Editor’s Note: All this week, we are asking F&S writers and editors to pick their favorite—okay, one of their favorite—stories from the Field & Stream archives. Below, F&S executive editor, Dave Hurteau, introduces a modern classic on an an all-too common and difficult topic.

When I was a young F&S assistant editor back in the 1990s, one of my jobs was to read unsolicited manuscripts sent in by readers. At the time, we had close to 2 million subscribers, and I’d say roughly half of them filed a story whenever one of their favorite hunting dogs walked its last trail. I read so many of these stories that I became completely immune to them.

I remember when one such story, this one written by a regular F&S contributor, went around the office for the editors to comment on. Everyone loved it. “Devastating!” “So good!” and “What a heartbreaker!” read the comments before mine. I wrote: “If I have to read another dead-dog story, I’m going to spit up.”

Fast-forward to 2020 when Hal Herring’s “Seasons With Bear” hit my desk for proofreading. Looking at the title, I thought, Oh boy, here we go_, and then I went about reading the piece as if it were a manual—knowing that no amount canine calamity or doggy despair could touch me._

A little more than three quarters of the way through, in one of the biggest surprises of my 30-year career at F&S, I had to push the story aside for a second—so I could have a good cry. —Dave Hurteau

Learn how to subscribe to the new Field & Stream magazine here!

Seasons with Bear

Every hunter who has ever trained and loved a dog has a story. If that dog lives to be old and gray-faced, stove-up from heroic efforts and mishaps afield, groaning on a bed by the woodstove, feet twitching in dreams of long-gone birds and battles and glory, that is one kind of story. If your dog dies, violently, needlessly, at the height of his powers, the sun-lit days of wind and prairie and swamp still unfolding, and then cut short, that is another kind of story, indeed.

Fall

In the early 1990s, with a carefully timed phone call at midnight, you could leave a message and be first in line to reserve a day on the Teller Wildlife Refuge, a 5-mile piece of bottomland along the east bank of Montana’s Bitterroot River. The Teller was thriving, a landscape conserved and more powerfully alive than ever—a patchwork of hayfields and other cropland, dense hedgerows of wild rose, chokecherry, and hawthorn rustling with pheasants, dark-water cattail marshes and ether-clear spring creeks snaking through, all of it easing only slightly downhill to the big cottonwood forest that shelters the braids and oxbows of the Bitterroot River itself.

My Labrador, Bear, was 13 months old. I remember him that day as a cannonball brush-buster—45 pounds, pure black, utterly fearless in the water. The Teller Refuge trip was Bear’s first hunt, and the first for me with a retriever that I’d trained. We were not set up at first light; I’d never been there and needed a little daylight to get the lay of the place. Bear bounded, came back, bounded, came back, walked to heel, serious, sober. I carried a pillowcase stuffed with four mallard decoys. We crossed open fields to a bend in a spring creek, where a patch of cattails offered the only cover. As I threw out the dekes, already there were the wild voices of Canadas that we could see in lines above the river. A flock of teal whirled, and mallards passed over fast, the jet noises of their bodies cutting cold air. Three drake mallards came in hard to the decoys, wings cupped, straight out of the northwest. I poleaxed the drake on the far right, leaned back, turned, and fired my second shot foolishly behind the other two. Then, adding more foolishness yet, I racked the slide and fired another round as they disappeared against the bottomland trees, too far away. Waterfowl hunting—and this is as true for me now as it was then—is so intense that I frequently have to stop and remind myself to settle, to enjoy, to still my raging pulse and blabbering, often cursing, mind.

Bear emerged from the water with the drake clamped in his jaws. His clear pale eyes locked on mine, and he walked up to my leg and sat down still holding the duck, looking out over the water. I took the bird from him, hugged him, let him shake beside me, and stopped him from grabbing the bird again before we tucked back into the cattails.

By 9 a.m., we were limited out—each bird a perfect retrieve. I picked up the decoys, and we took the ducks back to the truck, then went out to walk the spring creeks, jumping a few Wilson’s snipe, Bear working close, flushing them. He’d never seen them before, and for the two I killed, he retrieved them with a little less fervor than he had the drakes; they are so tiny and, like mourning doves, their feathers slip and stick to tongue and palate. I put them in my jacket pocket and we walked to the river as the day warmed and gray clouds gathered; autumn in the Bitterroots—the smell of apples from the orchards on every wind, big brown trout like bars of light bronze hovering over the sand and gravel in almost every little tributary of the river.

Winter

Back then, my wife and I were living on a mule ranch high on the east side of the valley in an old house with asbestos siding and bad plumbing. It had a collapsing woodstove that devoured lodgepole pine logs like a deity insatiable beyond any propitiation and that offered little heat in return. We took care of the mules in exchange for rent. Behind our home was another, more fallen house, occupied by a succession of squatters, adventurers, and families in transition. It is hard to describe how much of that there was at that time in the Bitterroots—Americans on the move from California and Georgia and points between, restlessly looking for a frontier.

