The Hard-Earned Bear

Hunt big-timber bears without bait or hounds

Something had changed. After 40 minutes of still-hunting through silent timber, the woods erupted in chatter. As I neared a creekside oak flat, chipmunks barked alarms. Blue jays and crows screeched. A heavy branch snapped ahead, and I could see the top of an old oak swaying. But there wasn’t a breath of wind. As I took a knee, a bear swung around the trunk and walked along a stout limb, 30 feet up, perfectly broadside, and less than 40 yards away.

All across the Northeast, there are camps of diehard bear hunters for whom the September opener is as anticipated and sacred as any whitetail season. Watching baits in Maine or running hounds in Vermont or New Hampshire are high-odds options, but nearly half of the states in the Northeast force you to hunt bears the hardest way. Some Northeastern hunters say it’s impossible to target and kill black bears by still-hunting the big woods, but that’s just not true. Not nearly. Every September, all across New England, New York, and Pennsylvania, hunters in wool coats walk into the wilderness—and come out with bears.

My first year in our New York camp, five hunters spotted 12 bears in three days. A first-time bear hunter arrowed a young boar on an oak flat just three hours into the season. Luck? Maybe. But a few days later, another buddy shot a good one after finding an obvious bear trail along a swamp. Each year our success only improves. There’s a learning curve, but if you can still-hunt whitetails, you can do the same for bears.

The key is finding prime habitat. Bears need water, food, and dense timber for denning, preferably all within 50 acres or so. They’ll travel for one of the three, but like us they prefer a lazy existence. We start our scouting looking for the food. Black bears are obvious and destructive eaters. In the Northeast, they hammer beechnuts, acorns, and wild berries. If there is ag land nearby, they’ll leave the woods for corn. In a hot field, they’ll wreak such havoc that some farmers will beg you to hunt, and you won’t have to guess where to set up.

In the woods, where we like to hunt, beechnuts are a favorite forage. In a good mast year, scouting bears amounts to finding the best beech stands. Acorns are a distant second. In both cases, bears will climb the tree’s trunk, snap off branches, and then eat the nuts like a person working an ear of corn. As they discard the branches, a “bear nest” forms in the canopy. They’re easy to spot—a high-up jumble of broken branches, like a bird’s nest but sized for pterodactyls.

Bear sign around berry patches isn’t as obvious. We rarely venture into a tangle of dogwood or honeysuckle, but we scout the edges, looking for sign. Tracks and trails are easy to spot, especially after a rain, and any pad measuring wider than 6 inches tells you there’s a great bear nearby.

Scat is a foolproof way to determine what a bear is eating, and when. Break the stuff apart with a stick. You’ll see little seeds if they’re on berries, partial kernels if they’re on corn, or a smooth khaki coloration, like soft-serve coffee ice cream, if they’re on nuts. Bear scat oxidizes quickly from the outside in, so you can determine a rough timeline based on color too. If it’s an even oily green or tan, it’s very fresh. If there’s only a black crust, it was probably laid within 24 hours. If it’s black straight through, it’s fully oxidized and several days old. Several small piles with a big plop nearby indicates a sow with cubs. Isolated logs as fat around as a soda can probably indicates a shooter.

If you’ve done your scouting, it’s not hard to figure out a plan of attack for the opener. We set up on a trail or crossing just off the hottest food at first and last light. During the day, we move fast between the best areas, and super-slow once we arrive at them, always into the wind. Power lines, logging roads, abandoned rail lines, and old clear-cuts all make good spots to wait out bears. They favor low areas, like a saddle in a ridgeline or a dip in a logging road. Bears tend to walk along waterlines too, skirting the edge of a swamp, river, or creek. Last year I sat a clearing along a swamp edge on the north side of a berry patch. A bear came through at last light, and I took him with a .308 at 33 yards.

Don’t forget the wind. Bears can smell as well as or better than deer. Anything less than a perfect wind, and you won’t see a thing. You need to watch and glass very carefully too. With their paws insulated against sound, bears can move in near-total silence. But like I found out two years ago, they make an awful racket in a tree.

