapidly. Lead balls—Jack DeMotte gave me a bullet mold to cast beany ammunition—are much better. My bass fishing buddy, who is a mechanic, saves ball bearings for me. A half-inch ball bearing is ideal, and so pretty that a squirrel shot with one must feel flattered.

I’ve probably killed more grouse with my flipper than any other kind of game. Where we hunt big game the grouse season is also open. There is no better camp meat than a big blue grouse of the West, but bagging them presents something of a problem. You can’t go blasting around with a high-power rifle or you’d spoke all the game out of country. You can’t use a shotgun for the same reason, even if it were feasible to take one along.

Some of the boys use a .22 rifle or pistol or a pellet gun to kill grouse, but they are heavier to carry and no more effective than my beany. In the back country a grouse can usually be depended upon the fly up into a tree and look at you. That is all it takes.

When I first started shooting grouse shortly after finding my old flipper and entering my second childhood, I had the idea that I’d have to hit them in the head to kill them. This sometimes took a lot of shooting unless they were close. Then I accidentally clouted one in the ribs with a ball bearing and when I picked him up I realized that I’d been doing it the hard way. If a body shot doesn’t kill the grouse outright it certainly shakes all thoughts of leaving out of his mind and gives you time to wring his neck.

In the old days, we used to cut our beany rubbers out of inner tubes, but modern inner tubes won’t stretch any farther than modern money, so I had to find a substitute. It turned out to be rubber surgical tubing, which is better than inner tubes ever were. It’s impossible to give the best size because this tubing varies in both wall thickness and diameter—3/8-inch tubing with thick walls is stronger than ½-inch tubing with thin. Also, some shooters can use a heavier pull than others. Quarter-inch tubing makes a gentle flipper, about right for stimulating the neighbor’s cat or shooting at tin cans, but in the larger sizes the only way to tell whether you’re getting the right strength is a double a piece and stretch it.

Rubbers that are too strong are a mistake. Like a bow, a flipper with too heavy a pull is no fun to shoot and it also hurts accuracy. One of my beanies was made with thick-wall 3/8-inch tubing and it has a pull at twelve inches of 26 pounds. This is too much for me if I fire more than a few rounds at a time.

Unlike a bow, a beany tips back when you pull it, and holding it square puts quite a strain on the wrist. Also, you can’t hook your fingers around the bowstring; you have to hold the pouch between the thumb and forefinger. As any archer knows, you can’t draw a very heavy bow this way. Because of these two differences, a flipper with a 20-pound pull is probably as hard to shoot as a bow with a pull of 45 or 50 pounds.

You can probably buy a better beany then you can make. Two or three are advertised regularly in Field & Stream. I’ve always made my own, however, and enjoy doing it. Finding a suitable crotch isn’t difficult, and one and 1-1/2×4-inch rectangle out of an old hunting shoe makes a good pouch. Slip the rubber tubing down over the ends of the fork, run it to the holes at the end of the pouch, double it back, and wrap it tightly with rubber while holding it stretched tight. Don’t tie the rubbers with cord; it would soon cut them.

In shooting, get the crotch well down in your hand. Brace one fork with your knuckle and hold your thumb against the other—and keep it square to the line of pull. You’ll bounce the missile off the back of your hand if you don’t. Avoid twisting the crotch, too. When you do this you’re almost sure to hit yourself on the thumb, an experience you’ll remember.

In all my years of flippery, I have had only one accident. I was visiting a farmer friend one day and he said, “I wish you’d shoot that old white rooster. He’s too wild to catch in the daytime and he roosts in a tree so I can’t get him at night.”

I got within 20 feet of the unsuspecting fowl and drew back to let him have it on the back of the head. Unfortunately, I was smoking my pipe. I didn’t smoke a pipe when I was a boy, so I hadn’t learned this lesson. As the beany pouch went by it caught the bowl. The bowl left and so did the rooster, but I still had the bit in my teeth.

_Read more F&S+

stories._