I didn’t see the pair of mallards until they were on top of me. I was hidden in the shadows behind a small bush when the birds swung over my left shoulder. By the time I turned toward the creek, they were hovering over the decoys. I picked out the drake and folded it. When I reached down to grab the greenhead out of the cattails, something didn’t look right. My mind immediately went to a topic that I was in the middle of researching: Is this greenhead part farm-raised mallard?

Back in August, a conversation I had with waterfowl researcher Dr. Michael Schummer of SUNY-ESF led me to a multi-month deep dive into the impact of farm-raised mallards on Atlantic Flyway wild populations. Through that research, I learned about a few identifying features that may indicate farm-raised genes, like longer legs, wider bills, and plumage discoloration. Some of these characteristics were consistent with this New York mallard. So, I contacted Dr. Mike Brasher from Ducks Unlimited, and he put me in touch with the relatively new duckDNA program. DU mailed me a kit to send in a tissue sample of the mallard.

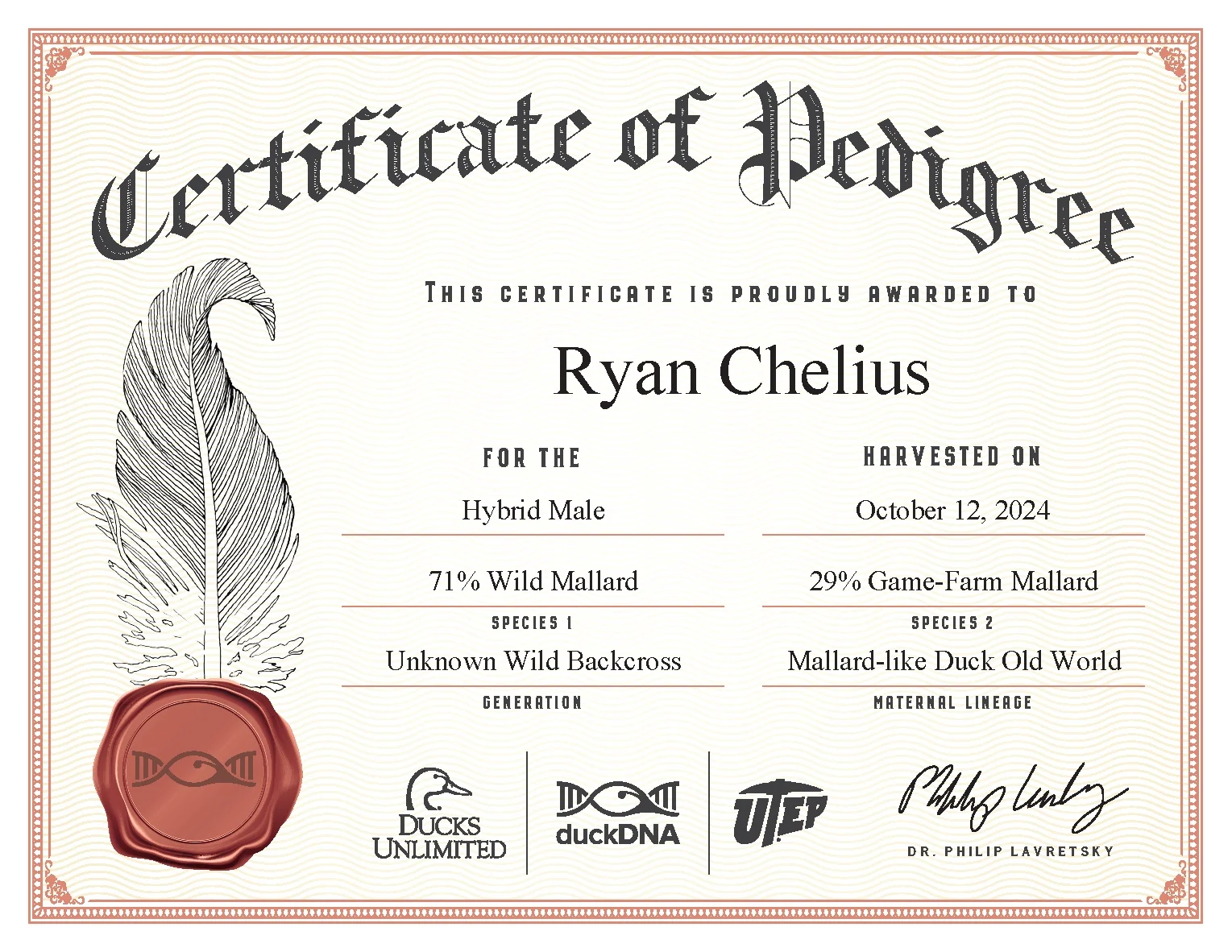

Three months later, I got an email that my results were in. I received a pedigree certificate that broke down my opening day greenhead’s genetics. Turns out that my hunch in the field was right, the mallard had significant traces of farm-raised DNA. You can also find out if the mallards you’re shooting are truly wild birds with a simple DNA test. Here's how.