One of those drifter families had come in with a litter of Lab puppies, stayed in the house through December while they sold as many as they could, and then took the cash and disappeared. They left one pup behind, in an old steel building on the ranch. I found him there, hidden behind some old buckets of hydraulic fluid. He’d rampaged the place, knocking over a full-size oxyacetylene rig, tearing up a blanket they’d left for him. His shyness—or more likely shock from being alone—lasted only a few minutes before he began wiggling and leaping at my pac boots. My wife and I invited him to our house for Christmas.

Midmornings that winter, Bear and I would walk across the place to an abandoned white barn. Shotgun in hand, I’d toss a rock onto the roof and listen as the pigeons startled from the rafters inside. I’d command Bear to heel, and then to sit. Within a few seconds, the pigeons would start hurtling from the ventilation door above us. If my shooting was good, the birds would fall downhill, into a coulee, and I’d release Bear for the retrieve. We did this several times a week. We were driven, intense, with few distractions. During his fourth and fifth months, we worked the pigeons or threw the dummy on the now-thawed sloughs along the river, or we went into the mountains to flush blue grouse.

Summer

Bear lived with me in my timber-thinning camps in the summer, and after perceiving the real danger of a man with a raging Husqvarna 262 felling tree after tree, each falling willy-nilly and with sometimes lethal force, Bear would disappear into the forest while I worked. Whenever the saw shut down for refueling, he immediately appeared, tail wagging, tongue lolling. We’d play fetch or wrestle, share a drink of water or a bite of deer jerky, then I’d go back to work. In the evening, as we hiked back to camp along my cutline, I’d find his beds, clawed out in the duff in the shade of spruce or piss fir as he’d followed me all day from a safe distance.

Once in your hunting life, if you have time, you should train a dog, become immersed in the psyche and soul of another animal for whom you are 100 percent responsible, and whose senses, and sense of the world, are so beyond your own that every moment, every day, is a process of revelation.

Fall

It is difficult, all these years later, to recall just how free we were, that dog and I. Children were not yet born, parents were still alive and well, and even the idea of paying for houses and acreage with steady jobs was as yet undreamed. September is the gold of a hunter’s year in Montana, the opening of upland bird seasons for grouse and Hungarian partridge, with sometimes enough doves and snipe around to vary the bag even more. Elk and deer are still weeks off, and pheasant, waterfowl, and antelope seasons don’t open until October. There is a glorious freedom in simply chasing birds. And Bear and I took every advantage of it.

Each trip to cut firewood in the Bitterroot National Forest included a few hours of hunting blue or ruffed grouse. I head-shot snowshoe hares, and Bear retrieved them with the same grace he did birds. We came home exhausted, loaded with firewood, bearing some of the finest game meat on this earth, and sat together on the porch to watch the sun fading over the mighty blue yawn of the Bitterroot Range.

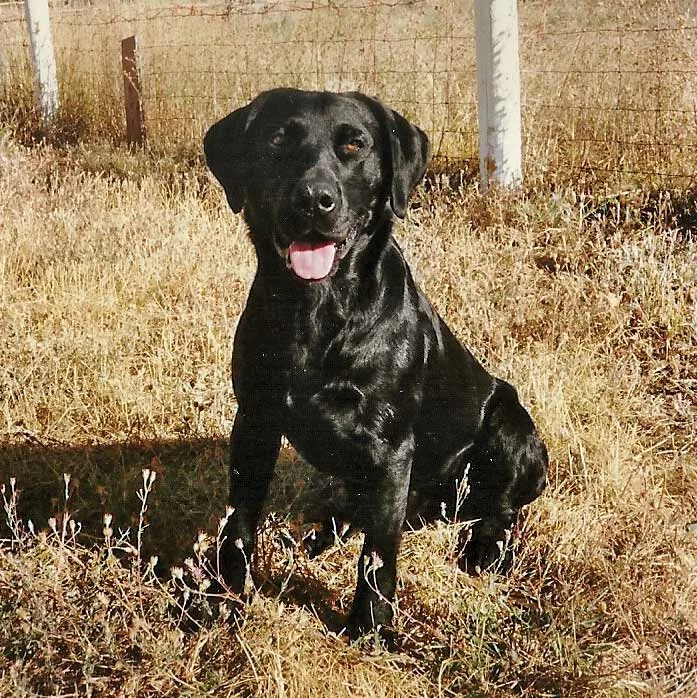

The author’s first hunting dog, Bear, takes a break during a bird hunt in Montana. Hal Herring

On weekends, we went east to hunt the prairies, lost for long hours in coulees. The sharptails, these ultimate natives, would bust from cover in heart-stopping flushes that ripped the fabric of that vast prairie silence. Often, I’d shoot and miss, but I connected enough to keep my dog’s faith in me strong, and keep him doing what he was, more than any dog I have owned or even known since, born for. At night, we’d make a camp somewhere on public land, and Bear would sleep curled against my sleeping bag, comatose, only to wake me later with his windmilling legs, closed-mouth barks and whines, and muscles tensing and untensing as he hunted, endlessly, in the country of dreams.

