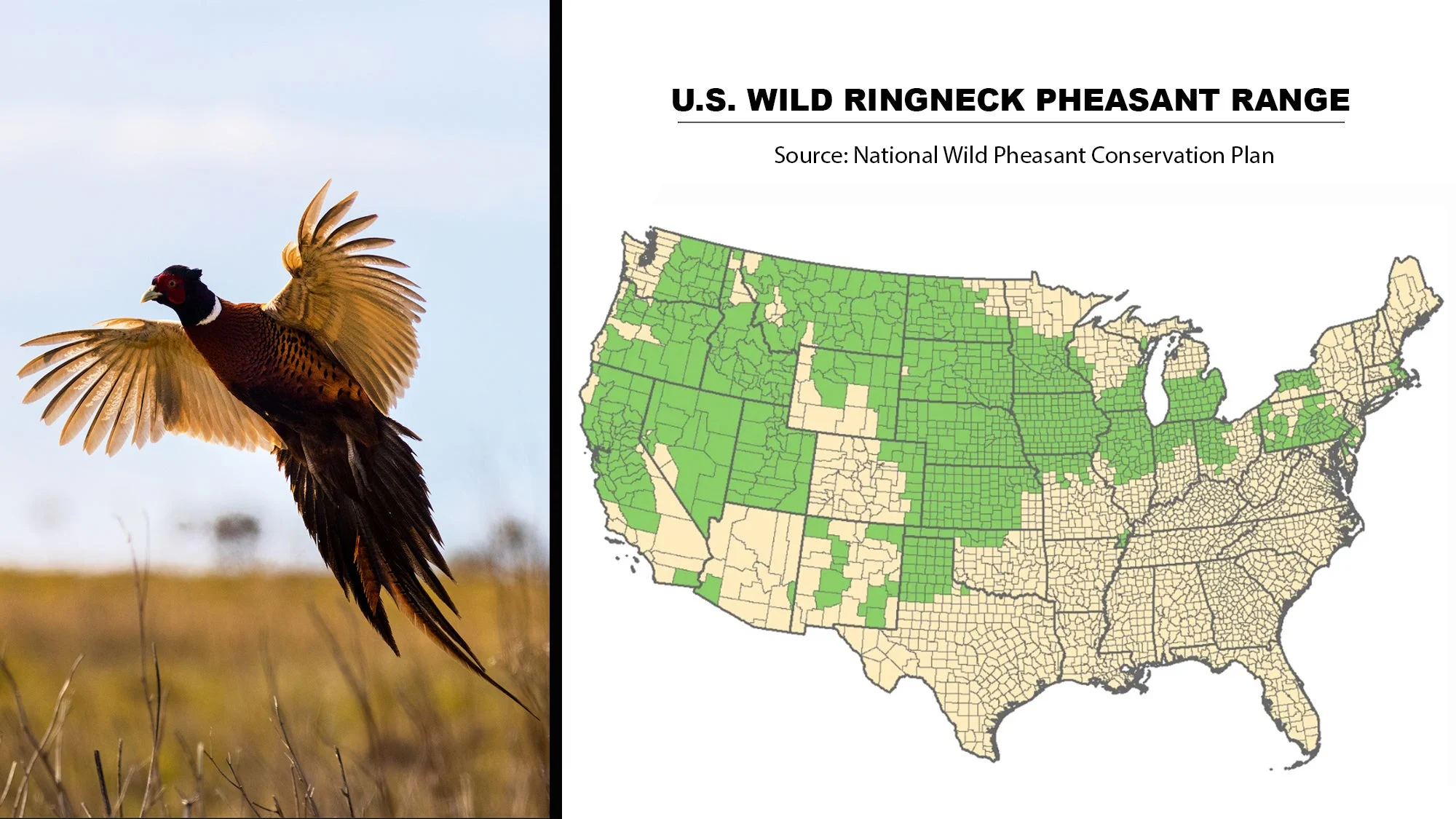

A colorful, raucous invasive species made good, the ringnecked pheasant is our most successful wildlife import. Brought to Oregon from China in 1881, the pheasant spread from coast to coast. It became a common sight and a popular game bird through all but the southeastern states. Pheasant hunting reached its peak in America in the years following World War II, but in the latter half of the 20th century, changes in land use, primarily intensive agriculture and forest re-growth, has reduced their numbers and their habitat. The core of the ringneck pheasant’s U.S. range

remains the Dakotas, Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas, though it is still found in many other states, as well, and is still a favorite of upland bird hunters almost anywhere you find them.

Ringneck Pheasant Range, Habitat, and Appearance

This map shows the current range of wild ringneck pheasants in the U.S., according to the The National Wild Pheasant Conservation Plan, Second Edition, published in 2021. Adobe Stock and from The National Wild Pheasant Conservation Plan

The rooster pheasant’s green head, red cheeks and white neck ring at the one end, and its long, brown and black-barred tailfeathers at the other, give it an unmistakable appearance. A coat of iridescent feathers covers the rest of bird, and its gaudy coat helps it attract females in the spring. The hen, in contrast, is a light brown all over, to better hide from predators. Pheasants are large birds, with the roosters weighing up to 3 pounds. As for vocalizations, hen pheasants are mostly quiet, although they will make soft clucks to communicate with other birds and their young. Rooster cackle to attract hens, mark territories, and to sound the alarm when they flush.