What You Need to Know About the Farm Mallard Issue

If you haven’t been keeping up with the farm-raised mallard problem in the Atlantic Flyway then you might be surprised to hear that many East Coast greenheads aren’t fully wild. What does fully wild mean? Researchers found that mallards with more than 30 percent farm-raised genes exhibit behaviors that negatively impact migration, nesting, and survival. Basically, crossover with farm-raised mallards is diluting the wild gene pool and potentially impacting how many greenheads you see and kill each fall. Here are a few key points waterfowl hunters should be aware of surrounding the game-farm mallard conversation:

An increasing number of Atlantic Flyway mallards show some sort of farm-raised DNA

Farm-raised mallard genetics originate from old world European mallard genes

A study in 2023 found that less than 5 percent of mallards sampled in the Atlantic flyway were fully wild

Farm-raised genetics are potentially contributing to Atlantic flyway hunters seeing and killing fewer greenheads

Game-farm mallards take in food at about 50 percent of the rate that wild birds do

For every wild hen, it takes 3.3 game-farm or hybrid hens to produce the same number of ducklings

Mallards over the 30 percent farm-raised DNA threshold are showing poor migration habits

The duckDNA Program

There’s a way to find out if the mallards you’re hunting have any trace of farm-raised genetics. In 2023, Ducks Unlimited launched a potentially groundbreaking program that serves almost as ancestry.com for ducks. Through tissue sampling, biologists can determine the genetic makeup of a bird. This means that the results can determine if a mallard is 100 percent wild or some sort of hybrid.

While the sole purpose of the program isn’t just to study farm genetics, duckDNA focuses on samples from the mallard family. This includes black ducks, Mexican ducks, mottled ducks, mallards, and any sort of hybrid. Ducks Unlimited allows hunters to apply for the program before and during the season. This past year, DU enrolled over 600 hunters for free. Knowing that I was researching this topic, Ducks Unlimited offered to send me a kit which I used to submit the mallard I killed in New York for testing.

The Submission Process

I cut off a small piece of my bird’s tongue, placed it in the included vial, and secured it in the test kit before mailing it out. The instructions are super simple. Besides providing a tissue sample, I had to register with duckDNA, submit a few photos of the duck, and answer a couple of simple questions. I received my results 11 weeks after submitting the sample.

Mallard DNA Results

In mid-January, I received an email with the subject line, “Your duckDNA results are in!” The results were displayed in a pedigree certificate (see above) that shows the species breakdown, generation, and maternal lineage. The drake I shot was a hybrid between a farm-mallard and a wild mallard. This mallard’s genetic makeup consisted of 71 percent wild genes and 29 percent farm-raised genes—right on the threshold of where birds stop behaving as wild mallards.

That means there’s a good chance this bird exhibited traits found in farm-raised mallards, like poor migration. This drake, along with the hen it was with, were the only two mallards I saw the entire morning of my hunt. It is more likely that this mallard didn't migrate, but it is impossible to know for sure.

When I picked the mallard up, I noticed that even though the bird was fully plummed, it didn’t have a well-defined white neck collar. It also featured very light-gray plumage. Much lighter than the mallards I’m used to killing in my home state of Colorado. The head of this bird was also abnormally big.

The pedigree certificate labels the greenhead’s maternal lineage as “mallard-like duck old world,” meaning this bird can be linked back to European descent—the source of farm-raised mallard genetics. European mallards started being released in the U.S. nearly a century ago, and these genes slowly crept into the North American wild gene pool. Killing a mallard with a significant percentage of old world genes in the Atlantic Flyway is nothing special. Many of the greenheads eastern hunters harvest aren’t fully wild birds. They are similar to the mallard I killed on opening day—a cross between a farm mallard and a wild greenhead.

While my mallard’s genetic history isn’t anything groundbreaking or even surprising, it does add one more data point for researchers. Plus, it was fun to go through the submission process and wait to learn about the bird’s ancestry. In a way, it was like shooting a band but having to wait three months to learn where it came from.

There is still much research to be done to fully understand the impact of farm-raised mallard genetics. But right now, studies suggest that these genes are bad for ducks and duck hunting. And these poor genetics might be impacting how many mallards you see and kill each season. You can gain even better insight into mallards you hunt by applying to duckDNA next season. If selected, you'll have the opportunity to see what genetics are in your area and contribute to a nationwide waterfowl DNA study. Plus, you get a cool certificate to show your hunting buddies at camp.