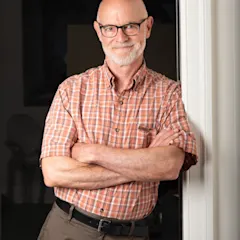

JIM MASSETT thinks the buck we’re tracking is a poser. A big track almost always means a big buck, and this track is definitely big. But the 80-year-old North Woods tracker has come across a few small bucks with big feet and big bucks with small feet. So he’s leery.

It’s an overcast, windless November afternoon in a hemlock forest near Old Forge, New York, in the 6-million-acre Adirondack Park. An inch of new snow fell last night, covering 3 inches of harder stuff. Normally, this kind of day has a brooding, melancholy feel. But being on a fresh track has a way of making things vivid, almost urgent. There’s a whole drama unfolding at our feet if you can tease out the story. Or you’re with someone who can.

Massett bids me to hunker down and look at the track the way he is. Using his finger as a measuring stick, he calls my attention to how it’s no deeper at the back than at the front. “Does and young bucks tend to walk on their toes,” he says. Older, larger bucks tend to walk on their heels, just like older people. The fact that this buck’s track is flat makes Massett think he’s not especially big. There are a couple of other things too. The stride is average in length. And the distance between the left and right prints—what he calls the stagger—is also average. A good Adirondack buck’s stagger will be 25 percent wider than a doe’s, and this one’s isn’t.

Only a small percentage of modern hunters chase deer like this—by getting on a track and following it until the deer is dead or the hunter runs out of daylight. I sure don’t. I spend hours fighting boredom in a tree stand, hoping something will show up. It makes no sense to hunt that way here, though, where deer densities can be as low as one or two animals per square mile. Massett has been tracking whitetails in the Adirondacks and a few other places for 70 years. In that time, he has taken more than 100 bucks, with an average age of 6½ years.

Generally speaking, he says, does wander while bucks head directly for a destination. When a buck’s track starts to meander, it usually means he is browsing just before bedding down—and that you are now within 50 yards of him. This is where 80 percent of hunters blow it, because it’s almost impossible to move too slowly. Massett will wait as long as 15 minutes between steps when he thinks a buck is close. One of you is going to make a mistake, and most of the time it will be you. That’s OK, he says. You wait a while, get back on the track, and the game restarts. Personally, I can’t imagine a more exciting way to hunt.

We come to a place where the buck we’re following paused to eat mushrooms off a downed tree. Massett points to where the snow has a slightly different texture. “See?” he says excitedly. “His rack brushed the snow while he ate. But it’s only about a foot wide.” The snow looks undisturbed. Or, if touched, then only by a puff of air. To me, what Massett is doing approaches witchcraft.

At a place where a slope heads up to a ridge, the sign shows that the buck we are on was joined by a bigger one. The tracks split up, and we follow the latter. Halfway up the hill, Massett slaps my shoulder. “Now that’s a big buck for you,” he says. “Don’t you see?” Nope. No, I don’t.

“He was on a path that would have taken him between these two saplings, but he went around them.” The trees are about 18 inches apart. A buck knows to the fraction of an inch how big his rack is, Massett says. If he walked around an opening like that, he’s a big one.

The light is starting to disappear, as if mopped up by the clouds. Massett used to track until the end of legal light and then hike for miles back to camp in the dark. Not anymore. I’m a little younger than he is, but still north of 60. Reluctantly, we leave the track and head home. “Tell you what,” he says, pointing up the hill with his chin. “I’m too old to be after them this hard. But that’s a buck worth working for. He might be bedded right up that rise. If I was your age, I’d be right there at first light.”

_This story originally ran in the Classics Issue

of_ Field & Stream_. Read more F&S+

stories._