AT THE PLACE where I hunt geese, children ski to school in winter. It is far enough north that a silver moon hangs over the shoulder of the hill at that hour, and the houses by the side of the lake, with lights turned on in their kitchens, glitter like a cluster of fallen stars.

Several mornings a year, from the vantage of a sand spit a half mile away, I watch this tiny community come to life. Even at that distance, I can see the figures of mothers bending over their children in the yellow gauze of porch lights, and through my binoculars, I am able to tell, by the shuffle of the tiny figures toward the county road, those who are skiing from those who go on foot. A train whistles on the Hi-Line, and soon the cones of light from the school bus rise over the hill. The bus driver stacks the skis on a rack above the back bumper. He ushers the knot of children aboard, and in a moment, the high beams search across the sagebrush flats toward the town of Sulfur Springs 45 miles away.

“The Christmas of Tristan McGill” was first published in the December 1991 issue. (Photo: Field & Stream)

As the bus lights begin to fade, one by one the lights on the porches are also extinguished. The men who work at the talc mine on the Missouri River will not be due at their shifts for two hours. The women who had stood at their windows draw their robes against the cold, and the community pulls softly back toward sleep even while the sky to the east starts to pearl.

For the hunter this is a time of magic. Geese that had sought safety on the expanse of the lake, sleeping on gravel bars where tributary creeks opened meanders of water through the ice, lift their heads off their feathers and rise with raucous honks. They draw wedges against the sky, heading toward fields of wheat and stubble corn to feed. I watch them with a damped heartbeat, for experience has taught me that neither my floating decoys, nor any attempt to call, will bring them to my shotgun barrel. If any geese fly to the finger of water by my sandbar, they will arrive in pairs or by fours, starting small in the low window of my horizon and then floating in, tilting their wings and expanding like black balloons to land at the edge of the spread.

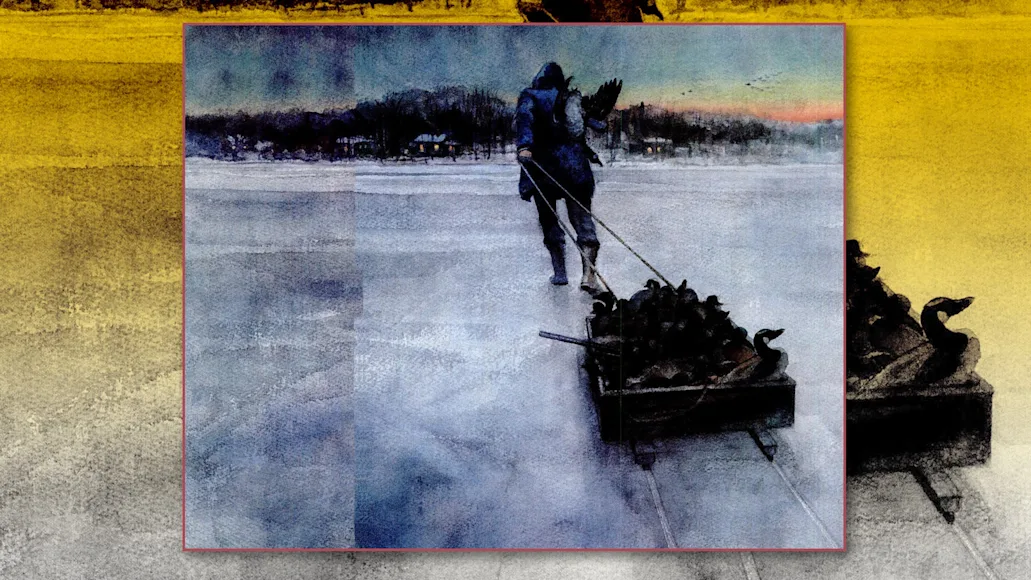

I am here to feel the spirit lift out of my body at the sight of that, but I am also here for a goose dinner. Christmas is two days away now. If I don’t drop a bird out of the sky, I will bag a turkey at the Safeway on the drive back home. I have held out about as long as I can, visiting this place twice in the past week, painting myself back among the brush strokes of the antique calendar art that this scene resembles.

There is one other man on the lake in the dawn and he, far more than myself, is the natural focus of this picture. For he is old—85, his granddaughter told me—with thin white hair falling in thin ringlets to his shoulders and a beard down to his chest. When I first came here a decade ago, he ice skated at this hour, his head bowed and his hands behind his back. His hair was shorter then. But a stroke took the certainty out of his legs—and made the left side of his face alternately taut and trembling—so that he no longer trusts himself on the blades. Now he brings a lantern to a hole in the ice and dangles maggots on silver hooks for perch. He is out here now, silhouetted in the glow. His granddaughter, whom I have not seen for several years, made our introduction. I’d driven to the lake because I heard the duck hunting was good, but being unable to find access near the community, I had taken a gravel road out along the shore and stopped at the first ranch house, situated on a point at the mouth of a cove. A young woman was pulling out of the drive in a pickup, and we both rolled down our windows with the engines running.

