By Potomac River standards, a 7-pound snakehead is just a baby, but that’s what my personal best from the summer of 2016 weighed. It also didn’t come from Maryland or Virginia. My uncontrollable obsession with the most hated invasive species on the East Coast started close to home on the Delaware River in New Jersey, a waterway that many people don’t even realize holds these fish. Instead of loathing their presence, I saw a unique opportunity to figure out a new species that, in many respects, I find more challenging, powerful, and fun than the local players I’ve chased since I was a kid. My goal for the summer of ’17 was to top my personal best snakehead, not only by fishing known hotspots but also by poring over Google Maps and chopping or rowing my way into any puddle or tributary where I thought I might find one. I caught my first snakehead on June 6 and missed my last on October 15. In between, I racked up 26 total, including an 8-pounder. What I learned by devoting an entire season to these fish might break some snakehead misconceptions, perhaps encourage you to join the growing legion of devout snake hunters from Queens to Miami, or inspire you to kick off a personal snake quest of your own, because the bottom line is, they’re not going away. Under Pressure Thanks to nearly two decades of media hype, many people believe snakeheads are dumb, ravenous eating machines that destroy any food source that gets in front of their faces. Not only is that false, I’d argue that snakeheads are smarter and more selective than most other fish. All fish are susceptible to pressure, but snakeheads are even more so in my experience. Fish an easy-access spot where lots of other anglers are throwing frogs, and you’ll skunk more often than score. You may also get half-hearted follows with no commitment. Snakehead fishing is most akin to muskie fishing; you’d better not lose focus or you’ll miss that one surprise hit you get after hours of nothing. This is why it pays to hunt down unpressured fish, and not only did I do this on foot, but I also leaned on a Flycraft to get me into far corners and backwaters not accessible to many anglers.

On the Move

Many people assume snakeheads spend most of their time lying in ambush, and if you catch one on a piece of structure, you’ve hit the only one there. Joe Cermele

The most snakeheads I caught in a single outing was seven in just two hours on a June afternoon. Interestingly, they all came off the same little cluster of lily pads in a very small backwater cove. Many people assume snakeheads spend most of their time lying in ambush, and if you catch one on a piece of structure, you’ve hit the only one there. My experience over the course of the summer proved otherwise; it’s highly unlikely that all seven fish were sitting together, but rather that they were out roaming and I would intercept a new fish every time one moved into that little cove looking for food. On another trip in July, after hours of pounding pads and duckweed-covered mats with no luck, I rowed onto a skinny mudflat with no vegetation. My friend Frank Heater and I spent the rest of the day sight-casting to snakeheads that were cruising in the open like bonefish. Both scenarios told me these fish can and will cover a lot of water in a day, and while they love veggies, they don’t stay in them 24/7.

Joe Cermele

Over the Top

Lures like spinnerbaits, chatterbaits, and soft-plastic swimbaits that work effectively through the slop, mats, weeds, and pads snakeheads love will get pulverized. Personally, I never throw any of them. The foreboding wake and toilet-flush take of a snakehead is the drug that pulls me away from smallmouths and trout in the summer, so if I can’t get them on top, I don’t want them at all. Every snakehead angler has his confidence lures, and mine are the River2Sea Spittin’ Wa

. The Wa is a hollow-body popping frog, and I’ve found that the cupped mouth moves more water with a slight twitch than traditional frogs do, which comes in handy when you’re being tracked by a noncommittal snakehead. The Ribbit is a soft-plastic buzzing toad introduced to me by a fellow snakehead freak in Florida. Rigged on Stanley’s Double Take hooks, when this lure gets blasted, connection percentages are significantly higher than with a hollow body. Both lures have a time and a place based on the amount and type of vegetation, but no matter which I’m using, I always throw black first. Always.