Hen pheasants are drab compared to the gaudy roosters, but they are beautiful birds in their own right. WildMedia / Adobe Stock

One of many pheasants in the world, ringnecks have adapted to live in grasslands. Judge Owen Denny, the diplomat who first imported pheasants to America, noticed that they lived in the open country around Shanghai, and thought they might do well in grassland areas of the Willamette Valley. Denny was correct. Pheasants thrive in grasslands, and around the edges of grain fields in farm country. They like wetlands for winter cover and some brushy overstory. Pheasants roost on the ground and don’t do well near tall trees that can provide perches for avian predators. Given enough thermal cover in cattails or heavy grasses, pheasants can survive severe cold as long as deep snow or ice doesn’t bury grains and seeds they rely on for food too deeply.

Once Denny’s shipment of birds took hold, pheasants spread, both on their own and via stocking, until they were widespread from coast to coast, with only the southeastern states proving inhospitable. The story goes that Iowa’s population was established in one fell swoop in 1900, when high winds blew down a game-farm fence, freeing 2,000 pheasants near Cedar Falls.

Ringneck Pheasant Life History

Male pheasants fight, establish territories, and display in the spring to attract mates. One rooster pheasant can breed several hens, and the birds do not form pair bonds. Hens scratch a depression in the ground and lay clutches of a dozen or so eggs. Pheasants will re-nest, sometimes up to three times, if their eggs are destroyed by flood or mowing before they hatch. Chicks can fly at just 12 days of age. They will remain with their mothers for up to 80 days.

In very cold weather, pheasants can actually slow their metabolisms and survive for several days without food. With the coming of spring, winter flocks break up as males establish territories and attract hens.

Feeding Habits

Pheasants rely heavily on waste grain in corn fields, especially when weather turns cold. F&J McGinn / Adobe Stock

Pheasants eat insects, weed seeds, corn, soybeans, and other crops, relying especially on corn in cold weather as high-energy food. Chicks feed almost entirely on insects when they are young, and that high-protein diet helps them grown quickly.

Predators and Threats

Foxes are particularly adept and catching and killing pheasants. PetrDolejsek / Adobe Stock

Raccoons and skunks eat pheasant eggs, while a foxes and, to a lesser extent, coyotes, prey on pheasants, as do hawks and owls. However, none of those predators are nearly as much of a threat to pheasants as the habitat destruction that is a part of modern agriculture as more land is cleared to make bigger farm fields. The clearing of fencerows, marshes, and grassy areas kills pheasants much more efficiently than any predator can. Pheasants need undisturbed grass fields to nest and raise broods, and in the winter they require heavier cover like tall prairie grasses or wetland areas to stay out of the wind.

While hunters do take many pheasants during open hunting seasons, only male pheasants, which are easy to distinguish from hens, are legal game. Since one male bird can breed many hens, hunting rarely harms pheasant populations. It does no good to stop hunting to “rebuild” populations, since relatively few pheasants survive more than a year in the wild, whether they are hunted or not.

Ringneck Pheasant Conservation

Pheasants are far from threatened, but populations decrease every year as available habitat disappears under the plow. High commodity prices and large-scale farming operations mean more land goes into production every year, leaving no room for pheasants or many other grassland species. Pheasants Forever

is the main conservation organization devoted to preserving pheasant habitat. Government programs like the Conservation Reserve Program pay landowners to idle cropland acres and plant them in wildlife habitat, which often benefits pheasants and many others species, including pollinators, while also reducing soil erosion and improving water quality.

Ringneck Pheasant Hunting

A hunter shoots at a crossing rooster. Adobe Photostock.

The imported ringneck pheasant remains America’s gamebird. Wary birds blessed with sensitive hearing, pheasants prefer to run or hide from danger rather than fly away from it. Therefore, pheasant hunting is largely a game of forcing birds into the air in gun range. Traditional pheasant hunts employ large gangs of hunters divided between blockers, who lined up at one end of a field, and drivers, who walk in a line toward them, pushing birds ahead. When the drivers reach the blockers, the air can fill with pheasants. While such group hunts are still popular in places, it’s much more common for smaller groups to follow dogs into the field. Dogs can force birds into the air, or seek out and point hiding birds until hunters get close enough for a shot.

On a given day, pheasants typically roost in heavy grasses, walk or fly to feed in grainfields in the morning, loaf in grassy cover near food, feed again in the afternoon, and roost in the evening. The best place to consistently find pheasants is in good grassy cover right along the edge of crop fields. In cold weather, the birds will move into heavy grasses or wetland areas to stay out of the elements.

Dogs are essential for finding downed pheasants. Tough birds, they can take a lot of shot and still fly off or bury themselves in heavy cover even when mortally hit. Despite their bright feather coats, they disappear in the grass when they want to. If a pheasant only suffers a broken wing, it will run from where it hit the ground, and only a dog will be able to track it down. Hunters with good dogs lose very few of the pheasants they shoot.

A pair of rooster pheasants taken by the author with a 12-gauge Blaser F16 over/under on a winter hunt. Phil Bourjaily

Most pheasants brought to bag are shot within 25 yards of the gun. Twelve-, 16- and 20-gauge guns make the best pheasant guns

, and an Improved Cylinder or IC/Modified combination is best for most hunting. Lead 4, 5, or 6 shot is most popular. Since some very good pheasant hunting takes place in areas where non-toxic shot is required, hunters might choose steel 2, 3, or 4 shot, or bismuth 4 or 5 shot.

The ringneck pheasant’s most famous relative is the chicken, which is the domestic version of another pheasant, the Ceylonese jungle fowl. Wild pheasants are also, therefore, excellent tablefare, more flavorful and much leaner than chicken, but not dissimilar in taste, and well worth the effort to hunt them.