“I’m looking for a place to park so I can hunt ducks on the lake,” I told her.

She smiled at me, and the country-woman lines ran from the corners of her eyes into her temples. She asked me if I had a dog. No, I said, I just want to hike across the bay and lie down behind some log and shiver awhile.

“That’s okay then, you can park here. But we better let Tristan know.” She climbed out of the cab. “This used to be our ranch, but it’s just about all sold off now but the house. I’m Elizabeth McGill.” I introduced myself and she took the hand I extended, and held it longer than she might have. She looked at me a moment with her head tilted to one side. She was a beautiful woman, somewhere in her thirties, and made a startling picture when she stood next to her grandfather a minute later. Both had the same square jaw and glittering eyes. She hooked her arm in his and her chestnut hair mingled with the snowy strands that fell from his head.

“Doesn’t he look just like my old boyfriend Bill?” the woman said.

The old man peered at me quite closely. “Naw,” he said. “This one ain’t as good-looking.” He winked at me out of the eye his granddaughter couldn’t see.

Tristan McGill was Ireland-born and he had been raised in Norway. But he had lived along the breaks of the Missouri, on one ranch or another, when government trappers still hunted wolves on the sheep ranges. He said, “So you’re going to bring me a goose, are you?” and beckoned me to follow him into a back room off the hall that smelled like tobacco smoke and was cluttered with switches, tracks, and model train cars, in varying states of dismantle. “All I’m interested in is H-O. I was a brakeman on the Northern Pacific. We had cow ‘ketchers’ like this on the locomotive.” He turned an exquisitely detailed steam engine with coal car over in his bony fingers and handed it to me. “I make all the locomotives myself out of block brass. Sit yourself down,” he said. I didn’t go hunting that day until the sun was closing on the horizon.

I’d like to say that we became friends. He gave me a glimpse of what life had been like in Montana before fences, when cattle were free-range and ate through winter on hay stacked by beaverslide hay derricks. I, in return, provided him company. The granddaughter I saw little of in ensuing years. Shortly after we met she married into a family that held irritated land in the lee of the Little Belts outside Great Falls, and was busy there, no doubt. I worried about the old man but was starting a family myself, so my own visits were limited to the three or four days I hunted ducks every winter. I’d watch the gleam of his skates in the sunlight from the sand spit, and when the day died, I’d tie my ducks on a shoestring and trudge across the ice to the house, the front of my coat frozen from crawling over slush ice after birds that touched down out of range.

Slowing Down

“You gotta be crazy,” Tristan would mutter when I knocked at the door, and he would invite me inside for a cup of that stained hot water old ranchers pass off as coffee. “In the summer of ’37 we had just a terrible fire,” he’d begin, and I would be drawn back to his time, just as, during our visits after his stroke, I would attempt to bring him forward into mine.

The change came three years ago. Elizabeth had the door. She put a finger to her lips and ushered me back outside. “He’s not the same,” she said, “and he might not know who you are. God has given him good years.” Her voice caught. She took a deep breath and lifted the corners of her mouth in a wan smile. Later, she wrote her phone number for me on a piece of envelope. I was to call if I thought she ought to know anything. The doctor told her Tristan was in good health as could be expected and could still take care of himself. He wouldn’t come to the ranch, although she expected that to change. She was going to put the place up for sale.

But the sign never went up and the only thing that really changed during the last couple of years had been Tristan. Although be seemed happy enough to see me, his eyes wandered when I spoke. He became more and more withdrawn. There were days when he was himself. But sometimes when I knocked on his door, I could see him sitting at the kitchen table, with nothing on the Formica in front of him but a cup of cold coffee. It seemed to take him half a minute to come back from wherever his mind had transported him. When he opened the door, I would notice the smell of perch in the bucket in the sink. A film of dust covered the brass locomotives in his train room.

Strange as it may appear to outsiders, it never struck me as sad that he was alone, or particularly odd that his granddaughter would rely on me, who saw him only a handful of days during the winter, to help keep tabs on his condition. It is a lonely life up on the Hi-Line. You may drive 40 miles between ranch gates, and behind the squares of light in the distant windows, self-reliant men with thick hands and skinny arms pour themselves cup after cup of that weak old coffee before turning out the lights and lying down alone.

Then one Saturday earlier this December something had happened to change the way I looked at Tristan McGill. It was my first visit to the lake in a year. Sometime around noon, I picked up my binoculars to search out the old man among the scattered ice fishermen on the bay, and was heartened to find him at the center of a cluster of bundled children. Covering my shotgun with cattail stalks from the marsh, I hiked across the bay to say hello.

“Go along now,” he said to the boys when I approached. They were three boys, around eight years old. One of them screwed up his face and said, “Aww, now, do it one more time.” I watched Tristan dip his hand into the bucket at the side of his hole. He dug around a few seconds. Then he brought up the yellow eye of a perch on his thumbnail. He lifted his hand to his lips, and I watched his Adams apple work in his wrinkled throat.