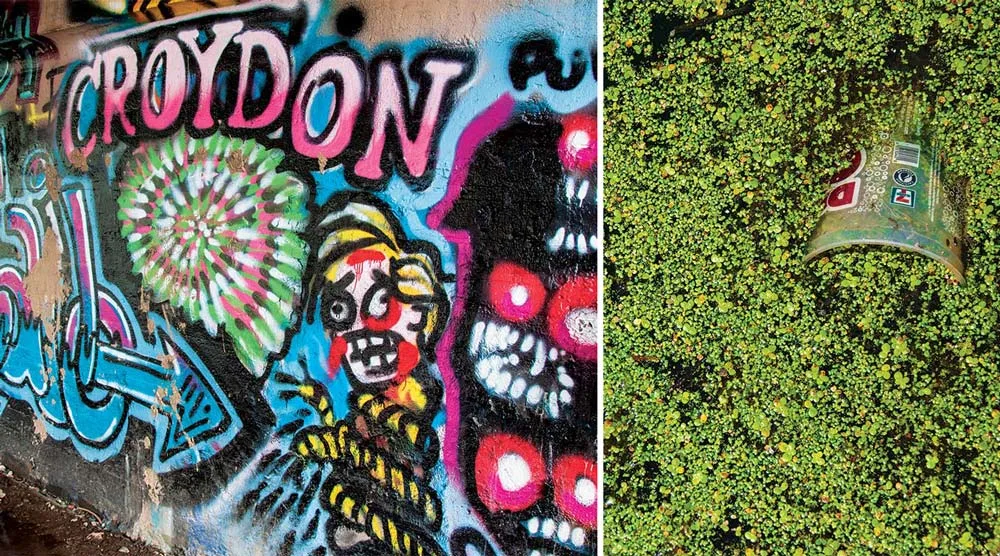

Greens, Graffiti, and Grease: Common sights of a snakehead quest. Joe Cermele

Power Pole

In the winter of 2017, I had a custom snakehead spinning rod built. The blank had enough power to battle a 50-pound striper, which got some head shakes from buddies when they saw the finished product. But it was exactly what I wanted. You don’t really need a heavy rod to fight a snakehead, but what rookie snakeheaders fail to consider is what you might have to pull that fish through or out of to land it. I commissioned the rod because I’d lost too many fish the previous summer trying to drag them through 20 feet of pads to the bank. I matched my “Snake Charmer” with an inshore saltwater reel spooled with 65-pound braid, and though I couldn’t cast a frog as far as I could with lighter tackle, I could throw it a lot farther in tight, brushy quarters than I could with a conventional frogging outfit. It was worth the money because that rod brought every fish it hooked to hand. The extra stiffness also drove frog hooks into rock-hard snakehead jaws effectively, and considering how brutally snakeheads fight, that heavier rod got plenty bent.

Skinny Genes

Snakeheads naturally prefer to live in shallow water, which makes narrowing down a Google Maps hunt for likely haunts easier. They are also not particular fans of strong current, and considering that the Delaware River and its larger tributaries have heavy flows, the next key to the search was finding shallow water that wasn’t moving—or that was moving very little. I explored everything from back eddies to creek mouths to tidal flats that fit the bill, and what I learned is that even a small pocket of skinny still water could hold a fish or two. If I discovered vegetation in these locations—milfoil in particular—I knew the chances of finding a snake in the area just jumped. Most important, I learned to never judge a spot by a single visit. Several times throughout the summer, a niche piece of snakey water that turned up nothing the first few times would magically kick out a fish or two on the third or fourth visit. It was a fifth visit to one of my Google spots that produced my 8-pounder in late August.

Baby Mama

Small Fry

A juvenile snakehead netted out of a passing fry ball in a New Jersey backwater.

Most of the time, connecting with a snakehead requires covering ground and making a lot of casts until you find a willing taker. The exception is if you spy a fry ball. Snakeheads can spawn in the Northeast from early June through late August, and the babies swim on the surface in a tight cluster that often appears red in color. It’s hard to miss a rippling, flickering fry ball, especially on a calm day, and where there’s fry, there is a mama snakehead. Females are undaunted protectors, and if you drop a frog in the playpen, mom will react. If you’re fishing a pressured area, that reaction might just be a nudge or a nibble; she knows the game, and getting her to strike aggressively can take time and patience, or enough casts to get her really pissed. If you find a far-flung fry ball that hasn’t been bombarded, that frog is usually sucked down before you ever engage the reel.

Cleared to Fly?

There are two questions I get about snakeheads more than any others. The first is, “Where did you catch that?” I hardly ever answer that one with any real details. The second is, “Did you get that on fly?” My usual answer to that is, “I wish.” To date, I’ve yet to stick a snakehead on a fly. While a snakehead will happily destroy a weedless popper or slider, you need the perfect scenario to make it happen. Most of the places I snakehead-fish on foot simply have no backcast room. In the ones that do, opting to flyfish blindly is severely handicapping your game because you’ll never cover as much water as you can firing a frog around on spinning or conventional gear. The recipe for success is being in a position where you’ve got room to wave a 9-weight and either see a fish to cast to or have a pretty good idea of exactly where one is sitting. I found myself in a few fly-friendly scenarios via the Flycraft in midsummer, but I didn’t have a fly rod. In early fall, however, I had just started to dial in a fly spot before the temperature dropped. During the last exploration of the season, my good friend Joe Demalderis stuck a 5-pounder on the long rod while I was on the oars. After switching positions, we didn’t move another snakehead the rest of the day.