I watched through my riflescope as that bear walked the limb. His heavy steps swayed the whole canopy. I shook pretty bad too—but still managed to tag my first still-hunt bruin. No matter how long you hunt bears, you never truly expect to see one, especially at ground level. It’s always a surprise, and one that rattles the nervous system in a way only big predators can. That’s what keeps me going back each year to our New York bear camp for the September opener—my favorite opening day of the year. —Michael R. Shea

Walk the Grouse Road

“Guys get pumped to hunt the grouse opener, but they forget it’s still warm enough to go swimming,” says Maine guide Randy Flannery with Wilderness Escape Outfitters. “They hit the open popple -and-birch flats. But the birds aren’t in that classic upland cover in numbers yet because it’s too sunny and warm there.”

Instead, grouse find shade where aspens, spruces, and firs grow together. “One of my favorite hunts now is to walk the old skidder roads that run through the mixed growth, especially in the cooler air near water.” The birds hit the roads to pick grit in the morning and stay close for hours. Flannery puts one hunter on the lane and another 40 yards in the woods, then he and a dog swing wide in loops. “If the dog goes on point, I’ll call the closer hunter in for the shot. If I have a flushing dog, I push birds toward both of them.” The tactic works great without a dog too.

“We shoot lots of grouse this way. But even if we only get a few shots, it’s a nice walk in the shade.” —D.H.

How to Hunt Resident Canada Geese in September

The September resident goose opener is hot stuff in the East. “Here in Virginia, it’s almost as big as the dove opener,” says Avery pro staffer Lawrence Mauck. And it’s your best chance to pattern and bag a bunch of big honkers. “A couple of guys might take 15 or more on that first morning.”

With temps typically as sizzling as the gunning, Mauck likes to stay cool by setting up on a river sandbar. “These geese have been unpressured all year, and they’re still in family groups, with plenty of young birds that have never been hunted. So you can get away with throwing something a little different at them.”

Just like you, geese want to beat the heat, Mauck says. “They fly off the roost early and feed quickly—or even skip the morning feed altogether and go straight to water to loaf and stay cool.”

Like most summer waterways, the James River, where Mauck hunts, is loaded with boat traffic. “You have recreational boaters pulling up on the same sandbars and islands that the geese use, and the birds are totally unfazed by it.”