Looking back, I can only be so very grateful that we hunted so hard that fall of his third year. As I write this, memories tumble forth like photos stored in an old shoebox: Bear plunging through the ice on Freezeout Lake and fighting his way back to me, before I learned never to shoot ducks that would soar, dead, on a tailwind out over that beautiful death trap of a lake… December pheasants running in the wheat stubble, Bear closing on them, moving low to the ground, flushing them into the wind where they hung for a millisecond like zeppelins, then turned to rocket-ride that wind at velocities so great as to defy my conventional concepts of lead… Sharptails in a bog, grizzly scat bright orange with buffalo berry piled in the narrow passageways, and my dog, busting brush, the sound of birds flushing all around us, a moment of extreme luck as a small covey flew in a perfect crossing shot through an opening, the lead bird tumbling in a burst of feathers as I fired, the retrieve, a portrait for the ages—background of frost-reddened and -yellowed willows, dark ragged spruce against a flawless cold blue sky, the sharptail’s mahoganies and whites, the iridescent blue-black head and pale eyes of the greatest friend I had ever had…

Spring

In 1992, the Bitterroot Valley was changing all around us, the beginning of the land-development boom that would transmogrify the valley during our years there. Our house was at the end of the road, but an older gentleman, a retired excavator, had bought a small piece of land behind us and was planning to build his home there. Every morning, he drove slowly by our house, pulling a trailer with a backhoe on it. In the bed of his truck rode his Airedale, tall and proud. They were inseparable.

One cold day in March, I let Bear out while I put on my boots. We were going to go up Butterfly Creek in the Sapphires to get up to the snow line and see what we could find. I looked out the window and saw the excavator’s truck and trailer with the backhoe parked on the road in front of our house. The man, wearing a faded Carhartt jacket, was standing at our gate. I came out the front door.

“I ran over your dog,” he said.

I looked at him, looked around. “No,” I said. “Not my dog. He’s right around here somewhere. I just let him out.”

“No,” the man said. He had tears in his eyes. “It is your dog. I know him. I ran over him.”

Out in the road, Bear lay on his side. Not just dead, but absent. He had run out in the road—something that he’d never done before—and been barking at the Airedale. He’d gotten between the truck and the trailer, and the trailer with the backhoe had run clean over him.

“What can I do?” the man asked. “How can I help you?”

I said there was nothing to be done. The man must have thought that I was crazy, or the coldest person he’d ever met. The truth was I had no capacity to understand what was happening. I picked Bear up by the scruff of his neck, and he hung limply from my hand. I walked over to our fence and threw him over it into the yard.

“I don’t hold it against you,” I said. “But I have to go now.”

I went back into the silent house. My wife was at work at a plant nursery a few miles away. There were no cellphones. There was nothing to say, anyway. I’d messed up and gotten our dog killed. There was the dog bed my parents had bought Bear for Christmas. There were his toys, his training dummy, a cloth duck that he carried around, a rubber Kong ball. There was his food dish and water bowl.

For three years and three months, we had not been separated for more than a couple of weeks. I had started bird and waterfowl hunting with Bear. I had no idea what to do without him. I can’t remember the rest of that day. I don’t remember my wife coming home, or telling her what happened, or what we said. She was as close to Bear as I was.

It was cold. There was no hurry to bury him. I sat out in the late afternoon with his body. The days are so much longer in March, the daylight lingering, the winter so clearly over, a grim, almost unbearable contrast between the awakening earth, the light, and the inert black hide beside me, and I drank a pint of cheap whiskey, and for the first time, I cried.

My wife and I buried Bear the next morning at daybreak, on an island in the Bitterroot River. We left a sharptail wing to mark the spot, and we went home, to that silent house.

There were wonders still to come for us—a son and daughter, a small farm, new adventures, lives unfolding, expanding, other dogs and other hunts. But there was never another time like that one, never another dog like Bear, never that much freedom. Life goes on, they say. What they do not say—what is perhaps best left unsaid—is that so much of the best of it will only happen once. What I learned was to pay attention. Look around, feel this, love this, believe this. It is this way. And it will never be this way again.

This story originally appeared in Field & Stream Vol. 125, No. 2_._