“Go along now,” he said again, as the faces of the boys went into exaggerated contortions. He looked around at me.

“I eat all my bait,” he said. He tried to wink at me, and the left side of his face tightened and trembled, and his hair flew in the wind, and he looked quite mad.

Poor fellow, I thought. Poor old man. You see, by this time I had ceased to associate him with a name. I was acquiring the perspective you need to regard someone only as a character. It was simply a matter of creating distance. It was easier that way. I understood this as I watched the spasm in his face subside, and felt a sudden shame.

“That tow-headed boy is Old Doc Barrow’s. He’s the veterinarian, treated the horses for years.” Tristan lifted the corners of his mouth where his mustache was yellowed from sixty winters of pipe tobacco. “My wife and I too for that matter.” He dug another fish eye out and slipped it on his silver hook. “They’re good boys. And the eyes don’t taste so bad, you know.”

It was as much speech as I’d heard from him in a long time. And when he lowered the line into the hole it was as though the last few years sank with it. He had not possessed such a casual certainty about himself, nor offered such candid reflection since before his stroke. “Sit yourself down.” He gestured toward his thermos. “Pour a cup.” He glanced at my coat, the pocket flaps stuck out like wings where they had frozen. “You must be just about the craziest boy I met.”

So I had sat myself down beside the old man’s perch fishing hole, realizing that I knew little more about him than I did about life underneath the ice. Tristan said something then that at the time seemed very curious. “Elizabeth wants me to get my cataracts removed. I see rings around the moon that aren’t supposed to be there. Do you see rings around the moon? There’re red and blue ones. They’re very beautiful.” I shook my head. “No,” he went on, “I don’t suppose you do. At first, I didn’t like seeing them. But now I sort of like things the way they are.”

I didn’t know what to say to that, and when the moment for a response passed, we lapsed into silence, both of us watching the flame-orange tip of his rod for the slightest movement.

Family Meal

Now, on the day before the night before Christmas, I watch Tristan fishing through my binoculars, and wonder what is going through his mind. I’ve settled it in my own head that he must have been talking about some kind of acceptance that day. I don’t know what it’s like to get old and drift away from the Earth the way Tristan’s been doing the past years. It seems like he goes away and comes back, goes away and comes back. Is he visiting the past or seeing into the distance as a form of preparation for the time when he won’t come back? I really don’t know.

He is sitting there by his hole with his lantern throwing a faint glow in dawn’s light when the geese come in. Their wings cup and their big feet are reaching down, and then I feel it rise in me. It is like a great breath of air coming in, and when it goes out I am rising to my knees but the ice is no longer under me. Boom! The geese veer off but one catches as though coming to the end of a rope and it tumbles, end over end. It comes down with one wing stuck out and smashes into the water. Feathers drift down in its wake. They blow away across the ice in the pulses of the wind, the way the shot echoes away, and once more the lake is framed in northern silence. I retrieve the goose. Heavy-bodied, its feet drag when I lift it by the neck.

“Christmas dinner,” I say to Tristan later that afternoon. He looks up from his hole and nods his head. “Your wife will be pleased.” We exchange just a few words. Now that I want to reach out toward him I can find nothing to say. Another time, maybe. It’s getting late and I have a long way to drive.

“You take care now,” I say, and trudge on down the bay with the goose hanging from a shoelace over my shoulder and my sleds of decoys scraping across the ice. When I stop to rest, steam lifts from the front of my wool shirt. I can see the school bus pulling up the county road, and in this country of thin air and frozen water, the laughter of the children sings to me from a quarter mile. Already lights are turning on in the houses. I turn toward the light from Tristan’s porch that burns all day. Once more I am reminded of a cluster of stars, this one merely distant from the rest. I begin to walk very quickly. I know what I’ll do before my sleds touch the shore.

“Well, hello.” Tristan stands in his doorway. His eyes are having a hard time focusing on me. His hair is all matted and he is wearing a long underwear top that clings to his bony chest and makes him look old. I can smell the woodsmoke and feel my heart sinking. Maybe this is all wrong.

“I didn’t forget anything,” I say quickly. “I just remembered when I passed that store in town that I never did get you that goose dinner I promised. So I stopped and picked up some beer and sauerkraut. This is a young bird and he ought to simmer down pretty tender in an hour or two if that’s not too late.”

Tristan nods his head. “Well, you come in then,” he says. “Come in and we’ll just get these perch all filleted and laid on ice before that bird of yours is done cooking. I never had a goose done in sauerkraut.”

But I stand there, still a little awkward, trying to make up for lost time. I say I’ve been meaning to get him a goose for years, but before there were lots of ducks and no geese, and only now there’re lots of geese and no ducks. It’s kind of ironic, I tell him. Yes, he says, there’re more geese now than since he was a young man.

“You’re sure it’s not too late?” I ask him.

Tristan scratches his head. “Just been near ten years is all.” Then he realizes I mean too late in the day and he says, “Oh, for Christ sakes,” and ushers me in the door.

I remind myself to buy a turkey on the drive back home.