Fight Dirty

It makes no difference if a snakehead plows a fly, sucks a frog, or bashes a buzzbait; there’s a good chance it will come unbuttoned no matter how solidly you think you jammed the hooks. Not only do these fish have hard mouths and lots of teeth, they also jump, spin, and twist wildly as they fight. Stout tackle comes into play here because you’ll up your landing rates if you keep the fight hard, fast, and dirty. Once a snakehead is pinned, the last thing you want to do is slack up or let that fish run. There’s zero finesse involved. My drags are cranked down to the max, and once I’m in, I want to keep that fish’s head coming toward me while applying heavy pressure. Rip that fish to the bank or the net, because if you give it even a second of control, the odds fall out of your favor. I can’t count how many times I’ve seen a lure fall right out of a landed fish’s mouth as soon as tension comes off the line.

Get Cooking

The deep-fried payoff from a good day. Joe Cermele

I think snakeheads are beautiful. The cobralike pattern on a young one is particularly brilliant. Other people think they’re the most hideous, monstrous-looking fish they’ve ever seen, making the thoughts of eating one gag-worthy. I get a laugh from this because a large part of the reason they exist here is that the Asian community smuggled them in as a food fish (the other reason is the black market aquarium trade). I grew up close to salt water, so I’m partial to flounder and sea bass. Freshwater fish just don’t excite me as much. Fried snakehead, on the other hand, makes my mouth water. I’d take it over the best piece of catfish or walleye any day. That’s the truth. Snakeheads might live in some mucky places, but they are not scavengers or bottom-feeders. Their flesh is some of the firmest, mildest, cleanest-tasting white-meat freshwater fish I’ve ever eaten, and I converted a lot of nonbelievers during my quest last summer.

Joe Cermele

Reality Check

It’s impossible to post a snakehead photo on social media without people dropping “kill ’em all” comments. What I’ve noticed is that a big percentage of these haters don’t live where snakeheads live, and they have absolutely no firsthand knowledge about how these fish interact and coexist with the species that were already established. They know only what they read, a lot of which is outdated information. In the last few years, there’s been somewhat of a relaxation in thinking among biologists, particularly those working at snakehead ground zero in Maryland and Virginia. Nearly 20 years ago, they believed snakeheads would wipe out all native fish. More than a decade and several studies later, it turns out that hasn’t been the case. Snakeheads in a small, cutoff body of water can have a major impact (and are also easier to eradicate), but in vast systems like the Potomac and Delaware drainages, it seems they have carved a nondestructive niche. In fact, I’ve yet to meet a bass angler from New Jersey to Florida who says they’ve noticed any negative impacts on largemouth or smallmouth populations since the flourishing of snakeheads in major waterways. These invasive fish may be fierce predators, but they’re not immune to predation. I have witnessed bass and crappies decimate schools of snakehead fry many times, which suggests checks and balances. In recent years, Virginia changed its rules to allow snakeheads to be released. Delaware has added them to its list of state-record qualifiers. Several snake-infested states that once mandated killing them now only suggest killing. There is no doubt that U.S. waters didn’t need snakeheads, but there is also no doubt that these highly adaptable fish are here to stay. And I suspect that many of the people who incessantly trash them are secretly afraid that if they ever gave snakehead fishing a shot, they might fall in love with it too.

Go Where Others Can’t

A big part of my summer snakehead success was a direct result of being able to access small bodies of water—or pieces of larger bodies of water—where the average guy couldn’t go, and to do that I used a two-man Flycraft. Flycraft

A big part of my summer snakehead success was a direct result of being able to access small bodies of water—or pieces of larger bodies of water—where the average guy couldn’t go, and to do that I used a two-man Flycraft

, which is a cross between a raft and a drift boat. The boat takes less than 20 minutes to assemble, it’s light enough for two guys to carry without breaking a sweat, and it’s tough enough that you can chuck it over a guardrail into a pond if you need to. Even with two big guys on board, I could paddle effortlessly in as little as 6 inches of water, and the elevated seating gives you a better vantage point than a kayak. I put a 50-pound-thrust Minn Kota Endura Max transom-mount trolling motor

on the back to range farther than oars alone would take me—and where it took me was to a lot of fish that ate faster than the ones swimming by the parking lot in the community hole. From accessing streams you’ve only ever explored on foot to ponds with no boat ramp, this investment has the ability to open up new possibilities on home waters. And unlike a kayak, a disassembled Flycraft will fit in the trunk of a Beetle.