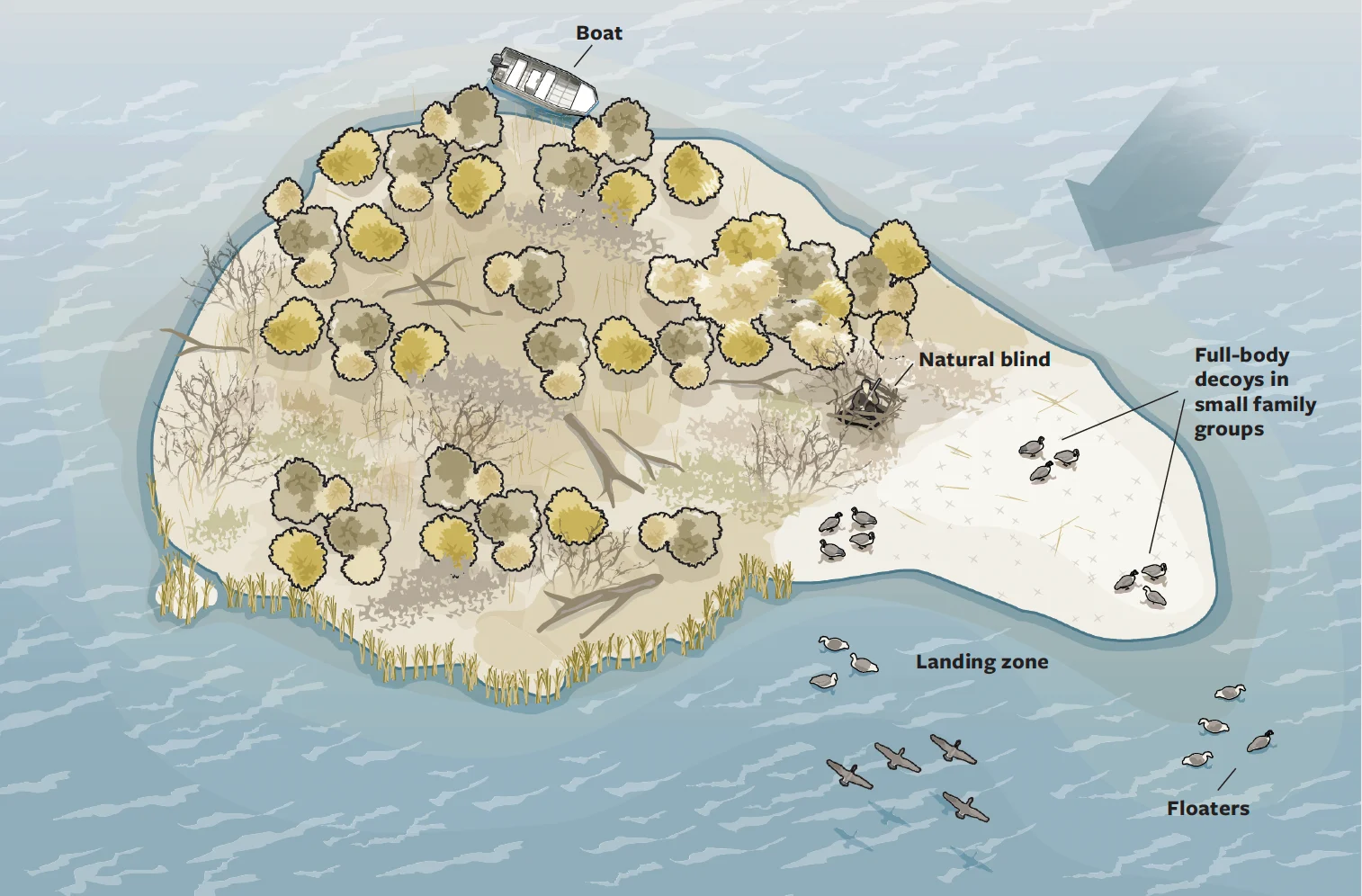

So that’s where Mauck digs in on the opener. He scouts the day before to make sure geese are hitting a given sandbar or island, then he sets up early in the morning with only 15 or so decoys arranged in small family groups of three, four, or five. “I’ll put out a couple pods of full bodies on the sand or in very shallow water, and a couple pods of floaters. I mix in loafers and sleepers, so they look as relaxed as possible.”

During the regular season, Mauck stashes his boat far off and fusses to make it invisible. “On the September opener, I can put it closer and just tuck it in as best I can.” Sometimes he’ll put a layout blind on the sand, but there’s usually plenty of vegetation for a natural blind. “I wear shorts and a camo shirt. I don’t need waders.” That’s because when dawn breaks and Mauck starts dropping birds in the floating decoys, he cools off with a swim. —D.H.

Spot and Stalk Squirrels Like Big Game

I saw the green leaves rustle and spotted an arc of long, fine hairs through my binos. “Stay right behind me,” I said. We slipped to the back side of a huge oak, and when we peered around the side, there he was, sitting on a burl and close. Jackson shot—and the Nerf dart bounced off the tree as the squirrel turned itself inside out getting away.

My son’s not old enough to carry a real gun in New York yet. But my real .410 worked fine, and we had a blast that day. The opener is perfect for bringing a kid squirrel hunting because all that foliage means you don’t have to sit and wait—which is boring for a kid. Instead, you have enough cover to go after them. Bring good glass, and give the hunt all the drama of a big-game spot-and-stalk.

Most squirrel openers in the East start far enough ahead of bow deer season that you needn’t worry much about the disturbance. Just avoid bedding areas. If you’re worried, use subsonic .22s. Or make it easy for the kid—hand him a shotgun, let him shoot, and the deer be damned. —D.H.

Opening Day Tradition: Watch Party

A week out from New York’s Northern Zone duck opener, my buddy called. “My dad’s going to make you watch Jeremiah Johnson,” he said. I wasn’t opposed—far from it—but I wondered why. “What can I tell you? He’s got this rule that anyone new to duck camp has to watch it before they can hunt.” As I walked up the porch steps, my buddy’s dad swung the screen door open wide. He looked like Bear Claw Chris Lapp crossed with a Son of Anarchy—big white beard, big white belly, hair that hadn’t seen scissors in years, plus a Harley Davidson do-rag and navy-blue suspenders.

“You’ve come far, pilgrim,” he said.

“Feels like far,” I said.

He smiled large as hell, then shook my hand. We’d get along just fine. All these years later, we still do. I’ve hunted with my buddy’s dad more than I have with my buddy at this point. We’ve chased elk out West, as well as deer, bears, and all manner of ducks and geese in New York and New England. Every opening-day eve starts the same way, on some ratty old camp couch. We ride due west till the sun sets, then turn left at the Rocky Mountains. —M.R.S.